Review: You’ll Laugh, You’ll Cry, You’ll Learn Absolutely Nothing: Taylor Mac and His History of Popular Music

Taylor Mac is not a teacher. If you’re interested in learning history—take a class. Read a book. Get sucked deep into a Wikipedia black hole and hang out for a while.

On Saturday, February 6th, actor, performance artist, and drag queen, Taylor Mac gave a performance of his A 24-Decade History of Popular Music that made me laugh, made me cry, and made me extremely uncomfortable. The only thing it didn’t do was teach me any history. Which, considering just how much it attempted to do—and successfully managed—was not such a big surprise.

Hosted by the University Musical Society, the show was part stand-up routine, part concert, part drag-show, and part performance art. I have no words for this sort of performance amalgamation, and so I was perfectly willing to accept Taylor Mac’s own description of the event as a “radical fairy realness ritual.”

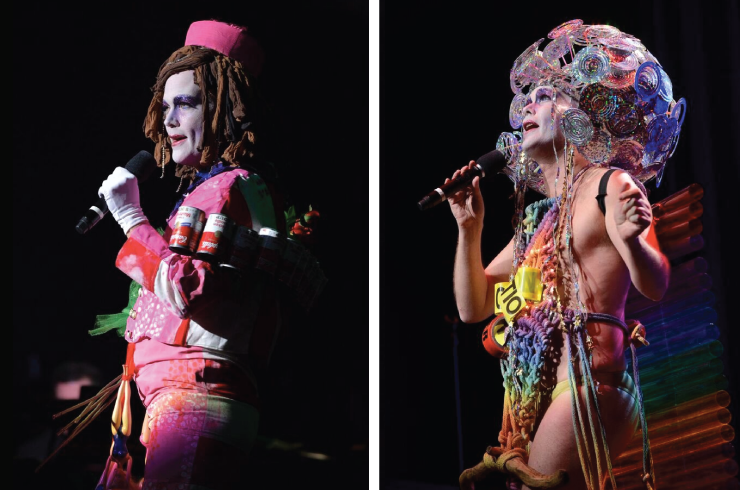

From the start, it was clear that the event would be unusual. Our host, Taylor Mac, came on stage in a hot pink skirt suit spray painted with an American flag on the back, a sash made of soup cans, and a jaunty little hat. Behind him on stage sat a band of seven musicians—a pianist, a bassist, a drummer, a guitarist, a guy who seemed to be playing a different instrument every time I looked at him (saxophone, trumpet, flute, possibly the flugelhorn), and finally, two exceptionally powerful back-up singers.

Mac began the show by explaining the bare bones of his musical project—each hour of the three-hour performance would be dedicated to a different ten-year period: 1956-1966, 1966-1976, and 1976-1986. Each decade came complete with its own costume, eight or nine songs from the time, and a central historic theme. This performance was just a fraction of a much larger endeavor Mac has planned for a later date, a 24-hour performance with an hour for every decade from America’s inception in 1776 all the way up to the glorious pop-fest that is the year 2016. Mac explained the idea that he would be on stage for a full 24 hours, singing and entertaining non-stop without food, bathroom, or sleep breaks, with the casual air of someone who is either very confident or incredibly irresponsible. Possibly both.

Probably both.

The first decade of our less-ambitious 3-hour show, ’56-’66, focused on aspects of the Civil Rights movement, or, as Mac puts it, “Songs Popular in the Bayard Rustin Planning Room.”

It kicked off with a slow and sultry rendition of Jay Hawkins’s “I Put A Spell On You.” By itself this would have been excellent entertainment—Mac’s stellar flair for theatrics is matched by his smooth, powerful voice. But just in case the audience had started to settle into the comfortable idea that they were at some tedious concert-meets-comedy-meets-drag-show, Mac introduced a new and terrifying element: audience participation.

After a very brief introduction of the racially tense atmosphere pervading the late ‘50s, Mac asked all of the straight, white people in the audience to stand up and slow-motion run to the sides of the room, simulating white flight.

“I understand that there won’t be a lot of room for you over there,” Mac said to the amazingly willing audience as they wiggled and stepped over each other to get to the sides of the room, “But I really want you to get the feel of the suburbs. I want you to be so close together that there’s a straight, white person on top of you even when you really don’t want a straight, white person on top of you.”

By the end of the song, I wasn’t sure if I was laughing, crying, or hyperventilating. If you’ve never seen a hundred people of all ages, including senior citizens, slow-motion run to the sides of a room and pack in like sardines, I highly recommend it.

With all of the elements fully introduced, the show really got under way. The ‘56-‘66 hour contained a bit of background on race issues and centered its attention on the March on Washington, though unfortunately most of the story that Mac told focused on the imagery of getting on a bus to go to the March. It involved an awful lot of audience playacting of getting to the bus/being on a bus/singing on a bus, without much actual information on the March itself.

Despite the fact that Mac didn’t tell much of a story, the music certainly did. The songs were well-chosen, a combination of Civil Rights anthems like The Staple Singers’ “Freedom Highway” and Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” and chart-toppers like The Supremes’ “You Keep Me Hangin' On” and Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.” The songs that came with their own clear message, such as the impossible-to-misinterpret “Mississippi Goddam” were as powerful as you might expect. But even the popular hits, thrown in front of the backdrop of the 1950s and forced into context gave songs like Simone’s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” deeper meaning and even greater muscle.

I’ll admit it—the ‘56-‘66 decade was definitely my jam. But the following decades carried the same sort of structure and a lot of the same impressive weight.

Curtis Mayfield’s "Move On Up" transitioned us into the 1966-1976 decade, as Mac stripped down to a tiny yellow Speedo on stage, then disappeared behind the curtain and remerged in an outfit made up of so many different things that I honestly couldn’t tell if it was a dress, a jumpsuit, or if he’d tripped and fallen into a scrap box on his way back to center stage. The whole ensemble was tied together by a rainbow cape made of clear plastic tubes and a glittery silver headdress. This era had its eye trained on the beginnings of the gay liberation movement and the Stonewall riots of 1969. Songs included Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run,” Patti Smith's "Birdland," and The Rolling Stones' "Gimme Shelter."

The 1976-1986 decade focused on the idea of the '70s and '80s club scene and their infamous "back rooms." This aspect of history seemed like an odd choice until I realized that these "back rooms " were a prevalent part of Mac's own experience as he came up in the club scene. Dressed in a bright silver jumpsuit with a ruffled purple shawl and a shiny purple mohawk, Mac told his most personal (and most graphic) stories during this era in between Laura Branigan's "Gloria," David Bowie's "Heroes," and Prince's "Purple Rain."

The gaps between each song were filled with comic stories, musings, and, of course, the obligatory ridiculous activities that come with performance art. During the 1956-1966 portion of the show, audience members were asked to dance, march, engage in some pretty exaggerated crying, and, finally, to email Rick Snyder.

Sometime around the 1970s, we were handed ping-pong balls to throw at Mac as he ran through the aisles in his rainbow-tube cape and yellow Speedo. As we moved into the late '70s part of the show, Mac pulled an older gentleman up on stage and sang him a love ballad, while the pianist groped the man’s leg.

In the '80s, he had an entire row of the upper balcony come downstairs, go behind the curtain onstage, and emerge in ridiculous wigs, boas, and glasses and dance through the aisles. Each activity was a bit more unbelievable than the last, finally culminating in a college-aged boy standing patiently still while Taylor Mac kissed him and rubbed glitter lipstick all over his face. Permission was not asked, just a perfunctory, “You’re over 18, right?”

It was wonderfully weird, and, while the entire thing carried the feel of a glittery game of Russian roulette as we waited to see who would be Mac’s next participation victim, it also succeeded in doing exactly what Mac had told us it would—creating a shared experience for the audience. The audience was incredibly good-natured, dancing when asked, moving when asked, and making sure to applaud loudly and sincerely for anyone who was a good enough sport to obey instructions like, “go stand on stage, but don’t smile and don’t dance” or “lay down on the floor and let these five strangers carry you out of the room.”

From all this highly entertaining madness, I only came away with one critique. As a person who would have loved all the elements of this show even if they were completely separate and not one giant, Katamari Damacy-style ball-of-everything, I was absolutely enchanted by this performance, so much so that I didn’t even resent Mac for keeping me up past my 8 pm bedtime. Give me comedy, music, or drag any time of day and I’m game. But I was also interested in the promise of some really good history-nerd satisfaction, and so I was a bit let down by the minimal emphasis on the actual history.

While Mac did occasionally address the lack of historical fact—“If you want to know more about the March [on Washington…Google it. What about this outfit says anything more than Wikipedia?”—I felt like it was such a shame to dismiss the history so casually because of how much it could have brought to the show. Even the barest skeleton of historical facts would have ramped up the storytelling element and could have made this fun and flighty show a little bit stronger and a lot more engrossing, particularly in the gaps between musical numbers.

But considering how much it did do right, I really can’t fault it for the one thing it didn’t completely ace. The show managed to be a masterful musical performance, an entertaining drag show, and a surprisingly fun communal audience experience, so really, who cares if he didn't include a history lesson? It was still a performance I’m not likely to forget. At least, not in this decade.

Nicole Williams is a Production Librarian at the Ann Arbor District Library and, despite this positive experience, still thinks audience participation is the worst.