Personal Investment: Blind Liars Explore Self-Worth and Authenticity on “The Ringer” Album

For Blind Liars, a debut album provides a vulnerable outlet for understanding one’s self-worth.

The Ypsilanti indie-rock quartet unearths deep emotions from the human psyche—including shame, disappointment, and loneliness—to reveal an authentic sense of self on The Ringer.

“A decent amount of what we have on the album deals with failure and loss and picking yourself up from it,” said Schala Walls, one of Blind Liars’ lead vocalists and multi-instrumentalists. “The very act of writing this music was kind of an investment in my self-worth, so all of the songs kind of reflect that.”

Alongside bandmates Jon Root (lead vocals, songwriting, keys, guitar, bass) and Eric Bates (drums, bass, guitar), Walls channels personal experiences of social alienation due to neurodivergence and queerness across eight cerebral tracks. (Bassist Mari Neckar joined after the album was recorded.)

The Ringer features intimate ballads, howling sing-alongs, and emotional tales steeped in ‘60s prog-rock, shoegaze, and a kitchen sink-full of other influences.

We recently spoke to Blind Liars about the band’s formation, its newest member, the album’s theme and sound, the writing and recording process, upcoming album release shows, and future plans.

"Lean In" and Listen: Ness Lake's Chandler Lach on bedroom emo, prolific songwriting, and digicore

Chandler Lach explores raw emotions and deep themes of love and heartache on his new album as Ness Lake, I Lean in to Hear You Sing. Released in May as the follow-up to Ness Lake's 2022 record, Yard Sale, the new album displays Lach's evolution as a songwriter and a more expansive sound as an arranger, lacing his indie-folk pop with electronics.

The Ypsilanti-based Lach is turning Ness Lake into a full band with Marco Aziel (bass), Jack Gaskill (drums), and Tanner J. Ellis (guitar), and the quartet is woodshedding this summer to prepare for fall concerts.

I talked with Lach about his beginnings as an artist, his writing process, what he's been listening to, and I Lean in to Hear You Sing.

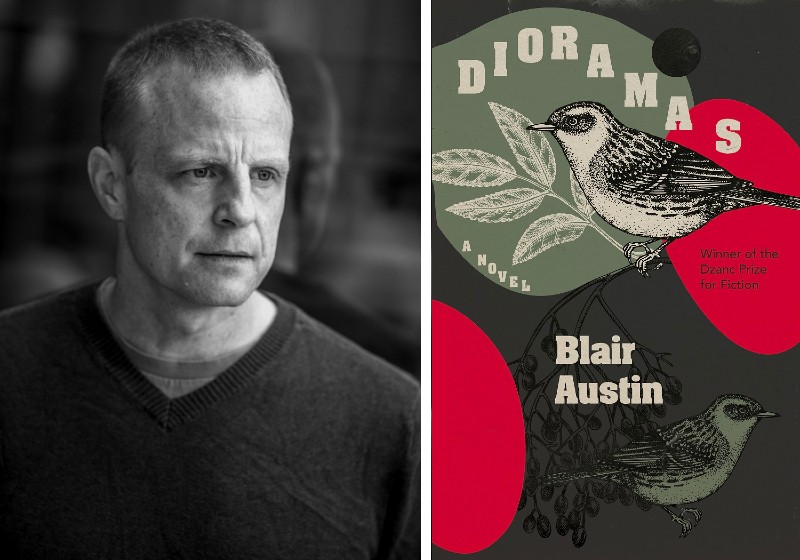

Lifelike Living: Blair Austin's inventive new book, "Dioramas," defies easy categorization

Blair Austin's Dioramas, which won the Dzanc Books Prize for Fiction, is described by the publisher as “part essay, part prose poem, part travel narrative.”

The author—an Ann Arbor native and University of Michigan MFA alum—describes dioramas to “view” through the eyes of the main character, Wiggins, whose stream-of-consciousness narration means that the reader must piece his world together as the book progresses.

Austin creates a semblance of beauty in the slow-growing shock of what is contained in the dioramas' preserved scenes.

Wiggins, a lecturer, is a scholar of dioramas and builds them, too, even in retirement. He studies the works of experts Michaux and Goll, both of whom made dioramas and contributed their theories about the art form to the field. Regarding Michaux, Wiggins reveals:

Friday Five: Miller Twins, Adam J. Snyder, Studio Lounge, Vitamin TI, Dykechow, Bubu

Friday Five highlights music by Washtenaw County-associated artists and labels.

This week features modern classical / exploratory jazz / power pop by Benjamin and Laurence Miller, folk by Adam J. Snyder, quirky pop by Studio Lounge, retrowave by Dillan Pribak, and dance mixes by Vitamin TI, Dykechow, Bubu for the ongoing Immaculate Conception and MEMCO series.

"Ghost" Stories: Jonathan Edwards explores a sparser sound on his lyrical new solo album

Jonathan Edwards recorded, produced, and performed the 13 songs on Wild Ghosts almost entirely by himself, playing everything from bass and drums to synthesizers and Wurlitzer organ.

But he could have just as easily performed the beautiful songs on Wild Ghost solely with his guitar, the instrument at the heart of the album, with Edwards displaying excellent fingerstyle playing throughout the record.

"Wild Ghosts is definitely more of a singer-songwriter album than anything I have done in the past and is something I have wanted to do for a long time," said Edwards, who studied music at Indiana University and Eastern Michigan. “Most of the songs on Wild Ghosts can be distilled down to more traditional folk tune-type influences, although there are still some more elaborate and dense arrangements with songs like ‘Paper Birds’ and ‘Mask of Bees.' Simplification is an art I am still learning."

I talked with Edwards about his musical upbringing, his influences, his writing process, Wild Ghosts, and more.

My Generation: Social Meteor Shares Everyday Struggles of Gen Z and Millennials on Self-Titled Debut Album

Social Meteor didn’t expect its debut album would speak for a generation—or two.

It started as a creative outlet for documenting each member’s challenges but soon evolved into a collective voice for sharing Gen Z and Millennial struggles.

“All the songs are a reflection of what our lives have been like and the struggles that we go through on a day-to-day basis living in 2023 and the past few years,” said vocalist-keyboardist Jordan Compton about the Ypsilanti indie-rock band’s new self-titled album.

“It’s honest because we didn’t intend to make some grand scheme, and we didn’t know what the theme of this album was gonna be when we picked the songs to go with it. It formed over time and reflects what it’s like to live in modern America as a younger person.”

Those reflections not only come from Compton, but also from his three Social Meteor bandmates: Paul Robison (drums, vocals), Brad Birkle (guitar, vocals), and Patrick Frawley (bass, vocals). Together, they explore relationships, losses, and lessons alongside complex emotions.

“They’re like journal entries, and it’s more of a personal approach. When we are trying to write songs, everyone writes them a little differently,” said Robison, who co-formed the group in 2019 and co-derived the band’s name from a wordplay on the term “social media.”

“The nice part about us is that we can all write songs … and something I’ve taken from them is: ‘Don’t try to pretend and be like somebody else. You can take information in from other people, but don’t fake it; try to make it real.’”

Sing Us a Song: The piano men and women of "Duelers" star in a new Michigan-produced film with deep local connections

Duelers Piano Bar is the home of five young musicians who trade keyboard licks and share solace, shots, and sounds on a nightly basis. But the venue that offers them a routine and respite from problems is about to be sold by a money-hungry owner, which will turn their lives upside down.

This is the plot of Duelers, a new movie made by a group of multi-talented Michigan creatives. Writer/composer/co-star Drew De Four, producer / cinematographer Danny Mooney, and their cast of real-life performers straddle the line between a concert film and backstage drama. The film was shot at the now-closed J.D.'s Key Club piano bar in Pontiac, Michigan, taking 12 days over two weeks.

Like his co-stars, De Four is a real dueling pianist, and his talents have taken him around the globe. During shooting, he lived with the actors who play Tyler (Tom McGovern), Jane (Elisa Carlson), Skip (Danny Korzelius), and Bethany (Shelby Winfrey), the multi-talented musicians who share the stage nightly with Drew (De Four) at the fictional Duelers Piano Bar.

De Four, 40, has been playing in piano bars since he was 19. He was a student at Eastern Michigan University when he saw an ad for Pub 13, a dueling pianos bar in Ypsilanti.

"I took five years of piano lessons from ages 7 to 12," De Four says. "From 12 to 18, I taught myself piano, guitar, bass, mandolin—a little bit of drums. When I was 19 I went to Eastern for a year to study piano, and my professor told me I should not be studying classical piano because when I came back from the piano bars asking, 'How do I do stride piano?' He said, 'You could teach me. You seem to know exactly what you want to do. We're studying Rachmaninoff and Liszt: That's not what you're meant for.'"

In Summary: Folk-Rocker Jeff Karoub Contemplates Life’s High Points on “Between the Commas” Album

During his time at The Associated Press in Detroit, Jeff Karoub wrote obituaries about Motown legends, baseball coaches, and other people of note.

Those obituaries recounted life accomplishments and caused the Dearborn singer-songwriter to ponder how he’d best summarize his own life.

“At the AP, we called that ‘between the commas’—the high points of someone’s life. You know, the stuff you might be remembered for—good and bad,” said Karoub, who now works as a senior public relations representative at the University of Michigan.

“Imagine that you’re reading your obituary: What would you like it to say? What’s in there? Pack it in; you don’t have a chance afterward. You only have a chance now to start putting in the good stuff.”

Karoub advocates bringing that “good stuff” to light on the title track from his latest folk-rock album, Between the Commas. Serene electric guitar, acoustic guitar, bass, keys, and drums echo that sentiment as he sings, “What I offer is just one small thing / Imagine your obituary / Think of what you’d like to say / Something more than ordinary.”

“It’s not that I’m necessarily demanding that you all come gather around and listen to my wisdom; it was as much wisdom to myself,” Karoub said.

“The ideas were coming to me before my mom died [in late 2021]; she wasn’t the inspiration, but she was a catalyst. That makes it more pressing when you lose one of your parents or someone very close to you.”

Friday Five: Eve Machines, Juliet Freedman, NewBassoon Institute, The Regenerate! Orchestra, Pepperoni Wilson

Friday Five highlights music by Washtenaw County-associated artists and labels.

This week features indie-folktronica by Eve Machines, folk-pop by Juliet Freedman featuring Ben Wood, and site-specific performances and/or compositions by the NewBassoon Institute, Pepperoni Wilson, and The Regenerate! Orchestra.

Heading East: Grand Rapids Outlaw-Country Band The Bootstrap Boys Perform July 22 at Saline's Acoustic Routes Concert Series

The Bootstrap Boys are driving their outlaw-country anthems eastward to Saline later this month.

The Grand Rapids quartet plans to unpack rowdy tales from their five-album catalog during a July 22 Acoustic Routes show at Stony Lake Brewing Co.

The show serves as The Bootstrap Boys’ debut appearance at the decade-old Saline concert series. It’s also the only Washtenaw County stop on a current summer tour in support of their latest album, Hungry & Sober.

Throughout the album, vocalist-songwriter Jake Stilson (Big Jake Bootstrap), guitarist Nick Alexander (Nicky Bootstrap), bassist Jonny Bruha (Jonny “Bubba” Bootstrap), and drummer Jeff Knol (Jeff Bootstrap), share “cheerily nihilistic road tunes” and “sincere ruminations on family and queer identity” alongside hard-hitting, country-rock instrumentation.

“This album has more honest poetry to accompany the storytelling that’s always a part of my work,” notes Stilson on the band’s website, which credits Willie Nelson, Waylon Jennings, and Bob Wills among the band’s biggest influences. “I edited myself a lot less.”