The Share Zone: Ann Arbor Art Center launches multimedia exhibit "Sharing Space," the first show in its new building

What is space?

Is it the physical area around you?

Is it your mental perceptions of isolation versus intimacy, distance versus closeness? Finding your place in a crowd versus being alone with your thoughts?

Is space the place where we should launch Elon Musk on a Major Tom-like mission to Mars?

The artists in Sharing Space, a new multimedia exhibit at the Ann Arbor Art Gallery (A2AC), ask variations of these questions—except the one about an Elonaut floating around a tin can, that's all on me.

Sharing Space is A2AC's inaugural full exhibit in its newly increased footprint, which came about because the venerable institution bought and expanded into the building next door, reconfiguring nearly everything throughout the three floors of both structures. (MLive did a nice story on the renovation.)

The name Sharing Space is also a nod to a driving idea behind A2AC's newly configured galleries and workspaces. While A2AC has always been about sharing space with the community—the exhibits are free; the paid art classes welcoming to newcomers—its commitment to expanding deeper into the general public is front and center now.

The pandemic has also made us reconsider how and when we share spaces with others. Even though covid variants are still raging everywhere, the world has made the conscious decision to open up again, which means whether or not we're emotionally or physically ready, we have to figure out how to share spaces once again.

"I wanted our first exhibition to be something that spoke to our own process of coming back into the public emerging with our new space," said Interim Gallery Director Ashley Miller.

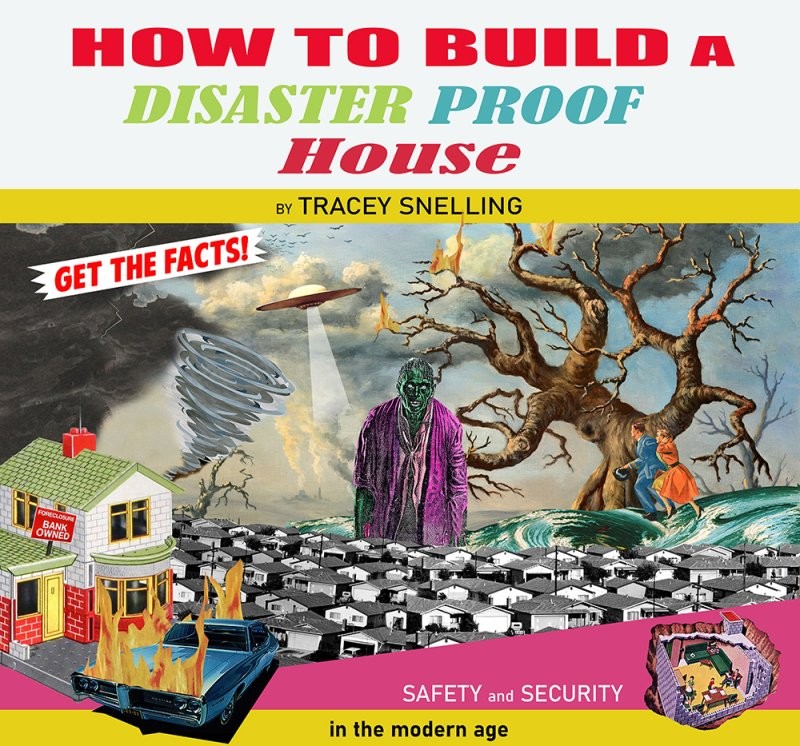

Tracey Snelling's "How to Build a Disaster Proof House" constructions contemplate displacement and disenfranchisement

A vibrant installation at LSA’s Institute for the Humanities Gallery asks viewers to contemplate the utility (or lack thereof) of building a “disaster proof house.”

Tracey Snelling, the current Roman Witt Artist in Residence at the gallery, returns to LSA after previously exhibiting Here and There in 2017, which addressed “challenges of economic inequities, racial biases, and imposed class divisions that often limit the options available to so many people.” Her new exhibit, How to Build a Disaster Proof House, curated by LSA's Amanda Krugliak, “contemplates the uncertainty, displacement, and disenfranchisement that frames the present day” and asks, “How do we find a safe place, protected from bad weather and circumstance, in an era of floods, fires, violence, abuse and pandemics?”

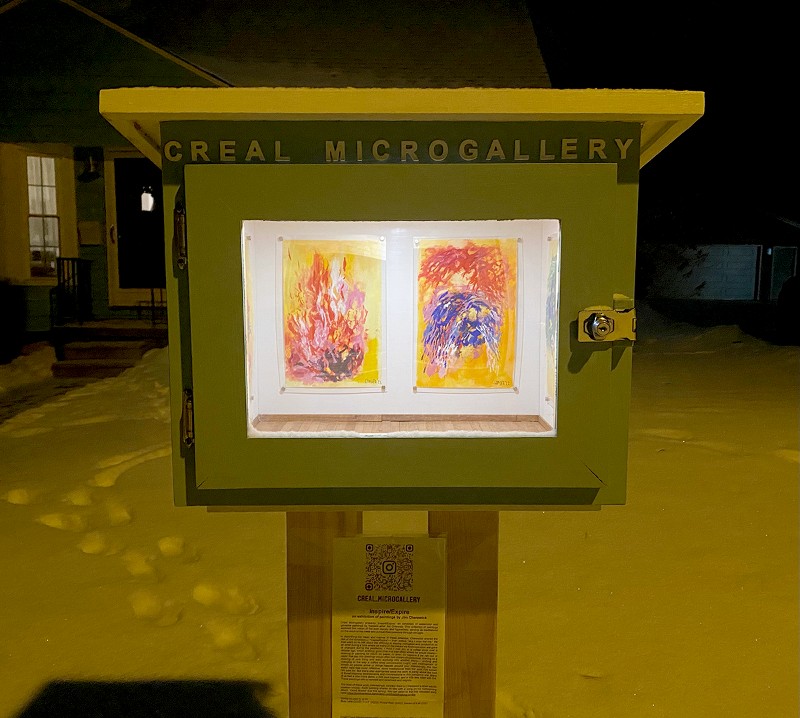

Ann Arbor's Creal Microgallery offers tiny exhibitions for unsuspecting pedestrians

The first reaction a pedestrian might have upon encountering the Creal Microgallery in suburban Ann Arbor might be amusement. This tiny, breadbox-sized art space on Creal Crescent, not far from the North Maple Road and Miller Avenue intersection, resembles one of those little free libraries often found on residential streets. It provides curbside delivery of fine art to passers-by from dawn to 11 pm daily. This may not be a grand structure like the elegant Stettheimer dollhouse in the Museum of the City of New York, with its tiny masterpieces by Alexander Archipenko, Gaston Lachaise, and Marcel Duchamp, but it’s no joke either.

The microgallery’s founder and curator, Joe Levickas, was inspired to start the project by dislocations in his life during the COVID-19 pandemic. He describes bringing up his idea for the gallery with his wife. “What if we put up a gallery in our front yard?” A real team player, she replied, “You should totally do it.” He acquired a 16”x10”x12” box with a glass front, painted it robin’s egg blue to match his house, and the rest is (art) history.

Mary Sibande's "Sophie/Elsie" sculpture anchors UMMA's African art gallery

Sophie/Elsie is a striking sculptural figure, vibrant and visible from a distance, a colorful, bright beacon in the newly expanded and reopened African galleries at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

Johannesburg-based artist Mary Sibande’s fiberglass sculpture, created in 2009, and initially on display during UMMA’s closure, is now permanently installed. In the early days of the museum’s closure, Sophie/Elsie was visible from outside the galleries—then, construction came, and she was no longer visible from outside.

But Sophie/Elsie is once again on display in the reimagined space of UMMA’s African galleries. Along with works by Jon Onye Lockard, Shani Peters, Jacob Lawrence, and many more, Sibande’s sculpture brings new life to the gallery space as part of the ongoing initiative We Write to You About Africa, in which “contemporary African artists, scholars, and curators will be asked to write about their work on postcards, in their first language, and mail them to UMMA where they will be displayed alongside their works.”

The reinstallation—including a gallery extension—is now open to visitors in the Robert and Lillian Montalto Bohlen Gallery of African art and Alfred A Taubman Gallery II.

AADL 2021 Staff Picks: Homepage

This is the fifth year we've compiled Ann Arbor District Library staff picks, featuring tons of recommendations for books, films, TV shows, video games, websites, apps, and more.

The picks are always an epic compilation of good taste, and last year's post was more than 35,000 words—incinerating phone data plans and overheating computers as the massive page loaded.

In a sincere effort to keep your electronics from catching fire, we've split up the hundreds of selections into four categories:

➥ AADL 2021 Staff Picks: Words

➥ AADL 2021 Staff Picks: Screens

➥ AADL 2021 Staff Picks: Audio

➥ AADL 2021 Staff Picks: Pulp Life

And since we've saved your phones and laptops from the flames, tell us what you enjoyed this past year in the comments section below—doesn't need to be something that came out in 2021, just some kind of art, culture, or entertainment that you experienced over the prior 12 months.

Ann Arbor Gallery Crawl: Catching up with recent exhibits and new art spaces

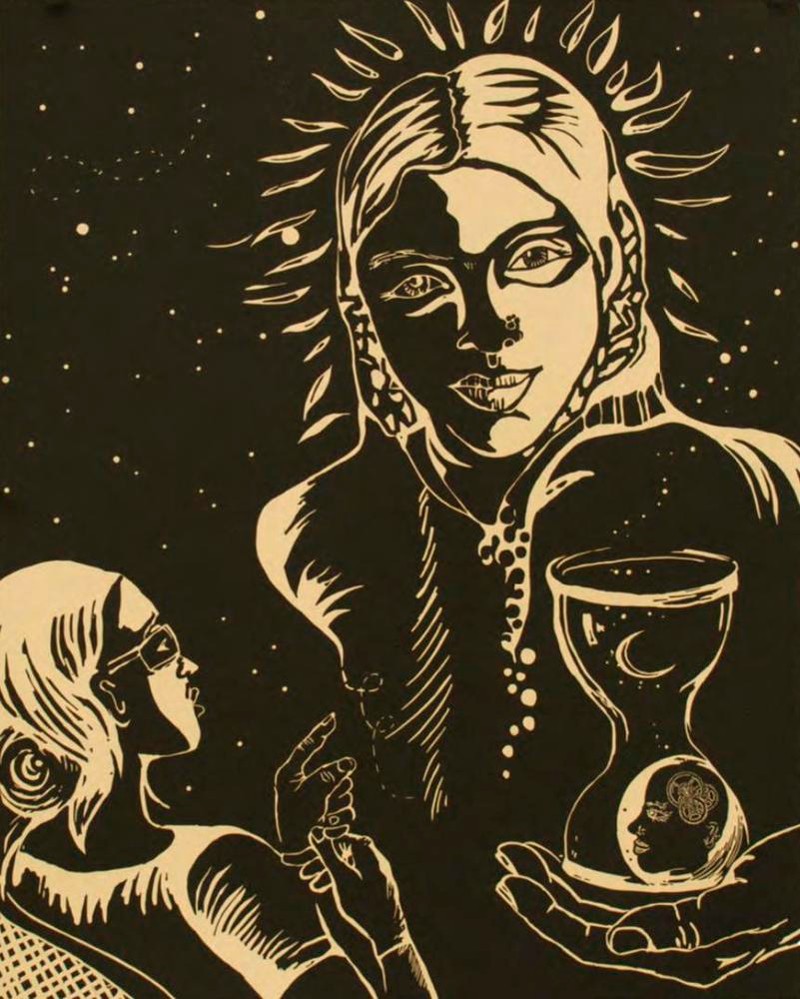

Double Goddess: A Sighting in the Abyss by Ayana V. Jackson at A2AC Gallery. Photo by K.A. Letts.

COVID-19 has wrecked plans and canceled events for nearly two years (and counting). It has sabotaged the momentum and slashed the incomes of Ann Arbor’s small community of visual artists and galleries, leaving a cultural landscape greatly altered in ways large and small.

But the creatives here are nothing if not resourceful and, well, creative.

My recent tour of the art spaces and non-profits in Ann Arbor and environs left me encouraged—and impressed—by the resilience of the city’s art community. Here are some of the changes I came across while reintroducing myself to the local art scene in early December 2021:

Stamps Gallery's "Envision: The Michigan Artist Initiative" celebrates creators who are inspiring the next generation

Based on my direction of approach to the University of Michigan's Stamps Gallery, I didn’t see Michael Dixon’s large-scale sculptural alligator head with one sharp, gold tooth before entering—though it's visible in the gallery’s large front windows.

Inside the sculpture’s large open jaw, children’s toys rest as if inside a toy box. Among them, a selection of brightly colored balls, dolls, and books we might recognize from a modern store, but also amidst the display are racist toys such as a mammy doll, which remind viewers that these harmful toys are still collected and sold, holding a space in contemporary American culture that often escapes criticism.

This idea is further enforced by the inclusion of problematic Dr. Suess books, which became a topic of national conversation this past March.

Dixon is among five artists represented in Envision: The Michigan Artist Initiative, a new program focused on promoting the careers of Michigan-based artists.

This awards initiative “recognizes the creativity, rigor, and innovation of Michigan-based artists and collaboratives—and honors their role in inspiring the next generations of artists in our state.”

Shizu Saldamando’s exhibit "When This Is All Over/ Cuando Esto Termine" captures the anxiety and depression of pandemic art

Over the past year, I've come across artwork that exemplifies what I would describe as a new genre: pandemic art. A significant number of emerging creatives are making work that displays a high level of anxiety and depression brought on by their isolation and a well-founded sense that their lives, plans, and ambitions have been put on hold. Shizu Saldamando’s solo exhibition When This Is All Over / Cuando Esto Termine, on view at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery until December 10 and curated by Amanda Krugliak, is yet another example of this distressed trend.

It's clear that the COVID-19 pandemic has been particularly difficult for early career professional artists like Los Angeles painter Shizu Saldamano. Her diverse circle of friends, many of them Latinx and/or LGBTQ, represent a cross-section of young creatives eking out their existence in L.A.’s gig economy. Right now, they are pursuing their avocations—as musicians, artists, DJs, and the like—in the midst of economic and medical uncertainty.

They are the subjects of Saldamando’s large portraits.

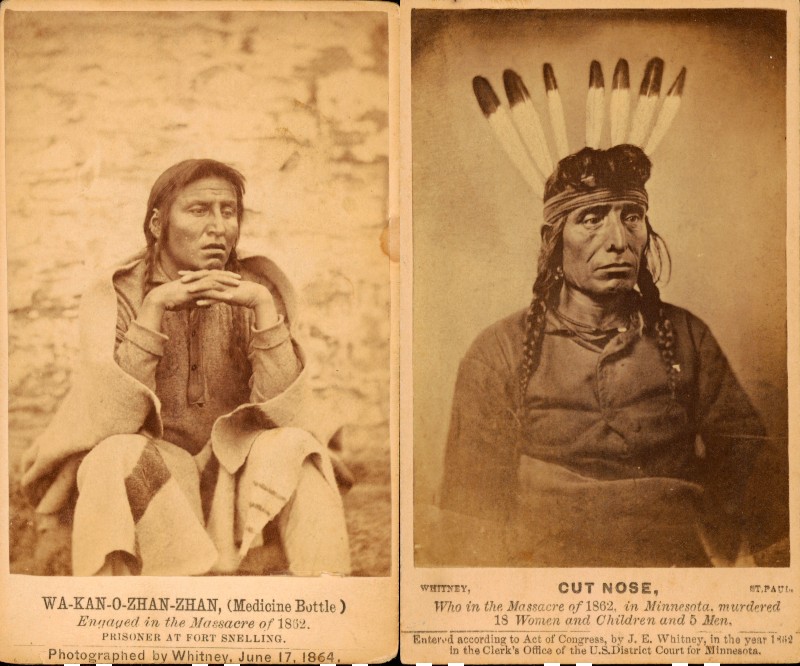

“No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography at U-M's Clements Library

Joel E. Whitney

Carte de visite, 1864

Wa-Kan-O-Zhan-Zhan, or Medicine Bottle, was a Sioux wicasa wakan, or holy man, who stepped away from that role to defend the Dakota way of life in the rebellions. After the uprising, Congress called for the removal of all Sioux from Minnesota, leading Medicine Bottle to flee to Canada. Two years later, he was found, drugged, and brought as a prisoner to Fort Snelling, Minnesota, where he was tried for his participation in the 1862 uprisings. He was executed three years after the initial trial. This photo was taken shortly before his death.

Joel E. Whitney

Carte de visite, 1862

Marpoya Okinajin (pronounced: Mar-piy-a O-kin-a-jin) was also known as Cut Nose or He Who Stands in the Clouds. His vibrant life was filled with stories of hunting, fighting, and womanizing. Cut Nose’s distinctive name is credited to John Other Day, who allegedly bit off a chunk of his nose during a fight. During the Dakota War, Cut Nose fought to restore Santee Dakota sovereignty in Minnesota and is remembered for his leadership and brutality in the uprisings at Fort Ridgely, Minnesota. He was ultimately executed for his violence against settlers on December 26, 1862. After his death, William Mayo, a founder of the Mayo Clinic, exhumed Cut Nose’s remains to use for science experiments, keeping his bones for over a century and a half. The eagle feathers appearing in this photo were likely retouched into the photo after it was taken.

This review was originally published December 3, 2020; after the jump, we've included a video interview with the curators published on AADL.tv on November 15, 2021 as part of 30 Days of National Native American Heritage Month.

As I look out over a pond that's rippling gently from snowfall, the pine trees and fields covered in white, I'm writing this post in my Christmas-light-bright house, which rests on Bodéwadmiké (Potawatomi) land ceded in a coercive treaty.

A version of the above sentence is also what begins “No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography, an online exhibition produced by two University of Michigan students with Native American ancestry for the William L. Clements Library. Lindsey Willow Smith (undergraduate, History and Museum Studies; member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians) and Veronica Cook Williamson (Ph.D. candidate, Germanic Languages and Literatures and Museum Studies; Choctaw ancestry, citizen of the Chickasaw Nation) used materials in the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography to explore ideas of consent, agency, and representation.

At Odds: "Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection" imagines a place where LGBTQ+ art can thrive

Art is often intentionally ambiguous, asking viewers to create meaning and metaphorically fill in the blanks with their interpretations.

So, then, what is queer art anyway?

(Spoiler! This exhibit will not define it for you.)

In Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection, compiled by doctoral candidate and 2019-2020 Irving Stenn Jr. curatorial fellow Sean Kramer, there is no essential “queerness” harnessed and presented in a neat package. Instead, the exhibit is framed by the words of activist, author, and professor bell hooks: “Queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

The University of Michigan Museum of Art is now fully open to the public, but Oh, Honey—UMMA's first self-described queer exhibit—went live virtually in fall 2020. Even so, the online exhibit doesn't have the same impact due to Kramer’s curatorial approach: the physicality and placement of the works affect their readings.

In this vein, it is important to note that each artwork was created by a different artist with a unique relationship to the external world; not everybody defines queerness or “queer art” in the same way.