Review: UMS presents 'Dorrance Dance' at the Power Center

If you’re going to see Dorrance Dance, and you should (there’s one more show, tonight at the Power Center), go with your eyes peeled, your ears pricked, and your antennae waving. Sit up, pay attention -- you’re going to space out. With the first piece on the program, excerpts from SOUNDspace, you will have to take in the fact that all the music -- all the different tones and volumes and counterpoint rhythms -- you hear is generated by dancers’ feet. Don’t stop watching, though, because the scene before you will shift pretty swiftly.

Michelle Dorrance, the MacArthur Genius (2015) choreographer who masterminds the show, gives you a quick primer, an introduction to her multi-sensory world. Early on, you see four dancers lit from the waist down, compelling your focus to the lower body. Those legs and feet enunciate slowly at first -- see how a different touch by a different part of the foot results in a different sound, and see how those sounds combine. Oh, and don’t fail to notice the catchy angular patterns that the eight legs make, rotating in and out to create a kaleidoscope of bending knees and flexing ankles. Got it? Great, because Dorrance is moving on, expanding the vocabulary. She and Elizabeth Burke, with upper bodies still in semi-darkness, are trading steps, and although the angles are still there, more complicated rhythms are flying. This is a good time to mention that every single dancer you see is a hotshot; Dorrance repeatedly pulls off a move that I can’t even compute -- what the hell are her feet doing?

And that’s it; your education in this medium is over and all you can do is go along for the ride. All the lights are up, and Dorrance does a solo that both slides and taps. Dancers come and go in pairs and quartets, eventually circling around Warren Craft. As he tips, twists, and topples, the others accompany him with a snuffly, sandy sound, perforated by silence and snaps. By now you are fluent, comfortable in this world. Good, because it’s about to change: four dancers appear on wood platforms that have a furrow-patterned metal panel along one side, like a washboard. The possibilities for feet-generated sound have just multiplied, and it’s fun to watch and listen to the dancers play this new surface with their heels. Enjoy the super-satisfying simplicity of each dancer -- quickly, one after another -- dragging a foot along the washboard and as the foot releases, spinning: kkkshrwih spin, kkkshrwih spin, down the line.

Here you might become aware that you are watching only an excerpt of the full-length SOUNDspace. Just as the dancers begin, STOMP-like, to play with the potential that different objects have for making sound -- still on the washboard platforms, they suddenly have metal chains that, when lowered or dropped, add a distinct sound to the percussive mix -- the dance is over.

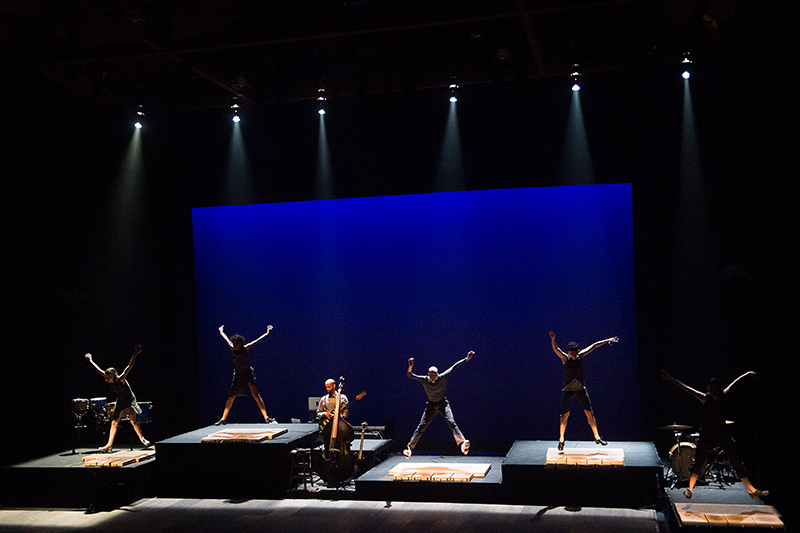

It’s okay. Stretch your legs and reset your head, because as lush and variegated as the sensory world of SOUNDspace was, it seems practically flat in comparison to the explosion that is Act II, ETM: Double Down (again, excerpted here from a longer work). Whereas in SOUNDspace you have only (“only”!) the music generated by feet talking to the floor, in ETM, the floor finds its voice. On wired platforms designed by Nicholas Van Young, every step not only makes the expected tap sound but also triggers an electronic tone. Now there are musicians on stage too -- Donovan Dorrance, Aaron Marcellus, and Gregory Richardson -- their live performance instantaneously recorded and played back so that they can accompany themselves. Richardson plucks a simple theme on his stand-up bass, then impishly stands by as the theme continues without him touching his instrument. He layers on bowed tracks, then switches to electric guitar. Vocalist Marcellus lets loose with a stream of golden tones, these likewise immediately re-played and altered by a device he holds in his hand.

You get the idea: the sonic landscape has exploded. In the same way, the movement goes far beyond its Act I parameters. SOUNDspace’s movement vocabulary -- with the exception of Craft’s rubbery, off-kilter solo -- stayed largely in the realm of familiar tap-dancing. Dancers were upright with their torsos inclined a bit forward, arms mostly a functional, swinging counterbalance to the complicated activity below. In ETM, upper bodies become more eloquent, and the more pedestrian, vertical stance cedes some of its default status. This isn’t always successful, as when Dorrance stands slumped and alone; she seems contrived or affected, like a caricature of despondency. More often, though, the expanded physicality delights. Dorrance shares a duet with Craft in which they lean into each other, barely holding each other up as their feet get away from them on some runaway train.

Matthew “Mega Watts” West shows up, and at first he seems gratuitous -- why is this man in sneakers rather than tap shoes executing showy hip hop and b-boy moves? Sure, these forms share a common Africanist lineage with tap, but you might think he looks out of place. You’ll get over it; he is the harbinger of a broader and richer movement palette.

There is a nearly perfect duet for Byron Tittle and Leonardo Sandoval, poignant in an unexpected 3/4 time. One leans, the other holds him up, slides him across the floor. They are in sync, and then just a little out, like windshield wipers gone awry. Sandoval stands and watches Tittle dance, but when Sandoval dances, Tittle faces away -- it’s so apparent, though, that he’s listening intently to Sandoval. Somehow, it’s a heart-breaker. You’ll see.

Dorrance, on a raised wired platform, starts a duet with West who is below, on the stage itself. She recedes into the role of accompanist, generating a simple rhythm of sounds that remind me of the Sugar Plum Fairy’s celesta, as West pours and snakes his way onto his shoulder, his hands, back on his feet. West starts messing with an intriguing-looking wooden control panel near the front of the stage. Its wires and knobs allow him to control amplified electronic sounds; he turns on this one and then that one, like a kid with a Casio keyboard. Dorrance joins him, and you won’t know it just then, but you are poised on the edge of something.

What follows is a full-on eruption, sound and bodies hurtling in all directions. Dancers cross the stage, playing percussion instruments as they go. All the musicians are whaling on their instruments, the electric guitar is rocking out, limbs are flailing, taps are hitting the floor with furious frequency. The stage is fevered, the energy is at maximum intensity and there’s nowhere to go but oh yes, there is: Watts bursts into the center pulling out all the power moves, his legs flaring as he spins on his hands. Is this the climax? Or is this it, a minute later, when, impossibly, there is even more movement, more sound? I think there might even be smoke….

The only response possible at this point is to participate in the onstage bedlam: stand up with all the people around you, and clap and clap.

From 1993-2004, Veronica Dittman Stanich danced in New York and co-produced The Industrial Valley Celebrity Hour in Brooklyn. Now, PhD in hand, she writes about dance and other important matters.

Dorrance Dance continues through Friday, October 21 at the Power Center, 121 Fletcher St., Ann Arbor. For more information and tickets, visit: http://ums.org/performance/dorrance-dance/.