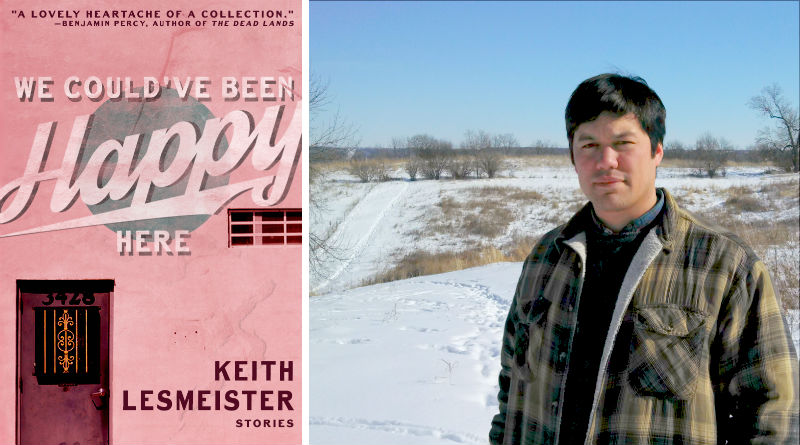

Clutch of Grit: Keith Lesmeister reads from "We Could Have Been Happy Here" at Literati

Keith Lesmeister's debut collection, We Could Have Been Happy Here, features a "gritty, emotionally sensitive clutch” of short stories, according to Kirkus Reviews.

That description that can be applied to a lot of Midwestern writers and Lesmeister fits the bill. He grew up in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, and currently lives in Decorah, which he describes as “much smaller -- a rural community located in the far northeast corner of the state.” The author's life experiences hum in the background of this collection, but the stories aren't autobiographical. What he learned from diving deeply into Iowa, he said, is how to better connect with people whose experiences are immensely different than his: “I spent a lot of time with characters whose lives are unlike mine in many ways -- I’ve never driven around with my suicidal grandmother; I’ve never experienced a deployed parent; I’ve never felt betrayed by a twin brother; and so on and so forth.”

On June 16, Lesmeister reads from We Could Have Been Happy Here at Literati. We chatted with him about Iowa, what makes a good short story, and more. Spoiler: Lesmeister’s so excited to read in Ann Arbor that he might even bake a cake.

Q: You said you learned how to better connect with people who are very different from you, with characters whose lives are not similar to yours. Writers are often encouraged to write about what they know, but your collection succeeds in bucking this advice. How did you approach "connecting" with these characters?

A: You're right: most writers starting out are given the advice to write what they know. I was given the opposite advice, which was to explore characters and situations vastly different from my own. And your question is spot on: How does one connect with a character who is unlike him/herself? I think the answer lies somewhere in the search for our shared sense of humanity: What do we fear? Love? Despise? What are our ambitions? Wants? Desires? What are our insecurities? Vulnerabilities? These answers, for each character, emerge after spending time on the page with each. In other words, putting those characters in impossible situations to see what they might do or say. One of the delights of being a fiction writer is that process of discovery and surprise. There's no greater surprise than when a character starts to act out on his/her own, independent of what I might want him/her to do or say.

Q: Since last year’s election result, there has been an elevated interest in understanding the nature of the Heartland/Rustbelt/Midwest and the motivations of the residents who populate these areas. Obviously, it’s challenging and perhaps impossible to describe such a large place with lots of people broadly. What's your take on this question?

A: I’m not sure how to answer this, so let me share a brief anecdote. I was talking with a few guys prior to Iowa’s first in the nation caucus. This was January 2015. The men were from a small neighboring town to Decorah and worked in the trades -- plumbers, electricians. We got talking politics and I asked them -- after a few beers -- if they were planning to caucus, and if so, for whom? They all answered, “Bernie, he’s the best candidate.” I said, “Sure, great, but what if he doesn’t win the nomination, what then?” And they all answered in unison, “Trump, no question.” Somewhere in their answer, I think, is a deep distrust for traditional politicians and a yearning for someone who speaks to the interest of blue-collar workers. The same thing happened in 2008 and 2012: Iowa voted for Obama, a less than traditional candidate in that he had very little political experience (nationally), but he spoke to the concerns of working-class families in a believable, authentic way. I think blue-collar Midwesterners yearn for that support from their candidates.

Q: Related, the Kirkus reviewer noted: “Lesmeister's vision of Iowa isn't exclusively somber, though. He can bring wit and lightness to these dirty-realist tales.” This balance seems somehow key to a good short story to me. What makes a good short story in your view?

A: I think it starts and ends with fidelity to characters. Which is to say, allowing the characters to be fully him or herself without authorial heavy-handedness. Abdicating this control is difficult, to be sure, but necessary for any amount of surprise and discovery in the narrative, which, for me, are the signs of a successful story -- surprise and discovery.

Q: You reside in the Midwest and your stories take place in the Midwest. Are there Midwestern literary voices that have resonated with you or have provided inspiration for your writing?

A: The last few books I’ve read, though well after putting this collection together, are Jane Smiley’s The Age of Grief and Marilynne Robinon’s Home and Lila. These three books haven’t shaped this collection, necessarily, though I would love it if any amount of their respective genius (Smiley’s and Robinson’s) influenced my future work.

Q: You’re reading with Alexander Weinstein and Marlin M. Jenkins. Do you see thematic connections here?

A: I'm honored -- and thrilled -- to be reading with Alexander Weinstein and Marlin M. Jenkins, wonderful writers whose work focuses on the immediacy of our society's needs. For instance, climate change, politics, and the dismal failures of unfettered capitalism and its extreme impact on those living on the economic fringe, certainly, but also middle and working-class families. Each author explores current events in ways unique and lyrical, timely and urgent, and while I confess to not being as adept at writing about those same issues, as Alexander and Marlin, I do hope my work brushes up against those same ideas. In this way, I think readers and attendees of our event, will see a diverse set of readings which ask similar questions, such as: How do we, as writers, respond to the growing needs of a polarized community?

Anna Prushinskaya is a writer in Ann Arbor. Her collection of essays, A Woman Is a Woman Until She Is a Mother, is forthcoming from MG Press in fall 2017.

See Keith Lesmeister at Literati, 124 E. Washington St., Ann Arbor, on June 15 at 7 pm. He will be joined in reading by Markin Jenkins, a graduate of the Helen Zell Writers' Program, and Alexander Weinstein, author of "Children of the New World."