Shifting Ideals: "GLOSS: Modeling Beauty" at UMMA

GLOSS: Modeling Beauty is a thoughtfully curated exhibition that focuses on the impact of fashion photography on the history of photography. The show explores “the shifting ideals of female beauty” in American and European visual culture starting in the 1920s with the work of Edward Steichen. The exhibition examines not only fashion photography and images from advertising campaigns but features documentary photography by Elliott Erwitt, Joel Meyerowitz, and Ralph Gibson, captured images of women and mannequins in urban environments. Furthermore, artists James Van Der Zee, Eduardo Paolozzi, and Nikki S. Lee “employ the visual strategies of traditional fashion photography, while offering alternative narratives to mainstream notions of female beauty.”

The works in the show are chronologically arranged, offering a cohesive narrative of the evolution of fashion photography and its intersection with fine art practice. The exhibition illustrates the progression from what we consider traditional studio portraiture to the edgy fashion photography that developed in the mid-late 20th century. Additionally, “beauty” becomes ambiguous in later works such as those by Andy Warhol, Helmut Newton, and Guy Bourdin, in which everyday life is portrayed as banally juxtaposed with high fashion.

Color comes in to play in the later works, both from advents in technology and reference to Pop Art, as seen in the Paolozzi works. In his series General Dymanic F.U.N., he satirizes popular consumption not only through imagery but in the choice of title. In these works, women are often depicted alongside technicolor food, referencing both domesticity and mass consumption while creating a sense of irreverence. His work consciously critiques the mechanisms of advertising and mass media by culling images from broader culture and translating them into colorful photolithographs.

Bourdin’s images from the late 1970s were shot for a Bloomingdale’s catalog and feature a B-movie aesthetic. The series features women in hotel rooms, with dim lighting and a sinister atmosphere that exemplifies the transition in fashion photography from the studio conventions established by Steichen in which lighting was carefully planned, to the edgy, haute couture of the later part of the 20th century. Additionally, Warhol’s Polaroid images are snapshots that would later be used to create his iconic silkscreen portraits, and again show the departure from traditional studio portraiture while illustrating photography’s impact on Pop Art and contemporary art in general.

Gloss: Modeling Beauty was curated by Jennifer M. Friess, hired in 2016 as the first assistant curator of photography for University of Michigan Museum of Art. (Her first project was Ernestine Ruben at Willow Run: Mobilizing Memory. She will be working on a number of exciting upcoming exhibitions featuring the museum’s excellent photography collection. Below, my conversation with Friess explores some of the themes and narratives within the show and offers a glimpse into the next photography exhibit at UMMA.

Q: What was your initial inspiration for this exhibition?

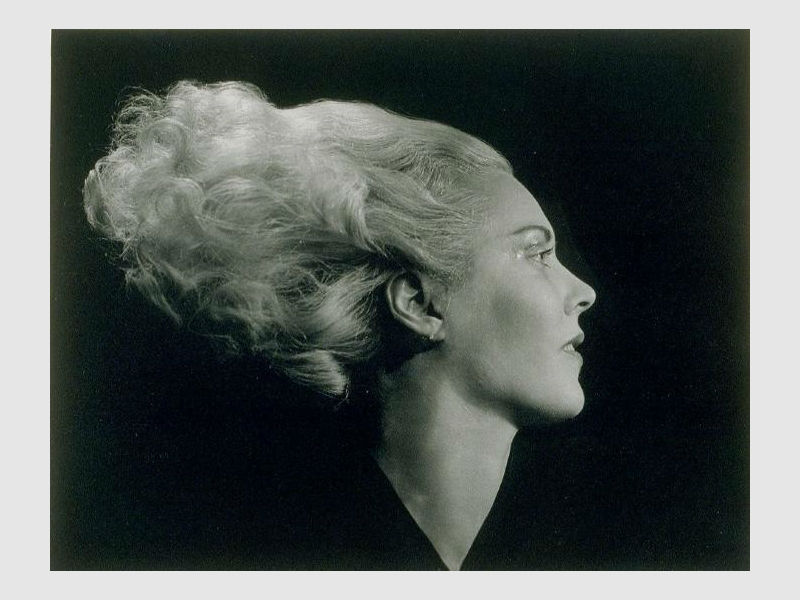

A: I think when I first got here, and when I first took on the role of assistant curator of photography, I was in a position to be the first photography curator here at UMMA, and so I had this whole collection to dive into and research. It was really some of those early iconic images by Steichen and Philippe Halsman that started that conversation in my head. As I explored the collection more and more, there seemed to be a kind of narrative that emerged, not just about fashion photography, but how women are represented throughout the history of the medium. We have a fairly strong collection of images that just depict women in the service of fashion photography.

Q: So, women in fashion photography are often not considered the subjects of “fine art” or “high art”; were there any challenges when you were searching through the collection to gather enough subject matter to realize this exhibition?

A: That is a great question. There is, of course, always a speckled history of how different types of photographs are included in a museum collection. When Steichen was photographing Greta Garbo, his images were published, and not always concurrently, in Vanity Fair. So, to think of images that were consumed by a mass public, through a mass publication, thinking of those in 1928 as being in a museum collection was quite unusual and unheard of. Now, decades later, we see that the work they were doing, even though it was consumed on this mass level, is actually really significant to how fashion, culture, and even broader Pop culture evolved. These images are really quite significant to the narrative and history of the last 60 to 70 years.

In terms of what we had in the collection, these images, so many of them were not considered fine art when they were first made. There is a sense that their importance grows over time, and we have amassed a certain number of these throughout the decades that allowed for a cohesive narrative to be told. And of course, photographers like Nikki S. Lee and Josephine Meckseper are very purposefully working in a “fine art” milieu, and so they sort of bookend the narrative where photographers are becoming much more active and critical of past established techniques and subjects. It was a fitting end to this narrative, starting with someone like Edward Steichen, who basically made a name for fashion photography in the first half of the 20th century, and ending with women photographers who are challenging that narrative.

Q: Could you talk a little bit more about the Nikki S. Lee and the Josephine Meckseper, and how you used those to kind of counteract the narrative of fashion photography?

A: What’s so great is they are making that choice. For example, Nikki S. Lee, a Korean photographer, is actually inserting herself into these images, making self-portraits out of very constructed and staged tableaux. She is, throughout her career, inserting herself into situations and social groups in which she might not otherwise be privy. She dons these different personas, and then photographs herself in these situations.

The image in this exhibition is from her broader Parts series, and she is inserting herself into this upper-class, French, bourgeois environment. There are a few hints when you look at the image that things are constructed. For example, the perspective down on Nikki S. Lee is not as if we are looking at her walking the red carpet from a natural eye-level; instead, she is photographing from above so that you can really see not only her in the setting, but how the setting itself, the stairway and decadent gold-rimmed everything, plush carpets, and marble, it all envelopes her in the center of the image. In addition, you can tell by looking at the image there is a pretty thick white border around the photograph, and she is actually cutting away one side of the image in order to indicate that she had a very conscious hand in making it. In doing so, by cutting the image, she is actually cutting out the male figure, and that is where the meaning of the Parts series comes into play, in that she is only including parts of the male figure. He (whether it is one he or many) is always present in the periphery, she is just changing the focus of her images.

With Josephine Meckseper, she is doing something that has its basis in early Pop Art, in that she is culling images from mass media and altering them in a significant way. She is continuing that narrative begun by Steichen and Halsman, but by pulling images from fashion photography, from publications, and then altering them in some way. Whether by turning them upside down, painting on top them, but in some way she is reasserting her hand in the making of the objects.

Q: I am wondering after that discussion which piece, if any, or which series is your favorite?

A: All of them are my favorites really, it is hard to choose. The Guy Bourdin’s are my favorite. They are so bizarre and so dark, and really it is a simple premise. He is taking images that advertise Bloomingdale’s recent -- and by recent I mean 1976 or so -- lingerie line. That premise in and of itself is quite mundane and is not something new at all. People had been photographing each new season’s clothing line and lingerie line for decades. Here you have him putting models in these lingerie outfits and pajamas, and he is staging them in really curious settings, and in various groupings. They are often very poorly lit, in terms of how studio portraiture should be, like Steichen, photographing properly lit models in a very controlled setting. It is almost as if he has let the reigns off in how the models are staged and how they are arranged, and the setting they are in, he seems to tap into his psyche.

His images are often quite edgy. Some of his more iconic images involve Dobermans growling and interacting with models. There is often an aggressive vibe to many of his images. These are slightly more tame than even those, but there is a sense of magic and mystery that he is invoking in the images. The objects themselves are also quite glossy, they are printed on this very vibrant, glossy, color paper, and he just makes them irresistible. The narratives that he is suggesting are not ones that you would find in daily life, and I think that makes them pretty intriguing.

Q: These Bourdin images, aren’t they somewhat rare? They are not very well-known?

A: They are, this is one of his lesser-known series. Because he is publishing it for Bloomingdale’s, it was meant to be viewed in a catalog, not necessarily on the walls of a museum. It is kind of a rare glimpse for viewers to see these objects on display. They are part of a broader series as well, we just have a sample of six out here on view.

Q: Is that true for many of the works in the show, that they are kind of out of context from their origin?

A: Yes, it is kind of interesting, so often with photographs, any photograph really, especially earlier images, they are often taken out of their original context. That is true of many works of art that were made before 1950 or so, but the idea of these photographs having a real, physical life outside of the museum is pretty ubiquitous throughout the show. Some of the later artists are very consciously making art that is meant for a critical museum context, like Nikki S. Lee or Josephine Meckseper. People like Bourdin are photographing for Bloomingdale’s, and Halsman and Steichen, whose images were meant to be in editorials and magazines, for LIFE and Vanity Fair. Those images came from somewhere, those prints were made and used as proofs, so they have many, many lives before they came to the museum. Always remember when you are looking at a photograph in a museum, these objects had a physical life before.

Q: That’s really interesting! I am also curious, since you mentioned you are the first curator of photography at UMMA, how has this experience been so far for you, and do you have any exciting plans for the future of the collection?

A: That’s a wonderful question! I am taking the collection over from our former Western art curator, Carol McNamara, and she did a wonderful job exploring the collection. Even our photography gallery space was just created in about 2014. It is a fairly new space, and it is new to have me as the single steward of the collection. I am excited to get these objects out on view, there is so much in our collection that I am going to be bringing out in future exhibitions, and it is pretty exciting to both grow the collection and put it on view for an audience, frankly, that is quite interested in photography. Of course, photographs are so ubiquitous now, and everyone has a camera phone, you have access to your life’s images at the touch of a button. I think there is a real relevancy to the medium right now, even though there is this deluge of images. My goal is to help sort through that deluge, and give you some glimpses and narratives to hang onto, use, and bring back.

Q: I am very excited for upcoming exhibitions, and that is my last question: Do you have any upcoming projects that you are looking forward to?

A: I am looking forward to all of them, but after GLOSS is a show called Aftermath: Landscapes of Devastation, and it brings out images from almost the entire history of the medium, and shows scenes of natural and human inflicted destruction and devastation. They are all landscape images, and represent scenes of destruction. However, not all of the images were made immediately after the event. We have scenes of the Civil War, for example. An image just after the battle of Gettysburg is paired with a photograph by contemporary photographer Sally Mann, who is revisiting the antebellum landscapes of the Civil War era, re-photographing them in a way that is almost like a dream-like state. So you see a chronology of events, but the images themselves play with the idea of remembering and memory.

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

"GLOSS: Modeling Beauty" is at UMMA, 525 S. State St., through January 7. Visit umma.umich.edu to see talks and events related to the exhibition.