Yvonne Rainer's movies dance away from the mainstream at the Ann Arbor Film Fest

If you don't yet know the work of Yvonne Rainer, after the 56th annual Ann Arbor Film Festival, you most certainly will.

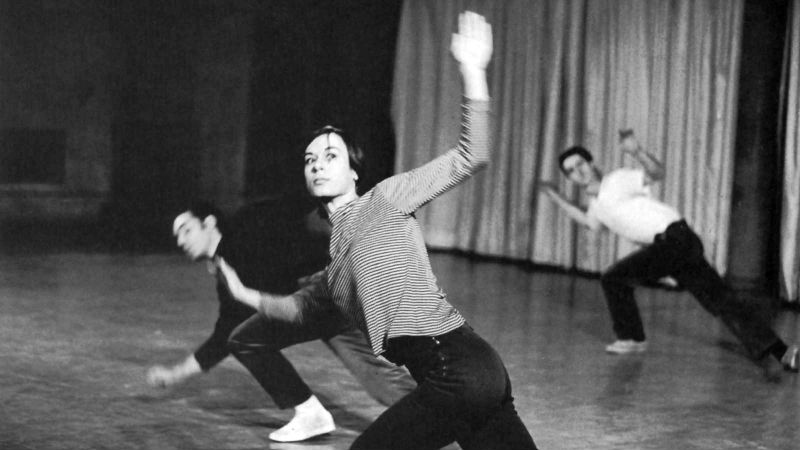

The post-modern dance maverick and her work will be highlighted during AAFF, which runs Tuesday, March 20 to Sunday, March 25. Rainer, who is known for her provocative style of dance and fragmented narrative style of film, began her career in the 1960s as a founder of the Judson Dance Theater. She then transitioned to film-making in the mid-'70s. After making seven experimental feature-length films, Rainer returned to choreography in 2000 when she choreographed After Many A Summer Dies a Swan for the Baryshnikov Dance Foundation. Currently, Rainer works with a troupe of talented people who take her dance to Europe and across the United States.

Rainer will present her essay-turned-lecture "A Truncated History of the Universe for Dummies: A Rant Dance" at the Michigan Theater on March 22 at 5:10 p.m. as part of the Penny Stamps Speakers series. (The documentary Feelings Are Facts: The Life of Yvonne Rainer screened at UMMA on March 7.)

On March 23 at 7 pm, Rainer's sixth feature film, Privilege, will be shown at the Michigan Theater screening room. Privilege is a pioneering take on menopause and was called her "most accessible film" by the Village Voice. Five Easy Pieces, her collection of short films made 1966-1969, screens Saturday, March 24, 4 pm at the Michigan Theater.

We chatted with Rainer about Privilege, Five Easy Pieces, filmmaking, and dance.

Q: It’s been over 25 years since the original release of Privilege. Do you feel that there has been more exploration or experimentation in film regarding women’s sexuality and women’s health?

A: Well, yeah, of course, there are more women making films. What can I say? Yeah, I don’t follow the field that much but I just have a sense that there are more women out there. I’m trying to thinking of a recent film I saw. Well, I have friends who are still going at it. Su Friedrich is still making personal, experimental films. I don’t know. It’s very hard to collect my thoughts on this matter. When I was involved in film, I mean that’s the trouble now -- I don’t keep up because I’m more involved in dance -- there were many, many women whose work I followed.

Q: Privilege is a kaleidoscope cinematic devices and social narratives throughout the film. Do you think the themes of multiculturalism, rape, and racism are amplified by the current social climate right now?

A: Yes, that is definitely the case especially with black, male filmmakers. I mean, I watched the Oscars and I’ve seen a couple of those films -- Get Out and several others. The political situation now with women coming out from the woodwork talking about predatory guys and the de facto segregation that goes on in this country, and has been for years, is being revealed in these films. 12 Years a Slave is another film that is current. So all of this is happening at the same time and I hope that it challenges the Hollywood creaky authoritarianism is going to open up to more people who have been on the margins.

Q: To piggyback off of that, do you think broader audiences could be able to glean more of that the intersectional narratives of the Privilege now opposed to 1990?

A: You mean that audiences will be more acceptive of the so-called “outsiders” work? Well, yeah. They all have their own following and the fact that mainstream films are being shown. I mean, it’s a long way from the '60s when all we had was Look Who's Coming to Dinner. So yeah, something is happening, I sense it.

Q: Do you feel that that change is complemented in the dance world as well?

A: Well, there has always been black dancers and choreographers, as it has been for women. It has been a more acceptable, more prevalent recourse for women to become dance [choreographers]. I mean, I didn't have any trouble in terms of gender in being able to study dance in the '60s. But it’s certainly different in ballet than it is in modern dance and postmodern dance. Only now, for instance, the New York City Ballet is opening the door to women choreographers. So that is, I think, because dance somehow reinvents the wheel and maintains the same kinds of closed and conventional ways of doing things. So it's been a slow progress to allow more women into the classical field to become choreographers. But I have this background of the great [artists] -- [Martha] Graham and [Doris] Humphreys and Isadora [Duncan] even -- not only as support but as people to challenge and take off from and go in a different direction.

Q: Your films, much like your post-modern choreography, there’s a lot of juxtaposition of the familiar and unfamiliar and then layers of commentary on social issues. Are there other elements in your films, particularly Privilege or MURDER and murder, that you would like audiences to be more aware of?

A: Well, they don't need me, but certainly my transition from dance to film was because I wanted to deal with topical and autobiographical subject matter in terms of gender, sexuality, and challenging my own upbringing in terms of racism as a white, privileged person. So these issues are very prominent in those films you mentioned. I mean, the last one represents my own transition from heterosexuality to living and recently marrying a woman. I’ve always had a specialized audience; it’s not a general audience, partially because of the venues which are hospitable to my work. And it's my interest in combining pedestrian and everyday movement and trained technical movement. You know, it’s not for everyone -- the kind of junctions and the what I like to call “radical juxtapositions” -- to use a Susan Sontag term. So when you speak of an audience, there are people who have always followed my work and followed it in film and followed it as I returned to choreography.

Q: You mentioned incorporating feminism, racism, and multiculturalism. Is there an aspect of a theme that you haven’t experimented with that you would like to, whether that be in film or dance?

A: I have a group and it contains choreographed movement. They’re [her group] all trained, highly trained -- one used to dance with the New York Ballet -- but they have options. There is a lot of indeterminacy in the work. My work is not thematic. There is not a single theme that is represented in a particular work, so I guess this trope of unpredictability is something I have gravitated to. But right now, in my early work, there are about seven dances that have survived from the '60s. None of them were documented, but I kept some pretty good notes I can reconstruct. [New York's] Museum of Modern Art has gotten interested. The venue that hosted these works for me and my contemporaries at Judson Church in New York. So, these works will be revived in the fall. Meanwhile, I’ve been writing a lot -- a long essay, which I will deliver. It’s a lecture -- a kind of performance lecture, which I have gotten kind of obsessed with, will present in its entirety in Ann Arbor. So that’s what I’ve been involved with recently.

Q: Do you plan to continue more essay/lecture performance writing or do you plan to return to choreography or filmmaking?

A: Not filmmaking and certainly not feature-length filmmaking. It was just too hard. I’m kind of a techno-dummy and the whole process of waiting around. The budget was always too small. There are too many mistakes, and a lot of the time I was on my own and in over my head. A friend of mine in Britain, Peter Rollin, used to say, “They let you make five.” Well they, the powers that be, they let me make seven. And by the end in 1996 with MURDER and murder, I figured I’d had it.

Coming back to dance was a big relief. It felt like coming home. So, I’m still involved with making some kind of dance and I have a group of very devoted people. I feel very lucky. There are six of them and we were recently in Europe. ... For a long time, museums have been interested in performance and dance, so these are the most hospitable venues in recent years -- both in Europe and the U.S.

Q: Five Easy Pieces and Privilege will both be showing at the AAFF on March 24, along with a performance of Chair/Pillow.

A: Five Easy Pieces -- each was more or less the length of the reel of 16mm film. They were all made within a year, year-and-a-half in the late '60s and were preliminary. They all had one idea -- like 10 minutes in a chicken coop in Vermont with all these pecking chickens moving around, or two nude figures on a white sofa with a big balloon moving around. They were very in line with a minimalist aesthetic. I call them my short, boring films. They’re a curiosity but they were preliminary to the more ambitious, longer films that I began to write scripts for in the '70s and '80s.

Sarah M. Parlette spends her time freelancing, working at the AADL, and planning her next adventure.

Yvonne Rainer will present her essay-turned-lecture "A Truncated History of the Universe for Dummies: A Rant Dance" at the Michigan Theater, 603 E. Liberty St., Ann Arbor, on March 22 at 5:10 pm as part of the Penny Stamps Speakers series. This event is free. Rainer's film "Privilege screens at the Michigan Theater on Friday, March 23, 7 pm and "Five Easy Pieces," her collection of short films made 1966-1969, screens Saturday, March 24, 4 pm. For a 15% discount, enter the code AAFF56_AADL when you purchase tickets.

Comments

Thank you so much

Thank you so much