Polly Rosenwaike's stories give an intimate glimpse into the contexts of motherhood

This story was originally published on March 29, 2019.

Women who want babies. Women who do not. Women who try hard for a baby, and women who easily become pregnant. Women who lose a baby, and women who have one.

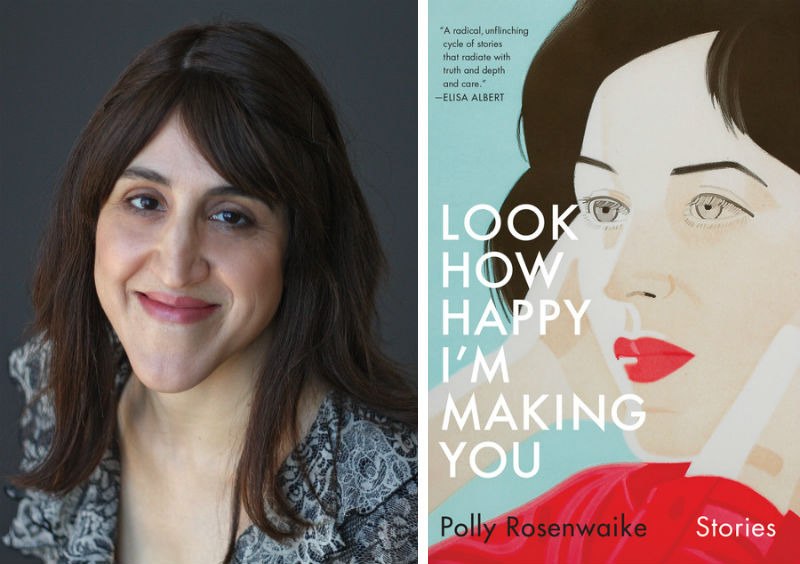

These women populate the stories in Look How Happy I’m Making You, the debut collection by Polly Rosenwaike. Efforts to conceive and be mothers -- and the effects of those efforts on these women -- engage them.

Rosenwaike’s stories, however, do not only center on the processes and acts of conceiving, birthing, and parenting. This collection moreover illustrates the complexities of the feelings and relationships surrounding motherhood and the wish for it.

Rosenwaike draws inspiration from her own experiences as a mother and often works from branches of the Ann Arbor District Library. A resident of Ann Arbor, she is the fiction editor of Michigan Quarterly Review, is widely published in literary magazines, reviews books, teaches at Eastern Michigan University, and has two daughters with her partner, poet Cody Walker.

Rosenwaike will read and discuss Look How Happy I’m Making You at Literati Bookstore Wednesday, April 3, at 7 pm. She answered questions about life in Ann Arbor and her new collection.

Q: What brought you to Ann Arbor?

A: In 2009, my partner, Cody Walker, got a position teaching in the University of Michigan English Department. I’d just finished an MFA program in New York and was ready to move somewhere calmer and more affordable, though I missed the big city at first. But here I found the coziest (park-lined) street to live on; the nicest neighbors; wonderful schools for our children, who were born here; and a variety of satisfying jobs, teaching creative writing and doing freelance editing. Ann Arbor has been very good to me, and may I take this opportunity to say how much I love the public libraries? I came up with the idea for my story collection while sitting at a desk at the Malletts Creek Branch of the Ann Arbor District Library. I’ve spent many weekends working in companionable solitude at Westgate. I continue to plant my young daughters in front of the mesmerizing fish tank at the Downtown branch. What more could I ask for?

Q: Look How Happy I’m Making You is your first book. All of the stories coalesce around fertility, conception, pregnancy, and childbirth. Tell us about this collection.

A: I worked on the 12 stories in the collection for over a decade. Though they’re each about different characters, they’re thematically linked, following women at a certain time in their lives -- late twenties to early forties -- who are contemplating motherhood, as well as encountering changes in their relationships with friends, family members, and romantic partners. The book begins with a couple having difficulty conceiving, and then moves through a chronology of characters’ experiences with pregnancy and new babies in their lives. It ends with a story about a couple who’ve almost made it through their baby’s first year, but are desperate to get her to fall asleep on her own: the quintessential new-parent problem.

Q: You are a mother of two daughters. How does motherhood influence your writing and inspire your stories?

A: If I hadn’t become a mother, I wouldn’t have written this book. The experience of having children was so fascinating and challenging to me that I felt compelled to write about it and to persist in finishing the collection. As my daughters get older, their burgeoning creativity and interest in the power of narrative keeps me attuned to the playfulness of language and the structure of stories. My eight-year-old fills file folders with all of her papers -- she seems to write just for the pleasure of getting things down -- and she’s penned several longer works, including The Month Book (chapter titles include “January is the Worst!!!!!!!” and “April is Eggy!”) and Don’t Tell My Boss. The five-year-old tells us stories before bed, her eyes widening as she delivers the suspenseful parts. It’s been a joy to see up close how intuitive and important storytelling is for children. When my older daughter was about five, we were a few pages into a new picture book when she asked, “What’s the problem going to be?” She had articulated the fundamental rule of fiction: there has to be a conflict. My kids inspire me to try to develop conflicts that are worth writing about.

Q: Since you are the fiction editor for the Michigan Quarterly Review and have taught creative writing at Eastern Michigan University, it sounds like you eat, breathe, and sleep writing! How does this work interact with your own writing? Does it ever feel like too much fiction?

A: Too much fiction -- yes. Sometimes I turn to nonfiction or poetry! I’m a little boring, I admit, in my singular focus. I don’t play any sports, or garden, or practice any instruments these days -- I played flute (not especially well) in high school band. Once upon a time, in my twenties, I was learning Russian and dancing salsa. But reading and writing have always been my great loves, and I’ve been really happy for the opportunity to teach and to work as an editor over the past decade that I’ve been living in Ann Arbor.

Q: What draws you to short stories?

A: As a writer, the short form appeals to me in part, honestly, because it’s short. I enjoy creating a moment in time for a particular character, making just a few crucial things happen that shape her in some way, and then leaving that character there, done. I have an affinity for writing endings, though not so much plot-heavy middles. I like how the limited space of short fiction demands precision and the careful selection of details. As a reader, I do often crave immersion in a created world for an extended period, like other devotees of hearty novels. But I’ve found that short stories can leave the greatest impact on me, and I love assigning them to my students at Eastern Michigan University as brilliant portrayals of life’s mysteries. On desire, there’s Jamaica Kincaid’s lyrical “Song of Roland”; on the painful absurdity of American culture, George Saunders’ “Sea Oak”; on the stunning fragility of existence, Tobias Woolf’s “Bullet in the Brain”; on the experience of trying to write fiction, Lorrie Moore’s “How to Become a Writer.”

Q: As you mentioned, Look How Happy I’m Making You focuses not only on motherhood but also on relationships, such as in the story about a woman who nears giving birth to her daughter while her aunt is dying. The configurations sometimes come about by design of the characters and sometimes by chance -- and sometimes it’s both, such as Serena who doesn’t want a child, but her husband Henry decides he wants one after all, so they have one in “Love Bug, Sweetie Dear, Pumpkin Pie, etc.” These relationships run parallel to the attempts to conceive, pregnancies, and childbirth; they reveal complications and desires. The stories show how having a child is very much connected to the context in which it happens. How did you assemble the various relationships and situations into which people are having -- or not having -- a child in this collection?

A: I wanted to depict a range of relationships -- within families, between female friends and romantic partners. Having a baby is often perceived as a natural, inevitable, and entirely joyous trajectory for a committed couple, but the reality can be complicated and fraught. Sheila Heti’s autofiction Motherhood, which came out last year, is an almost 300-page rumination on the difficulty of deciding whether or not to become a mother. The decision to have a child is such a major one, and I find it intriguing how people think through their decisions, or don’t think through them, and then have to deal with the consequences.

Q: The women in Look How Happy I’m Making You frequently have to make choices, yet they don’t get to make some choices in regard to motherhood. Caitlin realizes that she cannot be with her boyfriend Kamal and his daughter Laila in “A Lady Who Takes Jokes.” Cora has a miscarriage in “Period, Ellipsis, Full Stop.” A woman struggles with being a new mother in “Ten Warning Signs of Postpartum Depression.” This contrast between choice and powerlessness shows how having a child, or not, is not straightforward in the way that the question of whether or not to have one seems. How did you consider elements within and outside of the characters’ control when writing these stories?

A: If you have a miscarriage -- as I did, before having a successful pregnancy in which I carried a baby to term -- it’s a harsh reminder of how little control you have over the process. We attempt to fashion our ideal pregnancy and childbirth experiences, and it often doesn’t work out how we envisioned. My partner and I took a childbirth class at The Center for the Childbearing Year in Ann Arbor, and I remember the facilitator mentioning the percentage of women who end up with a C-section. I looked around at the group of us who were trying to prepare for a vaginal birth and thought, statistically, at least two of us are likely to have C-sections. I turned out to be one of them. There’s a good deal of uncertainty and risk in this endeavor, and it can be frightening that it all happens within our own bodies. Women often feel responsible for outcomes that they have little to no influence over.

But to back up, before the process even starts, there’s that maddening fact of female biology that we’re only fertile for so long -- and what do you do when you want to have a child with someone, but you’re not finding that someone who you really love, or who wants to commit to you? So yes, I think questions of both what’s within our control and outside of it are very challenging to face in real life, and thus interesting to address in fiction.

Q: Yes, there is the precarious relationship in “The Dissembler’s Guide to Pregnancy” in which Finn is noncommittal and his girlfriend hangs on tightly to having a child and being with him. The narrator considers W.H. Auden’s poem about how stars do not love us back, and she decides it’s preferable to “be the one lit up with want.” Such strong, summative insights and thoughts are sprinkled throughout the collection. In your writing process, do these reflections come to you as you are writing, or do you think of them at other times and fit them into stories?

A: For years, I thought about using Auden’s beautiful poem “The More Loving One” as the poetic heart of a story about an imbalance of desire in a relationship. I began writing “The Dissembler’s Guide to Pregnancy” probably about a decade after I first had that idea, and I was thrilled when I realized how it could fit in this story. I carry a lot of fragments of images and language around, and it’s one of my favorite things about writing fiction to find a way to incorporate them into a story container that feels right to hold them.

Q: The intimacy and honesty of these stories feels like peering into the characters’ private lives and minds. Characters recognize flaws in their thinking or their actions, while simultaneously babies are conceived, or not, and may, or may not, survive. How do you approach these personal topics and situations?

A: I took a lot from my own experience for this book, while also imagining characters in more extreme, conflicted situations than I’d been in. Fiction has always been a space of intimacy for me, a place to explore emotion without explicit judgment, to recognize the contradictions that lie within people’s relationships with others and with themselves. When I teach introductory creative writing classes, I begin by talking to students about Franz Kafka’s famous line, “A book must be the ax for the frozen sea within us.” We all have fears and longings we keep inside, and sometimes even keep half-hidden from ourselves. Writing can be a means for trying to hack away at that frozen sea. And by doing so, perhaps we can reach others in their deepest places. That idea is powerful to me and keeps me pushing through the hard work of writing.

Q: Finally, what are you reading and writing next?

A: I’m currently reading the Portland writer Leni Zumas’ novel Red Clocks, as I’m anticipating being in conversation with her at Powell’s Books soon. Red Clocks is fantastic -- full of empathetic and complicated female characters, rich details, pitch-perfect dialogue, and political relevance. I’m feeling very pro-novel! Which is good, because I may try to write one next, and I need all the positive energy I can muster for the task.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Rosenwaike will read and discuss "Look How Happy I’m Making You" at Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor on Wednesday, April 3, at 7 pm.