Ann Arbor Art Center's "Peripheral Technologies" juxtaposes modern techniques with classic craft

With Peripheral Technologies, curated by Thea Augustina Eck, the Ann Arbor Art Center continues its trend of bringing together a diverse group of voices who ask us, through their works, to reconsider the limits of fine art in an era when we are constantly being asked to do so.

The types of technology employed by the 12 artists -- and how they can be adapted for the creation of art -- are numerous, among them CNC (computer numerical control) machining, image scanning, computer-generated algorithms, and drone photography. Many artists pair emergent technologies with traditional or natural materials such as wood. These pairings create intriguing juxtapositions that ask viewers to consider our current technological moment in relation to manufacturing methods of the recent past. The artists come up with a different conclusion through methods, materials, and their finished works.

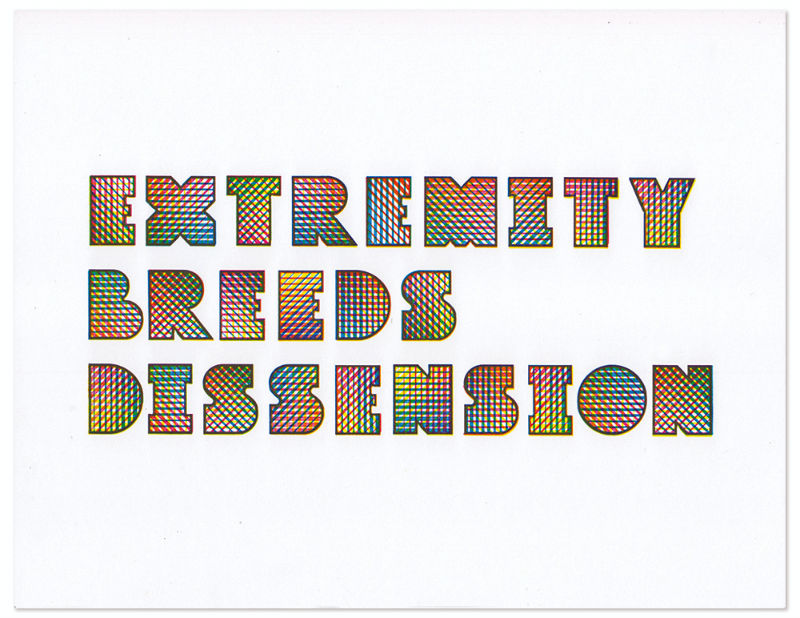

Ryan Molloy is an Ann Arbor-based artist who employs both contemporary and modern technologies in his artistic practice. Molloy is involved in type design and typography, primarily working with milled-wood type used in letterpress printing. His final works are created by melding methods from past and present. The finished graphic typeface on display as a part of Molloy's asynchronous idiom series may appear simple, but it's extremely labor-intensive to produce, as each color must be printed by hand on top of the previous color. In the digital age, a graphic phrase printed with multiple colors could be easily created in a graphic design program and printed all at once, but with manual printing, each letter must be placed by hand. When it comes time to print the final piece, each color must be done separately and allowed to dry, then placed exactly in the correct position. Molloy's vibrant and complex letterpress works illustrate the amount of time that can go into such a project, while it may appear effortless as a finished product.

Sophia Brueckner has two works on display in Peripheral Technologies. First, Window #5, polyurethane and acrylic, is part of a larger series, Windows, which Brueckner describes on her website: “Windows is a series of paintings derived from the 1993 DOS computer game Lands of Lore: The Throne of Chaos. Using computer code, I translate the condensed landscapes seen from tiny castle windows within the game to 3D models. I fabricate these forms on a CNC milling machine and then paint by hand the original images back onto the objects.” For this series, Brueckner uses not one but three peripheral forms of technology.

Brueckner's second piece in the exhibition is a video, Captured by an Algorithm, which was recently on display at the Clark Library as part of the University of Michigan’s Bookmarks exhibition. The video is made with JavaScript, which “scrolls through Kindle Popular Highlights from top romance novels layered on top of hundreds of pieces of scanned romance novel covers that were stitched together by Photoshop’s Photomerge algorithm. Over 60,000 individual acts of highlighting went into making this work.” Though the works employ technological means in their creation, Brueckner is involved in the creation and curation of the work. She observes that while algorithms seem to “flatten human experience,” the work done in Captured by an Algorithm reveals incredibly vulnerable emotions via romance novel enthusiasts.

Peter Baker is an Ann Arbor-based photographer and his Peripheral Technologies presentation is a collection of six photographic images taken with unmanned aerial vehicles, aka drones. The images are all aerial views, the artist points out, and they are “too low for helicopters and planes and too perpendicular to be taken from a high vantage point.” The specificity of this vantage point then relies on the ubiquitous new technology of the drone, presented in a painterly view on metallic paper. Baker’s statement draws attention to the increasingly-image saturated world that we now inhabit, which for a brief moment sees a new, unique photographic perspective.

Christy Oates contributed three works to the exhibition, each a unique woodwork. Oates has a background in manufacturing and furniture making, and she uses CNC machines such as laser cutters and routers to create her works. The three works on display are part of the Kaleidoscope Algorithm series, in which “computer manipulation algorithms translated to wood marquetry.” The kaleidoscopic images resulting from the algorithm draws together the art of manufacturing, peripheral technology, and the classic craft of marquetry. Each individual work corresponds to the top Google search trend for each day in September 2011. Each work has a QR code in the right corner, which, when scanned, will direct you to the related search results.

Matt Shlian is an Ann Arbor-based artist working as an engineer. Shlian uses paper for his engineering work, which is rooted in “print media, book arts, and commercial design.” Shlian has used his skills to create kinetic sculpture and collaborated with University of Michigan scientists. “Researches see paper engineering as a metaphor for scientific principles; I see their inquiry as a basis for artistic inspiration.” Shlian’s work Unholy 79 (in black) exemplifies the tedium behind the creation of his work, with its mass of accurately geometric shapes creating a 3D form that creates a composition that seems to move when the viewer walks around it.

Dylan Beck is an artist currently based in Portland, Oregon. His work explores the environment in relation to “the idea that we are currently living in an epoch where human activities have had a significant impact on the Earth’s ecosystems, known as the Anthropocene.” Beck notes that in our contemporary moment we are prone toward “an overwhelming trust in progress,” which is paired with “a general disregard for our relationship to natural systems and processes.” Beck’s wood-cut relief sculptures made with a CNC machine, titled SUPERSYMMETRY OR “DID YOU SEE WHAT THE GOD PARTICLE JUST DID TO US, MAN?? shows us three milled frames of wood, made to resemble a topographical map.

Stephen Cartwright is an artist based in Champaign, Illinois. His sculptures are an intersection between art and science, as he explains in his artist statement, “where hard data intersects with the intangible complexities of human experience.” In order to integrate this hard data into a visible, tangible form, Cartwright maps out the “exact latitude, longitude and elevation every hour of every day” and translates this into his signature “floating geometric forms” encased in acrylic resin. This is just one example of the kind of data Cartwright uses to create his abstract “landscapes.” Sometimes the floating forms are a single pigment or plane in the resin, and other times, like in his three-tiered work Floating Data (Email, Time at work, Time meditating 2016), two or three colors are employed to represent different aspects of the data from Cartwright’s day.

Lia Cook contributed two large fiber-based works to the exhibition. Cook’s works are complex, and appear to shift as the viewer moves around the large, rectangular hanging tapestry. In her artist statement, she describes how she creates these weavings, using “DSI (Diffusion Spectrum Imaging of the brain) and TrackVis software from Harvard to look at the structural neuronal connections between parts of the brain.” She then integrates “fiber tracks” from the imaging software and translates them into the “actual fiber connections” of the tapestry. The works can be unsettling, as the face shifts in and out of view depending on what stance the viewer takes upon approaching the object. Cook is concerned with capturing “subtle and dramatic variations [to] create vastly different emotional" effects. The bright color of the “fiber connections” contrast to the grayscale facial imagery in the background, further obscuring the subject and lending room for an ambiguous emotional reading.

Richard Elaver works with 3D printing technology to create many of his works. He works as a designer and metalsmith, merging the disciplines of art, design, and technology. Examples of his 3D printed, resin-coated sculptures can be seen in the gallery, including Bowl, created with his signature empty space that comprises most of the sculpture. The sculptures resemble functional objects with amorphous holes incorporated into the surface design. The vases, for example, are based on Tiffany vases, which the artist “deconstructs into cellular patterns using generative software.” Three pieces from his Wripple Series are also on display. These are wooden sculptures with a 3D aspect, which when viewed appear to resemble a rippled surface of water.

Jason J Ferguson contributes an absurd, large, rotating sculpture that bears an almost equally absurd title: Being, nothing more, CNC milled polystyrene, plastic, pearlescent auto finish, wood and motor, H 2’ x L 3’ x D 2’ Age 38. Volume 5,616.188 cubic inches. The sculpture physically resembles a metallic boulder rotating on a pedestal. In his artist statement, Ferguson delves into the meaning behind this work, which was created via CNC milling to match the exact volume of his body at age 38. Another notable work in the show is his wreath-like, mandala-like Revolve, CNC milled foam and epoxy, created from the repeated form of a rabbit’s head.

Finally, the works of Nervous System, a collaborative effort between Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg, represent the integration of technology into the production of affordable art, jewelry, and housewares. The artists employ generative systems, 3D printing, and WebGL to create collaborative designs for their clients. Nervous System works toward co-creation that allows online users accessible design experiences and allow for “endless design variation and customization.” Their contribution to the exhibition is titled Hyphae Crispata #1, and is part of their ongoing project working with the Hyphae (3D) system, which employs an algorithm that mimics the formation of veins in the body, then adapts the pattern for the object to be created, which can be “jewelry, lamps, sculpture, or even architecture.”

Whether working to create functional objects, non-functioning replicas of functional objects, or abstracted homages to technological advancement, the works in Peripheral Technologies expand the possibilities of art, science, and technology. New avenues are constantly explored for creators and consumers, and these artists ask pertinent questions. How can art and technology co-exist? How can technology enhance art, and can art enhance technology? What technologies can be revived when they no longer serve a purpose for large-scale production (looking at you, letterpress)?

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

Ann Arbor Art Center's Peripheral Technologies runs through July 6.