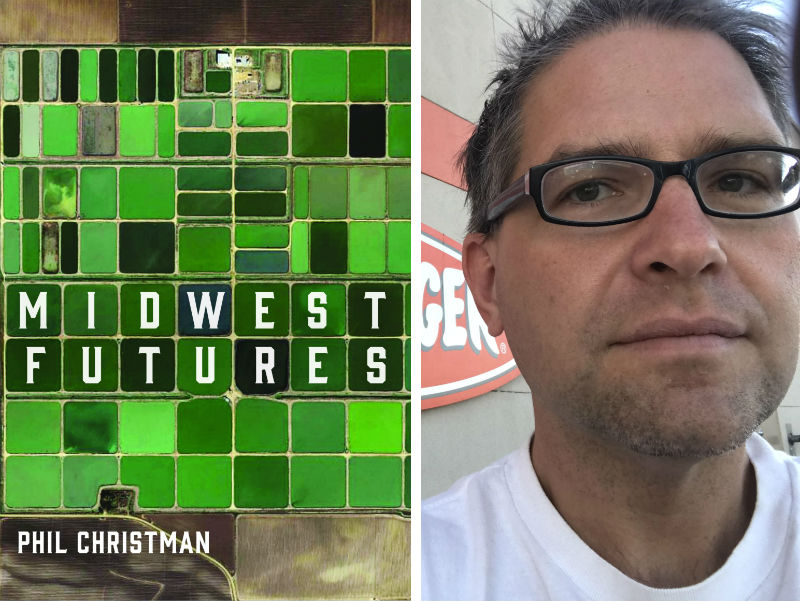

Phil Christman traverses time, politics, and culture in his nonfiction essay collection "Midwest Futures"

This story was originally published on February 6, 2020.

What words come to mind when you think of the Midwest?

You may think about its geography, the middleness, or its position and moniker as the heartland with farming and small towns.

You might look at a map to see the 12 Midwestern states (from east to west): Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.

Perhaps you reflect on its seeming representativeness of American life. Or you study its history containing the displacement of indigenous peoples, manufacturing, and struggling economies.

Myriad ways, even contradictory ones, coincide to describe and understand the Midwest. Writer Phil Christman navigates them in his new book, Midwest Futures, a wide-ranging set of 36 brief essays organized in six sections. Part criticism and part descriptive essay, this nonfiction collection likewise exists as many things at once and navigates assorted perceptions, politics, history, literature, cultures, and pop culture of the Midwest.

One such exploration is Christman’s analysis of averageness and normalcy often considered to characterize the region. An essay reads, “Midwestern averageness, whatever form it may take, has consequences for the entire world: what we make here sets the world’s template.” These attributes quickly become problematic in society and also personally. Social and race issues ranging from colonialization to working-class challenges form a significant part of the Midwest’s history:

The idea of Midwesterners as normal underlies the idea of Midwesterners as egalitarians. If you read books about Midwestern history, you’ll encounter the two words together almost incessantly. If, however, we take “egalitarianism” as an idea that is meant to cover all actually existing people -- and I take this to be the only meaningful form of egalitarianism -- it fails as a description of Midwestern political history. (Not that there are many places it does describe.)

What makes Christman’s book brisk and thought-provoking is how, in that same section, he also goes on to make references to horror and science fiction, discussing the area’s duality with “nostalgic tropes” contrasted by an evil side in fiction, film, and television shows such as In Cold Blood set in Kansas and Stranger Things in Indiana.

Reading Christman’s book is like a road trip through time and sentiment and culture of the Midwest, and he depicts traveling through the area as “that unnameable melancholy one feels on Midwestern road trips, driving through those towns that seem mirror-images of one’s own: I have always been here; I have never been here; I will never be here again.”

Christman is a lecturer at the University of Michigan and editor of the Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing. He reads at Literati Bookstore on Wednesday, April 8, at 7 pm, which is the day after Midwest Futures is released April 7. I interviewed him about what the Midwest is and how he wrote his book.

Q: When did you start researching and writing about the Midwest? How did you become interested in it?

A: Probably the first trigger was reading Marilynne Robinson’s essays and fiction in my 20s. I don’t remember ever thinking about the Midwest as a “thing” before I got into her, even though I had grown up here and lived here most of my life. Inspired by her, I did a seminar paper on Midwestern literature in grad school in like 2006, and then I didn’t think much more about it until my wife and I moved here in 2010, and she started trying to parse the cultural differences between Southerners and Midwesterners -- she’s a Texan. The thing that she kept coming up against was our vagueness. We seemed unable to describe ourselves except in the most generalized, imprecise, cliché terms: “Oh, we’re just pretty ordinary people”; “Oh, it’s just like anywhere else.” Not descriptions but anti-descriptions. When you find that your brain is full of language that renders you unable to narrate something that’s a part of your lifelong daily experience, there’s probably a story behind that inability, right? That’s always worth looking into.

Q: You live in Ann Arbor and are a lecturer at the University of Michigan. Tell us about your connection to this place and the Midwest.

A: I grew up in Alma, Michigan, which is only a few hours away from where I live now, and in terms of social distance, it feels like another country. The highest-achieving kids I went to high school with -- I was not one of these kids -- aspired to go to college at places like U of M, or maybe Oberlin. Whereas the kids I teach now, at U of M, a lot of them also applied to places like Harvard and Yale, places I don’t remember even my smartest friends aspiring to. This wasn’t because they were less smart; it has more to do with feeling impossibly far from centers of real social and economic power, feeling that these places are not for you.

Alma was a thriving country town in the very early 20th century, experienced a downturn after World War I, and has kind of struggled ever since, especially post-NAFTA, as I learned during the course of my research for this book. While I was in high school, we lost several of the major local employers, one after another. I got out and went to college in Grand Rapids [Calvin University]. After college, I lived in the Twin Cities for a year and a half and did my MA at Marquette University in Milwaukee, so the five years I spent in the South getting my MFA in creative writing at the University of South Carolina-Columbia, and then teaching at North Carolina Central University, were really a weird interregnum in a life of mostly unbroken Midwesternness.

We came back here in 2013 because my wife, Dr. Ashley Lucas, got a tenure-track job at U of M, where she teaches theater and helps run the Prison Creative Arts Project. I teach mostly first-year English and sometimes intro creative writing, and also a class on the writing process. It is the best day job I could ever hope to have, and returning to the Midwest definitely felt like coming home: “Ah! A place where it is cold and people never hug each other! At last, I feel safe!”

Q: What do you tell people when they ask you what the Midwest is in conversation?

A: It depends what mood I’m in: “According to the Census Bureau, it’s these 12 states.” “It’s a badly formulated concept that keeps changing definition because its role keeps changing vis-a-vis the rest of the country.” “Not Texas.”

Q: Midwest Futures is organized in 36 short essays that appear in six “rows” like the square mile survey plots that were drawn when the Midwest was a territory. Since there are many ways to view and understand the area, how did you decide on this organizational scheme? Why plots instead of, say, bodies of water or people?

A: Two reasons. One, I am an obsessive researcher and fiddler, and I will keep messing with things and restarting things forever unless I give myself little ways of knowing “This is done.”

A story I always tell my students, because it’s illustrative and helpful, is of the time somebody asked James Joyce why he adopted so many weird constraints while he was writing Ulysses: 24 books, each corresponding to a book of the Odyssey and a house of the Zodiac and I forget what all else, each written in a different mode, etc. The guy expected Joyce to give some esoteric answer about how crucial all these parallels were to the meaning of the book. Instead, Joyce looked at him like he was stupid and said, “It was a method of working!” For some of us, writing is itself so potentially endless that you just need these signposts.

And two, the grid thing just kept coming up and coming up in my research. Michael Martone has a brilliant essay about it, “The Flatness.” It seemed like a clear, workable design for a book that, in its first draft, badly needed structure.

Q: The last essay covers a range of topics, as they all do, including climate change, industrial issues, and possible futures. What do you speculate is next for the Midwest?

A: I mean, survivalists, futurists, and land speculators definitely seem to be very interested in the “vast interior region” of the U.S. A couple years ago, tech blogs were trying to promote it as “Silicon Valley 2.0.” It’s a place that’s relatively free from, say, earthquakes; it has a lot of unused “human capital” -- terrifying phrase; it’s got comparatively good -- if, in many places, aging -- physical and institutional infrastructure for transport, production, education, and so many other things; it has fertile farmland, for now, though industrial agriculture generally seems like it’s afflicted with the death drive. So the Midwest is a place that is attractive to a lot of people trying to promote very different kinds of futures, once again.

The future I want to promote is one in which we -- humans, Americans, Midwesterners -- respond to the unprecedented threat of climate change by trying to show solidarity with each other, to live as though my fulfillment depends on the fulfillment of the other. That last phrase is the great Marxist literary critic Terry Eagleton’s attempt at updating Jesus’ “Do unto others as you’d have others do unto you.” It turns out Jesus is an even better aphorist than Terry Eagleton.

So that would mean, for example, resisting any politics that rejects immigrants or refugees -- people who, in the coming decades, will often be fleeing climate disasters that this country did more than any other to create. It would mean rejecting any politics that propose some particular group of people as “OK to exploit” because of their inherent lesser worth.

How I promote that world depends on the year and the situation and my capacity. In 2014 to 2017, I did it by getting really involved in running a literary magazine for prison writers, The Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing. I’m still involved, but it just dominated my life for a few years.

In 2018, I threw myself into my union’s -- ultimately successful -- contract campaign, which redistributed not only money, but in some very real ways, some power downward at the University of Michigan. They now know that we can still mount a credible strike threat.

This year I’ve done it by donating to and canvassing and making calls -- only a few; I am a severe telephone-phobe -- for Bernie Sanders, whose positions on environmental issues and prison issues are the most radical in the race.

I always try to do it in my writing and teaching, though I also pursue those activities for their own sake. I try to do it in my daily life and how I treat people. Mostly I fail at it because, like all humans, I’m a mess. That’s why we need to have solidarity.

Q: In the acknowledgments, you mention that your job as lecturer at the university allowed you the support and schedule to be able to write. What was your writing process for Midwest Futures?

A: It was first an essay for Hedgehog Review, which I worked on passively -- reading a lot and jotting down occasional notes -- during the spring of 2017, and then I worked on it very aggressively once school was out -- all-day writing sessions, etc. -- and filed it in July, I think. That was the first essay that my friend Barbara McClay ever commissioned from me -- she is both a great editor and possibly the most talented writer I know. She made it a lot better. The essay was published in November of that year and went mildly viral, and I thought there was more there, so I started putting together a book proposal the following summer.

Note: Book proposals are awful. They’re basically like writing an incredibly detailed outline, and I’m not an outliner. I figure out what I’m going to write by trying to actually write it. So doing a proposal made me feel like I was writing most of a book just to get someone to pay me money to write a book.

Then, midway through the summer of 2018, Anne from Belt Publishing reached out about having me do something for them, and at some point during our phone conversation, she used the words, “I don’t think it’s necessary for you to do a book proposal,” and I almost blurted out “I love you,” which would have been awkward. It was just such a relief to hear. I signed a contract with Belt and then spent the fall of 2018 being too busy to write the book, because of work, volunteer commitments, freelance assignments that I probably shouldn’t have taken, exhaustion, etc. This built up a strong feeling of panic that carried me through several weeks of long writing sessions in January and February of 2019. My classes were all bunched at the end of the day, so I could wake up, put in six or seven hours, and then go teach. I don’t recommend this as a lifestyle.

I turned the book in in March, worked on other things, and then radically revised it during the summer, in between trips to deal with family medical emergencies on both sides of our marriage: my mom; her dad. The 1,000-word six by six grid thing was what I settled on during this phase to keep me focused and to help me know when I was done with each part.

Q: How have you gone about learning and reading about the Midwest? Do you have favorite sources of research and writing on the Midwest?

A: This is actually a good moment for Midwestern studies, insofar as any academic subfield that isn’t STEM-related can even have a “good moment” right now. I went to the Midwestern History Association’s conference in 2018, and it was an intellectually alive place. Belt specializes in the Midwest, and I have appreciated the work of my fellow Belt authors, including Rachael Anne Jolie, whose Rust Belt Femme comes out right before my book does.

I’ve appreciated Jon Lauck’s books and scholarly anthologies. So many books came out just during the last five to 10 years that were incredibly useful to me in writing this one, or at least that I enjoyed reading a lot: David Treuer’s Heartbeat of Wounded Knee, Tiya Miles’ The Dawn of Detroit, Kristin Hoganson’s The Heartland, Meghan O’Gieblyn’s Interior States, William Hogeland’s Autumn of the Black Snake, Greg Grandin’s Fordlandia and The End of the Myth, Dan Egan’s The Death and Life of the Great Lakes, Sarah Smarsh’s Heartland, Herb Boyd’s Black Detroit.

Even since I finished the book, there have been things I wish had published sooner or that I’d known about them sooner, because I think the book would have been better if I’d grappled with them, like Nick Estes’ book about the Dakota Access Pipeline protests, Our History Is the Future.

When I research something, I’ll grab the books that seem like the obvious starting places and then go crazy digging through their footnotes to find older sources. But I’ll also look at reading lists that scholars or others have compiled online and kind of move through those at random. At one point during my research, I found a bibliography that was literally called Midwest Environmental History Bibliography, so shout-out to that person, because that pointed me to some pretty important articles.

I read or tried to read all the foundational books on the Midwest or Midwest-specific topics by William Cronon and Richard White, James Shortridge and Meridel LeSueur, Mari Sandoz and Marguerite Young. I write this way not to be name-droppy but because I want readers to get a sense of how fertile this field is! It’s probably not what I’ll do, but a person absolutely could lead a very fulfilling intellectual life just focusing on Midwest stuff.

When I research something, I also sometimes do the equivalent of just throwing paint at the wall: I’ll find the section of the library devoted to it and just grab everything that looks vaguely interesting, whether it seems related or not. So this is how I would stumble on books that turned out to have insights that I really needed, like Kenneth Kusmar’s argument, in a book on the ghettoization of African-Americans in Cleveland, that mass adoption of cars led to a rezoning of cities, which in turn gave northern segregationists the opening they needed to confine black people more than had previously been the case. He also pointed me to the incredibly inspiring fact that when the militant abolitionist/national hero John Brown was on the run in 1859, he lived openly in Cleveland, supported by a coalition of black and white abolitionists. This is precisely what Marilynne Robinson has been trying to say about Midwestern cities and towns, that many of them were once home to a prophetic moral impulse that drove people to do deeply brave things, and that our belief in the Midwest’s everydayness or dullness is among the things that prevent us from recovering this spirit.

Q: What are you reading now?

A: I’m now going to be doing a book-review column for Plough Quarterly, so I’m trying to catch up on good new books and reissues for that. I’m reading the Library of America’s new anthology of ‘60s science fiction for that right now. For fun, I’m reading John Crowley’s fantasy novel Aegypt, Jane McAlevey’s No Shortcuts about labor organizing, and L.M. Sacasas’ The Frailest Thing, a collection of articles about the way technology shapes us.

Q: Will you continue to study the Midwest? What are you working on now that this book is done?

A: Well, the publicity cycle on this book is just starting, so I suspect I won’t really know what I’m doing next for a while. My head has never really been cleared of this first book. But because talking about potential books is much more fun than doing them, I’ll say that some books I’m thinking of writing next include:

-- an essay collection centered on the idea of “being normal” -- a theme in Midwest Futures

-- a short, readable, one-volume history of world literature, aimed at normal people; this one would obviously take me several years to research, but it’s something that would be fun and I can see the need in my own classroom

-- a historical novel about the New Hollywood of the 1970s and its sudden end

I keep buying new books about the Midwest even though I’m not sure if I’ll ever do anything with them besides read them. There are topics I get burned out on but inevitably come back to later, and the Midwest seems to be one of them. So we’ll see.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Phil Christman reads from "Midwestern Futures" at Literati Bookstore on Wednesday, April 8, at 7 pm. You can pre-order the book from Belt Publishing.