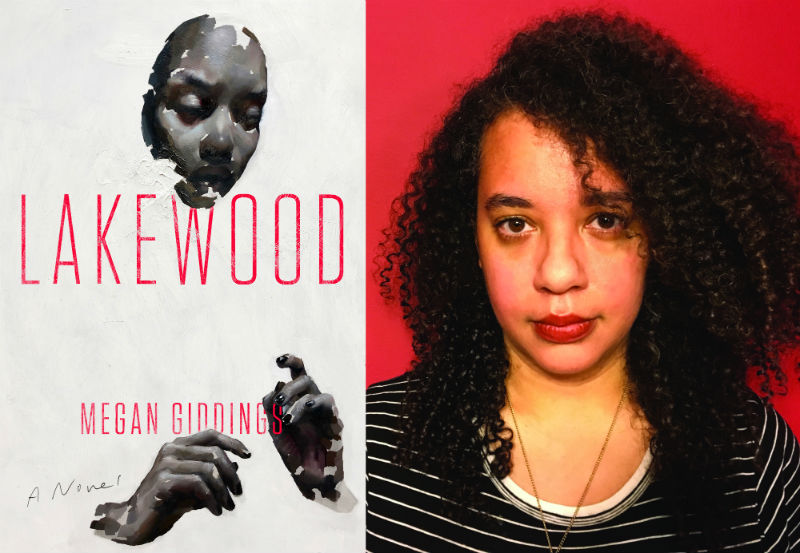

Megan Giddings' debut novel investigates what's really going on in a research study in a small Michigan town

The town of Lakewood, where you don’t know what’s part of a research study and what’s separate or real life, provides the setting for a new book of the same name by Megan Giddings, a University of Michigan graduate. This shifting ground calls into question what is true in the experiences of the main character, Lena Johnson, who moves to Lakewood for the promise of good pay and health insurance (albeit as a subject in the research study). A dystopian novel apt for the times, Lakewood moves quickly and constantly probes what lines people will hold or cross for the sake of science or their family.

Early on, Lena mulls over a foretelling comment by another character:

To make life easier, we have to agree there is no such thing as normal, the doctor had said while typing on her laptop. If you think too much about how things should be, you forget how they are.

As the novel unfolds and Lena joins the study, supposedly on memory and funded by the government, she has to grapple with whether the increasing physical and mental side effects of the tests are worth it. She furthermore undergoes surveillance, notices that the town is predominately white while research subjects are black, and must endure extreme circumstances, including taking unidentified medications. Whether Lena will forge ahead with participating and if the purpose or outcome of the research will be revealed become the questions that propel the novel.

Giddings was scheduled to speak Wednesday, April 1, at Literati Bookstore, and the event was canceled owing to COVID-19. I interviewed her by email as planned prior to the pandemic.

Q: How did you come up with the idea for Lakewood?

A: One of the most frustrating things for me as a writer is I can rarely tell you what I’m talking about until I’ve finished a few drafts. The book began being about a strange town where things are not like they seem. And it’s a kind of game I play regularly when I’m driving through small towns. I love these picturebox towns you can drive through in the Midwest -- I grew up in one -- and you can think the best and worst of times are all happening on this one very cute block.

It’s also in some ways about my own experiences with healthcare in this country. A member of my family had a health scare. It took all of our savings to find out that he was fine. In the weeks between the potential diagnosis, the tests, and the MRI, we had so many conversations about what we would have to do if the diagnosis was confirmed. Where would we get the money to keep him alive? And this was with insurance. And while I’m still angry about this experience, on a much greater scale, this is something Americans have to face every day. I’ve said this throughout promoting Lakewood when the question comes up, and I’m even angrier about it now (I did not expect to somehow get angrier about this!), but it is inhumane to not have affordable and easily accessible healthcare.

Q: Many instances of racism appear in this novel, including medical experimentation on African-Americans. In a letter to a friend, Lena writes:

The man said he had heard stories since he was a boy: You don’t ever go to the basement of the old hospital. He said colored people were always coming and going. The woman said Colored? in an I-beg-your-pardon way. It made me like her. I always like anyone who hears something racist and can immediately react ….

What inspired you to write about this? How do you see horror and racism interacting in Lakewood?

A: There’s this trope that happens in the beginning of a lot of thrillers or horror movies. A person, usually a woman, sees something strange that immediately puts her on high alert. Someone -- a well-meaning friend, the dweeb she’s currently dating, a distracted parent -- tells her that she’s imagining things or being too sensitive or that she’s just being anxious in some way. And for me and a lot of BIPOC I know, it’s kind of a similar thing. Unless, it’s an egregious incident, a lot of white people when hearing or experiencing an example of systemic racism or seeing what are often called “microaggressions” will still question it: Are you sure? Why would someone do that? Aren’t you overreacting? It doesn’t seem as big as you’re making it …. I think it was easy to write about some of these experiences because, well, there is that direct analogue.

I do want to say that I did bristle a little at this question -- while there are moments of racism in my book, I think any book that takes place in a densely populated area where there are many different kinds of people and the only people who are fully developed characters are white and who don’t have to think about money is also saying something about racism and class. It’s one of those things to consider: who gets to have these things only be a subtext in their work and who are the writers expected to make these things text and talk about them regularly.

Also, I do want to be clear, my reaction isn’t whoa, this is a racist question. It’s more of a general reaction because of the way that books by writers of color get talked about as being about race, while books by white writers often engage in othering and race-adjacent language (whiteness as a default while everyone else gets explicitly raced, an all-white cast in New York City, etc.). I did write a book about race and class and inequity. I knew I would be talking about these things.

But I think that any writer who is writing "realism" (although we could probably have a long conversation now about what that even means!) and is writing about the United States is writing about issues of race and class and gender. The foundation of our country is built on ideals and big ideas, but it was also built upon by these things. I do think people, but writers especially should consider why the people who tend to profit off these inequities (gender, race, class) don't get asked about these issues while the people who do have to contend more with these issues do often get asked to talk often about them.

Q: As Lena spends more time at her “new job” in Lakewood, strange occurrences cast doubt on what is true and what is contrived. Any of Lena’s perceptions and the information given to her by the people running the research study could be faulty. Truth, lies, and blurred lines between them create an unnerving atmosphere, and Lena finds searches about sensitive topics are blocked on her phone. Does this uncertainty connect to today’s technological advances and social norms in which we can get an abundance of information yet have to sift through it to determine what’s real?

A: It does tie into this. I started writing this book in 2014 and did a final edit with my editor in 2019. One of the things that is so wild about being alive right now is seeing how different reality seems to be for people based upon your relationship with the internet. The news you get, the language you use, even sometimes the way you perceive yourself, is shaped by your relationships with social networks.

Mixed in with that is grief and anxiety. I think grief and anxiety create uncertainty and blur the lines of reality in ways that people seem to not fully understand until they’re a step away from a situation. I think about the times in my life where I’ve been grieving or attempting to manage anxiety (I’m saying this as if I’m not in the middle of one of these moments with COVID-19, but I know I’m there), and every interaction I have with someone has a different charge than when I’m feeling neutral. I’m hoping Lakewood captured some of that feeling.

Q: The novel starts out in third person and changes to first person in letters that Lena writes to her friend in Part 2. How did this switch help tell the story?

A: I think it was important for the last parts of this novel that a reader felt closest to Lena even when she was feeling the most distant from herself and her life. During revisions, the feedback I kept getting from readers is they wanted to make sure that during all the strange events, all the ideas, all the complications, that there was still a heart to this story. Having the novel switch hopefully reaffirmed that even though these interesting and scary and wild things are happening, the most important thing in this book is Lena.

Q: You thank Indiana University’s MFA program for support in writing Lakewood. What was your path to and through an MFA program like

A: My path to the MFA is I applied right out of undergraduate and was rejected from everywhere. So, I started working. My job had no relationship to writing or literature; I worked with technology. And my job was very time-intensive and draining, so I rarely wrote anything for a few years. I would read; I would journal. And then I started writing short stories. Eventually, after doing an MA, I ended up at Indiana University in their MFA program. I started Lakewood there.

Indiana is also the place where I learned that being a writer isn’t about writing every day. The instructors who made a huge impact on me -- Elizabeth Eslami, Romayne Rubinas Dorsey, Cathy Bowman, Ross Gay -- are because they emphasized how much of the writing life is about building a healthy relationship to creativity. It’s reading, it’s mentorship, it’s friendship, it’s service, it’s creating not for the recognition (although that’s nice!) but because the work itself is important.

Q: Prior to that experience, what did you study at the University of Michigan? Tell us about your time in Ann Arbor.

A: I studied creative writing and literature at the Residential College. At the time I wanted to be a poet, and my primary teacher was Ken Mikolowski. He taught me how to write not to impress or talk at other people, but to think about writing as a conversation between you and the reader. I still often think of Ann Arbor as home. I lived there for years after I graduated, I worked at the university as a staff member, and I met my husband in Ann Arbor. It’s a place where I learned how to be a reader and a writer, to start thinking about how to build communities, and where I ate very well. There are things I don’t miss -- the cost of living! -- but it’s a place I’ll always love because it’s where I truly began to become the person I am today.

Q: As features editor at The Rumpus and fiction editor at The Offing, what do you look for in writing? What advice do you find yourself giving often?

A: The two magazines are very different. The Offing is committed to centering marginalized voices and/or modes of writing. So, I’m looking for stories there that can balance style with substance. At The Rumpus, I’m editing nonfiction for a wide audience.

Maybe the only advice I give when I’m editing with writers that overlaps is to be more vulnerable. A thought a lot of readers have is, why is this story being told? Why is this person telling the story? For a lot of things -- although there is no one size fits all advice for writing -- one of the easiest approaches is to make that clear, and that does mean being maybe more open than you have to be in real life.

Q: What’s next on your list to read and recommend right now?

A: Some forthcoming books in 2020 that I’ve read and loved are Days of Distraction by Alexandra Chang, How Much of These Hills Is Gold by C Pam Zhang, and Crooked Hallelujah by Kelli Jo Ford. I’m currently reading Indelicacy by Amina Cain.

Q: What’s next on the horizon for you?

A: Writing-wise, I’m working on what is hopefully my next book. In general though, like I hope everyone else, staying home.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.