Diane Cook's novel "The New Wilderness" envisions a world after extreme climate change

Imagine being dropped off in the wilderness, uninhabited except for 19 people with you and rangers who patrol the land. Modern amenities are nonexistent, but the upside is that the air quality is much better than the polluted city. You live nomadically and hunt, fish, and gather to survive. This is not an extended camping trip. It is your new way of life.

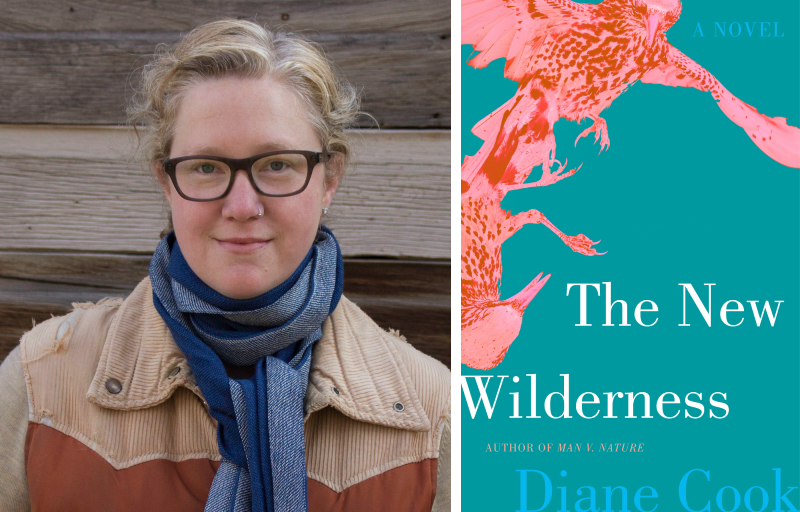

This intense scenario forms the premise of Diane Cook’s new book, The New Wilderness, a speculative novel involving relationships and the environment—and how the latter influences the former. The novel has landed on the long list for the Booker Prize. Cook has taught for the University of Michigan, is a U-M alum, and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

In a joint virtual event, both Cook and Karolina Waclawiak, whose new novel Life Events was just published, will read and discuss their new books through the At Home with Literati series Monday, August 31, at 7 pm.

The characters of The New Wilderness, including Agnes, her mother Bea, and her mother’s husband Glen, go to the wilderness as part of a research experiment to determine whether this lifestyle is sustainable. Bea joined to save Agnes’ life. Agnes was five years old when they arrived and gravely ill from the effects of pollution. Despite learning how to stay alive in the wild and improving Agnes’ health, the characters’ memories of their former life, their love for one another in all its forms, and the burden of subsisting clash and inform their individual choices.

Early on, Bea’s concerns emerge when considering their next journey to a ranger post farther than they’ve had to go before:

Glen hooked his arm around her neck and pulled her close. “Now, now,” he murmured. “This will be fun.”

She knew that a big part of Glen believed this. But no part of Bea did. She pictured the map in her head again and saw all that unknown land, that beige parchment, all that nothing. They would be changed on the other side of it, that much she knew. Not knowing how was only one of the things that scared her.

The New Wilderness calls into question what the natural world is and should be, while also showing how vast the wilderness within and between people can be.

I interviewed Cook about this book and her writing.

Q: You have been a radio producer for This American Life and taught in a literature program the University of Michigan. Tell us how you came to be a writer.

A: I’ve always loved writing, but I never thought it was something you could do as a job or make a career from. So that lead me to teaching at places like the New England Literature Program (NELP), and to making radio and to This American Life where I was an editor and producer. After a few years there, I realized I was working with people who had made writing their career. I was feeling I needed a change, so I left the radio show and went to graduate school for writing. I wanted to give myself a chance to really finish a book, so I didn’t jump into a permanent full-time job after I graduated. And I’ve managed to write and publish and teach as my career ever since.

Q: You mention visiting places and researching for The New Wilderness in your land acknowledgement and author’s note. The novel feels very physical and rooted in nature. How did the natural world inspire you for this novel?

A: I really wanted to write a book about nature as much as it was about characters or events. I love reading about nature. I might even spend more time reading nature writing than novels, to be honest. But I don’t want to be a nature writer. I am definitely called to fiction. I want to make stuff up and build worlds. I think there are things I can explore only through fiction. With fiction I feel truly free. But the natural world has always been a lens I see the rest of the world through, and the more I read and learn about it the more that is the case.

Q: The premise of leaving the city for the wilderness owing to smog and pollution feels more and more plausible as climate change expands. This novel could be anywhere since places are named “the City” and “the Wilderness State,” which makes the book as alarming as it is fascinating. Were you imagining a worst-case scenario with the environment?

A: Yes, I was imaging the novel taking place after the most calamitous effects of climate change had already been absorbed, dealt with, and normalized. If I drew a straight line from today toward the future, past the point of no return, this is the world I could envision. I never imagined we would destroy the world and the human race. Rather life would look very different, though not unrecognizable, and a lot of things that seem unfathomable to us now would become the new normal. That was one of the big parts of building the world for me and starting the novel in the time I did. I didn’t want to write a disaster book. I wanted to write about surviving after the disaster. What would that look like?

Q: As mother and daughter, Agnes and Bea have both a loving and an anguished relationship. Agnes struggles to understand Bea’s choices for their survival, such as her interactions with Carl. Despite how the quest to survive would seemingly bring people together, they maintain their individual perspectives, which color their view of what the others do. It seems that love and the best intentions cannot overcome distrust. Was it hard to write about their relationship?

A: Writing about their relationship felt good. I want to say it felt cathartic, but then that makes it seem I was working something out through them. I love their relationship because it felt true. Watching their relationship be complicated, watching them want something they struggled to achieve made me feel like my difficult relationships aren’t deep personal failures. Relationships are hard, especially elemental ones like mothers and daughters. They felt authentic because when they failed, they tried again. They were a bit haunted by each other, and that felt right to me. Their love was true, too. I don’t think you can have such anguish without big love. And so it was really rewarding to let them be flawed humans full of love and confusion.

Q: As I was reading, I considered two possible endings for the book, and I was surprised and delighted when it was wholly different from the options I had pictured. I am always curious whether an author knows what the conclusion will be or writes their way there. What was your approach to the end of The New Wilderness?

A: For the first time in my writing life, I used an outline for this novel. I had to. It was too big a story with too many parts. The trick for me was giving myself an end point but allowing myself to be enticed and surprised by other paths, small side trails that would still bring me to where I thought the story needed to go. I won’t give anything away, but I knew the characters would have to end up where they ended up. That was a big part of the idea of the book and of the experiment they are living.

Q: This book is debuting in the midst of a pandemic. Are you doing anything differently with your novel than your earlier short story collection as a result of publishing in unique times?

A: My book tour sure looks different! I click join on Zoom, see some familiar faces or their names in a chat box. The conversation is still fun, though, and the reading is probably shorter (attention spans online are even shorter than in person), but then we all click “Leave” and we’re alone in our rooms. It’s weird and a little sad. But then again, a friend living in the Netherlands attended my reading in Connecticut the other day. And all my East coast friends with children attended my West Coast readings because the time difference allowed them to put their kids to bed, pour a drink, and hang out online for a little while. So there are definitely pros to the online book tour. But nothing can take the place of traveling to a town where I know I’ll see the faces of old friends in the audience, and we’ll all go get a drink after and catch up. In this time especially, losing that intimacy and connection is especially hard.

Q: What are you reading and recommending these days?

A: I loved Temporary by Hilary Leichter and A Children’s Bible by Lydia Millet most recently. I think everyone should read The Grapes of Wrath, again if you’ve already read it. No matter when I read it, it feels relevant and radical. The world it shows is sadly familiar. I always highly recommend The World Without Us by Alan Weisman. I’m really looking forward to reading Desert Notebooks by Ben Ehrenreich and Empire of Wild by Cherie Dimaline.

Q: While this question is now more challenging because our lives have been upended by COVID-19, and you may or may not be working on it as planned, I would still like to ask: what’s next now that The New Wilderness has been published?

A: I’ll be working on adapting The New Wilderness for television. This was always an idea I had while writing the book, and so in April, I started talking with people about optioning the book. It was a weird time because the industry had basically shut down, and there were a lot of unknowns. But apparently in the time of COVID-19, a show that could potentially be filmed outside with a very small and consistent cast is a plus. As far as next book projects go, I don’t know yet, but I might be writing a book about—gasp—a city!

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Diane Cook will read from The New Wilderness in a virtual event through the At Home with Literati series Monday, August 31, at 7 pm.