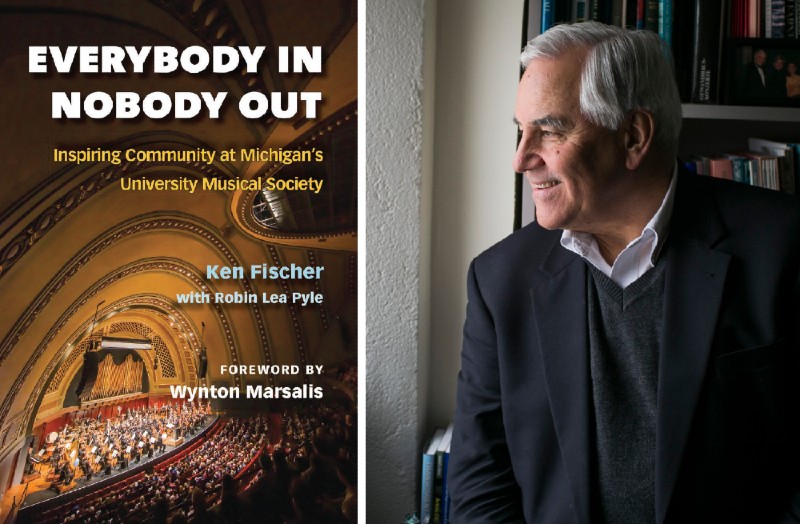

Ken Fischer makes the case for collaboration and connectivity in his book "Everybody In, Nobody Out"

This post contains two sections: a book review and a brief interview with Ken Fischer.

On June 1, 1987, Ken Fischer became the sixth president of the University Musical Society at the University of Michigan.

That date marks the beginning of 30 years of transformation, innovation, and collaboration.

Fischer’s Everybody In, Nobody Out: Inspiring Community at Michigan’s University Musical Society written with Robin Lea Pyle is a book of many parts. It is a memoir, an insider’s view of some of the leading performance artists who come each year to Ann Arbor and, perhaps most important, a guide on how to operate a non-profit by reaching out to and connecting with the community at large.

The title comes from Patrick Hayes, a mentor to Fischer and former head of the Washington Performing Arts Society. Hayes had developed a policy for art presentation that emphasized inclusion at every level. His policy was "Everybody In, Nobody Out" and it became Ken Fischer’s mantra.

“It was about making connections and forming partnerships for everyone’s enrichment,” Fischer writes. “The great thing about collaboration was that it could be the foundation of everything we needed to do as an organization: secure outside sources of funding, raise our visibility in the community, expand our audience, gain new insights, and build enthusiasm for working on new projects.”

Fischer’s book is a short history of those collaborations with the university, with world-class performers, with other local arts groups, and with local and national businesses and philanthropists.

But first a prelude.

Fischer writes about his idyllic boyhood growing up in Plymouth, Mich. His parents loved music and encouraged their four children to learn how to play piano. In time, Fischer and his two brothers each chose other instruments. Fischer began playing cornet and taking private lessons from U-M music professors. For several summers he was enrolled in the National Music Camp at Interlochen where he had successfully switched from cornet to French horn. At Interlochen he would meet a flutist, Penny Peterson, who would one day become his wife and have her own successful career as a performer and educator. After graduating from the College of Wooster, Fischer started graduate school at the University of Michigan, where he also became involved in protests against the war in Vietnam and racial discrimination.

His interest in pursuing a doctorate in higher education led to a staff position in Washington, D.C., on President Nixon’s Commission on Campus Unrest. It was in Washington that Fischer became involved in experiences crucial to his later success at UMS. He worked for educational organizations setting up conferences, planning programs that moved away from dry lectures and toward more interaction. He continued his love of music and his French horn playing with a group of friends and took advantage of Washington’s lively art scene.

In 1982, his older brother Jerry was a co-presenter for a presentation by the King’s Singers, an a capella sextet from Britain, at Detroit’s Orchestra Hall. Fischer decided to arrange a performance for the group in Washington at the Kennedy Center. This effort began his work as a performing arts presenter and, also, a long relationship with the popular King’s Singers. It also provided a number of obstacles that would forge the base of Fischer’s approach to operating a successful performing arts series.

He learned about reaching out to the community. He made an arrangement with a local barbershop chorus. They would sell tickets for a share of the revenue that they would use to pay for expenses for a barbershoppers’ convention. The group was also helpful in connecting Fischer with a local radio station to play some of the King’s Singers recordings.

Despite his experiences with music and organizing events, Fischer was still unsure about stepping into the role of leader at the UMS. The organization had a solid history of presenting top classical music performers. It was respected, but it had also become a bit stodgy.

“UMS had always played it quite safe by sticking mostly to the classical music canon, presenting renowned orchestras, recitalists, chamber ensembles and our own Choral Union,” he writes. “Also as a matter of tradition, the organization was very much of top-down work culture.”

Fischer saw an opportunity to build on what had come before. He, his wife, and his son, Matthew, had enjoyed life in the national capital but were ready to come home to Michigan.

Fischer would move toward a more democratic work environment, allotting more freedom to his staff. He also began to develop a stronger relationship with the university, with other performing arts presenting organizations and with artists’ representatives.

His first challenge was working with the schedule he had inherited and hosting one of the most famous names in classical music, composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein with the Vienna Philharmonic. He was also keen to arrange for Bernstein to come again the next year, 1988, which would mark Bernstein’s 70th birthday and the 75th anniversary of U-M’s premier performing venue, Hill Auditorium.

After a successful concert, Fischer made his pitch, to which Bernstein responded, “I love this town, I love the people of this town and I love this hall. We’ll be back.”

Ann Arbor would be one of only four venues hosting the Bernstein birthday tour. Fischer began building those relationships with donors to help meet the cost of having the Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic return. He also worked on getting U-M students involved by offering discounted tickets. He involved Pioneer High School orchestra members with an opportunity to meet members of the Vienna Philharmonic in advance of the Pioneer orchestra’s summer trip to Vienna. A post-concert gathering at the home of U-M president James Duderstadt brought Bernstein and a group of university music students and a select group of students who were in line for tickets for a late-night conversation.

These collaborations with businesses, workshops for university students, and involvement in the wide community were hallmarks of Fischer’s time at UMS. He was a man about town with a mission. He was a promoter for the UMS but also others, including regular attendance at the fall and spring fundraisers of local NPR stations WUOM and WEMU. He would use that radio time to regale audiences with stories about the visiting artists to the UMS series.

Over time Fischer built on UMS’ reputation as a premier traditional classic music presenter, but he also took the series in new directions as it began to be a major presenter of experimental music, jazz and world music, classic and modern dance, and world-class theater, beginning with two plays from the Stratford Festival in 1993, two plays from the Shaw Festival in 1994, and a breakthrough collaboration with The Royal Shakespeare Company in 2001. The RSC worked with popular U-M professor Ralph Williams on developing their production of the Henry VI cycle of three plays.

Fischer also brought racial and ethnic diversity to the mix of music and theater.

All of these presentations required working together with the performers, local businesses, the university, students, and patrons to go beyond just the performances and making art and community come together.

Fischer includes many backstage stories about Andre Previn, Cecilia Bartoli, Jessye Norman, Jean-Pierre Rampal, Yo-Yo Ma, and others. For local readers, the book also contains the names of many local businesses as well as arts and educational leaders.

The forward was written by Wynton Marsalis, the jazz and classical trumpet virtuoso and director of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

Marsalis has performed at UMS programs for a record 19 times.

He sums up some of Fischer’s assets.

“Guided by a love of community, Ken’s countless presentations have demonstrated not only respect for what his audience wanted but a deeper commitment to what they needed,” Marsalis writes. “He possessed a belief in his own good taste and very strong constitution to withstand democratic dialogue. Ken was and remains the definition of an arts rebel, fighting a guerilla war from the inside.”

In September 2014, President Barack Obama presented Fischer on behalf of UMS the 2014 National Medal of the Arts, the nation’s highest public artistic honor.

Fischer retired as UMS president on June 30, 2017.

*****

When Ken Fischer retired as president of the University Musical Society in 2017, he was already warned that he would be in demand by local organizations to lend his expertise to local organizations. Friends told him to learn not to say “yes” to everything.

But Fischer had two projects he couldn’t resist. He was asked by Ismael Ahmed, founder of the Concert of Colors, to become chair of a new Concert of Colors Advisory Board. The Concert of Colors has a mission “to bring together the diverse peoples of Southeast Michigan to share their cultures, music and traditions in an atmosphere of celebration, respect and acceptance.”

Fischer also has teamed up with the group that helped launch his career as a performing arts presenter. Fischer was asked to be volunteer president of King’s Singers Global Foundation, which works to commission musical works, support teaching, and cultural collaboration.

“I am doing a number of things, including teaching arts leadership [remotely] at the University of Michigan School of Music, Theatre and Dance,” Fischer said in a phone interview.

In addition to that, he said, he’s caught the volunteer bug and has been working with Big Brothers and Big Sisters and doing some speaking engagements.

One thing he has avoided doing is interfering with the work of his successor Matthew VanBesian.

“I couldn’t be more happy with what Matthew and his team have been doing. They've shown creative imagination and found ways to celebrates artists and the arts,” Fischer said

These have been difficult months for UMS and other arts organizations but Fischer remains optimistic.

“In the arts, we pride ourselves on our creativity,” he said. “Where there is a crisis, there is opportunity. They have to be optimistic and deal with the hand they’re dealt.”

He said Zoom wasn’t “everyone’s cup of tea” but when we can’t gather in large groups, it’s been helpful.

As a French horn player, he’s been tuning in Berlin Philharmonic horn player Sarah Willis’ Horn Hangout. He praised the work of Joseph Haj, the director of Minneapolis’ Guthrie Theatre for its programs in a time when they can’t perform as usual.

Arts groups face financial problems, but Fischer said that patrons, performers, businesses, and government will be there to help.

Fischer had special praise for Tom and Debby McMullen. When Tom McMullen sold his business, he donated money for the next five years to UMS, he purchased 1,000 copies of Fischer’s books to raise money for UMS. Fischer said he has been signing and delivering books to subscribers.

During his tenure as president of the University Musical Society, Ann Arbor played host to the most acclaimed classical, jazz, and world music ensembles and recitalists. Fischer said he once asked Berlin Philharmonic president and string bass player Peter Riegelbauer what he thought attracted these performers to return time and again to the UMS and Ann Arbor.

“He identified five things that made UMS standout,” Fischer said.

First, Abbado, said they loved coming to Hill Auditorium. Second, Fischer said Abbado praised the sophistication of the UMS audience. Where some big-city concert series were reluctant to play certain challenging music, the orchestras could be assured that Ann Arbor would embrace a performance of a work by Arnold Schoenberg.

“Third, he looked out into the audience and saw students everywhere,” Fischer said.

Fourth, though Ann Arbor is a small city, it has a high quality of hospitality.

“And fifth, the quality of our care we showed their ill conductor Claudio Abbado,” Fischer said.

Hugh Gallagher has written theater and film reviews over a 40-year newspaper career and was most recently the managing editor of the Observer & Eccentric Newspapers in suburban Detroit.

"Everybody In, Nobody Out: Inspiring Community at Michigan’s University Musical Society" by Ken Fischer with Robin Lea Pyle (University of Michigan Press, $29.95). A portion of the proceeds go to the University Musical Society. John U. Bacon hosts a virtual book launch and interview with Fischer on Tuesday, September 22 at 7:30 pm at ums.org. Back in July, Fischer talked to UMS about his book; you can read the interview here.