EMU professor Christine Hume's "Saturation Project" offers a lyric memoir composed of three essays

Three essays fill Saturation Project, a new book by Christine Hume, a professor at Eastern Michigan University. Described as a lyric memoir, the text obliquely depicts various moments, ranging from Hume’s childhood to interactions with her daughter.

In the first essay, “Atalanta,” first-person accounts about personal thoughts, family, and a daughter intermingle with Greek mythology and examinations of feral kids raised by bears. Wanderings in the woods and through memories merge with ancient stories and animals in such a way that the distinctions between them blur, as Hume elaborates:

I read the story of Atalanta as if I were swallowing it, but it swallows me. Then I tell it to my daughter because I don’t have a childhood I can tell her about yet. I steal Atalanta’s, which is like mine in that the most longed for moments are inaudible.

It’s as if the essays are a way of remembering, but recollections are transposed, taking inspiration from other places.

Later, the essay asks, “Name a child who never made animal noises, who never pretended to be a dog in the kitchen, or a horse in a field, a terrible tiger or a tender one.” There, what is pretend, real, myth, or memory becomes nebulous through the generalizations and behavior in which one creature is another. Yet, we also learn, “A girl grows up how she grows up. You might dream it this way or you might prove it. You might believe in your own survival.” Ultimately she grows up. Perhaps the overlap between stories and life is a way of enduring.

Then the second essay, “Hum,” delves into the sound of humming. From singing to oneself for keeping pace while swimming to “electricity buzzing all around us,” this piece finds the noise in unexpected places and behaviors. The sounds may be unintentional, menacing, or something else. Hume illuminates how she understands sound with this question: “Was there a time when I didn’t know language as disguise, as mass hysteria aping comprehension, a growl impersonating a purr?” This essay, too, remembers, and it also explores various encounters and views of the humming, given that it directly tells the reader that, “By inviting you to listen, I’m trying to script your interpretation of my hum, and to flip my own.” We learn what her hum can be through the essay’s depiction.

A final essay, “Ventifacts,” turns to the wind. Wind and weather. Wind carrying radiation. Wind affecting a family picture. Wind gods. Wind rustling through corn. Wind impregnating mares and fertilizing plants. Wind farm. All of these places and situations where the wind arises may be understood as the wind shaping things. The essay reveals early on that “a ventifact is a ‘wind artifact,’” and so perhaps each section within the essay is itself a ventifact. The presence of wind becomes frequent and unavoidable, and we may begin to wonder as the essay does, “Didn’t we all used to be like the wind, pure and strong, stroking the strings of imagination, blowing open vowels through a flute?” The essay allures the reader with this idea.

Hume has previously published poetry and turned to nonfiction in recent years. I interviewed her shortly after Saturation Project was published in January.

Q: You’ve lived in numerous places around the United States and Europe, and now you’ve been in Michigan for nearly 20 years. Tell us about what keeps you here and what work you do.

A: I marvel at my staying power! Before moving to Michigan in 2001, I had never lived in one place more than four years. Since birth, I’ve spent 2-3 years in one place then moved on. The pattern was somewhat hard to break, and it conditioned me to feel at home in alienation. Perhaps it is also why I don’t have many memories of my girlhood; all that moving around was disruptive, and I found that psychologically it was best to make a clean break each time. What keeps me here is that I love my job and my community. This is my 20th year teaching at EMU in the English Department—a very supportive environment with fantastic students and a lively Creative Writing program. I still travel a lot (as we are 20 minutes from a major airport), but maybe when we are no longer in a global pandemic, that urgent shot of the urban or any kind of otherness will feel less necessary!

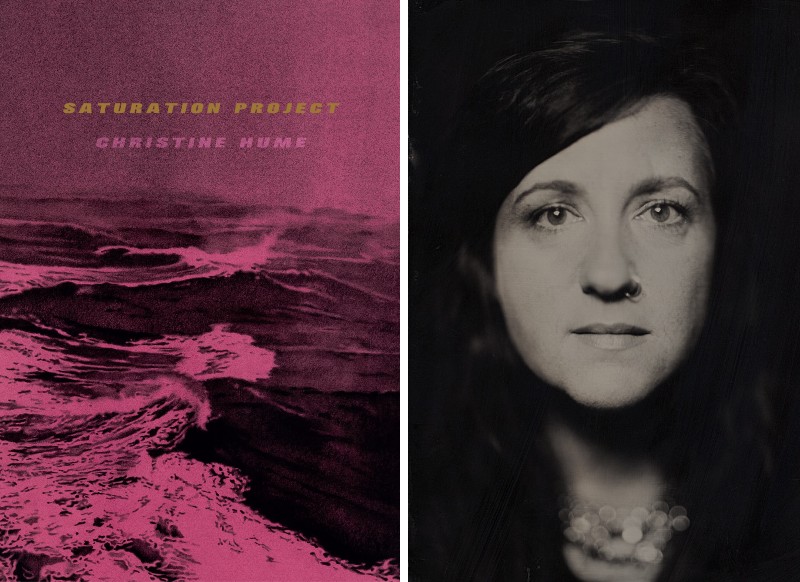

Q: Saturation Project came out this month. The book itself shimmers with a silver cover and gold end pages under the jacket. While authors tend not to have a say over the book design, I was curious if you had any input on it. Is it everything that you pictured?

A: I’m glad you noticed! I love it. Lucky for me, I live with the world’s best and sexiest book designer, Crisis Studio (Jeff Clark), and my very generous press, Solid Objects, let him design the book. I picked the cover art, by the fabulous Andy Mister, but Crisis actually introduced me to his work. Several years ago, we went together to an exhibition of his work in NYC. I didn’t have a design in mind, but it was somewhat of a collaborative process in that I saw each cover and font idea in real-time. “This one or that one,” he’d say. We’d talk about it. I might change my mind, or ask a question, but ultimately, I trusted Crisis, and Jeff Clark is entirely responsible for the book’s gorgeous state of solid objectness.

Q: While I imagine authors get tired of this question, it’s fascinating for readers. What inspired the title of Saturation Project?

A: Actually, no one has asked me this question yet! I’m glad you have, though, because the word “saturation” atomizes several ideas central to the book for me. For one, saturation’s link with color is vital. The color red saturates the first essay especially; red is the mood and the very subject in some ways. And if you think about saturation as the degree to which one thing is dissolved into another, I’ve tried to describe identity formation as a kind of saturation. Maybe what we think of as a “self” is a saturation of sensation and experience, of the merging of myth and memory into language. Though each essay invests in a different optical framework, the book’s guiding metaphor is the saturated physical self that cannot be contained or emptied. I wanted to make sure readers understood that the book is not so much about an experience as much as it is an experience in and of itself. That is the project, to create an immersive experience of visceral thinking through narrative. What I mean by “visceral thinking” is thinking that comes from somatic experience, thinking that is not distinct from feeling, thinking that isn’t merely “rational and abstract,” but connected to our bodily life. Some kinds of knowledge, for instance, are accessible only through experience.

As if you needed yet another: I also think of the book as the project of saturation in terms of genre: it is prose is saturated with poetry or more precisely, an essay saturated with poetic approaches to language.

Q: Speaking of genre, Saturation Project is a lyric memoir. How do you describe “lyric memoir” to people who will read your book and be unfamiliar with the form?

A: It’s a memoir written by someone who has mostly been engaged with poetry for the past 35 years. I have also called it an experimental memoir, a girlhood triptych, and three interlinked essays. My concerns are not the traditional concerns of a memoir. Because I wanted to animate parts of experience that evade determination, the book veers into lyric intensities and away from novelistic linear time and redemption.

Q: What inspired you to make the switch from poetry to essays?

A: I’ve thought a lot about this, but I still don’t have a completely satisfactory answer. I can tell you that as the circumstances of my life radically shifted with becoming a parent, I became obsessed with the generous capacities of the sentence (life sentence?) as well as enamored with information, our wild guesses at knowledge. Poetry conditioned my way of using language in order to access whole worlds of nuanced interiority and relation that I might never have known. But communicating via poetry is like knowing a language that isn’t available to non-poets, and I wanted to see if I could bring that operative insight with me into paragraphs and story.

Q: Let’s keep talking about sentences and structure. The first two essays in Saturation Project contain sections that are mostly a paragraph long and separated by section marks. In the last essay, each section is again primarily a paragraph, at rare times several, but the sections are instead separated by page breaks. How did you land on these forms for your essays?

A: Through a lot of trial and error! I hope the space, the openness of the form, activates the reader’s imagination, seduces the reader into pursuing connections and thinking alongside the text.

Q: Next, I’d like to ask you a question about each one of the three essays. Let’s start with the first one. “Atalanta” blends myth with first-person memories in nature and with animals. At one point, it talks about how, “Instead of a stuffed bear, my daughter wants a story she can hold….” What compelled you to bring together your life and that of your daughter with stories of bears and other animals? How did you first get interested in mythology?

A: I am interested in girlhood as both a category and a bodily experience that is lost as soon as it is lived and also monstrously multiple. I wanted to represent it as a subjectivity outside of subjugation. I wanted to represent my girlhood feeling, but I look back into an abyss, as if I were a totally different person then. On the surface, my life is rich in plot—I can recite the places I’ve lived, the violent freedoms and freewheeling neglects of a childhood in the '70s and '80s—but I don’t have a lot of retrievable memories. I have often wondered at my amnesia of my own girlhood—is it because I moved around so much as a kid? Is it because of my relentless pursuit of the future? Is it trauma-induced? Does girlhood live outside of language or in excess of it?

Q: So many questions to explore! Turning to “Hum,” sound is associated with personal experiences, erotic scenes, Zug Island in Detroit, and consumerism, among other things. You write, “To write my surname, I first must write ‘hum.’” Yet we learn early on that humming was happening on walks earlier at a young age. Was your surname an inspiration or an afterthought? Did you start seeking out different hums?

A: Seems obvious now, but I only realized the link between “hum” and “Hume” well into writing this essay. After typing “Hum,” my middle left finger would automatically reach for the “e” on my keyboard. That’s kinetic memory in action! As a sonic phenomenon, however, “Hume” is somewhere between “hue” than “hum.”

An aside: the first assignment I give students in my Sound Poetry class is to write a poem entirely with the letters of their first and last name. They each use their own personal shrunken alphabet. We have a special relationship with these letters and sounds, which are usually the first letters we learn to write, and a special relationship with their sounds, oriented as we are to hearing our own names. This assignment is almost categorically met with resistance but also yields some of the most powerful, psychologically compelling work.

Q: That sounds like a fun and hard assignment. Finally for the last essay, “Ventifacts” was published on its own previously. Does anything change in its appearance in Saturation Project? How did you go about paying attention to the wind for this essay?

A: Though the opening and closing are very similar, everything else has changed—it’s expanded, radically edited, rearranged, and more fully resonant with the other two essays. The idea was to bring my girlhood hum and my daughter’s colicky screaming into the same lineage.

Q: And what are you reading and recommending these days?

A: Two books that I’ve just finished reading simultaneously, and which I whole-heartedly recommend, are Lisa Robertson’s The Baudelaire Fractal and Elena Ferrante’s The Lying Life of Adults. Both portray the ferociousness of girlhood. Speaking of which, I just finished editing a special issue of the American Book Review on girlhood, featuring some amazing reviews of terrific books. Coming out mid-February.

Q: So, you’ve written both poetry and nonfiction. Looking ahead, what are you writing next?

A: This book took almost four years to come out after I found a publisher. Because of that, I have another book manuscript, an essay collection, finished, which just landed me an agent. I am also working on two others right now. Both take documentary approaches—artistic points of view combined with fieldwork, reflection, and analysis—and both are collaborations, which have been lifelines in the isolation of the pandemic. You can find excerpts from All the Women I Know, a collaboration with the photographer, Laura Larson, that archives women in the act of resistance, at Tupelo Quarterly and the Seneca Review this spring. The other collaboration is a young adult version of Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, which we are writing with research and artwork from our teenaged daughters. All are written in prose, and though each project embraces a distinctive relation to nonfiction, I’m calling them all essays.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.