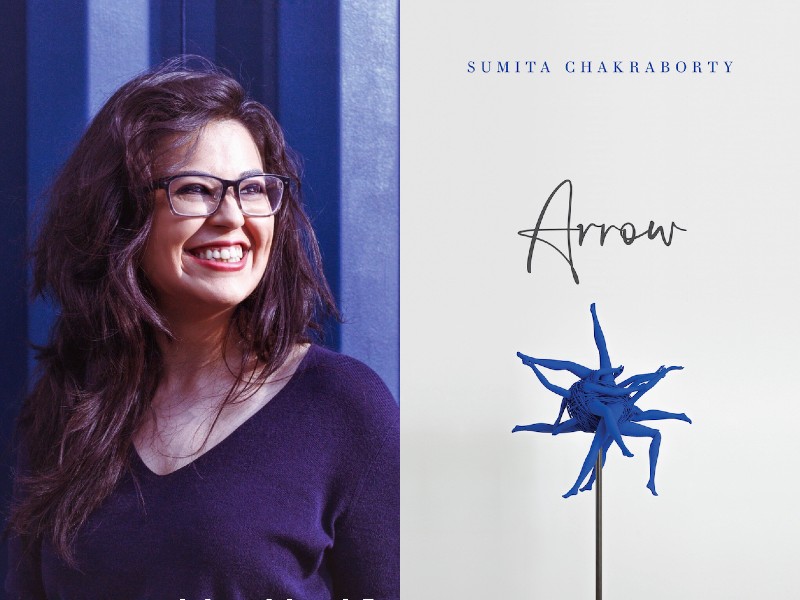

U-M Zell visiting prof Sumita Chakraborty’s "Arrow" displays the poet's exploration of words' contradictory meanings

Going into reading Sumita Chakraborty’s debut poetry collection, Arrow, it’s not a secret that the book follows traumatic experiences. As she describes in “Sumita Chakraborty on writing Arrow,” which was shared with me by the publisher, Alice James Books:

Much of this book resides in a range of aftermaths: in the aftermath of the severe and prolonged domestic violence I experienced as a child and adolescent; in the aftermath of sexual violence; in the aftermath of my sister’s death; in the aftermath of breakups; in the griefs and anxieties that follow in the aftermaths of unending sociopolitical events; in the aftermath of unending ecological devastations.

Knowing this informs but does not explain the poems in Arrow, but it sets the stage for the intense emotions and scenes depicted in them.

In “Most of the Children Who Lived in This House Are Dead. As a Child I Lived Here. Therefore I Am Dead.” that appears early in the collection, the reader learns from the poet that:

[…] my earliest affections for abstraction were by

way of disguise, that my turn next to straightforwardness was by way of

retaliation, and that I will always negotiate between the two like a brown,

black-haired Goldilocks, perpetually dissatisfied with the size of the

offering, although now, I tend to think of obstruction and clarity alike as

acts of definition.

These lines serve as a clue to reading these poems, and they also put the reader on unstable footing. Is a line straightforward, or is it an abstraction? There is no way to know, and yet readers must ask themselves whether a line means what it says or something else. You could question that about all poetry, yet in the case of Arrow, it becomes a way of reading what may at times seem fragmented but nevertheless connects.

“Some of my favorite words mean wildly contrary things," Chakraborty says. "Such is true of shift, which means, among other things, beginning and last resort.” Other relationships read like aphorisms to mull over, such as in the final poem, “O,” which says, “A bird is to its throat as a promise is / to its sharp edge.” That’s one of many lines that lingers long after reading.

Another way that these myriad meanings surface is in a series of poems titled as essays. In “Essay on Devotion,” the argument feels like a series of conditional if-this-then-that statements on the poet’s relationship to poetry by exploring other lines of poetry, from which the poet concludes “that it is not possible for a poem to exist, and that to read a poem is to embark on a mission that bears no bloom.” Despite such challenges of poetry, this book does bloom.

The title Arrow itself is an exercise in meaning. The penultimate poem reads:

Arrow, though I believe you to be a tool of devotion, I am drawn most to the shadow

your figure impresses on my brutalities, like how the word for your home describes me when I wait,

discomfited, unable to sit still, secretly running my tongue along my sharp and crooked teeth.

This book both explores the violence and death that arrows can cause and considers what direction to go next, like in the way that arrows can point.

Chakraborty teaches at the University of Michigan as the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Poetry. I interviewed her about her new book by email.

Q: Tell us how you came to be living in Ann Arbor and working at the University of Michigan. What’s unique about life here in contrast to other places where you’ve lived?

A: I began the position of the Helen Zell Visiting Professor in Poetry here at the University of Michigan in August 2019, after seven years in Atlanta (I got my PhD at Emory and taught there for a year after that). Before that, I was in Boston, and I’m from Massachusetts so I’d been in the New England area for pretty much my entire life. Boston and Atlanta are wildly different, but I love them both. I confess that my sense of Ann Arbor has been pretty impacted by the pandemic—at this point, I’ve spent the majority of my time here quarantined! But I’ve enjoyed what I’ve gotten to know, and it’s great to be around snow again. Winter has always been my favorite season.

Q: Arrow is your first book. What surprised you about the writing and/or publication processes?

A: Well, there weren’t too many surprises in some ways—while Arrow is my first book, I’ve been doing literary work for a while, including working on the editorial side, and I wrote and rewrote Arrow several times, during the course of which I had the opportunity to hear more of how the sausage is made publication-wise from friends and colleagues. I was pretty patient and deliberate about the publication process, so I feel like I didn’t really kick that off until I felt like I felt on solid ground about not only the manuscript but also the next steps. I think that most of my surprises have been COVID-related, since the thing I didn’t plan for or anticipate was launching my debut virtually!

Q: So many unexpected things with COVID! Turning to talk about Arrow specifically, lines in Arrow’s poems explore the sometimes contradictory or varied meanings of words. When did you become interested in the ways that words express one thing and also another?

A: Thanks so much for noticing that—it’s definitely a primary interest of mine. Not only do words often express two contradictory or at least differing things, but they also often express a whole host of incidental histories, feelings, ideas, emotions, relationships ... if you take the full etymological view of words especially, each word is its own constellation or even its own galaxy. I think my interest here is at least partially influenced by the way in which literary scholarship and creative writing are intertwined for me—I got the bug for them both at the same time in college, and since then I can’t really imagine either part of my mind without the other. What drew me to reading and writing in the first place was this sense of multiplicity that lives in every unit of language, which strikes me as a remarkable source of freedom, of danger, of invention, of risk, of malleability, and of precision all in one.

Q: That quality of language is fascinating. Let’s also talk about the subject matter of your book. Arrow reports on death, grief, love, Earth, flight, mountains, windows, ash, stars, and figures from Greek mythology, among many other things. How did this range of topics come together for you in this collection?

A: Well, the most fundamental story I wanted to tell in Arrow was that of the experience of living in the aftermath of severe domestic violence, other entangled forms of assault, and grief (in my case, particularly for my sister, who died in 2014 at the age of 24). This idea of an “aftermath” is complicated by the fact that there is no “after” violence or grief, especially when one thinks about how those things reverberate through the entirety of a life. The fallacy of “after” becomes even more true when one considers the various scales on which devastation and mourning take place—not only for one singular person, but for entire communities, for other people, for other communities, for other species, for planets, for ecosystems, across history, and so on. That being said, I did also want to take the idea of “after” seriously, because the main autobiographical story that this collection tells is of my experience becoming able to embrace love, joy, care, and kinship—even when all of those things were weaponized against me or foreclosed for most of my formative years. This tension forms the tightrope that is Arrow’s throughline, and all of the other obsessions and preoccupations—including the figures and tropes you’re picking up on here—in the collection are lassoed to it, collide with it, or orbit around it.

I wouldn’t say any one of those things you’ve plucked out are a “topic” in and of themselves, although I’m definitely obsessed with some of them as topics in their own right. That said, I think every single one of them picks up importance in the collection through the way that they both structure and create the scale of any given moment or any given poem. And additionally, I think I was really invested in creating a world in this book that is as full as I perceive the world to be in actuality.

Q: I’d like to ask about the horses that appear in your poems, such as in “Marigolds” where a line asks to “Summon a thousand wilding mares,” or in the poem “Dear, beloved” which says, “Lunar maria means moon seas, but when I hear it / I picture horses, torqued female beasts who live on the moon.” The horses feel simultaneously powerful, destructive, and protective. Why did you include these horses in your poems?

A: You know, I’ve never thought of the horses in isolation like that! I’m glad they resonate with the trifecta of power, destruction, and protection—that particular triangulation is a huge obsession of Arrow’s, and in a way, one of my goals was for every single metaphor or figure in the book to speak in some way to it.

I hope I don’t disappoint by saying that there isn’t much of a unified theory of horses there, at least not one I was conscious of constructing—in the case of the horses in “Marigolds,” I was thinking of the iconography of wild horses in the West and of the immensity of what a horse stampede might feel like, and in the case of the horses in “Dear, beloved,” when I hear the phrase lunar maria, I really do picture horses, likely due to the similarity between the words maria and mare. The names of the horses in “Dear, beloved” came from horses I saw in a riding competition of some kind—I can’t remember what kind! I know nothing about anything pertaining to horses or riding in the material world. A friend from grad school did, though, and participated in competitions, and she took me with her to one during the period of time during which I was most immediately mourning my sister and writing “Dear, beloved.” I nabbed the horses’ names directly from that outing.

There’s also the fact that “Marigolds” and “Dear, beloved” are deeply connected, with “Marigolds” ending with my sister’s death and “Dear, beloved” dilating on it—I value building interconnections linguistically in moments where there are interconnections thematically, which likely also has to do with the fact that they emerge in both places.

Beyond that, while I’m sure there’s much more that could be said about each and both, I think any given reader’s individual interpretation likely matters more than anything I might offer!

Q: Let’s keep talking about the poem “Dear, beloved.” It has been mentioned frequently in reviews and praise, which I noticed after writing my opening to our interview and these interview questions, so I added in this question. How did you go about composing this single-spaced, 11-page poem?

A: Brick by brick! I always knew it was going to be a very large single stanza, like a huge monument, or the monolith from 2001, or a huge rectangular grave, etc. I’d just write into it steadily, adding lines, deleting them when they didn’t go anywhere interesting, trying another train of thought from that point of origin, over and over, until I felt like I had a complete draft. When I did, I went back through again to figure out what needed to be cut and what needed to be in a different spot, and what transitions were missing. I think it took about a year and a half or two years or so.

Q: Related to what you touched on earlier, the short piece, “Sumita Chakraborty on writing Arrow,” that your publisher sent with the book mentions that this collection involves the aftermath of “unending ecological devastations,” among other things. I noticed how oceans, mountains, and trees, among other aspects of nature, weave throughout the poems. How do you see Arrow as commenting on ecological devastations specifically?

A: It all goes back to the problem of scale. And this is something about which I write in my scholarly work, too. The book is primarily about being an adult in the aftermath of domestic violence and other forms of assault during childhood, but that’s far from the only scale of violence in the world, including those that affect me and the people that I love. Ecological devastation is one of them, both due to its imbrication with racial, gendered, ableist, and class-based violence and due to its implications for ecosystems and for the planet. There’s no story of violence that doesn’t include ecological devastation in my view, and while the often-chaotic landscapes in Arrow speak to the speaker’s emotional and psychological upheavals and arcs, they also speak to ecological destruction in and of itself, because there is no more chaotic landscape than the ones in which we currently live. (A friend of mine recently tweeted four pictures of 2020-2021 natural disasters and failures of government/infrastructure in the face of various natural events, accompanied by the remark about how the Anthropocene is apparently being directed by Stanley Kubrick. I’m writing this answer with that tweet in mind, as well as with the devastation unfolding in Texas on my mind, which is happening as I answer.) Beyond that, I hope Arrow also makes the point that I don’t think there’s any way to separate “the human world” from “the natural world”: there’s no “nature poem” and “sister poem,” for example. They’re both the same poem.

Q: You were poetry editor at AGNI. How long were you there? Did that work change how you think about poetry? Why or why not?

A: I worked at AGNI for 13 years, first as an editorial assistant while I was in college, then as assistant poetry editor, then as poetry editor. I would say that the biggest way that experience affected how I think about poetry is that in many ways it was my introduction to contemporary poetry—reading submissions and corresponding with accepted poets was a crash course in all that was out there, which was infinitely valuable for me since I didn’t know I was interested in literature broadly until about a year into college. It was great to be able to learn that there’s a vibrant world of living writers at around the same time that I was learning that there are vibrant worlds of dead writers. Beyond that, and especially as time went on and my position at the magazine changed, I think working on the editorial side taught me a great deal about the logistics of publication as well as the kind of work it takes, and the kind of work I want to do, to help create a literary world that celebrates the values, perspectives, ethics, and voices that I hold most dear and that I feel are most urgent in and beyond literature.

I’m committed to highlighting texts that remake received narratives on any scale, from the most microcosmic scale of a single person experiencing a single emotion to the most macrocosmic scale of communities and collectives grappling with systemic abuse. I became deeply committed to the idea that editorial work is, for me, an act of service, which means that when I do it, I want to explicitly ask who and what my work is serving. Paradoxically, that led to my stepping down from my role at AGNI (and my role as art editor at At Length, which I held for about three years as well); currently, my main editorial commitment is as a volunteer reader for the Michigan Review of Prisoner Creative Writing. That’s not to say that more mainstream literary journals like AGNI and At Length don’t entail massive acts of service—they very much do, and the current teams at both journals and many others show exactly that with every piece they publish! But I wanted to take stock of what I personally was using that energy to do, and I think that if I were to return to editorial work for a more traditional literary journal (as I occasionally do now, for example with my upcoming curation of the May 2021 installment of the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day series), I would wish to do so at a journal and in a role that would more explicitly foreground the idea of serving authors and texts that are actively engaged in this work of remaking.

Q: What are you reading these days?

A: Right now I’m pretty deep into research and writing for my scholarly book, so the vast majority of my current reading list is literary criticism and critical theory. In terms of new contemporary work, I’m slowly indulging in Alice Oswald’s Nobody, the new anthology Kink edited by R. O. Kwon and Garth Greenwell, and Ross Gay’s Be Holding.

Q: Acknowledging that the pandemic and current events are taking tolls on each of us in different ways, a bright spot can be looking ahead to the future. What’s next for you in your writing and teaching?

A: The big project right now is Grave Dangers: Death, Ethics, and Poetics in the Anthropocene, which is the scholarly book that I mentioned. I’ve been writing two series of new poems: one is a series of visual poems called “Image,” inspired by surgical photographs of my own hysterectomy, and the other is a series titled “The B-Sides of the Golden Records,” inspired by the question of what was left off of the 1977 NASA Golden Records. Handfuls of each of them have been published and are floating around here and there. More loosely, I’m also writing my way into questions that ended up out of the main frame of Arrow but are still related to similar topics (for example, questions surrounding my mother and the complexities of various forms of complicity with an abuser). Recently an idea for a book-length poem started poking at me, too. I tend to be a many-things-at-once kind of writer, and I always enjoy when I get to be in completely different headspaces in each genre, so as the academic book comes even more sharply into focus, I’m enjoying playing around and pushing my poems to take new shapes and take on new preoccupations without yet imposing too much of a plan on them. Just shaking some trees and seeing what falls out.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.