Caroline Kim's characters in "The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories" ask what is most important in life

A woman loses a child and yet she helps another, Suyon, pregnant with a baby rumored to not be by her husband, give birth. Then, with war breaking out in Korea, the woman meets an American, marries him, and moves to the United States. There, she finds herself engaging in animal husbandry and applies the same tactics she did with her acquaintance:

You get good at birthing horses and people send for you when they have difficult cases, mares too frightened and in pain to calm down, to do what is good for them.

You whisper the same nonsense you told Suyon: that they are beautiful and perfect and doing everything just right. Everyone, everything in the world loves them.

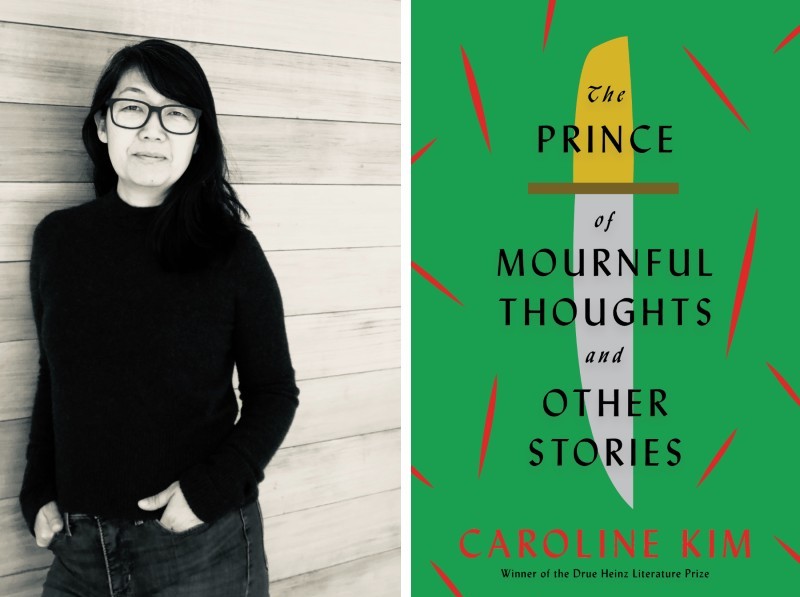

This woman’s dedication and strength to carry on through these significant changes in the short story “Arirang" attest to the resilient characters in The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories by Caroline Kim. It also shows how universal and necessary that encouragement and support can be, something we all need.

Kim’s stories in her new collection ask what is most important in life, with the options ranging from fortune or pride to family, truth, connection, and expressions of love. When a woman breaks down in “Magdalena,” a mother and daughter who attend the same church try to help, despite not wanting to be associated with her. They grapple with whether to address the woman’s dire situation or to judge the woman and try to distance themselves. As the mother tells her daughter about the woman:

“Those people,” she said, “they make life seem so hard. They make it seem impossible. But it’s not really. It doesn’t have to be. You do what you can and hope for the best. If you need to change something, change it. If you can’t, ignore it.”

Yet, the situation doesn’t quite let them ignore it, as many circumstances haunt characters in the collection.

In the first story called “Mr. Oh,” we hear from Mr. Oh himself, who asserts that, “I know it make no sense to look too much at history, but how else we going to understand self? We are—how you say—sum of decision we make. That who we real are. How we act mean who we are.” These sentences from this aging Korean laundromat owner are a way to see everyone in subsequent stories, to understand the uncertainty and pain that characters face and the paths forward that they nevertheless choose or create.

Kim earned her MFA in poetry from the University of Michigan and went on to get an MA in fiction at the University of Texas at Austin. She is now studying counseling in northern California, where she lives with her family. The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories won the Drue Heinz Literature Prize in 2020. I interviewed her about the book this month.

Q: What brought you to Ann Arbor for your MFA, and what took you away again?

A: A generous scholarship brought me to Ann Arbor for my MFA, and the freezing cold drove me away. Because I grew up in Massachusetts, I thought I knew what cold was, but then I learned that a Midwest cold is a completely different beast. I remember walking one night to The Blind Pig where a friend of mine (in the fiction program) worked as a bartender. I underestimated how cold it was, and by the time I was halfway there, I was moving slower and slower to the point that I was thinking very seriously that I might freeze on the spot. Faced with the dilemma that it would take me just as long to go back home as it would to continue to the bar, I kept going because at least warming drinks and friendly faces awaited me at the bar. Soon after I left Ann Arbor, I settled in Austin, Texas. I learned that I liked heat more than cold.

Q: Does it feel different to engage in your writing practice in different places, from Ann Arbor to Austin and now California? What changes and/or stays the same when writing from these distinct places?

A: My writing practice, which is erratic and changeable, isn’t much different from place to place, but I do find it easier to write about a place once I’m no longer living there. Mental distance and all that. Or maybe it has more to do with the passage of time. Probably both.

Q: In the recent virtual event for your book with Literati Bookstore, you discussed your switch from poetry, which you studied at the University of Michigan, to fiction. Could you elaborate here on what inspired you to make this switch? How did you go about it?

A: I started to suspect soon after I got to Ann Arbor that I was a fiction writer rather than a poet. The more I learned about poetry, the more I realized that questions of poetic form didn’t interest me as much as the stories and emotions in the poems. Not to say form isn’t important in short stories, too, but consciousness of form isn’t necessarily essential to the reading of it, whereas when one reads a poem, one must also reckon at the same time with the specific form or shape of the poem. Take line breaks for example—they inherently bring up questions of why here and not there?

Q: On that same topic, are there aspects of writing poetry that you now apply to fiction writing? Or vice versa?

A: Yes. I learned so much from writing, reading, and studying poetry. Things like how to compress time and distance, how to hone in on crucial details, how to cut, how to condense an experience to its essential features, complications, and consequences. While I still love reading poetry, I don’t write it anymore so I can’t say I bring anything to it from writing fiction.

Q: Let’s talk more about your new book. The stories in The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories include a variety of perspectives, like a business owner reflecting on his behavior and relationship to his wife. How did you channel these individual voices when writing these stories?

A: We hear most clearly the voices we have internalized, which is why I believe it’s generally easier for people of color to write as white people or women to write as men. A minority anywhere has to take in the language, attitude, and knowledge of the majority in order to survive, even if it’s only to reject it. Because I grew up in the Korean-American world created by my parents’ generation, I can still hear them pretty clearly. They, of course, never directly told me about their struggles, hopes, and fears, but by watching them carefully, I could intuit how they thought and what they cared about. At the same time, I also saw them as they were seen by the white dominant American culture—speaking broken English, standoffish or eager to please, unknowable, “inscrutable”—ultimately, not fully human, and that caused me a lot of pain. Erasure of one’s self or loved ones is an extremely painful mental state.

Q: Considering voices, The Prince of Mournful Thoughts' notes section mentions how the tale with the same name as your book was inspired by a true story in Korean history and literature. In the original story, you felt a connection to Lady Hong, wife of King Yongjo. Yet your tale is told from the perspective of a royal assistant. Why did you make that choice in your fictional account?

A: It was a choice I made out of necessity. At first, I tried to write the story from Lady Hong’s point of view but I quickly found that it was too limiting. In reality, they probably didn’t spend much time together, maybe only seeing each other at public events. Not only did they have different residences but Prince Sado would also have had a number of concubines to spend time with. So, if written in Lady Hong’s POV, most of it would be secondhand, and thus, weaker as a narrative. Only when I created the fictional character of the royal assistant did the writing of the story become possible. Now I had my fly on the wall, the character who could narrate, who could explain, who could hold and express the emotions created by the brutal events. Once he appeared, the story flowed very quickly.

Q: The story called “Arirang” covers so much ground, from the narrator’s first marriage in Korea to her second marriage and move to Montana. You’ve had your own reckoning with your heritage since you were born in Korea and came to the United States, as you write about in the book's notes: “About a decade and a half ago, I found myself going through a serious identity crisis. I kept wondering what my life would have been like had my family decided to stay in Korea. What would the Korean version of me be like?” Did writing about Korea and Koreans inform your answer to that question? If so, how?

A: No, not really. In the end, I don’t think those answers can really be answered, which is why we’re fascinated by them, why there are movies like Sliding Doors and the TV series Counterpart. We all make irrevocable decisions in our lives or have them made for us that make us wonder “what if.” But studying Korean history and language did help me feel more confident as a Korean person. It helped me to know myself better in a way that’s difficult for me to articulate. It’s a vulnerable feeling to know so little about where you come from, to be considered a representative of a country you are largely ignorant about.

Q: A passage from “Picasso’s Blue Period” has lodged itself in my mind. The narrator, who is awaiting the birth of a grandchild, ponders that “Americans find it easy to declare their love for each other. I love you, I love you, they all say but then manage to divorce each other several years later. I have never told my wife that I love her and I have never heard it from her. It is unnecessary. It would be like saying I breathe or I think or I live.” Characters love each other in their own ways throughout your collection. Tell us about how you see love threading through your book.

A: I’m most deeply moved by expressions of love that aren’t spoken: staying with someone because you know they need you, trying to lift burdens that haven’t been expressed, knowing of another’s needs and wants by watching them carefully, knowing them. In “Arirang,” the husband brings his wife a bowl of her favorite bean sprout soup after her miscarriage; in “Russell, Lucia, and Me,” Russell wants China to move away from their low-income apartment complex because he doesn’t want her to get stuck there; in “Picasso’s Blue Period,” it’s the narrator making the decision to have an abortion so his wife won’t have to. These thoughtful, unacknowledged actions are a much deeper form of love than direct expressions of it.

Q: Let’s also talk about “Therapy Robot,” the story that takes the form of journal entries by a mother who receives the TheraP150 robot for Christmas. This concept intrigues me because there’s the nightmare of technology eventually being able to read our minds, and the robot seems to be a step closer to that. You are in a graduate program for counseling. Did you write this story before starting your degree? What draws you to counseling?

A: I wrote this story in the first year of my counseling program when I was thinking about what people perceive therapy to be. Some people think it’s like paying someone to be a friend. And others think therapy is only about talking/revealing one’s “problems,” but as if it doesn’t matter whom one tells it to. If it truly doesn’t, then the logical result is that all we need is a robot. But actually, the most important aspect of therapy is the human connection part of it. What brings the healing about is the experience of feeling completely and wholly oneself in the presence of another human being in a supportive, safe environment. Can a friend or family member provide that? Absolutely. But unlike friends or family, who may bring their own baggage and history with the person into that space, a therapist can be more objective and focused on the individual. I’m drawn to counseling because it is a relationship in which healing can happen and is the primary objective.

Q: As we wrap up, what’s on your nightstand to read and recommend?

A: I’m finishing up a couple of books: Milk Blood Heat by Dantiel W. Montiz, which is amazing and rightfully getting a lot of attention. I’m also on the last book of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan series. I’m obsessed with her. I feel I’ve never read women on the page the way she writes them. It’s a revelation, and very exciting. Next up is Ha Seong-Nan’s Flowers of Mold and Bluebeard’s First Wife, both translated by the talented Janet Hong. I love that the number of works translated from Korean seems to grow every year. And I’m rereading Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous and Night Sky With Exit Wounds for a Pittsburgh Arts & Lecture event in which he’s appearing. I’ll be introducing him, one of the happy privileges of winning the Drue Heinz prize.

Q: Acknowledging that we’re about a year into a global pandemic and you’re in school, I’d still like to ask this: What’s next for you with your writing and/or otherwise?

A: I tried and failed to work on two different novels this year. I’m much further along on another collection of short stories, which I hope to finish by late summer. I’ve definitely felt more despair this pandemic year, experienced more days of not writing because I’m thinking why does it matter? But then again, I’ve read more this year than in the past 20, partly to lose myself in another reality, partly to remind myself pleasure exists. Now that I think of it, I suppose this answers my own question of why it matters. Stories matter a great deal, especially when we feel most hopeless.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.