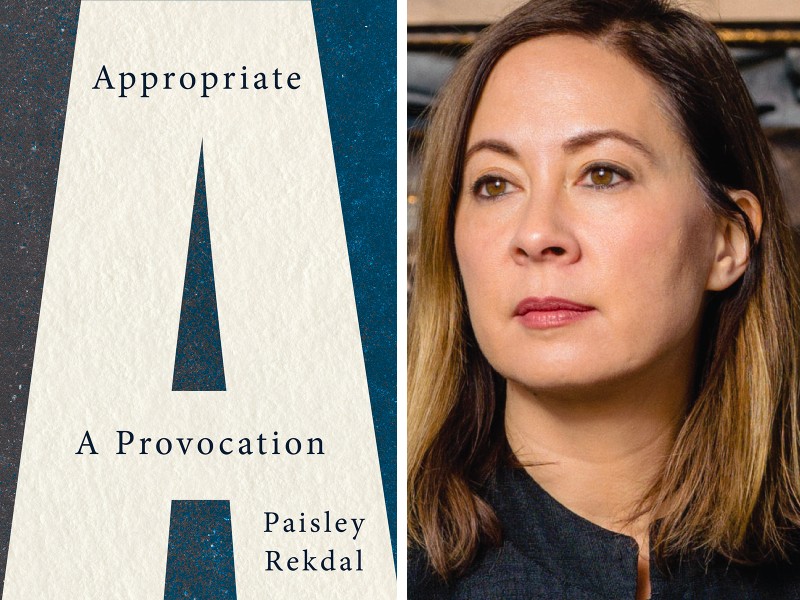

Utah poet laureate and U-M grad Paisley Rekdal considers the implications of cultural appropriation in literature in "Appropriate: A Provocation"

Paisley Rekdal examines cultural appropriation in literature in her new nonfiction book, Appropriate: A Provocation. However, this collection is not essays, as one might expect.

Instead, Appropriate consists of letters addressed to a student who is a new writer, and this structure offers a different, more conversational, and inquisitive tone. This recipient is not based on any specific person but inspired by many students and colleagues. The letters refer to the student as X.

Early on, the first letter defines the subject of cultural appropriation as being about identity. It is also, “an evolving conversation we must have around privilege and aesthetic fashion in literary practice.” Rekdal’s examples of the issue—both positive and negative, including hoaxes in which authors pretend to have another identity—demonstrate how important attention to the topic is.

Rekdal offers ways to understand, analyze, and navigate cultural appropriation. Rekdal asks many questions and also offers a list of them for evaluating one’s own work to let the reader consider what their answers are, too. She includes her own experiences from teaching, participating in conversations, and writing appropriative works herself.

You might be wondering whether cultural appropriation should just be off-limits, but Rekdal brings a more nuanced view, one that acknowledges some literature as effective and other literature as harmful. She writes to X, “When we write books that appropriate the experiences and identities of other people, X, we enter into the system in which we all participate but over which we individually have very little control.” This issue is so risky that Rekdal anticipates this question of “Do you opt-out?” The matter cannot be distilled so simply, though, because Rekdal offers instances when authors successfully write other identities than their own.

The question then becomes about what factors contribute to literature that engages in cultural appropriation working or not working. The answer changes, in part, based on the current moment in history and politics, notes Rekdal:

Nothing about our identities, our political presence, and social meaning in the world remains stable. So long as we change, the questions we hold around representation change with us, and what we take as fundamental aesthetic precepts now will be unfashionable, even embarrassing, to future generations.

Reading texts from other eras should consequently include reading them through the lens of the time in which they were created. Rekdal also suggests treating them as “cultural artifacts.” While an author of an earlier work may fail in some ways based on the present-day climate and values, the literature is a product of a different time. We can imagine that today’s literature can and will fail future tests of appropriateness.

Rekdal is a graduate of the University of Michigan’s MFA program and is now Utah’s poet laureate and a professor at the University of Utah. I interviewed her about her book and work as a poet laureate following her reading at the University of Michigan this fall.

Q: You were at the University of Michigan and now live and teach in Salt Lake City. Tell us about your time in Ann Arbor and what brought you to Utah.

A: I enjoyed my time in Ann Arbor while I was getting my MFA in Poetry from the University of Michigan. To be frank, it’s been so many years I don’t remember much about my time other than panic-reading books of poetry it seemed everyone but me had read and trudging through freezing slush to parties, but I do know that Michigan helped train me to be a better reader and writer. After Ann Arbor, I lived in a lot of different states and even countries, but I ended up in Utah when I got a job teaching at the University of Utah.

Q: Your new book, Appropriate: A Provocation, covers cultural appropriation. This topic has been prominent in the literary world, as illustrated by the examples you give from literary criticism, talks at conferences such as the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, and literature itself. For readers unfamiliar with this conversation, could you share a brief background about the discourse around cultural appropriation in literature?

A: To answer this question well would itself require a book (you can read mine!), but the basic argument around cultural appropriation in literature breaks down into two big questions or “camps” of thought:

1. Considering the pervasive, profound and historical effects of racism in our culture, writing in the voice or about the experience of someone outside our own racial and ethnic identity positions risks perpetuating stereotypes about those same identities, while also materially profiting from them in the literary marketplace

2. Writing outside our own identity positions is in fact the hallmark of literature itself and is not only a mark of the power of human imagination, but may also produce readerly empathy for those unlike ourselves.

The problem for me with both these positions is that they encourage people to treat the question of artistic appropriation as a “yes/no” proposition: either you can and should appropriate, or you can’t and should never try. The reality is that we are all engaged in acts of appropriation, and there are works of appropriative art that we not only accept but admire. So instead of having a “yes/no” debate, perhaps we should spend time talking about what specific appropriative works of art reveal about us as readers, what cultural desires and fantasies they suggest, and what works of art that “succeed” for us actually teach us about the complexities of race and identity.

Q: How did you get interested in writing about cultural appropriation?

A: An editor approached me and asked if I wanted to write the book based on a Facebook post I wrote about a poem and poet that had recently been called out on social media. Before that, I never considered writing such a book.

Q: You anticipate the reader’s question of whether someone should just not engage at all in cultural appropriation, and you go on to study examples. Considering an author, you ask, “Can she do it? Can she really pull that off? If she can, fantastic. If she can’t, well, why despise her for trying?” Do you get that question on whether to opt-out a lot?

A: I think most of the students I encounter today are so frightened by the idea of getting it wrong, they’d rather NEVER attempt to write about or in the voice of someone unlike them. I think many of them are looking for ways to avoid appropriation entirely. But the reality is that, as they continue on in their lives as writers, they will likely write a pantoum or adapt a fairy tale or engage in documentary work from oral history archives or write about the experiences of family members and other people they know: all of these are appropriative acts. We also all lead lives increasingly marked by diversity, so if people “write what they know” (a favorite workshop expression), eventually they will write about the diversity they experience, whether that’s a character who is neurodivergent or LGBTQIA or Black or mixed race.

Q: One of the letters asks, “In what ways can appropriation allow each of us to delve more honestly into the complexities that compose racial difference?” Do you believe that cultural appropriation can be productive?

A: I do, which surprises me. When I began writing the book, I thought appropriation was, at heart, always an act of exploitation. But then I started seeing writers and artists who appropriated other canonical texts and images in order to reframe people of color as the center—not the margin—of the original story. I began to realize that people can and have used appropriation to make their own communities part of the Western artistic tradition, to resist other kinds of institutions that would render them invisible. Appropriation doesn’t only work in one direction: people who have been historically marginalized appropriate as well, and have used appropriation to amplify their own beliefs, values, and art forms.

Q: We can see ourselves in literature, but it is not a full, true copy. You write, “… most literary characters are, even when complexly detailed, still sketches of humanity that resemble but never duplicate us.” The focus of your book is on writing, not as much reading, yet I believe readers can learn from your analysis of texts. How did writing this book change how you read and write?

A: It didn’t: the book performs how I read and write. That said, spending time trying to think through the ethics of appropriation did make me more considered in the ways I wrote some documentary poems about the transcontinental railroad. I was using oral histories for some poems, and I spent a lot more time considering the ethics of appropriation I would adhere to when responding to and utilizing these sources.

Q: The book’s format of letters to a student is compelling. Did you start writing the book from this perspective, or did you decide to make your essays into letters later in the writing process?

A: I felt instinctively that the book should be in letters, largely because the letter format allowed me to revise my opinions, to speak more casually at times, to question myself.

Q: What does being the poet laureate of Utah involve?

A: A surprising amount of “public” poems about events of note! I also created a web archive of Utah writers, past and present, called Mapping Literary Utah, and helped create a regular Utah Poetry Festival. Sadly, since the pandemic, I’ve led far fewer writing workshops with K-12 students, which were so much fun.

Q: What are you reading and recommending these days?

A: Reading lots of poetry and fiction. Three books that stand out: Burntcoat by Sarah Hall, which (though set in the pandemic) is really a book about women, art, bodies, and ambition; Intimacies by Katie Kitamura, which is a book about the surprising (and surprisingly uncomfortable) ways we become connected to each other; and The Silence That Remains by the Palestinian poet Ghassan Zaqtan.

Q: With this nonfiction book published, what’s next for you?

A: Finishing up two other books: a book of poetry called West: A Translation (you can see the digital version of it at westtrain.org) and a book on how to teach and read poetry.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.