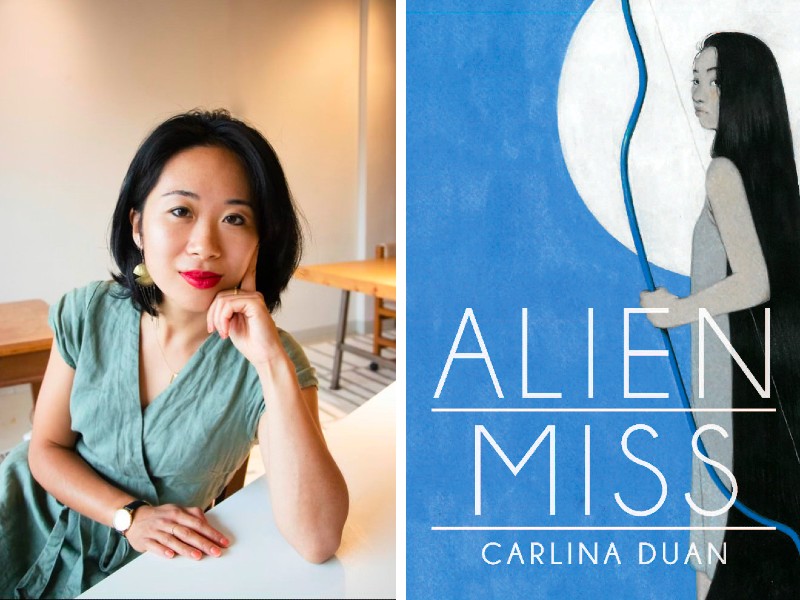

In "Alien Miss," Ann Arbor poet Carlina Duan explores the multiple identities Chinese Americans inhabit

Carlina Duan’s new poetry collection, Alien Miss, delves into the history and experiences of Chinese people, particularly how immigrants and their families face or have faced marginalization in the United States and also how they find success. Poems go back to the Chinese Exclusion Act barring entry to the U.S. for Chinese laborers and are later contrasted by cozy family meals while growing up in America.

The contrast stands out, as one line reads, “I pledge allegiance. to history, who eats me.”

These disparities between experiences pepper the poems. Family with its relationships and histories figures strongly into the experience, as in the poem “Love Potion”:

in July backyards, my aunties filled picnic tables

with barbeque ribs, Chinese sausages in neat, pink

rows. they cast love potions for me whileslicing seedless watermelons to wet, red songs.

in their mouths fit prayers or the improbablestuff of roses, dreams. but say what

you want. my aunties. they made a worldfor me in their kitchens.

they taught me how to live.

The loving scene directly counters "the time I stood at the intersection / carrying my black suit of hair and the woman stopped in / her shiny car, rolled down her window to scream something / vulgar….” On the one hand, history and identity bring life and connection. Yet at the same time, history, and the notion of otherness, wrongly and harmfully exclude people.

The poems also explore being a woman, daughter, mother, and grandmother. The stories of “wái po as she was back / then,” a daughter traveling with her father, and female cycles add another dimension of identity to the poems. The poem “Aretha Franklin Sings ‘Amazing Grace’ in a Sequined White Top” narrates how,

Aretha sings and beads of sweat

trace her jaw and fall relentlessly into the earth. amazing

grace, how sweet the sound of women who’ve worked

to scrub their names back into themselves.

The women in these poems are resilient.

Duan is a writer-educator from Michigan. She earned her MFA from Vanderbilt University, and she is currently a doctoral student in the University of Michigan’s Joint Program in English and Education.

I interviewed her about Alien Miss.

Q: What brought you to Ann Arbor and the University of Michigan?

A: Actually, I returned to Ann Arbor after some time away. Ann Arbor is my hometown: I grew up here, and then attended U-M as an undergraduate. After graduating, I spent time learning and growing with beloved communities in Bandar Pusat Jengka, Malaysia, and in Nashville, Tennessee. One way of looking at “return” is that I arrived (back) to the University of Michigan to pursue my Ph.D. in the Joint Program in English and Education, so that I could study the ways we teach (and enact) creative writing. But the deeper truth is that I also returned to learn how to love a familiar place anew. I’ve been surprised by the abundance of strange and sweet and wild textures that have come with returning to a place that carries so many of my former selves. I wrote about this experience in Ecotone Magazine not too long ago.

Q: How did you know you wanted to become a poet?

A: As a kid, I kept journals pretty meticulously; I loved illustrating and I loved writing and I really loved reading. But I was inspired to pursue poetry by Jeff Kass, my creative writing teacher at Pioneer High School. Journaling and writing poems were activities I cherished, but I did them in private as a kid, without a real audience or understanding that you could make a life (rather than a hobby) out of poetry. Kass really encouraged me to take it one level further and to honor my own poetry by putting time, effort, and more importantly, love into my craft. He brought in visiting poets to our class, such as Aracelis Girmay and Angel Nafis. He read our class his poem drafts. He published some amazing books (Knuckleheads, Dzanc Books) while I was in high school, and seeing Jeff and writers like him read their poetry out loud changed my life. I was 14 years old when I signed up for my first poetry slam, at Jeff’s encouragement and insistence. I was shy in high school, and poetry invited me to be brave and to trust listening to myself. I started attending poetry workshops at the Ann Arbor Neutral Zone, and by my senior year of high school, I earned a spot on the Ann Arbor Slam Poetry Team, where I got to meet incredible youth poets, many of whom are still friends today, and who are also writing and publishing beautiful books (check out the poets Jasmine An and Sara Ryan). Jeff Kass was the first person outside of my family members to ever call me a writer. I owe him—and teachers like him—an unending spool of gratitude; rather than being a gate-keeper, he was and still is a door-opener, and his mentorship and belief in youth poets changed my life.

Q: You mentioned that you are in the University of Michigan’s Joint Program in English and Education as a doctoral student, where you study community-engaged writing and documentary poetics. Tell us about your program and what you are working towards in it.

A: Sure! I’m in a joint Ph.D. program between the School of Education and the English Department, which essentially means that I—and the incredible graduate students in my program—are all invested in interdisciplinary questions around teaching, language, literacy, and literature. Despite having been in school for now over two decades (eep/eek!), I love that I’m growing myself as a scholar and a writer constantly, and I feel excited to be able to do it surrounded in such good company—fellow students and faculty in the English & Education (E&E) program have been tremendously inspiring in my three years here. Right now, I’m in the early stages of conceiving my dissertation; I’m interested in exploring the ethics of using historical imagination in documentary poetry—which is a genre of poetry that Alien Miss falls under. To offer a very loose and incomplete definition: documentary poetry describes poetry that reappropriates, adapts, or references archival source material in its poems; as a result, this genre of poetry is quite obsessed with history. My own research looks at how documentary poetry might offer a reparative way to access and rewrite communal history, and asks: How are poets thinking about and managing decisions around power, communal accountability, and identity as they write and imagine alongside historical research?

Q: Alien Miss is your second book, and it contains a reflection on family stories and family across the generations. Your acknowledgments say that the collection is “one big love poem to my family.” Could you share more about what that means to you?

A: I see the poems in the book as reaching across time zones, oceans, and generations to touch my familial line with tenderness, love, and respect. I grew up in the Chinese diaspora in the Midwest, so distance, language, and time separated me (and other second-generation kids like me!) from fully knowing my extended relatives and elders in a way that I mourn. However, I see the poems as a way to disrupt that diasporic loneliness; these poems are ways for me to spend time with, slow dance with, and converse with my family—both immediate and ancestral—to shower them in respect, to show up for them across the page with laughter, to pay homage to their dailyness and their living. I also see the poems as serenades to my parents and to my sister, who are the loves of my life.

Q: As you are highlighting, the description of your book reads, “Duan reflects on the experience of growing up as a diasporic, bilingual daughter of immigrants in the American Midwest….” How do you see yourself in these poems?

A: In the first section of the book, titled “Alien Miss,” the speaker is part autobiographical, and part invented: She is a compilation of my own experiences and the experiences of my matriarchal lineage, and women I read in the archives. I created a multi-vocal speaker for the first section of my book because I wanted a way to connect multiple historical moments in time: in the first section, the speaker moves across time and place. For the remaining two sections of the book, the speaker is very much me—a daughter of the American Midwest, and the eldest daughter of immigrants. As such, I see myself refracted back in the poems through a long river of questions and questioning: Each poem was an attempt to answer, for myself, the question of how to hold and write my own history. The speakers in my poems acknowledge that, while they arrive from spaces of violence and sorrow, they (and I) descend from a lineage that, yes, is also unflinching in its joy.

Q: One word that came to mind as I read was contradiction for the ways that history and society have treated Chinese Americans with inequities, in contrast to the family stories in the poems, and I found that same word in one of the blurbs on the back of the book. Do you also see the scenes and stories as bringing contradictions, or do you see them another way? Why?

A: Contradiction is certainly one of many words I would land on; part of my goal with Alien Miss is to map out the messy, daily ways that the ongoing lives and loves of my own Chinese American experiences carry on, despite the erasure and diminishment bound within a long history of Asian American exclusion and violence. Unfortunately, we’ve seen iterations of Asian American violence continue onward, especially in the past few years amidst the pandemic, and my book also grapples with the question of ongoingness of such trauma and violence in a U.S. diasporic context; what does it mean to continue to survive? The history, in all its violence, needs to be told, but I also wanted to make poems that spoke to the very real tenderness, acts of communal and familial care, and joy-making I’ve often witnessed and participated in. Elizabeth Alexander writes, Many things are true at once, and I wanted my book to speak to that simultaneity and nuance.

Q: As I read, I began to wonder and also look for what you might be hoping readers learn about identity and belonging from these poems. There are so many things, and these poems feel so necessary. What do you want for these poems out in the world?

A: I continue to struggle with how we teach and narrativize history. So often, there is the myth of neutrality or of passivity when it comes to reading history books, and I think poetry can be a possible space to disrupt that. How is the project of writing history forever evolving, never neutral, always a question of power and proximity? One thing I hope to make clear is that Chinese American history is certainly not a monolith, and my book expresses my own particular experiences attempting to make sense of my relationship to this history, and also my desire to find the language to encompass what felt unspeakable for me. My poems walk alongside the wise and wondrous words and labor of poets and writers like Jasmine An, Jane Wong, and Chen Chen, all of whom I feel humbled to be creating alongside. I hope readers not only read my book, but take the time to research and read other writers who are asking and nuancing these questions around historical storytelling and cultural memory as well.

Q: The Midwest setting of many of the poems feels familiar, and it provides both a home and a hostile environment at different times. The poem “On Mackinac Island, I Cast a Spell” says, “o, lips I part as I walk past a new body / of water and love what I love and stir it all into / a cauldron: eggplant, plastic fork, black & wet / eye wedded to the water.” How do you use your experience of the Midwest in your poems?

A: I’m passionate about employing images of the Midwest that are not just images of cornfields and suburbia in my poetry. Something that gets on my nerves is when people talk about the Midwest as if we’re a region of nothingness, and as if poetry is only being made in New York and the Bay area, the coastal cities. Some of the most innovative poets I know are from the Midwest; we create and are creatives! In writing actively about the Midwest, I’m trying to interrupt some of that discourse around the Midwest as homely, boring, backward, or empty. I’m also from a great lake state, so I feel incredibly allegiant to my bodies of water and am humbled by—and always learning from—the landscape around me. If history is not neutral, then neither is the land we’re on. (In Michigan alone: I’m thinking about the Flint Water Crisis; I’m thinking about the University of Michigan’s coercive purchase of its land from the Anishinaabeg and Wyandot nations; the list goes on). My use of Midwest imagery is to conjure up the Midwest as a complicated (rather than simple) place: a place of deep beauty, and also a place of contradiction (to borrow from your earlier question), a place I feel accountable toward. I believe we need to be responsible to our land and its history in order to better tend to its future, and for me, writing about the Midwest is one potential route toward that act of responsibility.

Q: What is on your nightstand to read?

A: Right now, I’m reading Ted Chiang’s Exhalation, Kat Chow’s Seeing Ghosts, and Craig Santos Perez’s Habitat Threshold.

I recently finished Safia Elhillo’s Home Is Not a Country, which is a Y.A. novel-in-verse—which stunned me and opened my eyes to what could be possible with the poetic form. I’ll also make a plug for Jennifer Huang’s Return Flight, which is such a riveting book of poems, by a wonderful poet who lived in Michigan not too long ago!

Q: You also note in your acknowledgments that the stories in Alien Miss are not final. Will you continue them elsewhere? What is next for you?

A: What I mean is that as a writer, my ideas are constantly evolving and re-evolving, so whatever gets published in print in the book has an afterlife in my mind: the writer I am today would re-tell the stories in Alien Miss a bit differently than my former-self did. That’s the beauty of writing, I think. As we grow, we are always returning to and further complicating our earlier stories. I included that note in my acknowledgments to say, the stories are not set in stone, even if they seem that way through their physical published format. Oftentimes, I think we are eager to turn to the paper book as the final, “finished” authority, but I wanted my book to be an invitation to myself and to many other readers and writers to pick up where I leave off and to further trouble and grow the poems in Alien Miss.

As for what’s next: I do feel obsessed with writing about history, though I haven’t really been writing poetry lately; I’ve been working on a manuscript of creative nonfiction essayettes instead, that largely focus on translation, transcription, “creative” capital, the historic role of the scribe, and handwriting. I’m also fascinated by the genre of ecopoetics, and I think my next poetic project is going to be more in conversation with environmental space and land.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.