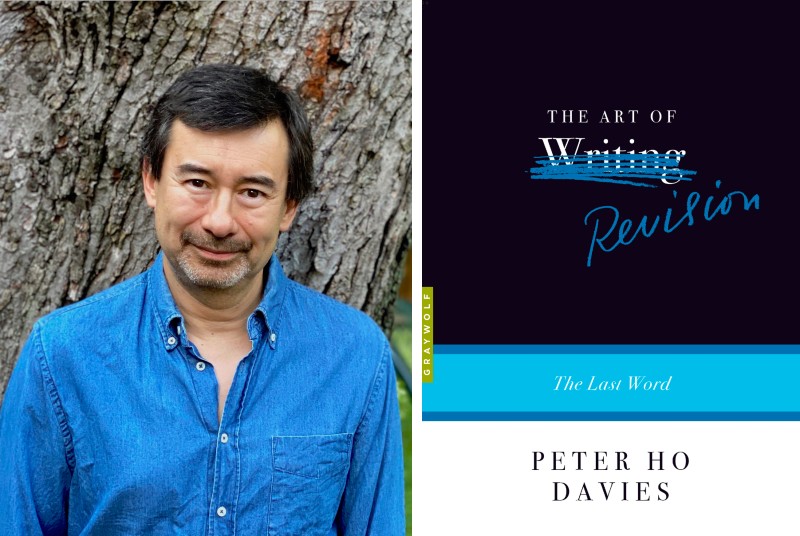

When the Draft Is Done: Author and U-M professor Peter Ho Davies on "The Art of Revision"

How do authors go about the revision process?

In novelist and U-M professor Peter Ho Davies‘ new nonfiction book, The Art of Revision: The Last Word, he observes, "As a teacher of writing, I’ve often been struck by the sense that revision is an overlooked, underaddressed, even invisible aspect of our work: the ‘elephant in the workshop,’ if you will."

Davies goes on to discuss approaches to revision, the need for it, and a number of examples.

Theories of writing, such as “write what you know,” do not lend themselves to revision well, Davies says, because writing instead serves as an act of discovery. The medium of typewriter or word processor changes the process from painstaking typing to countless drafts as new versions are saved over the previous one on a hard drive, useful in some ways and less deliberate in others. An author’s questions become, “What’s changed?” and “How do I know when a story is done?”

Davies proposes that "a draft might be seen as an experiment designed to test a hypothesis.” This perspective on writing reveals to the writer what they are thinking and then also guides revision. That hypothesis may or may not prove right as the writer proceeds. Davies says, "You make a choice, pursue it, discover it was wrong, and … go back to the previous draft. Is this wasted time, wasted endeavor? I’d rather call it a successful experiment."

An attempt that turns out to not be right is as informative as the path that is right. Ultimately, “Revision … is the sum of what changes and what stays the same,” he says. The author revises to discover which should be which.

Davies is the Charles Baxter Collegiate Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Michigan and the author of five other books. I interviewed him about The Art of Revision.

Q: What prompted you to write a book about revision? It started with a talk you gave, right?

A: That’s correct. The book began as a craft lecture at the Napa Valley Writer’s Conference in the summer of 2017, if memory serves. I don’t actually write a lot of lectures, but I like the nudge that conferences like Napa and Bread Loaf give me. Both also have great, smart audiences of students and fellow faculty—which slightly intimidates me, but also obliges me to up my game.

Q: Did your view of revision evolve as you wrote this book?

A: Evolve, yes, or perhaps to use terms I deploy in the book about revision itself, my views of the subject deepened and expanded. Revisionary movement isn’t always about change per se, but sometimes about seeing more, or further into what you already have.

Q: I am curious about your own revision of this book about revision. What revision did you do for The Art of Revision? How did you know when it was done?

A: A lot of expansion, of course, to get from a 45-minute lecture to a short book. I was able to illustrate my arguments with more detailed examples, and also to delve into some subtle side issues such as the way technology (the movement from the typewriter to the computer, say) has influenced how we revise. Still, even now, as I’m enjoying teaching a class on revision to my graduate students, I’m itching to further revise my book on revision!

Q: While reading The Art of Revision, it struck me that this is not a book only for writers but also for readers. Did you imagine a crossover audience while writing this book?

A: I hoped so. There’s a personal narrative to the book, a memoir element that I wanted to be an engaging, moving read. I suspect too—as perhaps suggested by the rise of auto-fiction—that there’s a lot of overlap now between readers and writers. All writers are readers, of course, but a lot of readers are also writers. Finally, my fundamental sense of revision is that it’s an act of seeing and re-seeing our own work, which is to say, it’s an act of reading ourselves (albeit a skill we hone by reading others).

Q: The memory with your father that you fictionalized in several ways is threaded throughout the book as an example of revision. The scale of revision grows large with the idea that you present of “revising his life” in your own choices. Other examples in the book show writers revising the same stories throughout their lives. What is a piece of advice that you may have about keeping up with this long game?

A: It’s my favorite piece of writing advice, borrowed from Flaubert who said that “Talent is long patience.” Revision exists in time, we need time to see the potentials in our work and to fully enact them, which is to say that patience is a gift for any writer (though all of us are often in a hurry to finish). It’s taken me 40 years to understand that story about my father which seems an age, of course, but the journey was absolutely worth it.

Q: You suggest that passages that are cut may be puzzle pieces that fit into a different draft. Do you find yourself going back to this document of trimmed but saved passages as fodder for the next piece of writing?

A: To be sure. I’m a slow writer—though maybe we’re all slower than we’d wish (there’s that note of impatience again!)—which means I hate to give up on something or throw it away, so I often find myself returning to old bits and pieces. I keep a file of them, a long document really that I scroll through in fallow periods (several of those snippets have checkmarks beside them now to indicate I’ve found a home for them), but some of them also just stick in my memory and come to mind when I need them.

Q: What other books on revision and writing do you recommend?

A: I list several at the back of my book, but my go-to is always anything by Charles Baxter on writing. His essays in Burning Down the House and The Art of Subtext are the gold standard and I can’t wait for his new one, Wonderlands, out in July.

Q: When I asked you what you are working on next during our previous interview for Pulp, you told me about The Art of Revision. With this book published, have you turned your attention to a new project?

A: Yes, tentatively. There’s often a lull between books for me – 2021 when I had a novel, and the craft book out in the same year was very much the exception – so the new one is only slowly coming into focus. It’s just in my head at the moment, but I’m starting to see it, so I’m hoping to get to the desk this summer once the semester ends.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.