The One-Woman Show “All Things Equal: The Life & Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg” Tries to Humanize the Late Supreme Justice

At a 2021 family funeral, one of my aunts, whom I hadn’t seen in decades, immediately guessed which car in the lot was mine: “I saw something with Ruth Bader Ginsburg on it hanging from the rearview, and I said, ‘Dollars to doughnuts, that’s Jennifer’s car.’” (Guilty!)

So, when I arrived at the Michigan Theater on March 14 to see the touring one-woman show All Things Equal: The Life & Trials of Ruth Bader Ginsburg by Rupert Holmes, the deck was already stacked.

But let’s be honest: I was hardly the only fan at the show’s packed Ann Arbor performance. As a feminist icon who arguably did more than anyone to advance women’s legal rights in the 20th century, RBG long ago achieved progressive, secular sainthood.

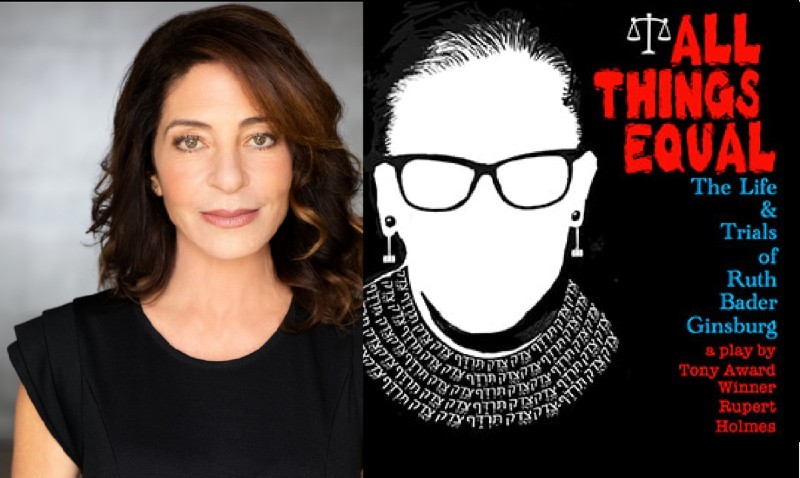

This ultimately poses a challenge for Holmes and his show, which stars Michelle Azar and is directed by Laley Lippard. How do you bring such a lofty figure down to earth and make her human?

Because frankly, despite Holmes structuring the play as an intimate talk between RBG and a couple of her granddaughter’s young friends in the justice’s chambers, it’s hard to not feel as if we’re prostrating ourselves at the altar of this powerhouse legal mind’s legacy.

To start with, the show’s frame is somewhat problematic (as it almost always is). The construct of a person providing a verbal highlight reel of her life over 90-plus minutes, with a small pause here or there, never truly feels natural or real. Plus, seeing the show in a large 1,700-seat venue works against the intimacy the show seems to crave.

More than likely, though, Holmes and his production team aim to educate young people, as well as those who know little of RBG’s life and legacy, so bringing the show to huge audiences across the country makes commercial (if not artistic) sense. As a teaching tool, the show probably works quite well.

But speaking as someone who knew a lot about RBG before setting foot in the theater, I’ll confess that All Things Equal didn’t bring me closer to her as a heroic-but-fallible human, despite Azar’s impressive, endearing performance and the production’s technical polish.

Tom Hansen’s depiction of Ginsburg’s warm-but-professional workspace, which includes a lectern, a classic desk and chair, some bookshelves, and a tasteful area rug, feels like an external expression of her spirit. It’s even lit by designer Mike Billings to help us make shifts in time and place.

Billings also provides projections and video that allow us to see (and sometimes hear) the people and moments Ginsburg references as the show unfolds. Devon Renee Spencer, meanwhile, captures RBG’s feminine-but-no-nonsense style through various small costume adjustments onstage, including a long, draping scarf Azar uses to pull back her loosened hair when RBG revisits her early days as a law student and young mother.

And sound designer Shaughn Bryant plays a few bars of the operas Ginsburg (and her late friend and fellow Justice Antonin Scalia) loved, as well as aural glimpses of precisely what is said to and about Ginsburg as she fights over time to secure women’s rights.

She famously and brilliantly achieved this goal by fighting for men who found themselves struggling against gender constrictions that somehow disadvantaged them. In the end, this pushed the Supreme Court, and thus our country, a bit closer to the ideal of gender equality.

No small feat.

Even so, Holmes does, near the show’s end, take pains to touch briefly on three instances when RBG’s less-than-careful public comments undermined her values, like when she unwittingly criticized Colin Kaepernick for kneeling during the anthem without knowing why he had chosen to do so. This seems a pointed effort to demonstrate that even the Notorious RBG was human and made a mistake now and then.

But it’s a drive-by moment of fallibility in what otherwise has the feel of hagiography.

Jenn McKee is a former staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News, where she primarily covered theater and film events, and also wrote general features and occasional articles on books and music.