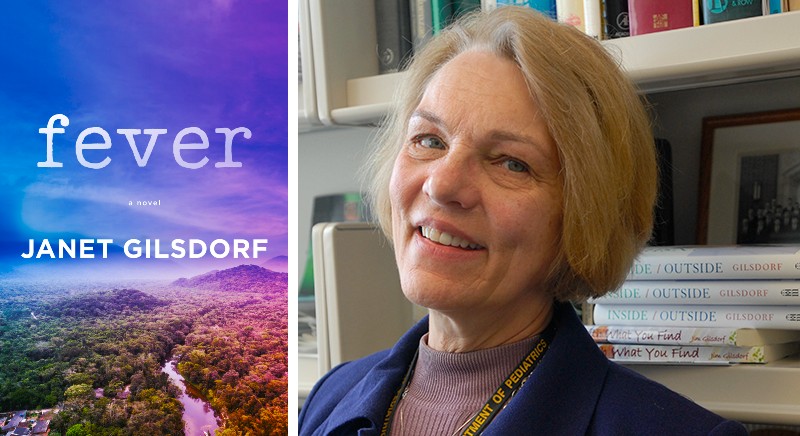

Dr. Janet Gilsdorf's novel "Fever" charts a mysterious illness and a researcher's race to discover the bacteria causing it

On a getaway with a colleague to visit family in Brazil, Dr. Sidonie Royal instead finds herself in a race to save children falling ill with a mysterious disease—and she experiences grief when they do not make it. Janet Gilsdorf's novel Fever tracks Sid’s subsequent research attempts back in Michigan to find out what is causing the deaths.

As a professor emerita of epidemiology and pediatrics at the University of Michigan, Gilsdorf is the right person to write a novel on this topic. Her work involves studying pathogenic factors, molecular genetics, and the epidemiology of Haemophilus influenzae, a bacterium that causes invasive and respiratory infections in children and adults. It is this bacterium that Sid, the character in her novel, is trying to understand.

Many hurdles appear along the way for Sid. One problem consists of her belligerent lab mate, Eliot, who always seems ready with criticism. At one point, he informs Sid:

“Look, there’s no problem with your results.” Eliot whapped the graph with the back of his hand. “The only problem here is your expectation of the right results. If you’re going to ignore the outcome, you shouldn’t bother doing the experiment.”

While Eliot is cantankerous, the question becomes whether they can nevertheless learn from each other.

Sid’s own passion for microbiology both inspires and challenges her:

It all started when she first stared into a microscope in her 4th grade science class, saw a swarm of E. coli through the lens, and realized that they were alive. “They eat and breathe, like we do,” her teacher had explained. “Like my cat Lilac does,” Sid had told the class. Sid loved to let her mind wander down the path of interesting microbial questions: how bacteria cause infections, how the immune system controls them, how to harness that control for the benefit of patients.

This excitement for research keeps Sid going even when the answers are not easily found.

Alongside the urgent puzzle of the children’s deaths, the characters’ personal lives go through happy moments and also setbacks. Another lab mate, Raven, learns a secret about her brother in Brazil. Sid herself grapples with her own relationship that is strained by long distance:

And she missed Paul, or at least some parts of him. She missed the way he laughed—it emerged slowly with a smile and a quiet chuckle and grew into a riotous guffaw. She missed the dinners he used to cook and the nights they watched movies. But missing didn’t dictate destiny.

Whether their connection will survive her ambitions for her research fellowship in another state becomes another ongoing question for Sid.

I caught up with Gilsdorf to interview her about her career in Ann Arbor, novel, and writing life.

Q: How did you come to live and work in Ann Arbor after studying and practicing medicine around the United States early in your career?

A: We moved around a lot to many interesting places populated with interesting people early on while my husband and I completed our medical training and fulfilled his military commitment. Following all that, I was offered an outstanding position at the University of Michigan and have been here ever since. The University has been very good to me, and I’ve been good to it.

Q: As an accomplished doctor, scientist, and professor, tell us what also draws you to writing as a creative outlet.

A: I have learned so much from my young patients and their families and was compelled to find a way to express that. I found telling stories, theirs and mine, to be a satisfying way to do that. Also, I love the biological sciences and enjoy finding metaphors in the principles and systems of biology.

Q: When and how did you start writing creatively?

A: I was very late to begin creative writing and like many other things in my life, it began through serendipity. Over the years, I have always enjoyed the process of writing and authored many scientific papers and grant applications to support my research lab. So when my kids were in high school, a friend mentioned that she had joined a writing group and invited me to come along. I agreed. When it was my turn to present something to the group, I wrote a short, really awful piece. One of the other writers kindly noted that I had a point-of-view problem with one of the characters. I didn’t know what that was and decided that if I was going to do creative writing, I needed to learn the basics. For the next 12 years or so I spent my summer vacations attending writing workshops. I’ve been in the same writing group ever since.

Q: Fever is not your first novel. What was unique about writing this particular book?

A: The outbreak of the fatal infection among young children in outback Brazil featured in Fever is based on a real outbreak that occurred in 1984-86 in two small towns in the Brazilian state of São Paulo. My research focused on the bacteria that caused the outbreak, Haemophilus influenza, so the cluster of cases piqued my interest. The high fatality rate was extremely unusual considering the form of the bacteria that caused those infections. Something had happened to that strain. It had gained, likely through gene transfer of some sort, the ability to cause extremely serious, often fatal, infections only in young children. Many microbiologists worked very hard to understand this new feature of the bacteria but, to this day, the full scientific explanation for its enhanced pathogenicity remains a mystery. At first, I figured that, as a novelist, I could invent whatever scientific explanation for the bacterial mutation I want. But, the science behind it all is very dense, too dense to be the driving force behind the plot for a lay audience, so I abandoned that goal and decided to focus on other aspects of the outbreak.

Q: On a larger scale than in your novel, the world recently experienced a pandemic, too. Did you write Fever during the COVID-19 pandemic? Did the recent pandemic change how you or your readers approached your novel?

A: I wrote Fever prior to the SARS Cov 2 pandemic, which didn’t change my approach to the book at all. I can’t speak to the reaction of readers. I can, however, speak to the reaction of editors: my agent had some difficulty selling the book to a publisher because the editors were wary of one microbial outbreak (in the book) on top of another (in real life). Some of the editors were young mothers and couldn’t handle reading about these infections in children. Fortunately, Megan Trank, the editorial director at Beaufort Books, loved the book and wasn’t bothered at all by the microbial outbreak and sick babies.

Q: The character, Sid, gains inspiration from her mentors, such as when she was an undergraduate and "listened while the speaker, Dr. Bausch, told of the ways bacteria make trouble for people. She detailed how they move from place to place and evolve to survive wherever they land. How their toxins drill into human cells and disarm vital metabolic pathways.” Tell us what inspired you to go into this field of microbiology, too. Was it for the same reasons as Sid or other reasons? Why?

A: I am not Sid, and she is not me, although we have shared a few similar experiences as physician-scientists. Thus, my reason for going into infectious diseases/microbiology was different from hers. For me, books have always been a huge influence. I was introduced to the field of medicine by Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis; The Feminine Mystique by Betty Friedan taught me that I didn’t have to follow in my mother’s footsteps and could, indeed, go to medical school. Then, upon rereading Arrowsmith as a pediatric resident in Houston, Texas, I became fascinated with the power of microbes. Interestingly, the main character, Dr. Martin Arrowsmith, was modeled after Dr. Paul De Kruif, a microbiologist at the University of Michigan who showed Lewis how research laboratories work.

Q: You study the same bacterium that Sid is trying to learn about in your novel. What is so compelling about this bacterium?

A: Many aspects of H. influenzae are fascinating: It only lives on the respiratory tissues of humans, so all of its life processes occur there. The type b form only causes serious infections in young children as older children and adults are immune to infection even though the bacteria may live in their noses and throats without causing any trouble. It was erroneously thought to be the cause of influenza, which is why it has its (wrong) name. It has unique capabilities for sticking to human cells, for gathering iron (needed for it to grow) from its environment, for picking up DNA (and, thus new genes) from other bacteria on the respiratory tissues. I could go on and on but will spare you!

Q: In one scene in Fever, Sid presents at a conference and, after her talk, you write, “It felt as if she were royalty, wrapped in ermine, perched on a throne with a crown on her head, and surrounded by armloads of roses.” I wonder if you related to Sid since you are both doctors and researchers. How did you use your experience to create the character and experiences of Dr. Sidonie Royal?

A: I am intimately familiar with scientists, how they think and how they live, their value systems, their loyalties, their priorities. Pertinent to the quote cited above, I’m very familiar with the stratospheric highs of scientific successes and with the hellish lows of agonizing failures. Similarly, I’m well-acquainted with the joys and frustrations of the practice of medicine, with the details of assessing patient signs and symptoms, with medical procedures, tests, and treatments. Thus, I’m able to apply that hard-won knowledge to my characters who are scientists and/or physicians. In fact, I really enjoy doing that.

Q: For readers interested in reading more books like Fever, what do you recommend?

A: Actually, I don’t read many medically oriented novels, because I have lived that life so much and many such books seem contrived and inauthentic because they are tone-deaf to the intricacies of medicine. One novel that got it right is The Dutch House by Ann Patchett, maybe because she is married to a physician. Recent books I’ve read with compelling characters, and nothing to do with medicine, include The Summer Book by Tove Jansson, A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki, Summerwater by Sarah Moss, This Other Eden by Paul Harding, and the Lucy Barton series by Elizabeth Strout.

Q: You have been writing throughout your career. What are you working on next?

A: Yes, I’m always writing. For a number of years, I’ve tried to write a novel in linked short stories and all previous attempts have turned into regular novels. I’m partway through another try at it, and I think I’ve got it, finally. It has to do with evolution and a red dress that is passed down through an extended family. I’m also revising (yet again) a novel set in Alaska, where we lived during the Vietnam War.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.