Universal Horror: Classic monster movies at the Michigan Theater

In the '30s and '40s, the most horrific words in Hollywood were "Dracula," "Frankenstein," "Mummy," and the names of the iconic creatures that implanted themselves into the popular culture.

For people who love cinema, an even more horrific word reigns supreme in Hollywood's marketing lexicon today: universe. This is the idea that several movies can be grouped together in order to manipulate ticket buyers into seeing films they might otherwise skip. We have the Marvel Universe (Avengers, Iron Man, Thor) at Disney and the DC Universe (Man of Steel, Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice, Wonder Woman) at Warner Brothers, and Universal attempted to launch their "Dark Universe" last summer with the Tom Cruise vehicle The Mummy. Yes, Universal plans to make a series of films connecting their classic monsters.

Thankfully, the Michigan Theater comes to the rescue every Monday in October by offering up the Classic Monsters series featuring the Universal originals: 1931's Dracula (Oct. 2, 7 pm) and Frankenstein (Oct. 9, 7 pm), 1935's Bride of Frankenstein (Oct. 9:45 pm), 1932's The Mummy (Oct. 16, 7 pm), and 1941's The Wolf Man (Oct. 23, 7 pm).

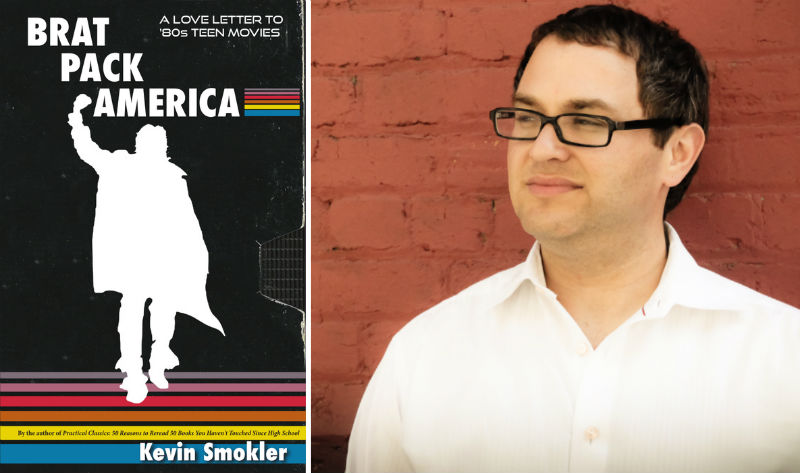

Back to the Future: Kevin Smokler, "Brat Pack America: A Love Letter to '80s Teen Movies"

The 2010 Academy Awards telecast devoted a nearly seven-minute chunk of airtime to commemorating the life and work of John Hughes, a director/writer/producer who never received an Oscar nod in his life.

Kevin Smokler's recent book, Brat Pack America: A Love Letter to '80s Teen Movies, explains why those Hughes films stand the test of time. But his interests run much wider than just Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club, and Ferris Bueller's Day Off. Throughout his enjoyable survey of the decade, Smokler persuasively argues that, during this time, setting began to matter more to teen films than ever before.

Smokler will return to his original hometown of Ann Arbor on Monday, June 12, at 7 pm for an appearance at Literati. I spoke with the author about Reagan-era high-points as varied as Risky Business, The Lost Boys, and Back to the Future, as well as the Hughes canon.

Q: How did the concept of Brat Pack America come to you?

A: I had been wanting to do a book about '80s teen movies for a long time because I always saw them as a group, and not just because of John Hughes or because of the label Brat Pack that was unceremoniously given to this group of young actors. I had been an early teenager at that time and had recognized that there was a bumper crop of movies made about people my age and slightly older than me. I'm not the first person to come to that realization. The movies have been written about in one way or another several times, and several times admirably. I didn't quite see what I had to add to that story. So since that's usually where I begin most of my books -- having an idea off in the distance like the green light at the end of the dock -- I just sort of wander toward it and hope when I get there the path I've taken is clear, and I have something to report back once I get there.

In this particular case, I spent a lot of time with a stack of DVDs, and what I noticed is I kept circling back to this memory I had of my father, who had grown up in Detroit and really liked telling me and my brothers about all of the things that came from the middle of the country. One of those things was John Hughes; he was enormously proud of the fact that John Hughes was a Michigander and made all of his movies proudly about the Midwest. I remembered thinking to myself, you say "Chicago filmmaker" and you could say William Friedkin or John McNaughton, or a hundred other people, but in my mind, the first name that comes forth is John Hughes. So I started thinking about that and thinking about the movies at that time that were self-consciously about the places where they happened. One night, late into the night and three iced coffees to the wind, I scrawled "Brat Pack America" down on a pad and fell asleep. That's where the idea started from. I've always been an Americana buff, so I'm always trying to work the word "America" into the things I do and actually, in this case, it made sense.

Q: Your examination of the early hip-hop movies being specifically about New York was eye-opening.

A: I'm sort of dubious of culture writing that assumes a part is actually a whole so I think there are books that say, "I'm going to write about the indie-rock movement of the 1980s," and they say so up front, and they set their boundaries by that, and that's what they stick to. Then there are books that say the same thing but say, "I'm going to write about the music of the 1980s," but they only write about white guys with guitars. That's just sloppy at best, and at worst it's making a lot of assumptions. I was very careful not to assume an '80s teen movie meant John Hughes and his closest disciples because I think the category is much richer than that. When I went looking, there were these two strands that popped out at me, the doppelgangers of the John Hughes movies -- the dystopian dark comedies like Repo Man and Heathers, and also the early generation of hip-hop movies, because hip-hop was a young artform perpetuated by young people.

Q: One of my earliest moviegoing memories was walking down to the local one-screen theater in my hometown and being denied a ticket to see The Breakfast Club because it was rated R. It was the only Hughes film to have an R rating, and I was curious if you have any thoughts about that.

A: In my research about Hughes, and in talking to his family, it didn't come up all that often, that ratings were an issue. Hughes largely made movies with one or two studios. For someone who was a savvy businessman, he didn't have a whole lot of patience for or interest in the business of making movies. I think he dealt with studios as little as possible, and the agreement he had with them, even if it was unspoken, was largely that he would bring in something on time and on budget that they can use and make money on without spending a ton on marketing. He delivered on that promise over and over again.

I think when he wanted to do something that was more challenging, like The Breakfast Club, he, in fact, wanted to make The Breakfast Club first, but the studio sort of said, "How exciting is seeing a bunch of teenagers sit around all day going to be?" So he very smartly chose to make Sixteen Candles first, which is a lot more high concept and whose appeal is more straightforward. Not that Sixteen Candles was such a box office success, it wasn't, but it was proof of concept that Hughes was a self-sustaining unit who could do things his way and good actors wanted to work with him.

I think they [the studios] sort of counted on him to deliver the goods affordably. I don't think they worried too much about ratings. Maybe they just assumed that if the R rating was prohibitive for teenagers seeing The Breakfast Club in the theater it would bounce back on video, and it turned out it was a box office hit anyway.

Q: Have you rewatched these movies with kids?

A: I don't have kids, but I've watched them other people's kids, which has been pretty interesting. I watched both and Back to the Future with a friend's young teenagers, and the two things that jumped out at them are that the kind of bullying you see in The Karate Kid isn't done much anymore, at least not in their San Francisco public school world. It's more of the spreading vicious rumors on social media kind of bullying. The thing I have to say about Back to the Future is, the chronology was very confusing for them because to them 1985 is the past, and 1955 is the way past, so most of the time travel jokes were lost on them, and the social mores surrounding parents and kids were lost on them, too. I think they mostly thought it was funny, and the DeLorean was cool.

Q: I have two teenage girls, and I know the ones that speak to them as closely as they did to me at that age are The Breakfast Club and Ferris Bueller, both of those really work for them still.

A: I didn't notice this until I read some biographies, but John Hughes always operated from sort of an archetypal, slightly mythic, instead of grounded in realism, approach. He clearly makes use of lots of Hollywood archetypes. What is Sixteen Candles if not a Doris Day/Rock Hudson movie? What is Ferris Bueller if not On the Town but with high school students instead of sailors? I think the fact that those movies hold up is in part due to plots and tropes that have been with us since the beginning of moviemaking. Another part of it is due to John Hughes skill at being specific and archetypal and relatable and mythical at the same time.

Q: When you mentioned the time frame in Back to the Future it made me think of one of my favorite passages in your book about how Francis Ford Coppola's adaptation of S.E. Hinton's The Outsiders is a film shot in the '80s, set in the '60s, with the iconography of the '50s, from a master of the '70s.

A: And filmed like it was set in the '30s, like it was in CinemaScope like Gone With the Wind. I think a lot of that had to do with how young S.E. Hinton was when she wrote it. She was writing a book about her peers, it was published when she was 20, so she was doing on-the-ground reporting. It was not nostalgic when it was written. This may be me being elitist, I think because the book was set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and not in some major urban area, I think the iconography is not the leading edge. There is a reference in some of S.E. Hinton's later work to hippie kids, but even though The Outsiders was published the same year as the Summer of Love and Sgt. Pepper, it feels like it comes from an earlier era. It was coincidence that the movie was made in the '80s, 15 years after it was published. That's when it came to Coppola's attention. He had kids just the right age to read the book in school. It did dovetail nicely with the fascination with cars with tailfins, and leather jackets and greasers that was part of the early '80s culture.

Q: After revisiting all of these movies doing research for the book, I'm curious what movie were you surprised by how your feelings toward it changed, either positively or negatively, since you saw them as a teenager.

A: The chapter on horror movies didn't make the final manuscript of this book. As a kid, I was too scared to go see horror movies, so I was shocked at how great a movie Halloween is. I just thought it would be trashy and cynical and gross, and I think Halloween is a masterstroke of modest budget filmmaking, of making something out of nothing. I think Halloween is genius. I remember being crazy about The Lost Boys, and I think The Lost Boys is now your basic teen vampire movies. It's only 90 minutes, so by the time it gets ridiculous, it's over. But I think it looks great; that's mostly Joel Schumacher's doing, and it makes spectacular use of Santa Cruz. There's been a dozen movies shot since in Sana Cruz and they all work to varying degrees, but when you go to the Yelp reviews of the Santa Cruz boardwalk nobody mentions Killer Klowns From Outer Space or Riding Giants or any of those movies; they all mention The Lost Boys. I don't think The Lost Boys is a great movie; it's a greatly produced movie. I think it looks great, and the use of setting is fantastic.

I think it really would have helped had I seen Gremlins at that age. I didn't. In retrospect, there's not much to it. It's fun, it's well cast, it's naively racist, which is annoying. Many Steven Spielberg acolytes at the time were playing with this vaguely racist idea of a poor helpless group of white kids menaced by a mean outside non-white force. Gremlins is an example of that; Adventures in Babysitting is an example of that. I don't think those movies were intentionally prejudiced, but they were playing with a lot of notions that seemed at best dated and at worst terribly closed-minded. I don't think those movies wear very well. And I'm not the kind of person who opposes showing kids movies with outdated ideas; it's a good excuse to have an honest conversation with them. But I think if your kid is watching Sixteen Candles and guffawing at Jake Ryan's date rape joke, that's a teachable moment.

Q: What's the best movie that you couldn't work into the book that you really wanted to?

A: Risky Business. I had a whole chapter that was fun to write, I hated to let it go, about Risky Business, Adventures in Babysitting, Midnight Madness, the whole kids-let-loose-on-the-big-city-at-night kind of movie. It was too similar to other chapters and the manuscript was too long and it had to go. Risky Business is one of my absolute favorite movies. I think that movie is fun to watch, it's a masterstroke of satire of '80s youth and ambition. It's sexy as hell. It's one of the most inspired scores in movie history.

Q: One of the most intriguing concepts of your book is that place matters. You really get at how these movies defined where they took place, and that was a necessary element to the overall story. I'm curious, post-Brat Pack America, what films do you see are worthy of a spot on that map?

A: I don't think they use place in exactly the same way. If we're just talking about teen movies, a movie like (2015's) Dope is a really interesting reconfiguring of the map of Los Angeles where working class black and Latino kids live. If Dope was made a decade before, it would take place in South Central. Dope, made in 2015, takes place in Inglewood. Very self-consciously Inglewood. That's not just the interest of the director -- who set his film The Wood (1999) there as well -- but also showing that sort of archetypal working-class black and Latino teenage story has moved there geographically. I think that's really interesting.

I think a movie like (2012's) The Perks of Being a Wallflower and (2015's) Me and Earl and the Dying Girl, which are both set in Pittsburgh, is infinitely more interesting having been set in Pittsburgh and is an exemplar of how Pittsburgh is the revitalized former rust belt city. Is it crucial those films take place in Pittsburgh? No. Does it say something interesting about what place Pittsburgh holds in our national consciousness? Yes. What other movies self-consciously takes place in Pittsburgh? The Deer Hunter. That's a totally different Pittsburgh than the one in Perks of Being a Wallflower. It says a lot about how far we've come that the last shot of Perks of Being a Wallflower is -- the music swells [David Bowie's "Heroes"] -- and they emerge from the Fort Pitt Tunnel and there they are driving into downtown Pittsburgh. If that movie was made in 1987, it would have them going the other way through the tunnel and driving away from downtown Pittsburgh.

In the '80s we were coming out of an era where moviemaking seemed like a very coastal thing and that was largely the interest of Coppola's generation of filmmakers. My argument in Brat Pack America is the opening of the image of growing up in America at this time. It becomes a life cycle event that happens all over America, not just in the Mid-Atlantic, the Northeast, and California. There's a democratizing effect on the stories of being young in America at that time. That becomes less necessary once A) It's done, and B) Once we have the Internet and we can travel further, faster in our minds without ever leaving home.

Perry Seibert is a movie lover, freelance writer, and founding member of the Detroit Film Critics Society. Follow him on Twitter @Perrylovesfilm.

Kevin Smokler will talk "Brat Pack America: A Love Letter to '80s Teen Movies" at Literati on Monday, June 12 at 7 pm. Read our previous interview with Smokler as part of a preview for the Michigan Theater's "Kids in America: '80s Teen Classics" series.

Terence Davies' film "A Quiet Passion" covers the life of poet Emily Dickinson

At first listen, Terence Davies' voice seemingly betrays his 71 years. Even with his charming British accent, the Englishman sounds gravelly, like he can't get as much air into his lungs as he might like. But then it takes about 30 seconds of hearing his words to understand age might not explain this condition as well as a literally breathless enthusiasm for whatever topic he's discussing.

I spoke with Davies about his latest film, A Quiet Passion, a biopic about Emily Dickinson that details her complicated family relationships, her unconventional religious beliefs, and her own self-esteem issues in order to celebrate a unique life and illuminate her poetry. The film opens at the Michigan Theater on Friday, April 21.

AAFF 2017 | Totally Out There/Classic AAFF: "The Pink Egg" & more

The Pink Egg

Features in Competition | Totally Out There | Classic AAFF

If you're going to make a film that fits the aesthetic of the Ann Arbor Film Festival, Luis Bunuel makes for a near-perfect starting point. Director Jim Trainor begins The Pink Egg with a quote from the celebrated surrealist: "You can find all of Shakespeare and De Sade in the lives of insects." That sentence offers a pithy declaration of artistic intent, and Trainor follows through, offering viewers a one-of-a-kind evocation of the animal world.

Employing boldly minimalistic and colorful sets that could double for an unhinged, low-budget children's program, Trainor casts humans clad in long-sleeved, hooded unitards to act out the mating rituals, lifecycles, and surprisingly human experiences of various wasps, bees, and insects. Alternately humorous, tragic, and inspiring, The Pink Egg remains a defiantly uncommercial picture due to the lack of dialogue, and the seemingly bizarre actions of the nameless characters. You may find yourself asking why some of the female characters paint pink and blue tubes with lotion, meant to represent seminal fluid, and why those tubes suddenly change color.