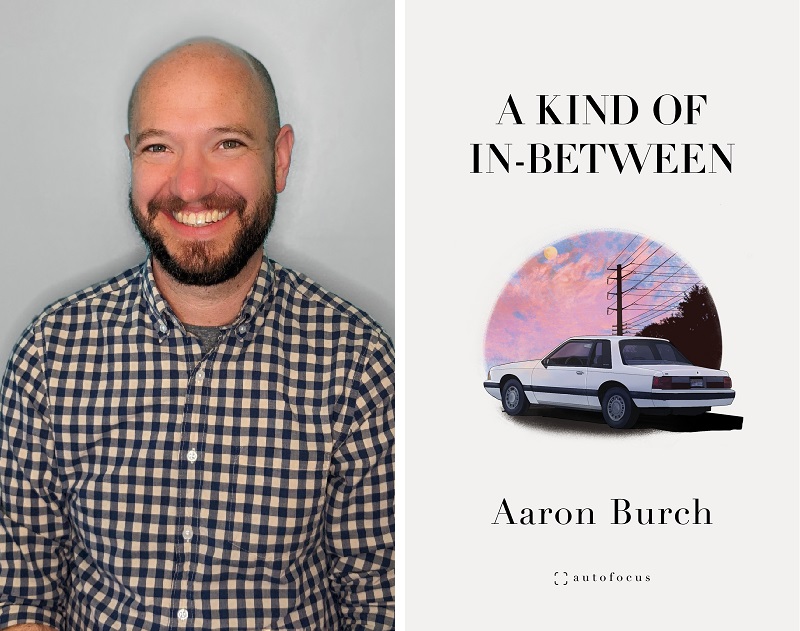

AARON BURCH EMBRACES AMBIGUITY AND NOSTALGIA IN HIS NEW ESSAY COLLECTION, “A KIND OF IN-BETWEEN”

Aaron Burch recounts major life changes and memories in the essays of A Kind of In-Between. Throughout the pages, Burch questions what is important in life. What do you remember? What does it mean? Why are you happy or not?

Focusing on the places he has been is one approach that Burch takes to inform these inquiries. He shares that he grew up in Washington and has subsequently lived in Michigan and Illinois as an adult. In the sentence that lends itself to the book’s title, he narrates his road trip:

I’m somewhere in the middle of Pennsylvania, driving around this big, long turn while also going down a decent decline. I don’t know how steep; I don’t really have any idea how to measure or guesstimate that kind of thing. I can tell it’s steeper than anything in Michigan but less so than Washington, a version of the kind of in-between that I return to again and again—known but not, neither childhood nor adult, not quite then or now, here or there.

This ambiguity begins in the physical world and then seeps into other contexts. The human urge to name and define things breaks down when something is neither one nor the other. Burch concludes this essay called “Ohiopyle” with a question: “Were you to ask me, somewhere in the middle of Pennsylvania, whether home meant Washington or Michigan, what would I answer? I’m not sure.” Still, maybe one does not have to decide, as Burch highlights “the interconnectedness of everything and everyone” in the first essay of the collection.

The Lord of the Screens: U-M professor Daniel Herbert chronicles the history of New Line Cinema in "Maverick Movies"

Late August at Hotel Ozone. Stunts. Get Out Your Handkerchiefs. A Nightmare on Elm Street. Critters. House Party. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me. Dumb and Dumber. Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery. Hedwig and the Angry Inch. The Lord of the Rings. The Notebook.

These films all have one thing in common: New Line Cinema.

University of Michigan film and media professor Daniel Herbert chronicles and analyzes the history of the production studio and its films in his new book, Maverick Movies: New Line Cinema and the Transformation of American Film.

Herbert initially launched his interest in New Line by teaching a course on the company. Back in 2010, the idea came from U-M librarian Philip Hallman, who also speculated about a possible book. The class evolved, and Herbert conducted extensive research that culminated in his book. He studied the Robert Shaye-New Line Cinema Papers and the Ira Deutchman Papers, which are in the Screen Arts Mavericks and Makers collection at the Special Collections Research Center of the University of Michigan Library. The closing lines of the book describe the origins of its title:

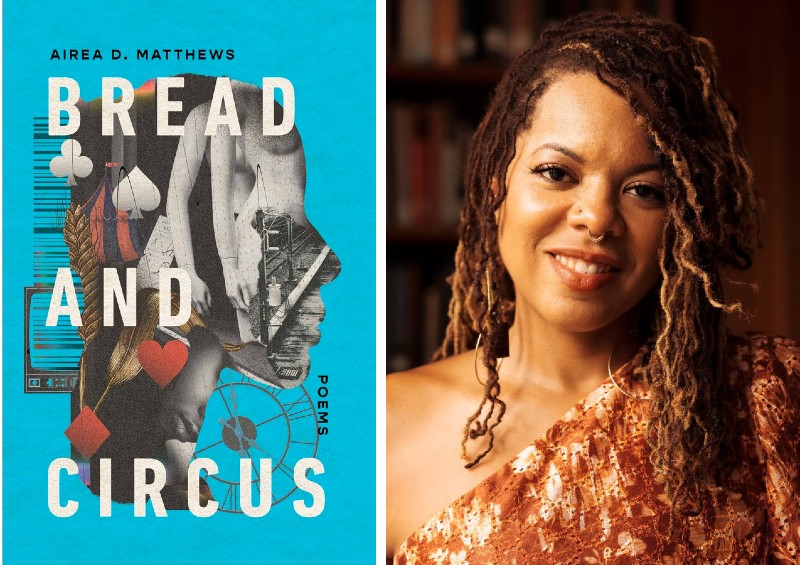

Public and Personal Policies: Airea D. Matthews’ autobiographical poetry collection questions economic theory amid the realities of poverty and violence

Necessity and amusement. Sustenance and transaction. Security and turmoil.

Airea D. Matthews’ autobiographical poetry collection, Bread and Circus, brims with contrasts. One situation or item is paired with another to show a lack or miscalculation. The poems hover on a precipice, even as the guests “…watch a lovely commodity / reluctantly agree to her own barter.”

Early in the book, the poems witness a shotgun marriage, and the family grows in the subsequent years. Making ends meet results in how “Papa despised the vestiges of a hand- / out” – and especially “one specific symbol of his failure – corn.” Over time, the father’s drug addiction causes trauma, along with broken promises like, “I owe you a bike, right?” though it never materializes. These memories stick in the poet’s mind, as the poet reflects on a past hurt:

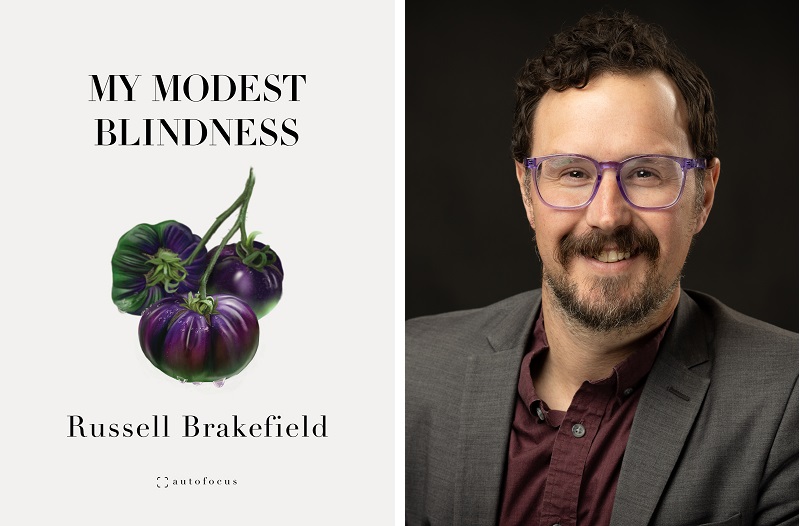

Russell Brakefield's New Poetry Collection, “My Modest Blindness,” Reflects on His Experiences With Keratoconus

Russell Brakefield’s new poetry collection, My Modest Blindness, is both “a telescope of loss” observing how a health condition called keratoconus robs the sense of sight and an exploration of this new state where there are “maybe a million small truths held just out of reach.” Brakefield’s poems take a “reluctant trowel” to excavate this experience and then “step into a life of shadow.” The poet sees familiar life receding and seeks “to reclaim another.”

The book contains six sections, starting with “Paper Boats” which launches the poet unwillingly down this path with keratoconus. The next two sections bear titles suggesting a clinical examination in “Pathology” and a historical approach to eye conditions in “A Brief History of Corrective Technology.” The fourth section called “Ancestors” looks backward and forward, including family, art, and references to film and other mediums. “In Between Worlds” is the penultimate section, in which the poet identifies lessons, such as humility, and in the “Coda,” begins “again to play.”

The poems themselves, however, remain untitled, which has the effect of immediate immersion into the poet’s dimming world. The exception to titles, though not exactly formatted like a traditional title, is in the intermittent series of one-stanza poems that consistently start with the word “Entry” and a number in the first line. “Entry #7” describes heirloom tomatoes like those pictured on the front cover:

A tag in the dirt tells

me the varietal is Indigo Apple, though all

year I’ve been calling them Bruises or Savory

Plums or Skyline Just Before Nightfall.

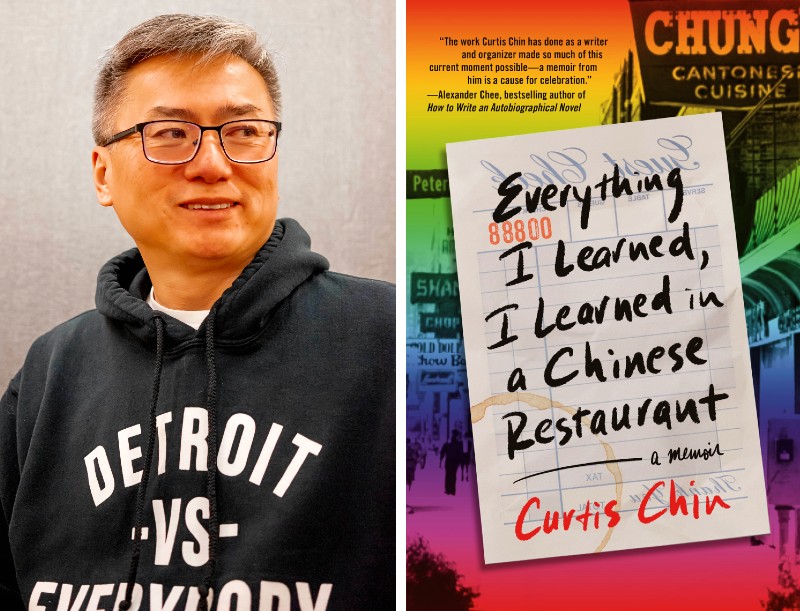

Egg Rolls and Racism: Curtis Chin's memoir recalls growing up in his family's Chinese restaurant in the Cass Corridor

Some lessons arrive early in life and stick with you for years.

For author Curtis Chin, the lesson is “Work hard. Be quiet. Obey your elders.” These instructions become a mantra for Chin as he grows up in his family’s restaurant, Chung’s Cantonese Cuisine, in Detroit. The advice gets him through unfamiliar situations.

Chin recalls his experiences in his new memoir, Everything I Learned, I Learned in a Chinese Restaurant. With humor and the kind of introspection that comes with looking back on one’s life, Chin narrates stories from his time in the restaurant and Detroit, as well as his journey to becoming a writer at the University of Michigan. In fact, he worked at Drake's Sandwich Shop as a student. Food, family ties, and Chin’s identity as a gay American-born Chinese serve as throughlines in the book.

The politics and racism of the '80s parallel Chin’s formative years. Chung’s was in the Cass Corridor, a rough area at that time, and its clientele spanned all races and even drew Mayor Coleman Young as a diner. Chin’s father recognized the lessons to be had from talking with customers and brought his sons from the back kitchen into the dining room: “[H]e had really brought us there to discover the outside world, which was sitting right at our tables. All we had to do was listen.”

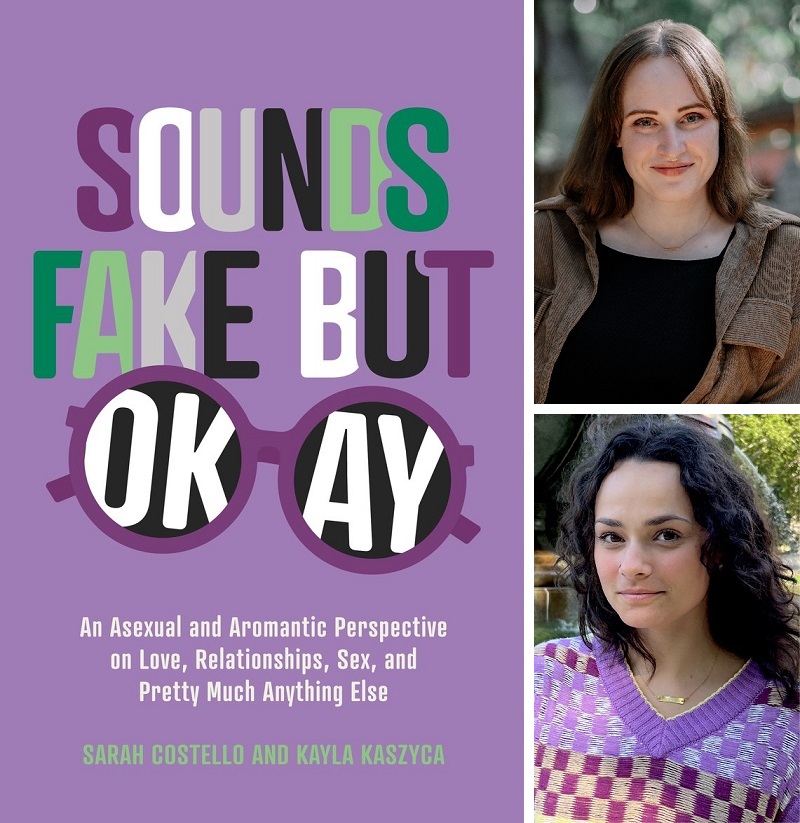

Purple-Colored Glasses: Sarah Costello and Kayla Kaszyca Provide Asexual and Aromantic Perspectives in “Sounds Fake But Okay”

University of Michigan alums Sarah Costello and Kayla Kaszyca host the podcast “Sounds Fake But Okay” and recently came out with their new nonfiction book, Sounds Fake But Okay: An Asexual and Aromantic Perspective on Love, Relationships, Sex, and Pretty Much Anything Else. The book delves into what it means to be asexual and aromatic. Along the way, they define many terms, both in the glossary at the start of the book and in subsequent chapters. They offer their own personal examples and quotations about identities from other people who responded to a survey.

Like many things, asexuality and aromanticism are on a spectrum, referred to in the book as aspectrum or aspec. Costello and Kaszyca describe their understanding of this range of perspectives and identities as having “purple-colored glasses”:

Once a person first puts on those purple-colored glasses and sees the potential a new mindset unleashes, it’s understandable that they may not want to take them off. It’s understandable that one may choose to embrace the unknown and the uncategorizable in contexts beyond relationships with one another and apply what the aspec lens teaches us to their relationship with themselves.

The authors emphasize the many variations along the aspectrum, given that “the aspectrum is a seemingly infinite trove of words and concepts and love whose combined meaning cannot possibly be fully mastered by a single mortal being.” Aspectrum is not one-size-fits-all but rather a plethora of individualities to which a person may relate.

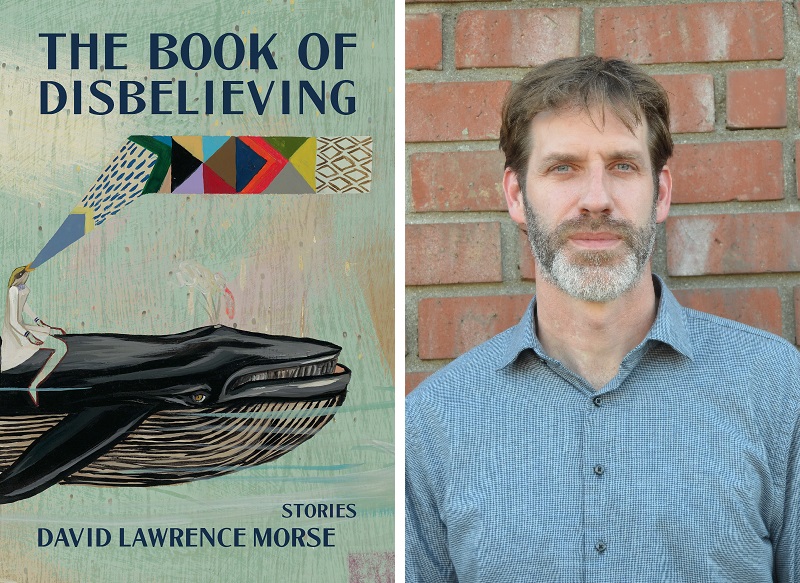

David Lawrence Morse's Short Story Collection, "The Book of Disbelieving," Challenges Distinctions Between Fantasy and Reality

Sea creatures, time, mating, life, and death all take a twist under David Lawrence Morse’s pen in his new short story collection, The Book of Disbelieving.

The worlds of Morse’s short stories are not our worlds, though they are not too different. In The Book of Disbelieving, he changes an element or two of life, which becomes the premise of the story. As one character reflects, “The mind can imagine anything, but that doesn’t make it so.” The stories also read like fables with a moral, even though there are no animals who speak.

The first story, “The Great Fish,” contains a civilization that lives on the back of a large fish and only allows pairs of people to stay together if they successfully procreate. When Osa and the narrator, who are partners, disagree about their future, Osa focuses on her own plans. Her significant other reflects on their circumstances: “ ‘What’s wrong with floating,’ I asked. ‘That’s the way the world works.’ ” Osa does not want to float through existence anymore, though. They do not agree because her mate wants to keep “the precarious life it was my responsibility to preserve.” As they forge their own paths, the surprising thing is what they miss.

These stories gravitate to the topic of death. One story covers a person with the role of “oarsman” to row away the deceased. Another story called “The Serial Endpointing of Daniel Wheal” follows a desperate character trapped in a society that has a special unit to remove those who have “endpointed.” Passing on carries a great deal of mystery and abruptness, as Daniel reflects on his life:

That was memory. That was past. And Charlotte was past and the past is past. As much as he wanted to relish the experience, he couldn’t hold on to the moment, the moments slipped free too quickly, before he could appreciate them the moments ghosted into memory. Time is an endpoint that renders pleasure into grasping after nostalgia.

No one, including Daniel, is immune. Morse’s stories embrace “how it could all change in an instant. How you told yourself one thing but believed something else. But the thing you actually believed wasn’t the thing you wanted to believe.”

Morse earned a Master of Fine Arts (MFA) at the University of Michigan and now directs the writing program at the Jackson School of Global Affairs at Yale University. I interviewed him about his new book.

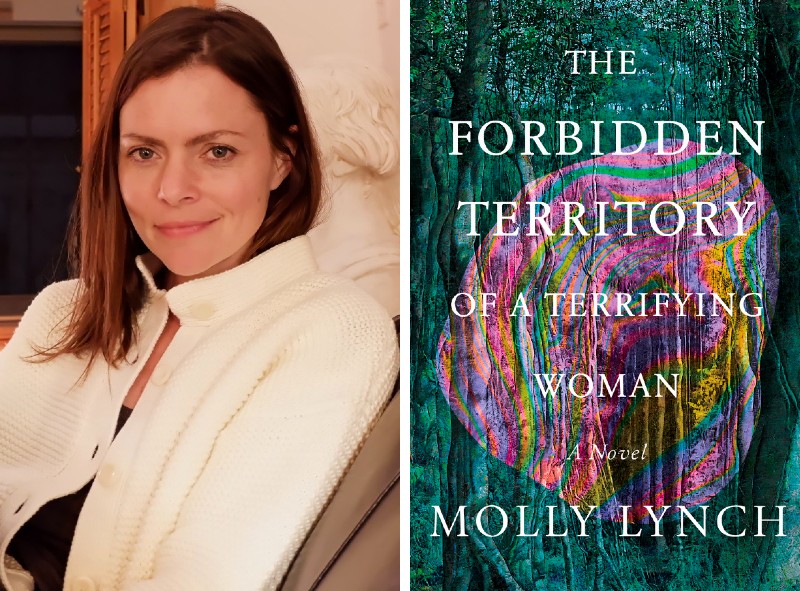

Late in the World: Molly Lynch's new novel tracks the willing disappearance of a mother and wife

Imagine that you have an urge to disappear and be unreachable.

Then, imagine that someone whom you care about has that urge, but you don’t know where they went or why.

Now, add many more layers of complexity to the woman who disappears given that she has a family, including a child, and a career.

These circumstances would raise many questions, and the premise of Molly Lynch’s new novel does just that.

The Forbidden Territory of a Terrifying Woman tracks Ada, a mother and wife who goes missing suddenly. Her husband, Danny, and son, Gilles, are left behind, bereft and confused. Yet, Ada is following her thoughts and feelings. With an omniscient third-person narrator, the reader gets insights into all the characters.

Early on in the book, the bond that Ada, Danny, and Gilles have with each other becomes clear, as “All three of them were one connected thing.” Yet, there are challenges:

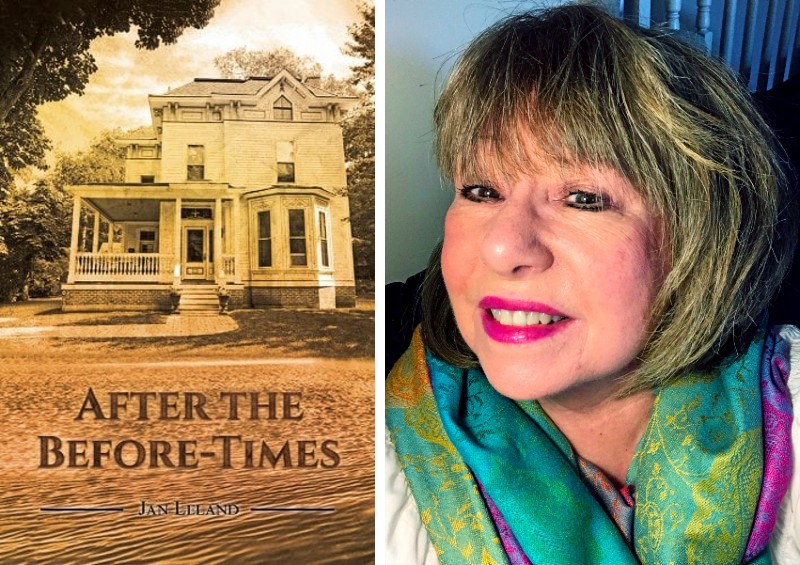

The debut novel by Ann Arbor author and therapist Jan Leland follows characters processing emotions in the early days of the pandemic

We all collectively endured the pandemic, but we each had an individual experience of it.

The unique but relatable stories from 2020 to 2021 are what Jan Leland tells in her new novel, After the Before-Times.

The circumstances in which Leland’s characters’ find themselves all differ, but they converge at the same time—when COVID-19 emerges—and in the same place: the Clearview Inn on Orchard Lake in Keego Harbor, Michigan. Through these characters, Leland portrays the stress and anguish—as well as the triumphs and coping mechanisms—of the early days of the pandemic.

One of these characters, Ashley Cooper who is known as Ash, works at The Book Shelf in town. The coronavirus affects her early on when her boss and close friend, Marla Phillips, sickens and passes away. As Leland is attentive to character development, we learn about Ash in detail:

Pretty and petite with shiny shoulder length curly brown hair and brown eyes, high cheekbones and dimples, Ashley was smart and curious. Although Marla felt Ashley needed life experience, she perceived an inner strength to Ashley. It did not take much for Marla to convince Ashley to take the position of Store Manager at The Book Shelf.

The job offered, in Ashley’s eyes at least, the opportunity to work and live in a small town where people were friendly and easy-going and where Ashley felt important and sophisticated in providing literary knowledge and expertise.

This opportunity for Ash allows her to not only engage with books but also meet many others with whom she becomes close.

The Dating Game: Julia Argy’s Debut Novel “The One” Chronicles the Fallacy of Finding True Love on a Reality TV Show

“‘I’m actually in the market for a new opportunity,’ I answered, and thus my journey to find love began.”

So starts The One, a novel by Julia Argy, a University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers’ Program alum. The main character, Emily, embarks on a whim as a contender on a reality television show, which is designed to whittle a group of women down to the individual who the male love interest, Dylan, selects to marry. Emily describes the show and the book’s premise:

At the base level, this is all a psychological experiment with a desired economic outcome: trap thirty people together as they fight for a limited quantity of the same thing, something everyone wants, true love, and the result will be scintillating enough to attract millions of viewers to sell advertising. And that, the real hypothesis, has proven true, season after season.

Emily must learn how the program works as it goes along because she has not watched past seasons, so she takes a critical approach rather than suspending her disbelief. As Emily further reflects, “Maybe the first set of contestants are meant to showcase the vast scope of women who desire Dylan, like going to a big-box store where at the head of each aisle is a sample stand, enticing you down to the rest of the similar wares. I need to figure out what brand of woman I’m supposed to be.” The “brand” she turns out to be is not what she expects.