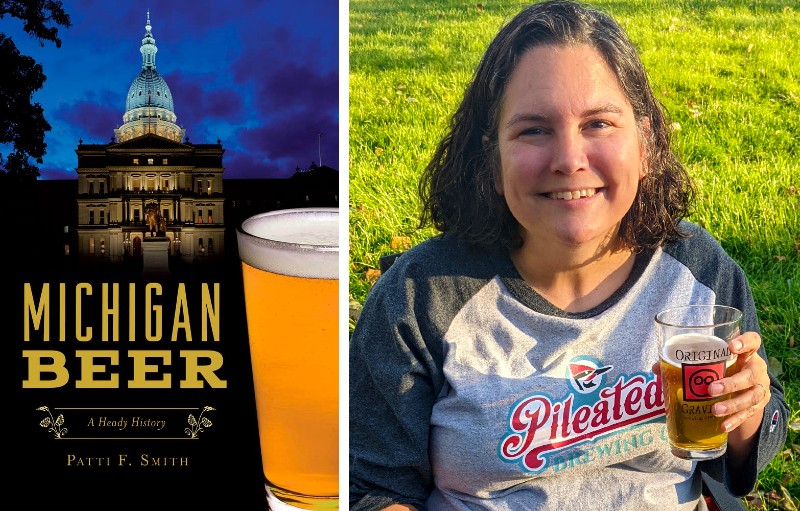

Patti F. Smith taps into the stories of brewpubs, brewers, and their beers in her new book, "Michigan Beer: A Heady History"

Patti F. Smith's introduction in her new book, Michigan Beer: A Heady History, may activate your thirst to take a seat at one of the state's many current establishments:

Like the waves that crash in the magnificent Great Lakes that surround Michigan, beer and brewing has constantly moved and evolved in the state. […] Come along on a trip through the history of Michigan’s brewers and beer as we explore, region by region, the history of brewing in our great state.

But Michigan Beer reports on mainly pre-World War II businesses and their beverages. Smith highlights the “first wave of brewers” who came to the U.S. from countries like Germany and Prussia. She also describes the “second wave” who endured or sprung up after Prohibition and also struggled during WWII. The “new wave” gets a dedicated chapter at the end of the book regarding breweries in the 1980s and onward.

Michigan Beer is organized by regions of the state: the Upper Peninsula, Western Michigan, Mid-Michigan, Eastern Michigan, and Southeast Lower Michigan, plus the “new wave” not divvied up by location. Each chapter spotlights numerous corners of the state from Copper County and Escanaba to Grand Rapids and Detroit, with many more cities showcased. Readers can look up their hometown, college town, or favorite vacation spot and see what breweries were once pouring there.

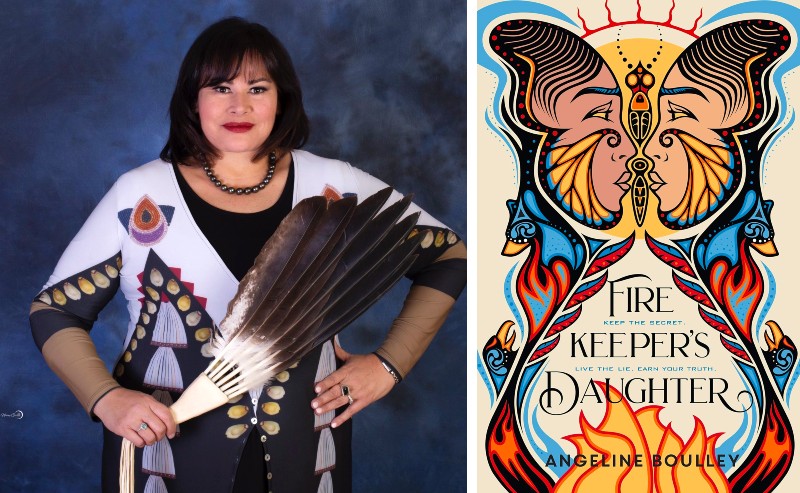

Angeline Boulley’s YA Novel, "Firekeeper’s Daughter," Follows a Native Teen Who Discovers Intrigue and Betrayal in Her Upper Peninsula Community

When author Angeline Boulley wrote her new young adult novel, Firekeeper’s Daughter, she had a goal for the thriller. She writes about her main character, Daunis Fontaine, in her Author’s Note:

Growing up, none of the books I’d read featured a Native protagonist. With Daunis, I wanted to give Native teens a hero who looks like them, whose greatest strength is her Ojibwe culture and community.

Daunis fills that role with resilience as a narrator, woman, community member, and confidential informant.

Ann Arbor District Library will host Boulley for an author event on Wednesday, April 6, at 7 p.m. at the Downtown Library.

In Boulley’s novel, Daunis experiences multiple tragedies in her Ojibwe community in a short amount of time. She then discovers that there is a related, ongoing federal investigation about a drug ring. Firekeeper’s Daughter tracks the steps that Daunis takes to unearth what is going on in her hometown of Sault Ste. Marie in the eastern Upper Peninsula of Michigan. At the same time, Daunis is entering her first year of college and grieving the deaths of loved ones.

As Daunis becomes embedded in the investigation, she must learn how to be a confidential informant and also reckon with the pressures and dangers of her role. FBI agent Ron Johnson tells her:

“If you as an agent of the law, obtain evidence illegally, then the information is inadmissible in court under the Fourth Amendment. It’s called fruit of the poisonous tree. It’s better for you to volunteer information and let us ask for clarification.”

Early on in the novel, she begins walking a tightrope of her role as a CI and relationships with her family and friends. The situation blurs as Daunis pretends to be dating one of the agents, Jamie Johnson, who has also joined the local hockey team to advance his undercover ruse.

Ojibwe teachings guide her actions, and Auntie, without knowing what Daunis is involved with, also advises her that:

“You need to be careful, Daunis, when you’re asking about the old ways.” She looks at me the way Seeney Nimkee does sometimes at the Elder Center. “There’s a saying about bad medicine: ‘Know and understand your brother but do not seek him.’”

Daunis continues exposing secrets and also learns about the further tragedy that, “Not everyone gets justice. Least of all Nish Kwewag.” As Boulley also highlights in her Author’s Note, Native women experience high rates of violence.

Prior to her talk at AADL, I interviewed Boulley about her novel and plans.

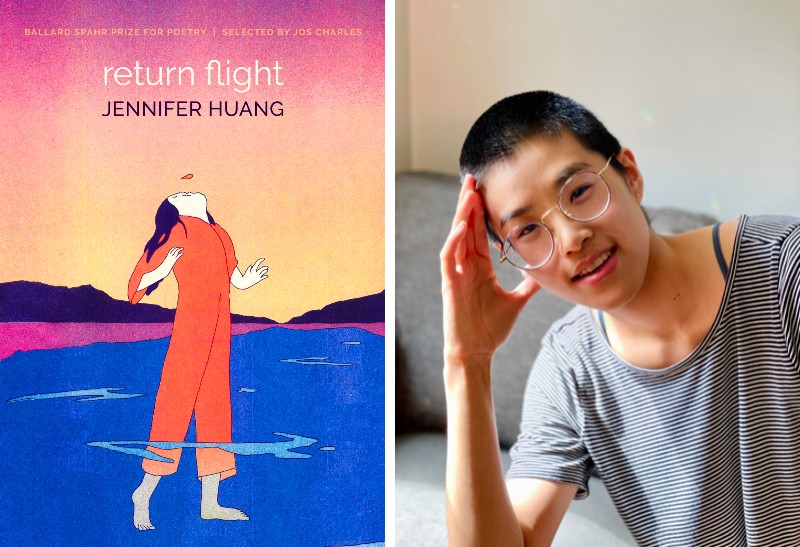

Jennifer Huang reconceptualizes home in their new poetry collection, "Return Flight"

Poems in Jennifer Huang’s Return Flight map the ways that a person can depart and return to themself, though sometimes that self is no longer the same. Huang holds an MFA in poetry from the University of Michigan Helen Zell Writers’ Program, and their collection won the Ballard Spahr Prize for Poetry in 2021 judged by Jos Charles.

Some of Huang’s lines suggest disillusionment, given that “This is not what I imagined.” Other lines show a separation from oneself and the effect of external influence when, “The distance between me and I grew / So you could love me as you’ve / always imagined.”

Return Flight plays with desire and how to get what is wanted and what is the cost.

Another poem, “Departure,” describes a meal at which “We would / choke down our food to get seconds though there was always plenty,” and when faced with delicacies, the father would "tell me, Chew slowly and feel what you are eating.” That advice to process slowly and notice could be extrapolated to a number of situations in these poems.

The search for self continues even as that evolves in Return Flight. The poem “How to Love a Rock” teaches us, “How you / worry now, let it go.” As the self is reclaimed, uncertainty remains when, “Unborrowed from rocks and salt and dirt and root, where I go from / here, I don’t know.” It could be anywhere, which fits with what Huang writes in the acknowledgments: “This collection is, in part, a search for home—and the realization that home is not a destination but a journey.”

Huang was a resident of Michigan and now spends their time in Michigan, Maryland, and other places. I interviewed them about Return Flight.

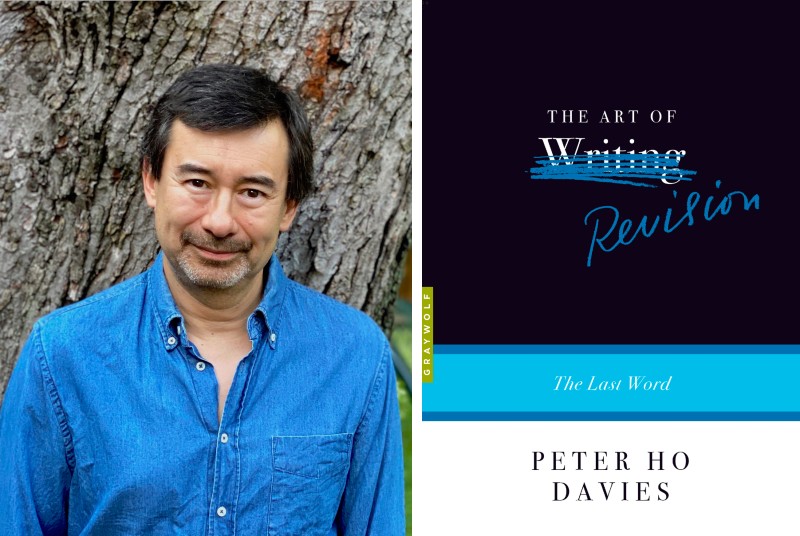

When the Draft Is Done: Author and U-M professor Peter Ho Davies on "The Art of Revision"

How do authors go about the revision process?

In novelist and U-M professor Peter Ho Davies‘ new nonfiction book, The Art of Revision: The Last Word, he observes, "As a teacher of writing, I’ve often been struck by the sense that revision is an overlooked, underaddressed, even invisible aspect of our work: the ‘elephant in the workshop,’ if you will."

Davies goes on to discuss approaches to revision, the need for it, and a number of examples.

Theories of writing, such as “write what you know,” do not lend themselves to revision well, Davies says, because writing instead serves as an act of discovery. The medium of typewriter or word processor changes the process from painstaking typing to countless drafts as new versions are saved over the previous one on a hard drive, useful in some ways and less deliberate in others. An author’s questions become, “What’s changed?” and “How do I know when a story is done?”

Davies proposes that "a draft might be seen as an experiment designed to test a hypothesis.” This perspective on writing reveals to the writer what they are thinking and then also guides revision. That hypothesis may or may not prove right as the writer proceeds. Davies says, "You make a choice, pursue it, discover it was wrong, and … go back to the previous draft. Is this wasted time, wasted endeavor? I’d rather call it a successful experiment."

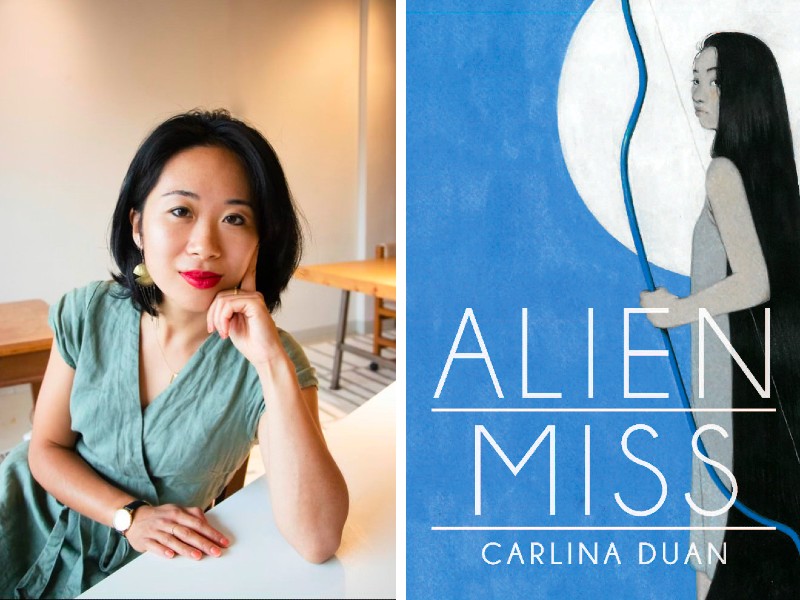

In "Alien Miss," Ann Arbor poet Carlina Duan explores the multiple identities Chinese Americans inhabit

Carlina Duan’s new poetry collection, Alien Miss, delves into the history and experiences of Chinese people, particularly how immigrants and their families face or have faced marginalization in the United States and also how they find success. Poems go back to the Chinese Exclusion Act barring entry to the U.S. for Chinese laborers and are later contrasted by cozy family meals while growing up in America.

The contrast stands out, as one line reads, “I pledge allegiance. to history, who eats me.”

These disparities between experiences pepper the poems. Family with its relationships and histories figures strongly into the experience, as in the poem “Love Potion”:

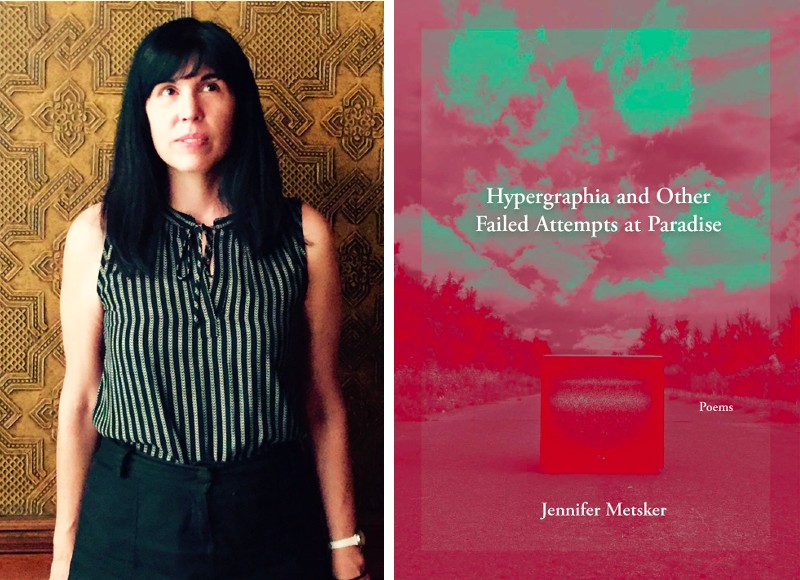

Welcome to "Paradise": Jennifer Metsker's new book of poems explores a bipolar mind

In Hypergraphia and Other Failed Attempts at Paradise, Jennifer Metsker’s poems articulate a bipolar person's thoughts as they unravel. The poems show the mind making associations outside of rules as obsessions, fears, and beliefs take hold.

One of the poems, “Beta Waves Are Not Part of the Ocean and We Prefer the Ocean,” brings us to a psychiatric ward. People living there take on feline qualities and have cleaning duties, noting, “There’s no escape / from being a tidy cat.”

Amidst the mind’s chaotic adventures, the outlook remains bleak because:

Grains, Beans, Seeds, and Legumes: Chef and U-M alum Abra Berens offers recipes and social context for them in her new book, "Grist"

When you start paying closer attention to a food or beverage, you notice more details among different types or brands. Experts who focus on wine or coffee, for example, are able to discuss the nuances and tasting notes of unique varieties.

But those aren’t the only foods and drinks that foodies and cooks can get to know on a deep level.

Abra Berens, a chef, author, former farmer, and U-M alum, brings this level of attention to beans, grains, legumes, and seeds in her new cookbook and guide, Grist. She writes about how her interest in grains took root:

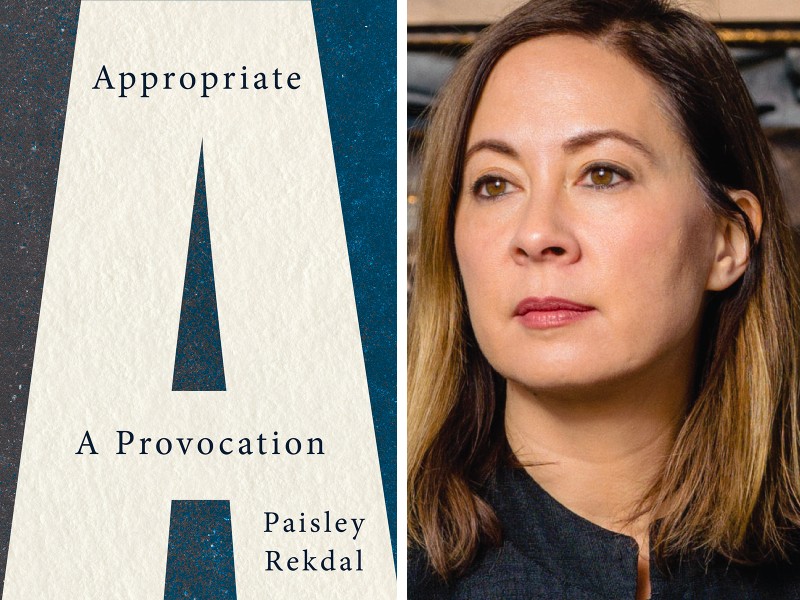

Utah poet laureate and U-M grad Paisley Rekdal considers the implications of cultural appropriation in literature in "Appropriate: A Provocation"

Paisley Rekdal examines cultural appropriation in literature in her new nonfiction book, Appropriate: A Provocation. However, this collection is not essays, as one might expect.

Instead, Appropriate consists of letters addressed to a student who is a new writer, and this structure offers a different, more conversational, and inquisitive tone. This recipient is not based on any specific person but inspired by many students and colleagues. The letters refer to the student as X.

Early on, the first letter defines the subject of cultural appropriation as being about identity. It is also, “an evolving conversation we must have around privilege and aesthetic fashion in literary practice.” Rekdal’s examples of the issue—both positive and negative, including hoaxes in which authors pretend to have another identity—demonstrate how important attention to the topic is.

Rekdal offers ways to understand, analyze, and navigate cultural appropriation. Rekdal asks many questions and also offers a list of them for evaluating one’s own work to let the reader consider what their answers are, too. She includes her own experiences from teaching, participating in conversations, and writing appropriative works herself.

You might be wondering whether cultural appropriation should just be off-limits, but Rekdal brings a more nuanced view, one that acknowledges some literature as effective and other literature as harmful. She writes to X, “When we write books that appropriate the experiences and identities of other people, X, we enter into the system in which we all participate but over which we individually have very little control.” This issue is so risky that Rekdal anticipates this question of “Do you opt-out?” The matter cannot be distilled so simply, though, because Rekdal offers instances when authors successfully write other identities than their own.

The question then becomes about what factors contribute to literature that engages in cultural appropriation working or not working. The answer changes, in part, based on the current moment in history and politics, notes Rekdal:

Race, Class & Miscegenation: Jean Alicia Elster fictionalizes family history in her new young adult novel, "How It Happens"

Jean Alicia Elster’s new young adult novel, How It Happens, chronicles the hardships and inequality faced by Black women from the late 1800s through 1950 and beyond. The story she tells has a personal note. It is the fictionalized account of three generations of Elster’s family, starting in Tennessee with maternal grandmother, Addie Jackson, and continuing in Detroit with her daughter, Dorothy May Ford, and granddaughter, Jean.

The book begins with a prologue that defines “miscegenation,” meaning the marriage, sexual relation, or other intimate affiliation of a person who is white and someone of another race. This topic has a lasting effect on this family when a prominent white man becomes the father of Addie’s daughters. The events that happen to the characters illustrate how race and class work against the women of this family in those eras.

May Ford describes how it happens to her daughter Jean:

Ann Arbor's Linda Cotton Jeffries keeps readers in suspense with her new mystery novel, "Seeing in the Quiet"

Two suspected murders 20 years apart, one of a child and another the death of an old woman. An observant photographer who was a child at the scene of the first murder and documented the second. A killer with a grudge. A kind-hearted detective who is a growing love interest.

These situations lay the foundation for Seeing in the Quiet, a new mystery novel by Ann Arbor author Linda Cotton Jeffries. At just under 200 pages, the plot-driven book moves quickly while the characters try to unravel what happened at each of the potential murders set in Pittsburgh.

Main character Audrey Markum lives with hearing loss, but her sense of sight has sharpened to the point that Detective Rod Rodriguez calls her “Scout” when she is called in to photograph crime scenes. She also is launching her wedding photography business. One case of a suspicious death brings Rod and Audrey closer and closer.

While all of this is happening, Gary Adams, the killer of his son who was the childhood friend of Audrey, is getting released from prison. He knows Audrey’s role in discovering his crime. Audrey finds herself facing multiple dizzying situations: the threat of a known killer, an unsolved murder, and the budding of a promising new romance.

Jeffries has published two other books with AADL's Fifth Avenue Press. I interviewed her about Seeing in the Quiet and writing life.