Caroline Kim's characters in "The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories" ask what is most important in life

A woman loses a child and yet she helps another, Suyon, pregnant with a baby rumored to not be by her husband, give birth. Then, with war breaking out in Korea, the woman meets an American, marries him, and moves to the United States. There, she finds herself engaging in animal husbandry and applies the same tactics she did with her acquaintance:

You get good at birthing horses and people send for you when they have difficult cases, mares too frightened and in pain to calm down, to do what is good for them.

You whisper the same nonsense you told Suyon: that they are beautiful and perfect and doing everything just right. Everyone, everything in the world loves them.

This woman’s dedication and strength to carry on through these significant changes in the short story “Arirang" attest to the resilient characters in The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories by Caroline Kim. It also shows how universal and necessary that encouragement and support can be, something we all need.

Kim’s stories in her new collection ask what is most important in life, with the options ranging from fortune or pride to family, truth, connection, and expressions of love. When a woman breaks down in “Magdalena,” a mother and daughter who attend the same church try to help, despite not wanting to be associated with her. They grapple with whether to address the woman’s dire situation or to judge the woman and try to distance themselves. As the mother tells her daughter about the woman:

U-M Zell visiting prof Sumita Chakraborty’s "Arrow" displays the poet's exploration of words' contradictory meanings

Going into reading Sumita Chakraborty’s debut poetry collection, Arrow, it’s not a secret that the book follows traumatic experiences. As she describes in “Sumita Chakraborty on writing Arrow,” which was shared with me by the publisher, Alice James Books:

Much of this book resides in a range of aftermaths: in the aftermath of the severe and prolonged domestic violence I experienced as a child and adolescent; in the aftermath of sexual violence; in the aftermath of my sister’s death; in the aftermath of breakups; in the griefs and anxieties that follow in the aftermaths of unending sociopolitical events; in the aftermath of unending ecological devastations.

Knowing this informs but does not explain the poems in Arrow, but it sets the stage for the intense emotions and scenes depicted in them.

EMU professor Christine Hume's "Saturation Project" offers a lyric memoir composed of three essays

Three essays fill Saturation Project, a new book by Christine Hume, a professor at Eastern Michigan University. Described as a lyric memoir, the text obliquely depicts various moments, ranging from Hume’s childhood to interactions with her daughter.

In the first essay, “Atalanta,” first-person accounts about personal thoughts, family, and a daughter intermingle with Greek mythology and examinations of feral kids raised by bears. Wanderings in the woods and through memories merge with ancient stories and animals in such a way that the distinctions between them blur, as Hume elaborates:

I read the story of Atalanta as if I were swallowing it, but it swallows me. Then I tell it to my daughter because I don’t have a childhood I can tell her about yet. I steal Atalanta’s, which is like mine in that the most longed for moments are inaudible.

It’s as if the essays are a way of remembering, but recollections are transposed, taking inspiration from other places.

Phil Christman traverses time, politics, and culture in his nonfiction essay collection "Midwest Futures"

This story was originally published on February 6, 2020.

What words come to mind when you think of the Midwest?

You may think about its geography, the middleness, or its position and moniker as the heartland with farming and small towns.

You might look at a map to see the 12 Midwestern states (from east to west): Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, Illinois, Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, and Kansas.

Perhaps you reflect on its seeming representativeness of American life. Or you study its history containing the displacement of indigenous peoples, manufacturing, and struggling economies.

Myriad ways, even contradictory ones, coincide to describe and understand the Midwest. Writer Phil Christman navigates them in his new book, Midwest Futures, a wide-ranging set of 36 brief essays organized in six sections. Part criticism and part descriptive essay, this nonfiction collection likewise exists as many things at once and navigates assorted perceptions, politics, history, literature, cultures, and pop culture of the Midwest.

Molly Spencer covers chronic illness, domestic life, and nature in her second poetry book, "Hinge"

Hinge by Molly Spencer shows a world in which the poet seeks to find footing in a constantly shifting landscape and body. Views, possessions, relationships, and physical capacity change and merge and vanish at various points. The multipart poem “Objects of Faith” reveals these different angles by looking at things like a window or a berry and distilling them to what they do: “To hold in place / once piece of the world” or “To be that ache / in someone’s mouth,” respectively. This instability and the feeling of being on the cusp of something appears through the changing seasons, motherhood, and domestic life.

This collection of poetry particularly examines chronic illness, its progression, and its effects. At times, the poet’s observations are stark:

In this family

of illness,

the doctor says,

the body

attacks itself.

The poet seems to consequently no longer trust the world to stay how it’s meant or desired to be. It’s as if everything has become more fragile and uncertain—the poem “Patient Years” tells us “safe is the shell of an egg.” The poet also asks the question “if the one you love / most will follow you down.”

Despite dark winter days, even darker dreams, and physical limitations in these poems, persistence is visible. The poem “Vernal” suggests hopefully that:

Food, immigration, and female experience intertwine in poet Jihyun Yun's book "Some Are Always Hungry"

Some Are Always Hungry by Jihyun Yun concentrates not only on cuisine but also on the ways the world views, consumes, and treats womanhood—how women are made to push through and past very physical, personal challenges, and to try again. The attention to these topics is inseparable from history, trauma, and family, whether it’s on memories of immigration, the shame carried in female bodies, or the comfort of a meal made from bodies of animals.

These poems tie together generational and physical pain, recipes, and urges—the urges to survive, to procreate, to eat, to seek fullness. They read in the way that you may listen to someone talking with the leaps between thoughts that are colored in by context and word choice. One poem looks back on a moment:

Alison Swan's poetry collection "A Fine Canopy" celebrates the natural world

The natural world and the built environment sometimes seem so enmeshed that the borders between them blur. We walk into the fluorescent lighting of a store and then back out into the day’s weather. We go to the beach and some sand trails, then back inside vehicles and homes.

Poet Alison Swan explores this complexity in the lives that we live both with nature and in our manmade world in her new collection, A Fine Canopy (Wayne State University Press). One poem called “Lake Effect” considers how the environment coexists and contends with human life:

[…] We don’t ask,

where’s the sea? We can walk to it,

and to acres of scrub, pasture, crop,

asphalt draining to it, and the reactor

it cools.

Signs of human change to the environment appear to be inescapable.

Yet, the splendor of the natural world heartily persists in Swan’s poems, and many lines admire this place where we reside, as the poem “Aubade” declares near the end of the collection:

It is good to […]

[…]

look out into

the lemon light of morning and

call it beautiful […]

Swan will read and be in conversation with poet and teaching artist Holly Wren Spaulding in a virtual event Tuesday, October 6, at 7 pm through Literati Bookstore. I interviewed Swan, a teacher at Western Michigan University, about ecopoetry, the Bentley Historical Library, and what she's reading.

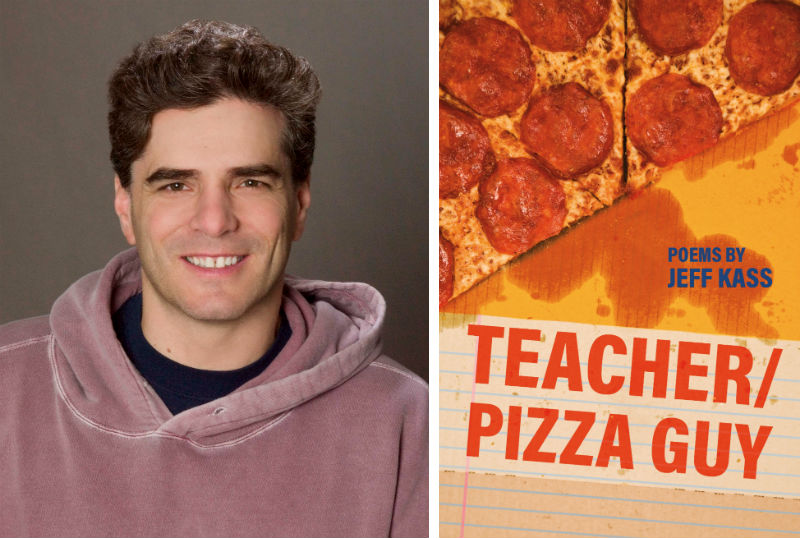

Author and A2 Pioneer Instructor Jeff Kass Contemplates the Working Life in "Teacher/Pizza Guy"

This story originally ran September 3, 2019. Kass is also author of the Fifth Avenue Press book "Takedown," a murder mystery. AADL cardholders can download the novel in PDF format here.

What do you do?

It’s what people ask when they first meet as a way to identify each other, yet our jobs do not have to define us.

When I asked Jeff Kass this question, he answered with three jobs: a full-time English teacher at Pioneer High School in Ann Arbor, part-time pizza delivery person, and part-time director of literary programs at the Neutral Zone for a year in 2016-2017. During that time, he also worked on drafting the autobiographical poems about this experience that form his new collection, Teacher/Pizza Guy (Wayne State University Press).

Teacher/Pizza Guy reveals Kass’ experiences in the classroom and pizza place, including issues with service industry jobs, challenges of aging, and relationships with colleagues, youth, and family. Despite the possible mundanity of work, Kass offers poetic insights on the situations. The first poem in the collection, “Oh, Splotch of Blue Paint,” not only addresses the paint on the sidewalk outside of the school where Kass teaches but also ruminates about its origins:

…were you trying to paint the sea? A place

for you to float in? The breeze a lovely, reassuring

friend who brings you cookies and iced tea

and listens to you without judging…?

This speculative question, in turn, raises a question for me: Isn’t that what we’d all like, a pleasant place, a friend who shares treats, and good conversation? Another poem depicts colleagues crossing paths in the night as Kass returns to home from his pizza-slinging job to see a fellow pizza slinger working his other job of delivering newspapers.

Amidst dishwashing, disastrous delivery runs, and the grind of teaching students in class after class how to write essays, Kass pulls out moments of clarity that describe the working life. One poem describes a break during which he makes a pizza for himself, one that’s not on the menu, and writes, “Believe / for a moment / your time / belongs / to you. / Savor. / Chew.”

Within the drudgery of going from job to job, Kass is not all work; he observes and shows parallels between his jobs and life, recognizing and taking ownership of those moments rather than letting work consume him, almost as if he is both living his life and watching it from the outside. Kass finds meaning in those fleeting moments of entering and exiting customers’ lives to bring them pizza and also seeks respect as he makes ends meet.

Kass, who lives in Ann Arbor with his wife, Karen Smyte, and their children, Sam and Julius, will read from his collection at Literati Bookstore on Tuesday, September 10, at 7 pm. I interviewed him about his poetry and work.

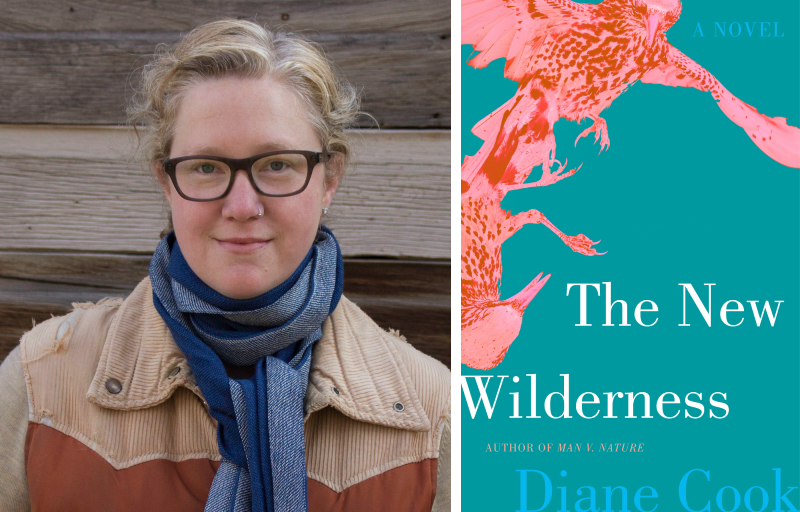

Diane Cook's novel "The New Wilderness" envisions a world after extreme climate change

Imagine being dropped off in the wilderness, uninhabited except for 19 people with you and rangers who patrol the land. Modern amenities are nonexistent, but the upside is that the air quality is much better than the polluted city. You live nomadically and hunt, fish, and gather to survive. This is not an extended camping trip. It is your new way of life.

This intense scenario forms the premise of Diane Cook’s new book, The New Wilderness, a speculative novel involving relationships and the environment—and how the latter influences the former. The novel has landed on the long list for the Booker Prize. Cook has taught for the University of Michigan, is a U-M alum, and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

In a joint virtual event, both Cook and Karolina Waclawiak, whose new novel Life Events was just published, will read and discuss their new books through the At Home with Literati series Monday, August 31, at 7 pm.

The characters of The New Wilderness, including Agnes, her mother Bea, and her mother’s husband Glen, go to the wilderness as part of a research experiment to determine whether this lifestyle is sustainable. Bea joined to save Agnes’ life. Agnes was five years old when they arrived and gravely ill from the effects of pollution. Despite learning how to stay alive in the wild and improving Agnes’ health, the characters’ memories of their former life, their love for one another in all its forms, and the burden of subsisting clash and inform their individual choices.

Early on, Bea’s concerns emerge when considering their next journey to a ranger post farther than they’ve had to go before:

Glen hooked his arm around her neck and pulled her close. “Now, now,” he murmured. “This will be fun.”

She knew that a big part of Glen believed this. But no part of Bea did. She pictured the map in her head again and saw all that unknown land, that beige parchment, all that nothing. They would be changed on the other side of it, that much she knew. Not knowing how was only one of the things that scared her.

The New Wilderness calls into question what the natural world is and should be, while also showing how vast the wilderness within and between people can be.

I interviewed Cook about this book and her writing.

Female protagonists populate U-M MFA graduate Sara Schaff's new collection of short stories

What you have. What you want. What you hang on to. What you give up.

Jeans. A house. A spouse. Drawings. Places. Jobs. A fantasy.

Sara Schaff’s second collection of short stories, The Invention of Love, invests in these questions of possession and ownership, of affiliation and surprising loss. The best way to understand the characters’ distinct circumstances and the fine lines between one version of their life or another that they choose, or that gets chosen for them, is by looking at the plots themselves. For example, two half-sisters lose their mother, and both covet her pair of jeans used for dancing in “Our Lady of Guazá.” In another story called “Noreen O’Malley at the Sunset Pool,” Noreen must let go of the narratives about her friends and lovers that she hoped for as she cares for her new baby.

Still, a character may make a delightful discovery amidst a seemingly unbearable situation, such as a woman eventually becoming enthralled by Anna Karenina despite the fact that her ex-husband’s new wife (and their family friend) had been the one who recommended the book. These observant views of these women show their realizations and complicated hardships as they navigate life and its turns.

Schaff will speak with Greg Schutz, writer and lecturer at the University of Michigan, in an At Home with Literati virtual event on Tuesday, July 21, at 7 pm. Schaff and Schutz are friends and fellow graduates of the MFA program at the University of Michigan. Information to join via Zoom is on the event webpage. We corresponded via email beforehand, and here are my questions and Schaff’s responses.