Designer Aaron Draplin brings Portland style to Ann Arbor

Fresh off his appearance at this year’s TEDxDetroit conference, prolific graphic designer (and Michigan native!) Aaron James Draplin will be bringing his powerhouse personality to the downtown Ann Arbor District Library on Friday, October 7, for a special mid-day talk that will start at 12:30pm.

Draplin’s passion for creating “good work for good people” combined with his bold independence is infectious and inspiring. You may have seen his work in any variety of short videos posted in recent years, like this logo design challenge (Vectors are free!), or his Skillshare classes, or his fantastic critiques of signage and design.

Based in Portland, Oregon, Aaron has been the sole proprietor of the Draplin Design Company since 2004. His clients range the full gamut from friends selling hot dogs (Cobra Dogs), Nike, Burton Snowboards, Esquire, Red Wing, Ford Motor Company, and the U.S. Government / Obama administration’s 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and the USDOT TIGER program.

In addition to his client work, he has generated a massive amount of “merch” in his personal projects including retro-inspired Space Shuttle posters, “thick lines” posters, and “Things We Love” State posters. His collaboration with Jim Coudal produced the well-known Field Notes brand, inspired by the kinds of memo books used by farmers (and a product of his passion for “goin’ junkin’” and “rescuing stuff”).

Expect some robust storytelling about his career and the creation of his first book, Draplin Design Co.: Pretty Much Everything. From the contracts to the scheming, from the pagination to the design, from the tears to the nightmares, he’ll tell you what it’s like to cram your whole half-wit design career into 256 pages and live to tell the tale. He'll pack in stories from the run-up, release, and surreal fallout, as well as updates to other tricky ventures the DDC has been up to.

After Aaron’s whirlwind mini-tour of Southeast Michigan, he will be embarking on a national book tour in support of the book. Pretty Much Everything is a jam-packed, in-your-face retrospective of his work so far, including drawings that give insight into his inspiration and process. In addition to the work itself, you get stories, commentary, and priceless advice in Aaron’s distinctive voice about what drives him and his work. It’s a must-have book for any designer.

Draplin’s relentless pursuit of creativity is sure to give you a swift kick in the pants to get out there and do great work. Leave work for an early lunch and then head over to AADL to jumpstart your weekend at an event that is not to be missed.

And if that’s not enough, his entire presentation is dipped in his signature color—Pantone Orange 021.

Amanda Szot is a graphic designer at AADL, and will likely have to breathe into a paper bag when introducing Aaron at his talk on Friday. She’s that excited.

Aaron Draplin will be at the AADL Downtown Library, 343 S Fifth Ave, on Friday, October 7 at 12:30 pm. This event (like all library events) is free of charge.

TAKESHI TAKAHARA: IN LOVE WITH THE PROCESS

KA Letts (of RustbeltArts.com) has written a great review of the WSG Gallery's current exhibition.

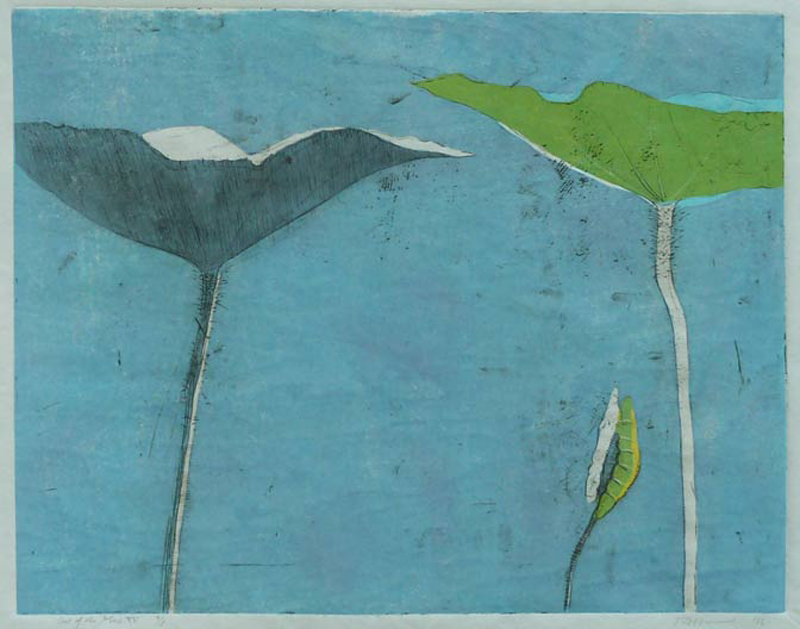

"Takeshi Takahara believes in the handmade, the one-of-a-kind, the idiosyncratic. This might seem a counterintuitive attitude in an accomplished master of intaglio printmaking, a medium which embodies the aesthetic of the multiple and reproducible. But in his first solo show at WSG Gallery he demonstrates that his unique, eco-friendly hybrid intaglio/woodcut process for creating small print editions (often only 5 to 9 per title) can deliver artworks that pack all the punch of a one-of-a-kind painting. Imperfection, a meticulously curated and well arranged grouping of prints on the theme of the lotus, is on view in the WSG gallery from now until October 22."

Visit RustbeltArts.com to read the review in its entirety.

K.A. Letts is an artist and art blogger. She has shown her work regionally and nationally and in 2015 won the Toledo Federation of Art Societies Purchase Award while participating in the TAAE95 Exhibit at the Toledo Museum of Art. You can find more of her work at RustbeltArts.com.

Imperfection will run at the WSG Gallery, 306 S. Main Street, through October 22, 2016. The WSG Gallery is open Tuesday-Thursday, noon–6 pm; Friday-Saturday, noon-9 pm; and Sunday 12-5 pm. For information, call 734-761-2287.

Review: Re: Formation at the Ann Arbor Art Center

The Ann Arbor Art Center’s latest exhibit is the Re: Formation to help begin all reformations.

As the exhibit’s statement tells us, the display “examines this unique moment [in history] when ordinary people are declaring a la Peter Finch [from Sidney Lumet’s 1977 film Network]: “‘I’m mad as hell and I won’t take it anymore.’”

This is indeed the precise sentiment of this unceasingly clever exhibit of art.

For Re: Formation, the latest offering of Rocco DePietro and Gloria Pritschet, founders and directors of the Gallery Project, follows suit with this artful duo’s willingness to go where most other forums fear to tread. Ann Arbor's Art Center exhibit pairs with an earlier August incarnation of the show exhibited through the auspices of Toledo, OH’s Art Commission.

As the exhibit statement continues, “What is different at this time is that people who have been silent, or silenced, are standing up, speaking out, and mobilizing for needed change. Highly divergent in life styles with broad-ranging backgrounds, beliefs, and values, these individuals are expressing justifiable anger at the accumulation of horrific events and unrelenting injustices that characterize our current era.

“They are teaming up across race, gender, politics, and social status with empathy and compassion for their fellow human beings. Their actions are reestablishing belief in a positive future based on fairness, equity, and genuine possibility for all.

“Is this a tipping point, a moment for reform, or even a revolution? Or is it just another blip before capitulation and regression?”

These are, of course, highly potent questions. The very nature of this articulation will be considered by some as transgressive. But the paradox, of course, is that the very nature of the contention leaves motivation and avocation hanging equally in the balance.

Because of course, the definition of art itself is being challenged in Re: Formation. What is the purpose of art? Is it meant to merely have a decorative function? Or is it meant to provoke and challenge one’s preconceptions?

The Gallery Project is letting us know what they think, and towards this end DePietro and Pritschet have mobilized a formidable array of national, regional, and local talent whose outlooks cut across a whole host of social, political, and cultural viewpoints. There are (to borrow from a questionable cliché) no sacred cows here. And even if there were, it would be just as many of the artists on display who would want to devour it as there are others who would hold it sacred.

Local talents on display are Ann Arbor’s Heather Accurso, Morgan Barrie, Carolyn Barritt, Ruth Crowe , K.A. Letts, Melanie Manos, Michael Nagara, Sharon Que, Jesse Richard, Meagan Shein, Ellen Wilt and Richard Wilt. Dexter is represented by Tohru Kanayama; with participation by Ypsilanti’s Nick Azzaro and Jessica Tenbusch.

Among the works on display, Azzaro gives us a potent taste of Re: Formation’s disposition. His unframed “Progress at the Ol’ Smith Furniture Building” color photograph touches on all the ideas stated in the exhibition’s gallery statement.

There are, of course, Americans who to this day think of the Confederate States of America’s second Battle Flag as a sacred totem of historic significance with as much a symbolic value as the United States’ stars and stripes. Indeed, these stars and bars—in either its peace or war confederate configuration—are still part of the symbol (and considered a venerated heritage) in parts of the American south and officially designated in three southern states.

But the flag is also a highly potent symbol of a heritage that is itself emblematic of one of the most controversial aspects of our republic’s heritage. Representative of the defense of slavery as a political institution, the Dixie Battle Flag serves as a visceral reminder of attitudes that cut across economic, social, and cultural lines. As such it’s not uncommon to find the flag on private property such as flag pole or car—now often in a setting that is seemingly as much defiance as it is supportive.

Thus Azzaro’s photograph transgresses these values by vividly appropriating the symbol and subverting its erstwhile significance. Running across a dilapidated storefront with this flag in flames, “Progress at the Ol’ Smith Furniture Building” is a straightforward, aggressive recasting of social, economic, political, and cultural American expectations.

Just like many other artworks on display in this highly emotionally charged exhibit, if Azzaro’s “Progress at the Ol’ Smith Furniture Building” isn’t a Re: Formation of American expectations, it’s hard to imagine what might be.

John Carlos Cantú has written on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

Re:Formation will run through October 8, 2016, at the Ann Arbor Art Center, 117 W. Liberty St. Exhibit hours are 10 am to 7 pm, Monday-Friday; 10 am to 6 pm, Saturday; and noon to 5 pm, Sunday. For information, call (734) 994-8004.

Interview: Mark Mothersbaugh on Pee-Wee Herman, Thor, and America's ongoing de-evolution

Mark Mothersbaugh is best known for his indelible contributions to pop music as the frontman of Devo, but his work with the darkly humorous New Wave group represents just a fraction of his diverse artistic output. Since the late '80s Mothersbaugh has composed music for hundreds of movies, TV shows, video games, and commercials. His visual art includes thousands of pen-and-ink postcard-sized drawings, rugs, sculpture-like musical instruments, and eyeglasses. This broad body of work, including the music and early music videos he created with Devo, is the subject of a new traveling museum exhibit, Mark Mothersbaugh: Myopia. The exhibit currently is not scheduled to stop in Ann Arbor, but in a way we'll be getting something even better. Mothersbaugh will appear at the Michigan Theater on September 29 for the Penny Stamps Speaker Series, engaging in conversation with Adam Lerner, who curated the Myopia exhibit and wrote the accompanying book.

In advance of his Ann Arbor appearance, Mothersbaugh chatted with Pulp about maintaining a sense of subversiveness despite corporate interference, his enduring friendship with Pee-Wee Herman creator Paul Reubens, and Todd Rundgren's enviable fashion sense.

Q: You'll be in conversation here at the University of Michigan with Adam Lerner, who curated the new retrospective exhibition of your work and edited the accompanying book. As you've had these opportunities to look back on your work recently, have you had any new realizations about your evolution as an artist over time?

A: [Laughs.] You know, yeah. You do pick up information along the way of being a human, I've found. To me, when I walk through the show ... it's kind of interesting to see what things are the same and what things never change. When I look back at the arc of all my visual art, I can say, "Well, in a way it's permutations on a theme." It really goes back to when I was at school at Kent State. I hated public school. The first 12 years of my life in school were horrid. I was at odds with other students, with the teachers, with everybody. It was just totally unpleasant and I almost ended up at Kent State on a fluke, but it turned out to change my life in a lot of ways. I gained a respect for education, among other things, and I just loved having access to tools that I never had access to before ... There was very limited art teaching in public schools in the '50s and '60s, so it was kind of this amazing world that got opened up to me when I all of a sudden found out about all the things you could do, all the empowerment that came with being in college. I loved it.

But at that time period, I was there for the shooting of the students at Kent State. We had all joined [Students for a Democratic Society] and we were going to help end the war in Vietnam and then things took a dark turn. ... That was in my sophomore year, and [I was] questioning that. I was collaborating for about a year before that with a grad student that was an artist at Kent State named Jerry Casale. Questioning what we'd seen, we decided that what we'd seen was de-evolution, not evolution. I understand that there's different ways for artists to evolve and mature and to fall apart or to build. I think in my case, I think my life as an artist has always been kind of seen through the eyes of someone that was always kind of hopeful, but paranoid at the same time. Or worried about it. Hopeful, but concerned. We saw de-evolution as a vehicle to talk about the things that we were concerned about on the planet, and I feel like my work has been sort of permutations on that theme.

Even kind of shifting into the belly of the beast and moving into Hollywood and scoring films and television, between Devo kind of slowing down at the end of the '80s, I started doing gallery shows. I did about 125 or 140 shows at mostly smaller pop-up galleries and street galleries, just because being in Hollywood made me distrustful of organized entertainment, so to speak. I've found all the smaller galleries to be, a high percentage of them, filled with authentic people that loved and were concerned about art and reminded me of what it was like to be in Devo when we were starting it. We thought we were doing an art movement. We thought we were doing Art Devo. We were like an agitprop group who worked in all the different mediums and were spreading the good news of de-evolution around the world. That was our original goal.

When we signed with Warner Bros. and Virgin Records, they kind of did as best a job as they could of shoving us into a little box that they could understand. ... Even in the late '70s, it was a struggle to convince them to let us make our short films. They had no idea why we wanted to make films with our songs. There were so many things that were a struggle that were needless. As Jerry would say, we were the pioneers who got scalped. But it was like the early days of people recognizing artists that put ideas in front of the actual techniques that they used. A technique was just a vehicle to help you solve a problem or create a piece of art. Being a craftsman was less necessary than ever before in our culture.

Now it's totally amazing how far it's gone. Kids that have ideas now about art, they don't have the barriers that we had or I had. The Internet is such an amazing, wonderful gift and tool for kids. I'm so jealous I'm not 14 right now. I watch my kids – they're 12 and 15, and I watched them make little movies on an iPad when they were even younger. It's totally transparent to them and they're laughing and running around the house. They're making a movie like a little kid would make, but they don't even know that 30 years ago – was it 30? '76, that's like, what, 40 years? Jesus. Forty years ago. It took a year of work first to make the money to pay for $3,000 worth of material and then to find time in editing bays where we could go in and make our seven-and-a-half minute film. And it's not just my kids. It's all over the world. Cell phones and iPads, things like that, are so inexpensive now that you see kids in the Amazon playing with this stuff, taking pictures of things around them and making music on iPhones. You not only don't have to own a guitar or a piano or a set of drums. You don't even have to know how to play it. My kids found this app where they could play drums by just making drum sounds into their phone and it would translate that into one of 30 different drum kits. ... Art has become so democratic. On some levels it's astounding. Anyhow, I don't know how I got to that after you were asking me about my art, but there you go. That's the danger of talking to me after a cup of coffee.

Q: That's okay. It was an interesting answer. I want to ask you a little bit more about the concept of de-evolution, since that was of course so important to the formation of Devo. How has that concept played out for you as time has gone along? Do you see de-evolution continuing to play out? Is that concept still as relevant to you as when you were younger back in the '70s?

A: I think all you have to do is look at this current election season in the U.S. It's like Idiocracy has arrived, for real. It's not even ironic or funny anymore. It's reality. It's kind of impressive and depressive at the same time, because we were never in support of things falling apart or the stupidity of man getting the upper hand. We just felt like, if you knew about it and recognized it, you could be proactive and change your mutations carefully, choose them on purpose instead of just letting them be pushed on you and accepting them.

Q: I want to ask you about a couple of more recent projects. You most recently scored the new Pee-Wee Herman movie. Did Paul Reubens bring you back in on that project personally, and did you guys remain in touch in the decades since you worked on Pee-Wee's Playhouse?

A: It's kind of funny. ... Right when he was first creating the Pee-Wee Herman character, we'd already met. This was '70 – I don't know what, '70-something – and my girlfriend at the time, her parents, her mom was instrumental in starting a comedy group out in Los Angeles called the Groundlings. Her name was Laraine Newman. She was one of the original cast members for Saturday Night Live. She would take me to the Groundlings and I saw Paul while he was working on developing this character. We kind of knew each other and he had asked me to do his first movie, Pee-Wee's Big Adventure, but I was so deep into Devo and we were touring. I didn't do Pee-Wee's Big Adventure, but he called me up after that and said, "Well, okay, how about now? Would you do my TV show?" It just happened to be that Devo had signed a bad record deal with a record company that was going bankrupt. We were just like rats on the Titanic, along with about 20 other bands that were just sitting on the bow. It seemed like the perfect time to work on a TV show.

I'd been in this situation where I was writing 12 songs, rehearsing them, then go record them, then make a film for one or two of the songs and design a live touring show, and then we'd go out on tour and a year later we'd come back and write 12 more songs. When I started doing Pee-Wee's Playhouse they would send me a three-quarter-inch tape on Monday. Tuesday I'd write 12 songs. Wednesday I'd record them. Thursday I'd put it in the mail and send it to New York, where they were editing the show. Friday they would cut it into the episode of Pee-Wee's Playhouse for that week. Saturday we'd all watch it on TV. Monday they'd send me a new tape and I'd do the process over again. I was like, "Sign me up for this! I love the idea of getting to create more and write more music as opposed to spending all my time sitting around in airports waiting to get to the next venue."

So now, all these years later, [Reubens and I] have stayed friends. He's probably the only guy – other than my mom and dad, who are both passed away now – but he was the only other person who remembered every one of my birthdays and sent me something. That was kind of nice, even if we didn't see each other all the time. So we stayed friends and when this came up, it was kind of like coming around full circle to get to work with him again. I ended up recording the London Philharmonic in Abbey Road, which has kind of turned out to be one of my favorite studios. I've done maybe a dozen movies or so there. And I don't know if you saw the movie or not, but he does a pretty good job of looking like Pee-Wee did 40 years ago.

Q: He does, yeah. It's surprising. You're also scoring the upcoming Thor sequel. How did you get involved on that project and how much work have you done on it so far?

A: That's an odd one for me to talk about, and the reason is because I just happened to casually mention it in Akron. I was reminded that I had signed an NDA, a non-disclosure agreement, with Marvel, and most of the time what people are concerned about is they don't want you to give away the plot of the film. They don't want you to give away any spoilers or tell them any of the details of the movie before it comes out. Well, Marvel quickly picked up on that I had mentioned I was working with Taika Waititi, who is the director. I happen to really like his work. Somebody asked me if it was Thor and I said yes, and they reminded me that I'm not allowed to talk about the movie. So I either am or I am not working on a movie with this guy. He had a lot to do with attracting me to the project just because his movies are super-creative. I really liked his new movie, Hunt for the Wilderpeople. Musically, it's really creative. That's what really caught my interest.

Q: You've done so many different scores over the years, and you mentioned how much you enjoyed that way of working. What appeals to you about that kind of work? How much creative limitation do you feel that kind of work imposes on you and how do you respond to that limitation?

A: Much less than when you're in a band. The first couple albums with Virgin and Warners were great. They signed us just because they wanted the bragging rights of, "Brian Eno paid for this record to be recorded. David Bowie hung out with them in Germany the whole time they were recording it." [Bowie] had called us "the band of the future" in Melody Maker back before we had released anything, just based on tapes we had managed to get backstage to him while he was playing keyboards for Iggy on a tour back in '77 or '76. Where was I going with this story?

Q: I was asking you about creative limitations.

A: Yeah, the first couple albums they left us alone. Then we unfortunately had a radio hit and Warners then looked at us as gold. They had made a bunch of money off of us and then they started showing up at our rehearsals and our recording sessions. We'd be working on something and then some guy would pop up with a mullet and go, "Hey, do anything you want on this record, you guys. Feel free to do whatever you want. Just make sure you put another 'Whip It' in there!" And it changed our whole relationship with the recording industry, because where we enjoying being slightly anonymous and our feeling was that we were able to be kind of subversive, all of a sudden we had all this pressure and people commenting on our choices.

On that album that they were coming to listen to, we had done a cover version of "Working in a Coal Mine" and they fought to take it off the record. The record company pushed it off of our album. So we gave it to some movie called Heavy Metal, because we thought, "Oh, we're going to get a free ride with all these heavy metal bands when they put out their album. Our little weirdo song will get a free ride with Van Halen." We thought that was funny. Then that turned out to be the song that went into the top 20, so we pulled all these lame heavy metal songs along for a ride, which the joke was kind of on us. Then Warner Brothers panicked because right as they were about to release our new album, we had a record that was in the charts playing. They freaked out. They pressed singles with "Working in a Coal Mine" on it and stuck them inside the album as an afterthought. They just did the most nincompoop things.

So working in film and TV, you're much more anonymous as a composer. There's not a magnifying glass on you and you have so much more freedom. Pop music back then is the same as it is today. From song to song the variation is very small. It's like the fashion industry. There's like 50 pairs of the same jeans coming out from different manufacturers. The label's a little different, and some of them have a stitching thing where they put a loop in them, and then somebody else has one button that shows at the top of the pants, and then somebody else has a pocket that zips shut or something. But they're all exactly the same. It's all the same stuff. Pop music is like that to me and still is. So when I went into working on Pee-Wee's show, it was a whole different world. I could do punk hoedown music on one episode. I could do South Sea Islands goes into Ethel Merman with Spike Jones stylings in it for the theme song for the show. It was all wide open and I loved that so much, coming into this world now where you have such a wide palette. In so many ways it's superior. For me, I always had two brothers and two sisters, and Devo had two sets of brothers. So the idea of collaboration was always a part of my art aesthetic. I always liked to have people to collaborate with. So having a director that has ideas, and he tells you what he's trying to do with his film and you help him see that finally or you help him hear it, is very satisfying to me.

Q: You mentioned the broad range of creativity you were able to express through something like Pee-Wee's Playhouse. How do you manage to still express that broad range of creativity, or express that subversive element you mentioned earlier on with Devo, in some of the more conventional movies you've done, say a Last Vegas or something like that?

A: There's really super-literal ways to do that, if you have something you want to say or you want to talk about. Subliminal messages are so easy and nobody pays attention to them. [Laughs.] It's really funny. I remember the first time I was doing a Hawaiian Punch commercial. It was my first commercial and I was kind of not sure how I felt about doing TV commercials, but I liked the idea of being in that arena. It needed a drumbeat and I put, "Choose your mutations carefully." [Imitates drumbeat.] Bum-buh-buh-bum, bum-buh-buh-bum. And Bob Casale was my longtime engineer and coproducer on all this stuff. I remember we were in a meeting with Daley and Associates, the ad agency that was representing the commercial. We played the song and in this room I'm hearing, "Choose your mutations carefully." I'm looking at a guy over there tapping his pen on the table and as soon as the commercial ends I turn bright red and Bob Casale looks at me like he wants to kill me, like we're going to be in so much trouble. And the guy is tapping his pen and as soon as this commercial ends he goes, "Yeah, Hawaiian Punch does hit you in all the right places!" He just shouts out the main line from the narrator at the very end. We just look at each other and I'm like, "It's that easy?" We did it for years and then I got caught by a picture editor who said, "I know what you did." He called me out. He said, "I know what you're doing. You should take that out." I think I put "Question authority" in something like a lottery commercial or something, so this guy made me take it out. But the ad agencies never called me on it. And I even talked about it in articles before, and I still get hired by ad agencies to do commercial music. So they must not really care.

Q: So you haven't stopped that practice then?

A: Well, it depends. You have to have a reason to do it. Usually the more sugar that's in something, the better the chance that I'm going to say "Question authority" or "Sugar is bad for you." That's one I've done a couple of times. It's easy to do. They're easy to find, too. You can find them if you know which commercials you're looking for. You can look them up. And you hear it, too. Once you know that it's there, then you hear it. If you don't know it's there, your mind doesn't want to make it happen. It just goes in there like malware. What's the opposite of malware? What if it's there to help you out? I guess that's an antibiotic. It's like a covert antibiotic.

Q: A probiotic?

A: Yeah, probiotic. That's it! It's a probiotic.

Q: You certainly have plenty of non-Devo work going on and have for a long time, but Devo also still gets out there and tours from time to time. How do you feel about the band's role in your life these days?

A: I only have one really big problem with the band, and that is that we still play as loud as we did when we were onstage in Central Park or at Max's Kansas City or whatever that place was that we played in Ann Arbor. I think it was a bowling alley. I can't remember. It was some stage where it had a proscenium around it that looked like a TV screen. ... What I remember about that night also ... is that Todd Rundgren had shown up to see the band and he had a suit made out of tan oilcloth plastic. I was like, "How did he get that done? That is so awesome!" I remember being so jealous of this suit that Todd Rundgren was wearing. While we were talking I just kept staring at his suit the whole time and then looking around to see if I could tell if it was possibly a commercially made thing, which it wasn't, I'm sure, in retrospect. But it was the first time I'd seen a tailored suit made out of plastic. [Mothersbaugh likely recalls Devo's 1978 show at the Punch and Judy Theater in Grosse Pointe Farms in 1978, which coincided with a Rundgren show in Royal Oak.]

Q: You were saying, then, that today your only problem with the band is that you play as loud as you did back in the day?

A: Yeah, we play so loud and I have tinnitus. It's hard for me to go play 10 shows in a row with Devo and then go back to my studio and try to listen to the woodwinds from an orchestra. It takes me like a week or so for it to calm down enough that I can go back to work. It's not worth the tradeoff for me to go deaf just so I can play 50 more Devo shows, to be honest with you. We'll do one here and there. We did a benefit earlier this year. Will Ferrell talked us into it. It was like the worst thing for me because I'm standing onstage and they're wheeling all these drummers out onstage. Part of the thing was a joke that they had 12 drummers all at once, so not only did they have my drummer, but Mick Fleetwood was onstage and Tommy Lee was onstage. They were all playing simultaneously, like a dozen drummers, the Chili Peppers drummer and all these. I'm standing there going, "This is the worst thing that could have possibly happened." I went home from that and it was like gongs were going off in my head. So that's the thing that makes Devo where I have to draw a line. I can't do a big tour again.

Q: So if you're going to be onstage these days you'd rather be doing something like you will be here in Ann Arbor, where you're just having a quiet conversation onstage.

A: Preferably. Yeah. That's totally different. And all I ask is that people in the audience ask questions. Speak clearly.

Patrick Dunn is the interim managing editor of Concentrate and an Ann Arbor-based freelance writer whose work appears regularly in Pulp, the Detroit News, the Ann Arbor Observer, and other local publications. He exercised considerable restraint in asking Mark Mothersbaugh about anything other than Pee-Wee Herman.

Mark Mothersbaugh will appear at the Penny Stamps Speaker Series Event, presented by the Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design at the Michigan Theater, 603 E. Liberty, on Thursday, September 29 at 5:10 pm. Free of charge and open to the public.

UMS Artists in Residence 2016-2017 Announced

The theme of the 2016-2017 UMS Artists in Residence program is "renegade art-making and art-makers" and the artists have just been announced. According to the announcement, the "five artists (including visual, literary, and performing artists) have been selected to use UMS performance experiences as a resource to support the creation of new work or to fuel an artistic journey."

The artists for 2016-2017 are:

Simon Alexander-Adams - a Detroit-based multimedia artist, musician, and designer working within the intersection of art and technology.

Ash Arder - a Detroit-based visual artist who creates installations and sculptural objects using a combination of found and self-made materials.

Nicole Patrick - a musician and percussionist who performs regularly with her band, Rooms, and other indie, improvisation, and performance art groups around southeastern Michigan.

Qiana Towns - a Flint-based poet whose work has appeared in Harvard Review Online, Crab Orchard Review, and Reverie, and is author of the chapbook This is Not the Exit (Aquarius Press, 2015).

Barbara Tozier - a photographer who works in digital, analog, and hybrid — with forays into video and multimedia.

Congratulations to these artists - and look for blog posts and engagement with the artists throughout their term on the UMS site.

Preview: POP-X AAWA Installation

The second annual Ann Arbor Art Center community festival and art extravaganza POP-X is set to open on September 22. This multifaceted, multi-disciplinary, multi-artist event will run for 10 days and 10 nights in 10 pavilions right downtown in Ann Arbor's Liberty Square Park.

Each pavilion features the unique vision of an artist or art collective, ranging from poetry to video to floral installation to caricature. There's even a mini-pub serving craft beers, and as if that weren't enough, the spaces outside the pavilions will feature art demonstrations, musical performances, social gatherings, panel discussions and participatory art making throughout the run of the festival, which ends October 1.

The goal of POP-X is to present work that actively engages the community, and this year’s POP-X artists have interpreted this in their own unique ways. Ann Arbor Women Artists, a 300 member non-profit artists' organization, has chosen to implement this vision in the broadest possible way, designing and executing a comprehensively inclusive art installation that cuts across barriers of age, gender, race and disability. Their art installation, Side-by-Side, is the result of many collaborative art-making sessions where professional artists were paired with non-professionals to create the painted faces that will fill the AAWA pavilion on September 22. Project partners range from the very young children of En Nuestra Lengua to the high schoolers of Girls Group, to seniors of the Silver Club and residents of Miller Manor, an apartment for the disabled, and others. Ann Arbor Art Center President and CEO Marie Klopf attended a session held at the Art Center, as did Omari Rush, their Director of Community Engagement. Three City Council Members, Sabra Briere, Chuck Warpehoski and Julie Grand also took time from their busy schedules to be part of the project.

"Our plan was to reach out to individuals in the Ann Arbor Community, despite on-the-surface differences, and to create an art installation which honors both our unique individuality and our shared humanity," –Elizabeth Wilson, Lidia Kaku, Mary Murphy (co-chairs).

Community arts projects are a strange, hybrid beast, part crafts project, part encounter group, part social club. The success or failure of any project of this kind depends on the planning and design of the installation and its constituent parts. The faces made by artists and their partners will be mounted on a framework on the interior walls of the pavilion, with mirrors incorporated to allow visitors to see themselves in the installation. A sound loop of music will be interwoven with short clips of conversations from pairs talking about the work they are doing and discovering more about each other in the process.

Barbara Melnik Carson, a core member of the working group, maintains that Side-by-Side has been the best example of cooperative art-making in her wide experience. "Everyone worked so well together–there were no egos getting in the way, which isn't always the case," she says. "Each member of the core group has different strengths, and they have all had an opportunity to contribute in their own way."

The members of the project Side-by-Side don't see the completion of this installation as a mission accomplished. They see it as a pilot project for an ongoing community engagement program which would organize citywide pop-up events with the purpose of building lines of communication throughout Ann Arbor.

"We plan to bring the whole world together one portrait at a time," says Barbara Melnik Carson.

K.A. Letts is an artist and art blogger. She has shown her work regionally and nationally and in 2015 won the Toledo Federation of Art Societies Purchase Award while participating in the TAAE95 Exhibit at the Toledo Museum of Art. You can find more of her work at RustbeltArts.com.

POP·X runs Thursday, September 22 – Saturday October 1, 2016 from noon to 8pm at Liberty Plaza Park, 255 East Liberty St., Ann Arbor. To learn more visit popxannarbor.com or the POP•X Facebook event page. POP•X is free and open to the public.

For more information about Ann Arbor Women Artists, visit their website.

AAWA POP-X Committee Members are: Elizabeth Wilson (co-chair), Lidia Kaku (co-chair), Mary Murphy (co-chair), Barbara Melnik Carson, Barbara Bach, Barb Maxson, Joyce Bailey, Lucie Nisson, Marie Howard, Susan Clinthorne, and Sharon St. Mary.

Review: "Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light," University of Michigan Museum of Art

The University of Michigan Museum of Art’s Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light is easily going to be one of the most accurate art exhibition titles of 2016. This tidy 23-piece UMMA display shows the world-famed Bravo at his best: For he’s indeed a master of photographic light—as well as a poetic artist.

All photographers are capable of what is sometimes called a “privileged moment.” After all, it would seem simple enough to capture a moment with photography: You just point your camera and click.That's what's been happening photographically for quite nearly this last 150 years ... right?

Well, not quite. After all, you have to know what you're looking for because the most remarkable thing about photography is the camera’s utterly elastic way of recording an image. The world isn't as transparent as might seem apparent on first observation. And it doesn’t take much more than one’s last batch of photos for the confirmation.

Bravo, on the other hand, knew what he wanted to see—but the craft didn’t stop there. For the next rule consists of mechanistically knowing how to get what you want to see. And this is as complicated a task as knowing what one’s looking for.

It’s at this point that poetry arises—and was Bravo ever a masterful poet.

He’s easily one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century. For this poetry is, of course, the magic of all the world's greatest photographers. Like a mechanistic fingerprint, no two photographic styles are ever really the same. Time, space, intuition, and the very act of looking all mark the poetry latent in the photographic medium.

One glance at Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light and it's obvious Bravo knew what he was looking for. Each Bravo artwork in this magnificent exhibit is an extraordinarily well thought-out composition where every visual element is accounted for; these physical elements being weighted against the tone of light, the density of light, the direction of light, the volume of light—and then there’s the poetry.

What’s left in the image is the world unto itself.

Granted, the time in which Bravo was working is romantic. Mid-20th century Mexico was a world where the natural and the supernatural seemingly melded together in a heady exotic brew and where the sacred and the profane coexist comfortably. There’s seemingly no separation between what is well and what is well-enough.

Born into an artistic Mexican family, Bravo was forced to terminate his education at the age of 12 when his father died in 1914. Studying accounting as he worked for the Mexican Treasury Department, Bravo freelanced photojournalism while learning the basics of art photography. It was through the friendship of fashion model and political activist Tina Modotti that he made contact with American photographer Edward Weston who in turn encouraged him to polish his craft.

Having lived through the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920, Bravo was inclined to view his art through the prism of natural supernatural romanticism (and later surrealism) that marks early 20th-century Mexican aesthetics. As can be seen in the photographs of this exhibit, Bravo wrestled with the stereotypes that stamp much Mexican artistry while often using echoes of this stylization to comment upon them. Bravo's camera consistently catches these contradictions with a fluid grace that never editorializes while knowingly commenting on what’s depicted.

This means that every element of Bravo's photography is weighted against the composition's visibility as well as the reflection of Mexican culture as he lived and understood it. The result is indeed sheer poetry cum anthropology, as none of these photographs are never quite what they appear.

For example, Bravo’s 1977 gelatin silver print Señor de Papantla (“The Man of Papantla”) is a decidedly clever photograph whose background and meaning are richer than apparent in the already rich photograph of a Mexican campesino dressed in his best peasant garb. For the locale of the painting is as important as the image in that Papantla (in the state of Vera Cruz; in the Sierra Papanteca range, near the Gulf of Mexico) is famed as one of Mexico’s “pueblo mágico”—a city of particular natural beauty with historic and cultural relevance.

Bravo’s Señor stands stiffly with his sombrero tucked under his right arm posed in front of a nondescript stone wall. Standing under the diagonal right shade of a tree with his hair parted in the same direction to create an internal symmetry, of equal importance is his eyes cast away to the left in the same way. Averting the photographer’s gaze, Bravo’s Señor reflects the subdued unwillingness to cooperate that’s often characterized the citizenry of a country that’s seen centuries of repetitive political, social, and cultural upheaval.

By contrast, famed Mexican artist Frida Kahlo adopts an opposite stance for Bravo’s camera in her 1938 Frida with Globe, Coyoacan, Mexico gelatin silver print. Where the campesino was not directly addressing the camera, Kahlo challenges the camera by looking directly at Bravo. This act, of course, is in direct contrast to the Mexican sense of social propriety where the expectation would decidedly be a repressed feminine averral.

Even in the late 1930s, Kahlo (and by extension, Bravo) were having none of this modesty. Sheer appropriateness is drawn from her forthright respectability, as though the appropriateness of one’s behavior is as much one of correctness as it is self-respect. Seated with her left elbow propping her left hand against her cheek, Kahlo is everything she intends to be.

But Bravo is also addressing his audience in that a single subtle compositional element twitches the history of art anachronistically. For in contrast to Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas (where Velázquez paints himself painting the painting), Bravo eliminates himself from his photograph because there is no photographer reflected in the globe on the table next to Kahlo’s left. Surrealism was, of course, in full force in Europe at this time and Bravo opts to magically disappear in his own artwork.

If, however, one wants to find Bravo at the height of his power as a photographer, his famed 1932 gelatin silver print Retrato de lo eterno (“Woman Combing her Hair”) seals the deal. The exact translation of the title is “Portrait of the Eternal” and while the more prosaic “Woman Combing her Hair” is certainly accurate, the fantastic inference of “Portrait of the Eternal” is more enduring.

As I noted in the September 2002 UMMA Manuel Álvarez Bravo: 100 Years exhibition, Retrato de lo eterno captures Bravo at his haunting best. This darkly handsome portrait—of yes, a woman combing her hair—is everything its title says. Yet it’s also far more, as Bravo’s key lighting in this black and white photograph boldly exposes the model’s profile while also draping her in a controlled chiaroscuro where graded shadows create layer upon layer of profound mystery. The model’s self-absorbed beauty is veiled in an eternal mist.

Bravo’s Retrato de lo eterno is as much a staggering a work of genius today as it was in 2002. Just consider us lucky to look upon her likeness once again after fifteen years. If only because she’s indeed a portrait of the eternal—and this portrait will be so for a long time to come.

John Carlos Cantú has written on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

University of Michigan Museum of Art: “Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light” will run through October 23, 2016. The UMMA is located at 525 S. State Street. The Museum is open Tuesday-Saturday 11 am–5 pm, and Sunday 12–5 pm. For information, call 734-764.0395.

Preview: The University of Michigan Museum of Art's "Nights at the Museum"

Nights at the Museum, the University of Michigan Museum of Art's exterior media arts initiative, will illuminate the museum's facade with artwork, performances, and family-friendly movies from September 2 - 9.

Events are open to the public and will run each night from 8:30 pm to dawn along its State Street-side facade, on the west side of the Maxine and Stuart Frankel and the Frankel Family Wing.

A digital art installation by Quayola titled "Pleasant Places" will be projected overnight, from dusk to dawn, on Friday, Saturday and Sunday. From Tuesday through Thursday, UMMA will collaborate with U-M arts partners, including the University Musical Society, Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design, and School of Music, Theatre & Dance, with each organization showcasing a related video performance or art installation.

Here's the full schedule:

Friday, Sept. 2

7 - 10 pm: Artscapade!,/a> a Welcome Week events for students

10 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Saturday, Sept. 3

8:30 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Sunday, Sept. 4

8:30 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Monday, Sept. 5:

8:30 - 10 pm: Family-friendly movie night with a screening of Toy Story

10:15 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Tuesday, Sept. 6

8:30 - 10 pm: Performances by U-M School of Music, Theatre & Dance students and faculty, including the Men's Glee Club, University Symphony Band, University Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Choir. Love, Life & Loss, a 30-minute film featuring the Michigan Men's Glee Club performing "The Seven Last Words of the Unarmed," will kick off the performances.

10:15 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Wednesday, Sept. 7

8:30 - 10 pm: Short art films created by U-M Penny W. Stamps School of Art & Design faculty and students, including:

Zoe Anderson (BFA 2007): "Little Luminaries"

Ashley Bock (BFA 2018): "Fission"

Alexa Borromeo (BFA 2016): "Stay Out of the Sun"

Shane Darwent (MFA 2018): "Orquesta de las Calles"

Niki Horowitz (BFA 2016): "Personal Projections"

Carol Jacobsen (Stamps professor): "Prison Diary"

Andy Kirshner (Stamps associate professor): "Liberty's Secret" (segment)

Rebekah Modrak (Stamps associate professor): "Re Made Best Made Echo"

Zoe Brendan Widmer (BFA 2016): "Does My Undercut Make Me Look Queer?"

Niki Williams (BFA 2016): "Grimestone"

10:15 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Thursday, Sept. 8

8:30 - 10 pm: Screening of Snarky Puppy's Family Dinner-Volume Two in collaboration with UMS. (Snarky Puppy is a Grammy Award-winning "quasi-collective" that will perform at Hill Auditorium March 17, 2017.)

10:15 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Friday, Sept. 9

7 - 10 pm: UMMA After Hours

10:15 pm - 7 am: "Pleasant Places" installation by artist Quayola

Preview: DIYpsi Summer Festival

As summer winds down and the nights grow shorter we find ourselves seeking out great outdoor events to attend to soak up as much summertime as we can. One such event to help send the month of August out with a bang is the DIYpsi Summer Festival, which takes place at ABC Microbrewery in Ypsilanti. This twice-a-year craft fair pulls out all the stops during its summer shows, as it continues to grow in size and amazingness each year. This not-to-be-missed show not only boosts the local economy and supports the arts, it combines so many elements to enjoy in one location, and this year they are going all out.

You’ll find over 80 top notch craft vendors from the Midwest selling superb handmade goods, as well as delicious foods on board, specialty craft brews, and a plethora of live music featuring local musicians that will be jamming out all weekend enhancing the already chill vibe. The organizers have some special treats in store this summer that include Theatre Bizarre working carnival games as well as a petting zoo at this indoor/outdoor extravaganza.

Between the crafts, food, beer, and a mini donkey, what more could you ask for in a summer weekend?!

Amanda Schott is a Library Technician at the Ann Arbor District Library and is a super mega ultra fan of craft fairs.

DIYpsi takes place at ABC Microbrewery (Corner) in Ypsilanti on Saturday, August 27 from 11 am- 8 pm (bands play until 11 pm) and Sunday, August 28 from 12 pm- 6 pm. Admission is a $1 suggested donation. The event is 21+ unless accompanied by a parent or guardian.

Review: "Catherine Opie: 700 Nimes Road," University of Michigan Museum of Art

The University of Michigan Museum of Art’s Catherine Opie: 700 Nimes Road is a star-studded two-for-one visual art spectacular. 50 photographs culled from over 3,000 taken in 2010-11 by Los Angeles-based photographer Catherine Opie at the residence of actress Elizabeth Taylor, the exhibit illustrates the six months this famed contemporary photographer spent taking photos at Taylor’s Bel Air residence through the coincidental period of Taylor’s death.

Drawn from two Opie photographic series—Closets and Jewels and 700 Nimes Road—where Opie had unlimited access to Taylor’s home, the display is organized by L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art with lead support provided by J.P. Morgan Private Bank; philanthropists Jamie McCourt and Gilena Simons, with UMMA support provided by the U-M Health System; Bank of America; Merrill Lynch; philanthropists Alan Hergott and Curt Shepard, with additional support provided by the U-M Departments of the History of Art; Screen Arts and Cultures; and American Culture.

As we all well know, Elizabeth Taylor had a way of galvanizing attention. And the range of these supporting groups indicates how galvanizing she rightly could be. For Catherine Opie: 700 Nimes Road is as fascinating a keyhole as we could imagine of this world-famous woman’s life.

Opie herself is quite the celebrity. An award-winning photographer (and professor of photography at the University of California at Los Angeles) who works in the intersection of portraiture, landscape, and studio photography, Opie specializes in crafting transgressive imagery that knowingly blurs the intersection of private and public spaces. Mingling her expertise in a variety of photographic and printing technologies with social and political commentary, Opie has consistently produced photographs that document the shadows of our society.

By contrast, these 700 Nimes Road photographs are about as above the photojournalistic fold as Opie’s art gets. Inspired by southern photographer William Egglston’s 1984 photographs of Elvis Presley’s Graceland mansion, she and Taylor shared business manager Derrick Lee, and after negotiating with Taylor’s longtime executive assistant Tim Mendelson, Opie was given full access to 700 Nimes Road. She was busily peering in and around the corners of Taylor’s residence when the actress died of congestive heart failure on March 23, 2011

It’s this dramatic turn of events that makes 700 Nimes Road a masterful display of unceasingly studied and provocative photography. For it’s indeed a perfect melding of professional fine arts photography and screen diva as Opie never actually met Taylor in person through the course of her photographic work.

Thus what’s most fascinating about this non-meeting is the Elizabeth Taylor that Opie illustrates—and not the Elizabeth Taylor she might have met. After all, by the time of this assignment, Taylor had gone through umpteenth career cycles as a screen star ranging from guileless ingénue to international screen icon to television guest star. For Taylor shined bright at each turn of her lengthy career: Winner of two Academy Awards for Butterfield 8 (1960) and Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1966), Taylor closed her acting career with a minor role in 1994’s The Flintstones for which she was nominated as Worst Supporting Actress by the Golden Raspberry Awards.

Yet this was also hardly the extent of Taylor’s lifework. She was an astoundingly successful businesswoman who launched her own best-selling fragrances Passion in 1987 and White Diamonds in 1991 that led to an estimated $600 million to one billion dollar personal wealth. After her death, her estate was dispersed by Christie’s auction house for a then record-breaking $156.8 million dollars with an additional $5.5 million dollars for her clothing and accessories. And her final career turn was an equally winning philanthropist for HIV/AID activism culminating with a Presidential Citizens Medal in 2001.

That’s a lot acclaim for one lifetime. So perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Opie’s art photography is her uncanny condensation of each of these many Elizabeth Taylors with visual references to her many loves—seven husbands; with countless friendships—through the sheer effect of being Elizabeth Taylor.

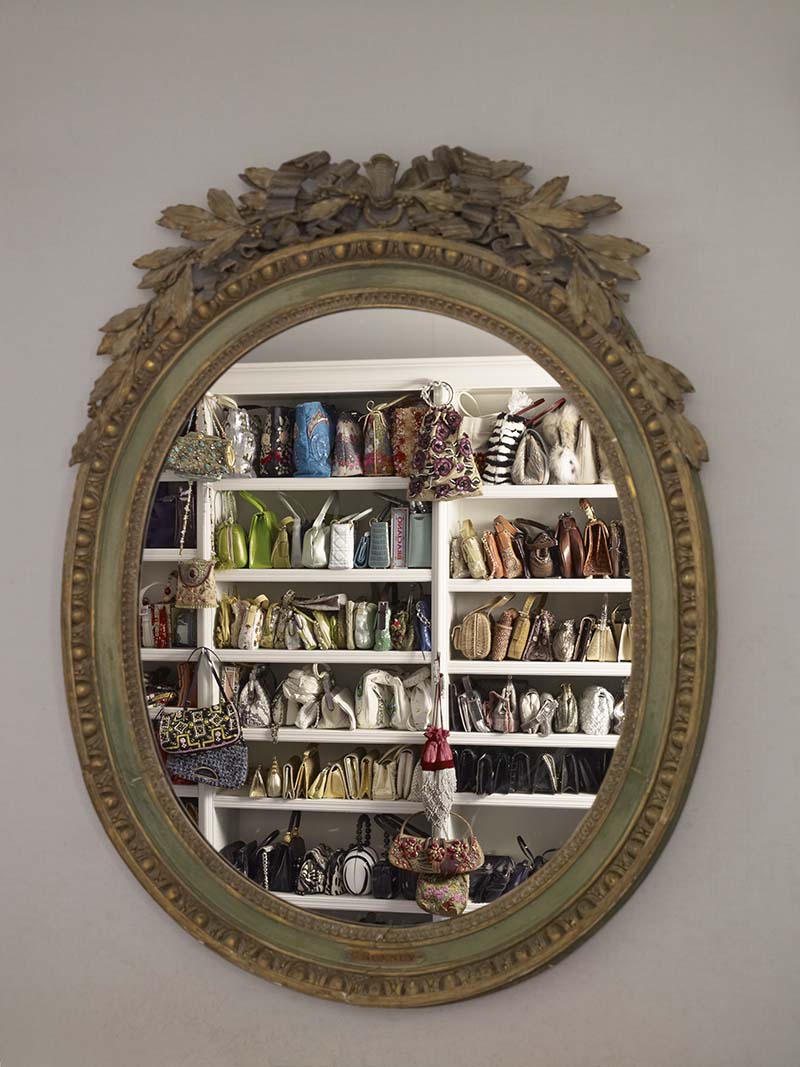

We certainly learn more about what it meant to be Elizabeth Taylor through Opie’s photos than through the proverbial thousand words. In some photos, Taylor’s pets make their appearance rummaging about her personal items. Other photographs feature personal Taylor keepsakes (including one photo of the box holding ex-husband Richard Burton’s 1972 gift of the famed Taj Mahal diamond necklace on her 40th birthday), with other photos featuring her raft of celebrity friends in informal guise. Yet other photographs give us extraordinary visual details of Taylor’s personal routine ranging from a massive number of orderly stashed handbags in one closet to an astounding number of awards in her “trophy room” to a single holiday ornament floating in midair.

Still, fine art will stand out in fine art photography exhibits. And a single signature Opie photograph of Taylor in the abstract as reflected through the visage of her celebrity makes 2010-11’s Elizabeth (Self-Portrait, Artist) archival pigment print a first among equals in this intriguing exhibit.

The bouncing signifiers in this photograph alone make it a superior artwork. For the photo features Opie photographing herself off a bounced image of Andy Warhol’s famed 1966 silkscreen Liz #6 [Early Colored Liz].

In a career unceasingly devoted to celebrity, Warhol’s Liz #6 [Early Colored Liz] is one of his most recognizable portraits. The silkscreen features a desaturated Taylor with a sharp near-monochromatic contrast with the exception of eggshell blue eye shadow and an equally strategic contrast between his framing red background and the actress’ signature brushy bouffant brunette hair. Inferring her beauty as much as painting it, Warhol creates an idealized, romanticized image of Elizabeth Taylor that represents her public image at the height of her glory.

Opie, on the other hand, is the blurred background image to the side of Taylor in Elizabeth (Self-Portrait, Artist). Crafting a superior art photo that bounces herself sideways off the print’s framing glass, Opie links Warhol, herself, and her subject’s idealized portrait in a single image that celebrates Taylor mystique as well as her own personal property autographed by Warhol with the phrase “with much love.”

In a single masterly image, Opie shows us how this actress held—and continues to hold—such strong affect on our emotions to this day. Opie’s Elizabeth (Self-Portrait, Artist) self-reflexively recalls Liz #6 [Early Colored Liz] today with as much love as Taylor was able to engender then.

John Carlos Cantú has written on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

University of Michigan Museum of Art: “Catherine Opie: 700 Nimes Road” will run through September 11, 2016. The UMMA is located at 525 S. State Street. The Museum is open Tuesday-Saturday 11 a.m.–5 p.m.; and Sunday 12–5 p.m. For information, call 734-764.0395.