The Future Is NOW: "Stephanie Dinkins: On Love & Data" at U-M Stamps Gallery

“Binary calculations are inadequate to assess us,” states transmedia artist Stephanie Dinkins, and she approaches AI and technology with this premise in mind.

Her work is a constant unsettling and renegotiation of current technological and social power systems, achieved by asking audiences to consider and create what she calls "NOW." Through her concept of Afro-now-ism, she proposes a collaborative project in which audience members work to dismantle normative, often violent technological structures and build new, inclusive ones.

The Stamps Gallery's Stephanie Dinkins: On Love & Data is the first survey of works by this artist "who creates platforms for dialogue about artificial intelligence as it intersects race, gender, aging, and our future histories.” She makes interactive works that tell us our futures begin now, so we must work to create the world we wish to see.

At the front of the gallery space, a 2021 work titled Afro-now-ism welcomes visitors into the space. A large neon sign reads "AFRO-NOW-ISM," with the words "NOW" and "OWN" illuminated in yellow and intersecting the bright purple and red of "AFRO-NOW-ISM," creating a cross-like design. The gallery wall text illuminates the work:

Theatre Nova's "The Lifespan of a Fact" is a compelling issue play built on a lopsided debate

During a set change in Theatre Nova’s first live, in-person production in front of an audience since March 2020, a stage crew duo flipped and turned an office desk to reveal a fluffy couch.

As this metamorphosis played out on the Yellow Barn’s stage Saturday night, the audience—masked and seated in spread-out chairs—ooooh-ed and gasped in delighted surprise.

I’m clearly not the only one who’s been pining for little hits of theater magic during this pandemic.

Review: Ann Arbor Summer Festival’s “A Thousand Ways (Part One): A Phone Call”

By sheer coincidence, I experienced the Ann Arbor Summer Festival’s theatrical presentation of A Thousand Ways (Part One): A Phone Call at a time when I’d also revisited Mandy Len Catron’s viral essay, “To Fall in Love with Anyone, Do This,” which references 36 questions purported to accelerate intimacy between two strangers.

What’s the connection, you ask?

A Thousand Ways (created by Brooklyn-based troupe 600 Highwaymen) is a phone conversation between you and a stranger, moderated by a pre-recorded, Siri-like voice that poses questions, offers pieces of an imagined narrative, and issues orders. By the end of the hour-long call—filled with seemingly innocuous queries that nonetheless revealed a great deal about ourselves—I felt strangely connected to, and emotionally invested in, the other participant.

To the point that I felt a little heartbroken when I realized that neither of us had enough information to find each other later in real life.

And I felt this sadness despite the fact that we never exchanged names or laid eyes on each other (the latter was part of psychologist Arthur Aron’s experiment, which gave rise to the infamous 36 questions).

The impact struck me as especially curious in this moment, when we’re all slowly emerging from our respective pandemic hidey-holes. We’ve been able to talk by phone with each other this whole time; it was, indeed, one of the safest means of socializing. So why did a pre-recorded moderator make it a far more meaningful, memorable phone conversation than most I had with friends and family during quarantine?

Helicon Haus' "Into the Abyss" explores the bottomless chasm of multidisciplinary art

![]()

Helicon Haus is a student-run organization associated with the History of Art Undergraduate Society at the University of Michigan. The group hosts annual pop-up art exhibits, publishes writings, and creates arts-related world travel opportunities for its members. But for Helicon Haus' annual art exhibition, anyone may enter.

This year’s call took place in April 2021 and resulted in the online exhibition Into the Abyss, which is the second year in which the submissions were presented a virtual format.

For photosensitive viewers, there is a warning: “This website features flashing images.”

The title Into the Abyss is derived from the French term “mise-en-abîme,” which means “placing into the abyss.” Though each finished work suggests its own interpretation of the abyss, the Helicon Haus collective outlines their definition of the abyss in their “Thoughts on the Abyss.” The Abyss refers to nesting heraldic imagery or the “image within the image.” Artists “dove into the abyss of digital space to create their synergistic works. Displayed virtually, these works are placed into the abyss themselves.” The internet and virtual spaces are defined as an abyss within the parameters of the project. Visually, the concept of the abyss is reinforced with the inclusion of the “black hole” portals on the exhibit homepage.

Face to Interface: A2SF’s "Temping" is an uncanny, moving performance for one

I double-checked that I was at the correct address, but the unmarked doors to the office building were locked.

After I tried the handles one more time to see if there was something I had missed, an extremely polite office worker let me in and gave me a welcome packet and some paperwork to sign.

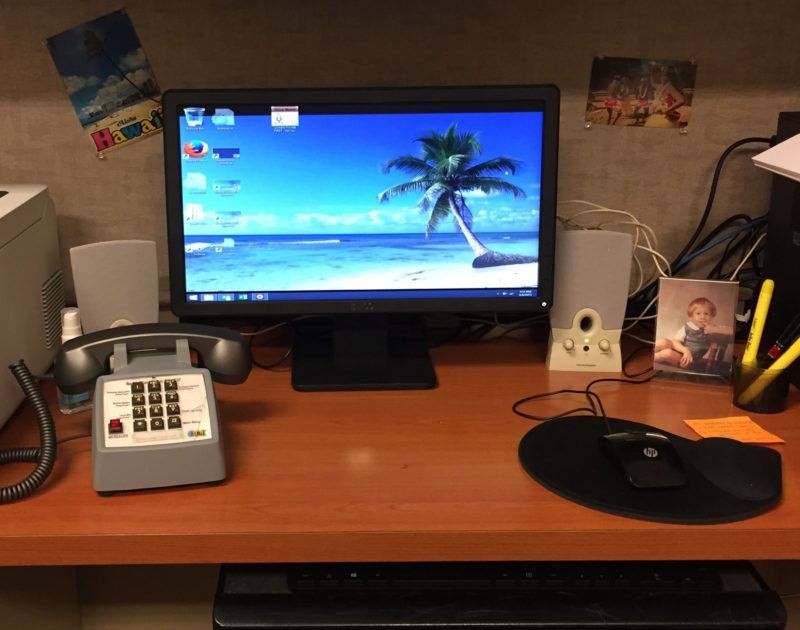

At my appointed time, I was ushered into an isolated cubicle with the usual setup—computer, printer, shredder—but also, family pictures, sticky notes, and office cartoons.

However, I was not here to work but to watch a performance. Or was I the performer?

This is Temping, a show for one that is part of this year's Ann Arbor Summer Festival.

Much like an actual temp job, the show plunks you down into an already-established office eco-system and gives you little training or context for the tasks you are asked to complete. As you receive voicemails, printouts, and emails, you begin to understand your new job: filling in as an actuary for the firm Harold, Adams, McNutt, & Joy. While Sarah Jane Tully is on vacation, it is now your job to mark her clients’ employees deceased or estimate their life expectancy.

Riverside Arts Center’s "Present: An Online Exhibit" offers an egalitarian collection of creative endeavors

Art is essential, whether or not it is created for public display.

All art, whether fine art or craft, is worthy of representation.

Though these two statements seem straightforward, they might be considered controversial in the fine art universe.

Riverside Arts Center’s recent online exhibit, Present, pushes the boundaries of public art in online spaces by eliminating the jurying process and allowing anyone to submit artwork with the expectation that it will be placed in the show. The exhibit's homepage displays a gallery of thumbnail images with brief descriptions of the submissions, which range from regular exhibitors in the Ypsilanti and Ann Arbor area to crafts and Lego projects made among groups of family members. This egalitarian approach offers a fresh perspective on what it means to create art, who this art is for, and what value creativity has when the world no longer resembles the one we know.

Riverside Art Center’s call for submissions asks for work regardless of whether or not the creator is a working artist, and this cosmopolitan approach yielded eclectic results that give viewers a chance to see what creative projects community members have produced during an unprecedented time. The call for art reads:

WSG Gallery's "The World Turns With and Without People" and "Silence and Breezes" explore nature and, sometimes, humans

The artists at WSG Gallery are experts at creating impressive responses to themed prompts. For March's exhibit, Silences and Breezes, WSG artists created selections that range from action paintings influenced by music to calming and atmospheric representations of the natural world. April's theme is The World Turns With and Without People, but like March's show, many of the selected works seem to buzz with anticipation for warm weather.

WSG Gallery continues exhibiting virtually on its website—where past shows can also be seen—and in the 117 Gallery at Ann Arbor Art Center, which is where The World Turns With and Without People will be through May 3.

Theatre Nova’s Zoom play series continues with "Mortal Fools" by Ann Arbor playwright Catherine Zudak

The Goldilocks Principle, though not regularly cited in reference to storytelling, can nonetheless be maddening for those who build narratives.

For how does a writer determine, in each scene, what’s too much information (thus bogging things down and killing suspense) and what’s too little (leaving audiences confused and frustrated)? How do you consistently land upon what feels “just right”?

It’s a notoriously tough needle to thread—particularly within the tight parameters of a 30-minute Zoom play—and this notion was something I thought about often while watching the third and newest entry in Theatre Nova’s Play of the Month series, Mortal Fools, by Ann Arbor-based playwright Catherine Zudak. (The live performance recording of Fools may be viewed—along with the first two entries in Theatre Nova’s Zoom play series, Jacquelyn Priskorn’s Whatcha Doin? and Ron Riekki’s 4 Genres—with the purchase of a $30 series pass, which also covers admission for the fourth and final play in the series, Morgan Breon’s The W.I.T.C.H., scheduled to be performed April 28 at 8 pm)

Yasmine Nasser Diaz's "For Your Eyes Only" invites viewers to wrestle with our public-private lives in the Digital Age

Over the course of the past year, art spaces have shifted from in-person to primarily online, marking an enormous—and sometimes challenging—shift in the experience of an exhibition. Though many galleries and museums have now reopened at least partially, one artist’s recent exhibit bypasses concerns about whether to invite bodies into enclosed spaces. In fact, artist Yasmine Nasser Diaz created a space that's intended to be viewed from outside. Her latest exhibition, For Your Eyes Only, featured in the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery through April 16, questions the boundaries of public and private space through the inaccessible, room-sized installation, which can be viewed from the street outside the gallery.

With the weather warming, now might be a better time to visit the exhibit than when I first attended in mid-February, when I rushed over on opening day. I was eager to participate voyeuristically, as both someone who has avoided public and private spaces during the pandemic, and a fan of installations that mimic a now-foreign “normal life.”

UMS's stage-film hybrid production of "Some Old Black Man" explores race and generational conflict

This review originally ran on January 19, 2021. We're featuring it again because UMS is streaming "Some Old Black Man" for free March 1-12, 2021, but you have to register for the screening here.

The closer we are to someone, the more likely we are to engage in picayune arguments that quietly scratch at, and chafe against, far deeper issues.

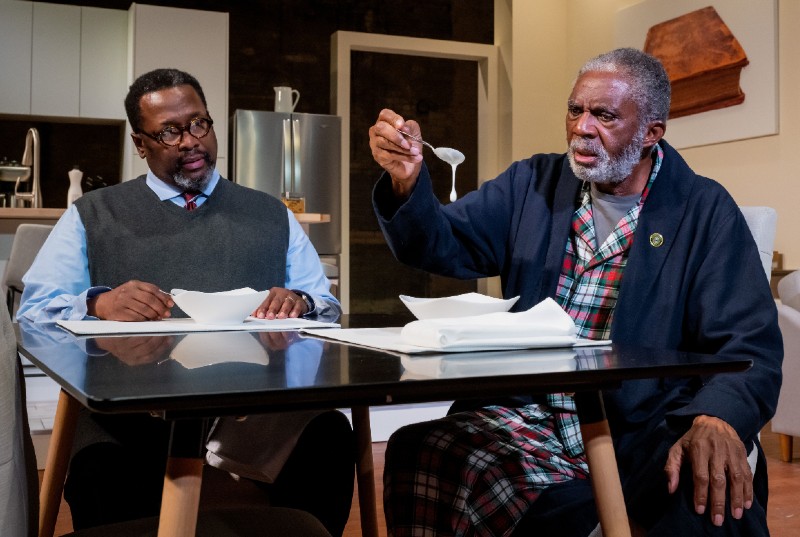

Which is to say, a family clash about what to eat for breakfast—a conflict that kicks off early in the recently streamed University Musical Society theater production of James Anthony Tyler’s two-hander Some Old Black Man—is often about something else entirely.

In the case of NYU literature professor Calvin Jones (Wendell Pierce) and his ailing, 82-year-old father, Donald (Charlie Robinson)—who’s just been relocated from his home in small-town Mississippi to Calvin’s posh Harlem penthouse—a conflict about a yogurt parfait strikes notes of really being about control, and conflicting generational perspectives, and blackness, and ego, and masculinity.

That is an awful lot for a soupy bowl of granola and fruit to carry.

But Tyler understands that to mine down to the heavy, hard-to-face stuff, humans inevitably have to start the process by hacking away at nonsense for a while—with absurdly tiny pickaxes.