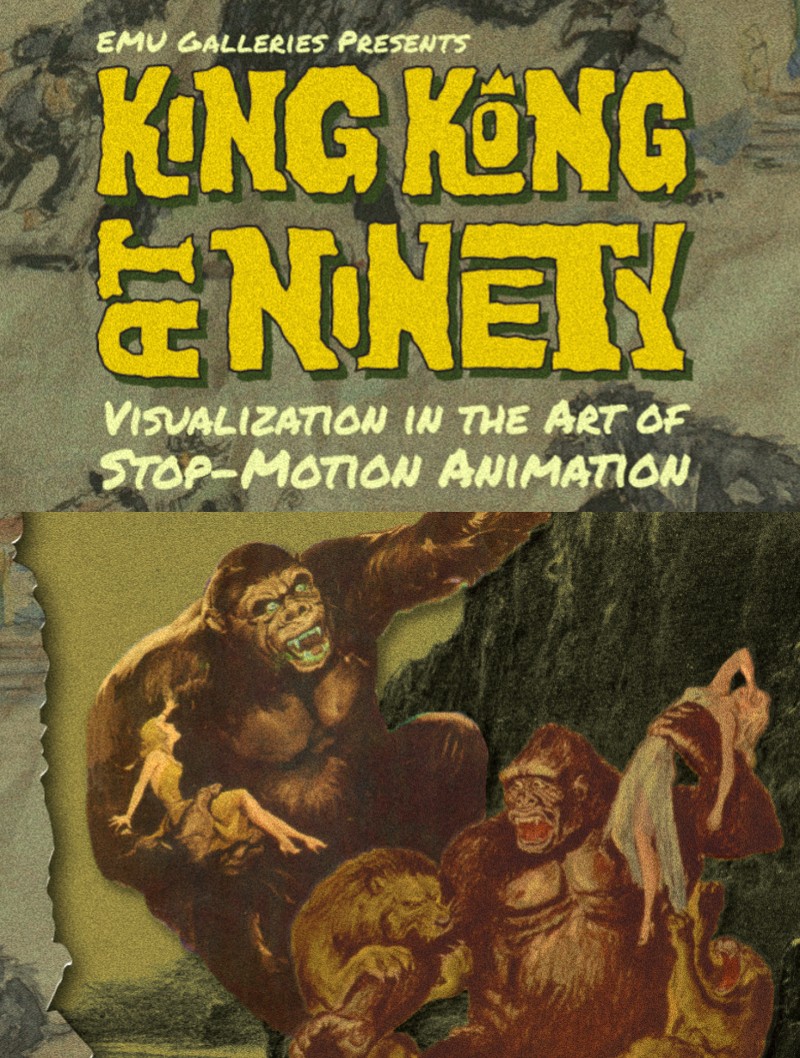

EMU's "King Kong at Ninety: Visualization in the Art of Stop-Motion Animation" celebrates the creativity behind the film that helped launch the Creature Feature

While spending an hour-plus perusing Eastern Michigan University’s exhibit King Kong at Ninety: Visualization in the Art of Stop-Motion Animation, I was struck by how, in some ways, it’s probably harder for young film buffs to stumble upon the old classics.

Admittedly, nearly all movies that survived are available to us at any moment now, but that tsunami of choices also means viewers must specifically seek out a film like King Kong (1933) instead of merely tumbling out of bed before your parents get up on a Sunday morning, turning on the TV, and sampling that week’s “Creature Feature”—a genre largely spawned by the runaway blockbuster success of King Kong.

Even so, as demonstrated by King Kong at Ninety—on display at EMU's University Gallery through February 23—theatrical rereleases of the film served this same purpose for years, offering moviegoers multiple opportunities to experience what were, at the time, cutting edge, eye-popping visual effects. (It’s interesting to note how the poster art changed with each release, as well as how it was visually marketed in other countries.)

Plus, EMU’s exhibit offers up Depression-era magazine features dedicated to revealing how these cinematic images were achieved—though more of these articles trafficked in shoddy guesswork (i.e., an actor in a gorilla suit) than in accurate, researched reporting.

But even these misinformed attempts hint at the widespread sense of wonder and curiosity inspired by King Kong. So how did this seminal movie come to be made?

The Ark’s Ann Arbor Folk Festival Makes Welcome Return to U-M’s Hill Auditorium

After three years away, it felt heartwarming to attend the 46th annual Ann Arbor Folk Festival on January 28.

As a regular past attendee, there was something special about going in-person again to celebrate The Ark’s largest concert and fundraiser of the year.

For once, the entire show occurred before a live audience without any COVID-19 cancellations (aka 2022) or virtual alternatives (aka 2021). (January 27’s sold-out Friday Night Folk: BanjoFest also featured in-person performances with Valerie June, Thao, Yasmin Williams, and Michigan’s Rachael Davis at The Ark’s Ford Listening Room.)

A renewed sense of gratitude filled the air as a lineup of emerging and established folk acts—including Ani DiFranco, St. Paul & The Broken Bones, and Patty Griffin—took the stage at the University of Michigan’s Hill Auditorium for five hours of folk-inspired and folk-adjacent music.

Alongside co-emcees SistaStrings, singer-songwriter Peter Mulvey uttered the words everyone had waited to hear since 2020: “Omigod, we’re finally back!”

Open the Vaults: Tania El Khoury's multimedia installation “Cultural Exchange Rate” immerses you in the artist's family history

If you could unearth all the secrets of your family’s past, would you?

Lebanese artist Tania El Khoury set out to do that with her interactive art installation Cultural Exchange Rate, which is presented at the Stamps Gallery, courtesy of UMS, until January 29. The multimedia work tells the artist's mission to trace her family’s roots by having gallery-goers open locked boxes and stick their heads inside to see videos, sounds, objects, and images of El Khoury's family journies between continents.

Originally from Akkar, a small village in Lebanon located near the river that separates Lebanon and Syria, El Khoury’s great-grandparents migrated to Mexico during a civil war. Her grandfather was born in Mexico, but her family eventually moved back to Lebanon, where he collected old coins and Lebanese liras, hoping they would be worth more than their original value one day when the currency exchange rate changed.

The story progresses to the present, with the artist becoming pregnant. In hopes of giving her unborn daughter citizenship in a country with a better passport and more cultural freedom, El Khoury searches for her grandfather’s birth certificate in Mexico, so her daughter can gain Mexican citizenship. The journey is frustrating, and while she hits a lot of dead ends, she also discovers family members in Mexico City that she didn’t know she had. Her story is one of blended cultures, resilience, survival, and hope.

"Are we not drawn onward to new erA" Encourages Understanding the Climate Crisis From an Unconventional Perspective

A few people quietly left the UMS presentation of Are we not drawn onward to new erA mid-performance while many others stayed and took part in a spirited standing ovation.

Conceived and performed by Belgian theater collective Ontroerend Goed, it’s just one of those shows: an experimental, challenging piece of theatrical performance art that you either embrace or reject.

And your reaction likely depended on your capacity for patience and ambiguity, which was initially tested when deciding whether or not to purchase a ticket for the January 20 or January 21 performance.

By way of a vague show description, the UMS site reads, “You can’t put toothpaste back in the tube. You can’t remake a shattered vase. Or undo the damage that humans have inflicted on the Earth. But what if you could—in just one night?” (When asking my husband if he wanted to accompany me to the show, he asked, “What is it about?” “Uh … repair, I guess?” He didn’t come.)

“The Plastic Bag Store” Uses Art to Raise Awareness About The Pervasive Problem of Plastic Packaging

It’s an unnervingly perfect coincidence that when you emerge from the installation/play The Plastic Bag Store (TPBS) presented by University Musical Society (as part of its No Safety Net series), you see a cafeteria space with boxes of individually packaged snacks for sale on a rack.

Why? Because if there’s one thing TPBS achieves, it’s a newly heightened, re-calibrated sensitivity to the layers of packaging that surround us so constantly that we don’t even register them anymore.

In the show’s program – which is, fittingly, only available via a QR code – creator Robin Frohardt explains that the show was born in 2015, “after watching someone bag and double bag all my groceries that were already bags inside of bags inside of boxes. I wanted to highlight the absurd amount of packaging we are using and throwing away by making something even more absurd: a grocery store that only sold packaging.”

But the packaging in TPBS are fashioned to resemble typical grocery store fare: produce, seafood, bakery desserts, flowers, and salads, as well as boxes of familiar-with-a-twist items like Caps N’ Such cereal, Straws (instead of Stroh’s) ice cream, Bitz of Plastic Crap.

Selina Thompson's “salt: dispersed” is a powerful document of her monologue retracing the transatlantic slave route forced on her ancestors

In 2016, Selina Thompson, an interdisciplinary artist based in Birmingham, England, went on a journey to retrace the path of her ancestors. That path was that of the transatlantic slave trade.

The writer and performer recounts her trip in salt, a monologue she first performed in 2017, and now in salt: dispersed, the film adaptation of her stage presentation. UMS is streaming the film for free through February 13 as part of its Renegade Festival's No Safety Net series, which focuses on theater and art installations.

Thompson's mission started in the U.K., boarding a cargo ship with another Black female artist, and discovering a story so powerful it takes the air out of your lungs.

Fraught reunions with old friends are at the core of Penny Seat's "First Snow"

The prospect of seeing friends from high school, after a years-long separation, always feels fraught. Will it be awkward? Will they judge you? Will you judge them? What will you talk about? Will you somehow ruin perfectly contained, long-packed-away memories?

This anxiety’s at the core of Joseph Zettelmaier’s new play, First Snow, now having its world premiere production via The Penny Seats Theatre Company at The Stone Chalet Event Center in Ann Arbor.

Evan (Michael Alan Herman), a Chicago-based photographer, vanished from his small hometown shortly after his high school graduation, when both of his parents died in a car accident. In the 10-year interim, he’s eschewed all contact with his best high school band buddies Lisa (Josie Eli Herman) and Bob (Jonathan Jones).

But music teacher Lisa—with whom Evan was once romantically involved—finally tracks him down to invite him to a holiday party in her home, which she shares with her young daughter, Natalie (Patrice Linman); and because Evan is working on a photo series about holiday celebrations, the invitation dovetails with his work. What Evan doesn’t know, though, is that he and Bob—and Bob’s wide-eyed, former-popular-girl wife Nora (Celah Convis)—are the only ones on this party’s guest list.

Not that this is malevolently ominous. The three friends simply have things they need to say to each other in order to move forward.

Encore Theatre's “A Christmas Story: The Musical" sings the praises of the classic film

A stage musical based on a beloved film classic—like, say, A Christmas Story: The Musical, now being staged at Dexter’s Encore Theatre—can be a double-edged sword.

Yes, it’s a known commodity, so people will often line up to see it without too much coaxing, but the show’s creators must delicately thread the needle of staying true enough to the original material to satisfy fans, while also providing enough surprises and new elements to remake the story in a new medium.

If anything, the musical adaptation of A Christmas Story—with a book by Joseph Robinette, and music and lyrics by University of Michigan alums Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (before they won Tonys for Dear Evan Hansen)—errs slightly on the side of dogged loyalty to the 1983 movie’s script, straining to check every classic-moment box.

Yet the reason Story has so many such boxes is because it is a funny, charmingly rendered, nostalgic slice of American childhood, set in a small Indiana town in 1940.

Drawn from radio stories told by humorist Jean Shepherd in the 1950s, Story focuses on the pre-Christmas trials and tribulations of 9-year-old Ralphie Parker (Gavin Cooney), who desperately wants a Red Ryder BB gun. The problem is, he can’t convince his parents (David Moan and Jessica Grové), his teacher (Alley Ellis), or even a department store Santa (Mitchell Hardy) that if he gets one, he won’t “shoot his eye out.”

But Ralphie keeps scheming while also dealing with bullies, theme papers, and a gruff father who’s chasing his own form of validation.

First, let’s address the baby elephant in the room:

Andrea Carlson's "Future Cache" exhibit at UMMA imagines decolonized landscapes for the native peoples violently removed from their land

“Gidayaa Anishinaabewakiing / You are on Anishinaabe land”

The title of Andrea Carlson’s multidimensional installation Future Cache at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) references the Anishinaabe storage practice of using underground caches to store supplies through the seasons.

The centerpiece of Future Cache, however, doesn't train your gaze toward the ground but up to the sky.

UMMA's Vertical Gallery has a towering 40-foot-high wall of memorial text. Written by the Burt Lake Tribal Council and presented in Anishinaabemowin (translated by Margaret Noodin and Michael Zimmerman Jr.) and English, the words commemorate the historical and ongoing effects of colonial violence on the Cheboiganing (Burt Lake) Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians.

On the lower level, a cache of Carlson's paintings complements the tower of text with imagined decolonized landscapes, as well as two carefully selected artifacts. Curator Jennifer M. Friess writes in the gallery text that Carlson aims "to draw attention to the theft of Indigenous land and to express solidarity with Indigenous communities on the long journey toward restitution.”

"Conversations on Mortality" at 22 North looks to transcend the silence about the dying side of living

Conversations on mortality are difficult, often avoided, and in America, they are traditionally taboo. The 22 North gallery in Ypsilanti welcomes the thought-provoking exhibit Conversations on Mortality, which confronts our impermanence, the inevitability of death.

The exhibition's multimedia works engage with loss, mourning, and what is left behind once someone is gone. Described by the curators as “a chance to transcend the silence,” Conversations on Mortality offers works driven by the lives of the artists. Not only do they address the complexity of their mortality and loss of loved ones, but also their experiences of living with disability, illness, and the impact of COVID-19.

Entering the space, hanging lanterns in an autumnal palette cheerily frame serendipitously matching works by curators Sharlene Welton and Tim Tonachella. I had a chance to speak with Welton who is both the show’s curator and an artist when I visited 22 North. Welton said she created the lanterns as part of an interactive element to the opening night, where visitors were able to decorate and write their names on the lanterns before hanging them. The pieces by Welton (a large painting) and Tonachella (two photographs of cemetery views) were brought in last minute when an artist was unable to make the show, but adding the works ended up being a great aesthetic success.

Welton and Tonachella’s gallery statement notes the overlapping threads among the works, as artists grapple with the questions, “How do we embrace the changes that come from death and dying, and more importantly, how we assimilate the loss into our daily living?” Though these may, ultimately, be unanswerable questions, they are worth asking—especially when operating within a mainstream American culture that predominantly ignores them.