TAKESHI TAKAHARA: IN LOVE WITH THE PROCESS

KA Letts (of RustbeltArts.com) has written a great review of the WSG Gallery's current exhibition.

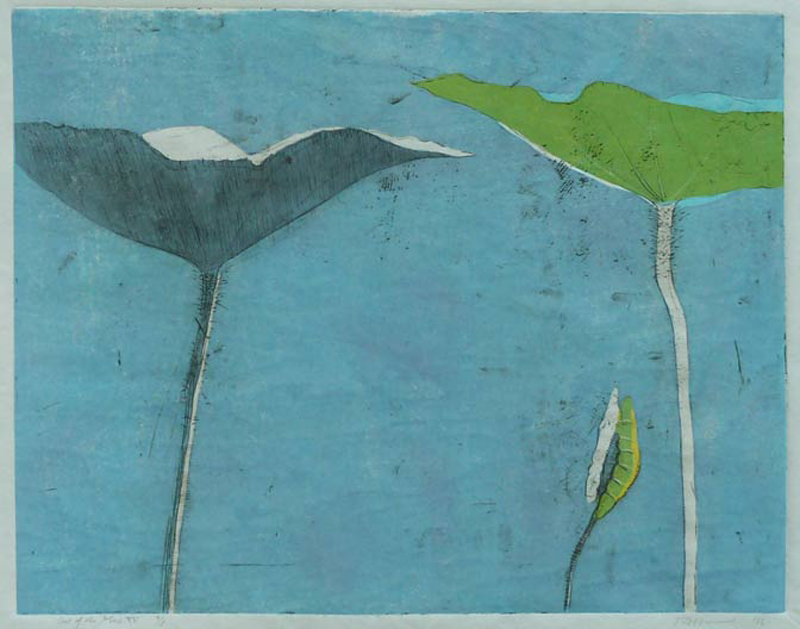

"Takeshi Takahara believes in the handmade, the one-of-a-kind, the idiosyncratic. This might seem a counterintuitive attitude in an accomplished master of intaglio printmaking, a medium which embodies the aesthetic of the multiple and reproducible. But in his first solo show at WSG Gallery he demonstrates that his unique, eco-friendly hybrid intaglio/woodcut process for creating small print editions (often only 5 to 9 per title) can deliver artworks that pack all the punch of a one-of-a-kind painting. Imperfection, a meticulously curated and well arranged grouping of prints on the theme of the lotus, is on view in the WSG gallery from now until October 22."

Visit RustbeltArts.com to read the review in its entirety.

K.A. Letts is an artist and art blogger. She has shown her work regionally and nationally and in 2015 won the Toledo Federation of Art Societies Purchase Award while participating in the TAAE95 Exhibit at the Toledo Museum of Art. You can find more of her work at RustbeltArts.com.

Imperfection will run at the WSG Gallery, 306 S. Main Street, through October 22, 2016. The WSG Gallery is open Tuesday-Thursday, noon–6 pm; Friday-Saturday, noon-9 pm; and Sunday 12-5 pm. For information, call 734-761-2287.

Review: Re: Formation at the Ann Arbor Art Center

The Ann Arbor Art Center’s latest exhibit is the Re: Formation to help begin all reformations.

As the exhibit’s statement tells us, the display “examines this unique moment [in history] when ordinary people are declaring a la Peter Finch [from Sidney Lumet’s 1977 film Network]: “‘I’m mad as hell and I won’t take it anymore.’”

This is indeed the precise sentiment of this unceasingly clever exhibit of art.

For Re: Formation, the latest offering of Rocco DePietro and Gloria Pritschet, founders and directors of the Gallery Project, follows suit with this artful duo’s willingness to go where most other forums fear to tread. Ann Arbor's Art Center exhibit pairs with an earlier August incarnation of the show exhibited through the auspices of Toledo, OH’s Art Commission.

As the exhibit statement continues, “What is different at this time is that people who have been silent, or silenced, are standing up, speaking out, and mobilizing for needed change. Highly divergent in life styles with broad-ranging backgrounds, beliefs, and values, these individuals are expressing justifiable anger at the accumulation of horrific events and unrelenting injustices that characterize our current era.

“They are teaming up across race, gender, politics, and social status with empathy and compassion for their fellow human beings. Their actions are reestablishing belief in a positive future based on fairness, equity, and genuine possibility for all.

“Is this a tipping point, a moment for reform, or even a revolution? Or is it just another blip before capitulation and regression?”

These are, of course, highly potent questions. The very nature of this articulation will be considered by some as transgressive. But the paradox, of course, is that the very nature of the contention leaves motivation and avocation hanging equally in the balance.

Because of course, the definition of art itself is being challenged in Re: Formation. What is the purpose of art? Is it meant to merely have a decorative function? Or is it meant to provoke and challenge one’s preconceptions?

The Gallery Project is letting us know what they think, and towards this end DePietro and Pritschet have mobilized a formidable array of national, regional, and local talent whose outlooks cut across a whole host of social, political, and cultural viewpoints. There are (to borrow from a questionable cliché) no sacred cows here. And even if there were, it would be just as many of the artists on display who would want to devour it as there are others who would hold it sacred.

Local talents on display are Ann Arbor’s Heather Accurso, Morgan Barrie, Carolyn Barritt, Ruth Crowe , K.A. Letts, Melanie Manos, Michael Nagara, Sharon Que, Jesse Richard, Meagan Shein, Ellen Wilt and Richard Wilt. Dexter is represented by Tohru Kanayama; with participation by Ypsilanti’s Nick Azzaro and Jessica Tenbusch.

Among the works on display, Azzaro gives us a potent taste of Re: Formation’s disposition. His unframed “Progress at the Ol’ Smith Furniture Building” color photograph touches on all the ideas stated in the exhibition’s gallery statement.

There are, of course, Americans who to this day think of the Confederate States of America’s second Battle Flag as a sacred totem of historic significance with as much a symbolic value as the United States’ stars and stripes. Indeed, these stars and bars—in either its peace or war confederate configuration—are still part of the symbol (and considered a venerated heritage) in parts of the American south and officially designated in three southern states.

But the flag is also a highly potent symbol of a heritage that is itself emblematic of one of the most controversial aspects of our republic’s heritage. Representative of the defense of slavery as a political institution, the Dixie Battle Flag serves as a visceral reminder of attitudes that cut across economic, social, and cultural lines. As such it’s not uncommon to find the flag on private property such as flag pole or car—now often in a setting that is seemingly as much defiance as it is supportive.

Thus Azzaro’s photograph transgresses these values by vividly appropriating the symbol and subverting its erstwhile significance. Running across a dilapidated storefront with this flag in flames, “Progress at the Ol’ Smith Furniture Building” is a straightforward, aggressive recasting of social, economic, political, and cultural American expectations.

Just like many other artworks on display in this highly emotionally charged exhibit, if Azzaro’s “Progress at the Ol’ Smith Furniture Building” isn’t a Re: Formation of American expectations, it’s hard to imagine what might be.

John Carlos Cantú has written on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

Re:Formation will run through October 8, 2016, at the Ann Arbor Art Center, 117 W. Liberty St. Exhibit hours are 10 am to 7 pm, Monday-Friday; 10 am to 6 pm, Saturday; and noon to 5 pm, Sunday. For information, call (734) 994-8004.

Fabulous Fiction Firsts #613

Following in her illustrious parents' footsteps, Irene is a professional spy for a shadowy organization called the The (Invisible) Library * * that collects important works of fiction from all of the different realities. After wrapping up a most difficult case, she finds herself immediately assigned a new mission - to retrieve a particularly dangerous book in an alternative London while shackled with a new trainee, Kai.

When they arrive, they find the city populated with vampires, werewolves, and Fair Folk, and the book they are after, has already been stolen. Soon they realize several parties are prepared to fight to the death for the tome, one of them a handsome detective named Peregrine Vale. It also becomes clear fo Irene that Kai is hiding secrets, secrets that could prove as deadly as the chaos-filled world they find themselves in.

"Bibliophiles will go wild for this engaging debut, as Genevieve Cogman hits all the high notes for enjoyable fantasy. Intriguing characters and fast-paced action are wrapped up in a spellbinding, well-built world." (Library Journal)

"Reminiscent of the works of Diana Wynne Jones and Neil Gaiman, Cogman's novel is a true treat to read." (Publishers Weekly)

I hope you are a fast reader. A much anticipated sequel The Masked City is on its way, and not a minute too soon.

* * = starred reviews

Review: Liberty's Secret: The 100% All-American Musical

"This is like the bar mitzvah I never had," U-M art and music professor Andy Kirshner joked while standing on the Michigan Theater's stage on Thursday evening, hosting the premiere screening of his locally made, original feature film musical, Liberty's Secret.

Indeed, the quip aptly described the event's affectionate, enthusiastic, communal atmosphere. (Kirshner's last words at the mic were, "Could my wife please raise her hand, so I can find my seat?") Approximately a thousand people turned out to see Kirshner's film about an unlikely romance that blooms between a jaded, Jewish Presidential campaign communications manager (Nikki, played by Chelsea native and U-M grad Cara AnnMarie) and a sheltered, small-town pastor's daughter (Liberty, played by Oakland University grad Jaclene Wilk) whose angelic singing voice makes her not just America's viral sweetheart, but the picture of "family values" wholesomeness that Nikki's moderate Republican candidate, Kenny Weston (Williamston Theatre co-founder John Lepard), needs to win.

Clearly, Thursday night's crowd enjoyed playing "spot the local artist": There's U-M professor and theater artist Malcolm Tulip, leading a "gender re-orientation camp" number in the Michigan Union ballroom! There's former Performance Network artistic director and actor David Wolber, playing a security guard that puts the stop on Purple Rose Theatre artist Tom Whalen! There's local actor Rusty Mewha, playing Weston's cynical campaign manager! And in what might have been the most well-received featured appearance, Kirshner himself, wearing a bushy wig, played Rolf Schnitzel (?!), host of the cable news program, The Briefing Room.

Local filming locations included Ann Arbor's Millenium Club, the Vineyard Church, a former restaurant in Ypsilanti, a wedding chapel in Milan and more.

Getting the tone right for satire is often tricky, and Kirshner stumbles occasionally, making Liberty's well-intentioned father and his congregation too cartoonish at times, and painting Weston in broad, George W. Bush-style strokes. He wisely checks this impulse now and then, most notably when Liberty calls out Nikki for looking down her nose at everyone who believes in God. And there are some pretty fun touches, too, like when Weston's debate prep takes place in front of a white board that has mixed-up messages like "It's the stupid economy," and when Liberty's definition of love as self-sacrifice prompts Nikki to reply, "No, that's co-dependency."

Kirshner's original score, while varied and sophisticated, only sometimes sounds like it belongs in the world of musical theater. The most successful number by far is a tap duet between Liberty and Nikki called "Stay on Message," which not only spotlights Debbie Williams' fun choreography, but dissects the doublespeak of political rhetoric, as Nikki instructs Liberty on how to translate terms for the media ("Don't say 'intervention,' say 'keeping peace,'" etc.). In addition, the song goes some distance toward partially filling a larger gap in the narrative, which is: what makes these two very different women fall in love with each other? We're told that they do, but there's little meat on the bones of this particular (and crucial) development.

But these artistic quibbles don't detract from the fabulously fun party that hundreds of locals, students and community members both, attended to collectively celebrate a project that brought them together. The film's two female leads do fine work, and Lepard seems to have the time of his life playing a bumbling politician. Mewha's reaction shots alone earn big laughs, and Alfrelynn J. Roberts, Nikki's colleague and friend, gracefully grounds the story by way of sharing her own past with Liberty's father.

So Liberty's Secret may be destined to be more of a local hit than a national one, but in many ways, it's Kirshner's funny, sweet valentine to the community he calls home; and because of how recently the Supreme Count ruled in favor of same-sex marriage, watching a wedding with two brides - who serenade each other, no less - can be quite moving.

(Liberty's Secret is available for pre-order at http://libertysecret.com, with delivery expected in early November. Shortly thereafter, it will be available on iTunes, Amazon Prime, and other formats.)

Jenn McKee is a former staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News, where she primarily covered theater and film events, and also wrote general features and occasional articles on books and music.

Fabulous Fiction Firsts #612

A Hundred Thousand Worlds * by Bob Proehl is a mother-son cross-country road trip through the world of comic-cons,

New York actress Valerie Torrey, who has a successful run playing Bethany Fraser in a syndicated X-Files-ish TV show called Anomaly is taking her 9 year-old son Alex on a road trip to LA where his father Andrew lives.

Along the way, Val agrees to make appearances at comic book conventions. From Pittsburgh to Cleveland, from Chicago to Las Vegas they are increasingly being drawn into the lives and drama of the other regulars - artists, writers, agents, publishers and a strange world of "cosplay" (costume play), mostly young women who dress up as comic book characters.

For Alex, this world is a magical place where fiction becomes reality, but as they get closer to their destination, he begins to realize that the story his mother is telling him about their journey might have a very different ending than he imagined.

Debut novelist "Proehl has done an excellent job of integrating all of the story lines and creating memorable characters to populate them. Though not without its melancholy moments, the story is deeply satisfying and will delight both comics fans and general readers." (Booklist)

* = starred review

Fabulous Fiction Firsts #611: Spotlight on Psychological Thrillers

An August pick on Indie Next and LibraryReads lists, and a runaway UK debut bestseller, Behind Closed Doors * by B.A. Paris is one of the most terrifying psychological thriller you are likely to come across.

London attorney Jack Angel - movie-star-handsome and successful, sweeps Grace Harrington off her feet when he offers to dance with Millie, Grace's Down-syndrome younger sister under her care. The first sign that things are not what they seem to be is when Millie tumbles down a flight of stairs on their wedding day. On their honeymoon, Jack made clear his psychopathic plans, using Millie as leverage to ensure Grace's cooperation.

"Debut-novelist Paris adroitly toggles between the recent past and the present in building the suspense of Grace’s increasingly unbearable situation, as time becomes critical and her possible solutions narrow. This is one readers won’t be able to put down." (Booklist)

All the Missing Girls * , the first adult title by YA author Megan Miranda, is about the disappearances of two young women a decade apart. It has been 10 years since Nic(olette) Farrell left Cooley Ridge after her best friend, Corinne Prescott, disappeared without a trace. Now a cryptic note from her dementia-ravaged father brings her home. Within days of her arrival, her young neighbor Annaleise Carter disappears, reawakening the decade-old investigation that focused on Nic, her brother Daniel, boyfriend Tyler, and Corinne's boyfriend Jackson.

Told backwards from Day 15 to Day 1 since Annaleise's disappearance, Nic works to unravel the shocking truth about her friends, her family, and ultimately, herself. "Miranda convincingly conjures a haunted setting that serves as a character in its own right, but what really makes this roller-coaster so memorable is her inspired use of reverse chronology, so that each chapter steps further back in time, dramatically shifting the reader’s perspective." (Publishers Weekly)

The Trap by East German debut novelist Melanie Raabe is a fast, twisty read.

Reclusive novelist Linda Conrads hasn't left her home since she discovered her sister's body 11 years earlier. When she sees the face of the murderer on television, the same face that she saw leaving the crime scene, she goes about setting a trap by crafting her next thriller utilizing all the details of her sister's murder. But her careful plan goes horribly awry.

Film rights sold to TriStar Pictures.

* = starred review

Review: Falling Up and Getting Down, UMS Season-Opening Live Skateboarding + Music Celebration

The professional skateboarders at Falling Up and Getting Down, University Musical Society’s (UMS) season-opening event on Sunday, September 11, at Ann Arbor Skatepark, riveting as they were, were just part of the event's attraction. Jazz trio Jason Moran and the Bandwagon, joined by saxophonist Ingrid Laubrock, were improvising on a stage behind the bowl. Instruments were in conversation with each other, and the conversation included the skaters too.

The skaters’ own improvisations didn’t respond to individual musical statements, at least not that I could perceive; rather, the feel of the music infused all the skating with its particular energy. The edge of the stage proved a highly permeable boundary between music and skateboards; skater Chuck Treece joined the Bandwagon on guitar and skater Ron Allen took the mike to layer rhyme over the music. Early on, Tom Remillard launched himself up and over the lip of the pool to briefly plant a foot on the edge of the stage before hurling himself back down the steep face of the pool like a wheeled stage diver, a maneuver that other skaters riffed on later.

The skaters were the main attraction for me. Having surfed but never been on a skateboard, I imagined their ride to be like catching one constant wave. What a rush it must be, plunging down into the trough of the concrete “bowl” and then decelerating as they ride up its concave side. Sometimes they immediately cut down again, sometimes they skated along the crest, sometimes they hit a divine moment of suspension at the top—airborne, or upside-down balanced on one hand, the other hand fixing the board to the soles of their feet. There was wow-inducing virtuosity (and good-natured rebounds out of the failed attempts at that virtuosity), but what I found most hypnotic was the fact of the ride: that ongoing forward propulsion, and the pendulum energy of their recurring drops into and ascents out of the bowl.

Hot skateboarders and hot music together: that’s a lot going on. But there was still more, something about the people assembled in the park. “Community” comes to mind, but I rush to justify that worn-out word and provide examples of what I have in mind. My twelve-year-old daughter attended a girls-only skateboard session in the morning and got personal instruction from 17-year-old pro Jordyn Barratt. At the event, Barratt mugged for a photographer as she rode her board in an arc over the head of Ken Fischer, UMS President, who was seated at the bottom of the bowl. My daughter was star-struck (over Barratt, not Fischer!), telling me how cool Jordyn is and, I think, hoping to catch her eye. Meanwhile, local skaters weaved among the pros.

There was a sociable, we’re-all-here-together vibe, and that must be at least partially attributed to UMS’s desire to “give back to the community” with this event. “Community” often means connecting with audiences outside the older, wealthier population usually associated with concert halls, and if that’s the definition in operation here, certain elements of Falling Up and Getting Down were particularly effective. It was free and in a public park. The “free” part is not to be underestimated, especially given the often-prohibitive price tag on concerts in theaters. The “public park” part is also powerful; this was not just any public park with lawns and swing-sets, but a skatepark with cement hills and paths and loops.

There were also a fair number of teenagers, and tattoos, punk rock t-shirts, Chuck Taylor sneakers, and dreadlocks, alongside people with grey hair, tailored clothing, and sensible shoes. I acknowledge how odious generalizations based on appearances are, but admit that I surmised that this older set came for the jazz more than the skateboarding. The fact remains, though, that there were assembled people who looked really different from one another, and their difference was made more striking by the fact that they were side by side at the skatepark. We were all listening to the Bandwagon, and regardless of who considers themselves jazz connoisseurs or knows Jason Moran’s reputation, the sounds they conjured were bewitching. We were all watching the skateboarders fly, and regardless of whether you’ve ever heard of Tom Remillard, it was inspiring and gladdening.

My husband, impressed with the scene, commented how cool it is that our town has a skatepark, that when he was a teenager, skateboarding was on par with doing drugs, wearing black leather jackets, and generally getting in trouble. Skateboarding was not just teenagers, it was bad teenagers; any business with a promisingly inclined stretch of sidewalk posted a prominent “no skateboards” sign. Some of that has obviously changed, either with the time or the place; witness the number of people of all ages on skateboards and the family-friendly vibe at Ann Arbor Skatepark. However, skateboarding still has a reputation and often a feel of angry rebellion and intimidating cool; pro-skateboarder Andy Macdonald’s clean-cut image is an exception that the press makes much of, and I feel instantly old, dowdy, lame, and conservative when I encounter skateboarders on the street.

And the skateboarders didn’t seem off-puttingly cool; they offered one another encouraging high-fives and praise, and shared the limelight with respectful turn-taking. If the situation were reversed, I hope that the clothing and attitudes of the concert hall that might be intimidating to outsiders would be similarly mitigated by friendly and polite interaction.

Anyway, it was a situation in which people of apparent difference found common ground—a true and apt definition of community, compelling me to remove the cynical quotation marks from around that word. While the unusual combination of jazz improvisation and skateboarding—both of the highest quality—was the attraction that drew these people, I think the secret ingredient that enabled this particular instance of community was the setting: the shared public space. And so, I’m impressed with my new home, not just for bringing Jason Moran and Andy Macdonald here, but for bringing them together and for making this happen free of charge in a public venue.

From 1993-2004, Veronica Dittman Stanich danced in New York and co-produced The Industrial Valley Celebrity Hour in Brooklyn. Now, PhD in hand, she writes about dance and other important matters.

Review: "Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light," University of Michigan Museum of Art

The University of Michigan Museum of Art’s Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light is easily going to be one of the most accurate art exhibition titles of 2016. This tidy 23-piece UMMA display shows the world-famed Bravo at his best: For he’s indeed a master of photographic light—as well as a poetic artist.

All photographers are capable of what is sometimes called a “privileged moment.” After all, it would seem simple enough to capture a moment with photography: You just point your camera and click.That's what's been happening photographically for quite nearly this last 150 years ... right?

Well, not quite. After all, you have to know what you're looking for because the most remarkable thing about photography is the camera’s utterly elastic way of recording an image. The world isn't as transparent as might seem apparent on first observation. And it doesn’t take much more than one’s last batch of photos for the confirmation.

Bravo, on the other hand, knew what he wanted to see—but the craft didn’t stop there. For the next rule consists of mechanistically knowing how to get what you want to see. And this is as complicated a task as knowing what one’s looking for.

It’s at this point that poetry arises—and was Bravo ever a masterful poet.

He’s easily one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century. For this poetry is, of course, the magic of all the world's greatest photographers. Like a mechanistic fingerprint, no two photographic styles are ever really the same. Time, space, intuition, and the very act of looking all mark the poetry latent in the photographic medium.

One glance at Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light and it's obvious Bravo knew what he was looking for. Each Bravo artwork in this magnificent exhibit is an extraordinarily well thought-out composition where every visual element is accounted for; these physical elements being weighted against the tone of light, the density of light, the direction of light, the volume of light—and then there’s the poetry.

What’s left in the image is the world unto itself.

Granted, the time in which Bravo was working is romantic. Mid-20th century Mexico was a world where the natural and the supernatural seemingly melded together in a heady exotic brew and where the sacred and the profane coexist comfortably. There’s seemingly no separation between what is well and what is well-enough.

Born into an artistic Mexican family, Bravo was forced to terminate his education at the age of 12 when his father died in 1914. Studying accounting as he worked for the Mexican Treasury Department, Bravo freelanced photojournalism while learning the basics of art photography. It was through the friendship of fashion model and political activist Tina Modotti that he made contact with American photographer Edward Weston who in turn encouraged him to polish his craft.

Having lived through the Mexican Revolution of 1910-1920, Bravo was inclined to view his art through the prism of natural supernatural romanticism (and later surrealism) that marks early 20th-century Mexican aesthetics. As can be seen in the photographs of this exhibit, Bravo wrestled with the stereotypes that stamp much Mexican artistry while often using echoes of this stylization to comment upon them. Bravo's camera consistently catches these contradictions with a fluid grace that never editorializes while knowingly commenting on what’s depicted.

This means that every element of Bravo's photography is weighted against the composition's visibility as well as the reflection of Mexican culture as he lived and understood it. The result is indeed sheer poetry cum anthropology, as none of these photographs are never quite what they appear.

For example, Bravo’s 1977 gelatin silver print Señor de Papantla (“The Man of Papantla”) is a decidedly clever photograph whose background and meaning are richer than apparent in the already rich photograph of a Mexican campesino dressed in his best peasant garb. For the locale of the painting is as important as the image in that Papantla (in the state of Vera Cruz; in the Sierra Papanteca range, near the Gulf of Mexico) is famed as one of Mexico’s “pueblo mágico”—a city of particular natural beauty with historic and cultural relevance.

Bravo’s Señor stands stiffly with his sombrero tucked under his right arm posed in front of a nondescript stone wall. Standing under the diagonal right shade of a tree with his hair parted in the same direction to create an internal symmetry, of equal importance is his eyes cast away to the left in the same way. Averting the photographer’s gaze, Bravo’s Señor reflects the subdued unwillingness to cooperate that’s often characterized the citizenry of a country that’s seen centuries of repetitive political, social, and cultural upheaval.

By contrast, famed Mexican artist Frida Kahlo adopts an opposite stance for Bravo’s camera in her 1938 Frida with Globe, Coyoacan, Mexico gelatin silver print. Where the campesino was not directly addressing the camera, Kahlo challenges the camera by looking directly at Bravo. This act, of course, is in direct contrast to the Mexican sense of social propriety where the expectation would decidedly be a repressed feminine averral.

Even in the late 1930s, Kahlo (and by extension, Bravo) were having none of this modesty. Sheer appropriateness is drawn from her forthright respectability, as though the appropriateness of one’s behavior is as much one of correctness as it is self-respect. Seated with her left elbow propping her left hand against her cheek, Kahlo is everything she intends to be.

But Bravo is also addressing his audience in that a single subtle compositional element twitches the history of art anachronistically. For in contrast to Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas (where Velázquez paints himself painting the painting), Bravo eliminates himself from his photograph because there is no photographer reflected in the globe on the table next to Kahlo’s left. Surrealism was, of course, in full force in Europe at this time and Bravo opts to magically disappear in his own artwork.

If, however, one wants to find Bravo at the height of his power as a photographer, his famed 1932 gelatin silver print Retrato de lo eterno (“Woman Combing her Hair”) seals the deal. The exact translation of the title is “Portrait of the Eternal” and while the more prosaic “Woman Combing her Hair” is certainly accurate, the fantastic inference of “Portrait of the Eternal” is more enduring.

As I noted in the September 2002 UMMA Manuel Álvarez Bravo: 100 Years exhibition, Retrato de lo eterno captures Bravo at his haunting best. This darkly handsome portrait—of yes, a woman combing her hair—is everything its title says. Yet it’s also far more, as Bravo’s key lighting in this black and white photograph boldly exposes the model’s profile while also draping her in a controlled chiaroscuro where graded shadows create layer upon layer of profound mystery. The model’s self-absorbed beauty is veiled in an eternal mist.

Bravo’s Retrato de lo eterno is as much a staggering a work of genius today as it was in 2002. Just consider us lucky to look upon her likeness once again after fifteen years. If only because she’s indeed a portrait of the eternal—and this portrait will be so for a long time to come.

John Carlos Cantú has written on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

University of Michigan Museum of Art: “Manuel Álvarez Bravo: Mexico’s Poet of Light” will run through October 23, 2016. The UMMA is located at 525 S. State Street. The Museum is open Tuesday-Saturday 11 am–5 pm, and Sunday 12–5 pm. For information, call 734-764.0395.

Review: Civic Theatre spells hilarious, poignant with Putnam County Spelling Bee

Oh those middle school years, we remember them well. The humiliation, the anxiety, the bullies, the stress, the dire need to be good at something, what a wonderful time it was.

The Ann Arbor Civic Theatre is presenting a happy bit of nostalgia with The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, a musical salute to all those anxiety-ridden kids who strived to be top speller.

The Lydia Mendelssohn Theatre on the central University of Michigan campus is a perfect setting. The stage is simply decorated with a banner for the spelling bee, sponsored by the county optometrists, a riser of bleacher seats, a microphone and a table for the two adult hosts.

Spelling Bee takes a quirky, exaggerated look at some gawky budding adolescents and plays it for laughs that lead to some empathy and respect for the troubled young people who often get noticed for all the wrong reasons in school. Director Wendy Sielaff has brought together a fine cast that ham it up hilariously while also delivering the goods when called on to go deeper into character.

The music by William Finn is serviceable but the lyrics are used to convey those deeper feelings, while Rachel Sheinkin’s Tony-winning book richly skewers school life, spelling bees, and the cluelessness of adults.

We know the types. Here they are played not by middle-school-aged children but by older actors in reflection of those trying years.

Emily Fishman is sweet and appropriately apprehensive at Olive, dressed in an innocent pink jumper. Olive is torn between two neglectful parents and wants to finally get their attention. Fishman has a ringing voice, especially effective in "The I Love You" trio with her parents.

Nathan King is the goofy Leaf Coneybear, the non-achieving younger brother who gets no respect at home. But then again he dresses weirdly and shouts a lot. King brings a touch of Jerry Lewis to Coneybear but also some sweet pathos to "I’m Not That Smart."

Keshia Daisy Oliver is Logainne, the daughter of two gay fathers who want her to succeed a little too fervently. Oliver also finds the spot of empathy and a sweet moment of rebellion.

Bob Cox plays Chip, a boy moving into manhood at just the wrong time. Cox is dressed as a Boy Scout with too many merit badges. He is especially funny in "Chip’s Lament," a ditty about the betrayal of puberty.

Hallie Fox is Marcy, the over-achiever, the success-obsessed Catholic schoolgirl who sums up her anxiety with the song "I Speak Six Languages." Fox gives the character that determined to demented look and snappish voice of a future politician.

Finally, we come to the most outlandish contestant, Barfee (or as he insist, it’s pronounced Barfay). Connor Rhoades goes all out in his wrinkled white shirt, tie and shorts. Barfee is a big boy and the ultimate nerd who uses his foot to help him spell. Rhoades is a giant presence throughout but takes center stage with the "Magic Foot" number. He makes Barfee both anxiety ridden, pathetic, and strangely likeable. Rhoades also plays one of Logainne’s Dads (think Modern Family, here).

The other contestants are played (filled?) by good sports selected from the audience, who on Thursday provided some gentle laughs of their own.

The adult roles are also well played. Alison Ackerman is Rona, the teacher who never got over her success at the Bee. She is every bit the prim but enthusiastic teacher who misses the limelight. Ackerman also plays Olive’s absent in India mother in the "Love Song" trio.

Brandon Cave is excellent as the droll assistant principal Doug Panch who gives the spellers their words and much more. He gets some of the shows wittiest lines and he delivers them with low-key panache.

Finally, we have Nick Rapson as the coach who fills in as the sympathetic comforter of the “losers,” and he has just the right amount of sweet toughness and skepticism about the whole process. Thursday he had some humorous improvisation during his "Prayer of the Comfort Counselor" spotlight and made it special. Rapson also plays Olive’s Dad in the "Love Song" trio and is a hoot as Logainne’s other Dad.

Musical accompaniment by an on-stage five-piece band under the direction of Debra Nichols is solid, especially on some of the humorous percussion moments. Reilly Conlon brings the right clumsy humor and daffiness to the choreography.

Sielaff says this play has long been on her bucket list and now she can check it off as a success. She mines both the outsize humor and the quiet empathy that has make this a popular production across the country.

Hugh Gallagher has written theater and film reviews over a 40-year newspaper career and was most recently managing editor of the Observer & Eccentric Newspapers in suburban Detroit.

The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee continues at 8 pm Friday and Saturday and 2 pm Sunday at the Mendelssohn. For tickets and information, go online to http://www.a2ct.org, call (734) 971-2228, or purchase at the theatre before each performance.

Review: Theatre Nova's Dear Elizabeth

While watching Theatre Nova’s lovely new production of Sarah Ruhl’s play, Dear Elizabeth, drawn from 30 years of correspondence between poets Elizabeth Bishop and Robert Lowell, the phrase “alone together” comes to mind often.

Why? Because although they both experience love off-stage – Bishop with a woman in Brazil named Lota, Lowell with three different wives – their true first love is words; and like a jealous, possessive lover, words, when you’re a professional writer, demand that you spend most of your waking life alone with them, and only them.

So it’s not surprising that Lowell and Bishop – who lived a similarly isolated artistic existence, and consequently understood each other deeply – flung letters to each other as if they were life preservers.

In life, Lowell and Bishop wrote more than 800 letters to each other, offering praise and feedback for each other’s work; celebrating each others’ awards and personal victories; and chronicling their travels, as well as their battles with inner demons (Bishop’s depression and alcoholism, Lowell’s bipolar disorder). Not surprisingly, even the prose of their casual letters rings gorgeously poetic; in reference to a lighted swimming pool, Bishop wrote, “it is wonderful to swim around in a sort of green fire. One’s friends look like luminous frogs.”

The inherent challenge of an epistolary play, of course, involves giving the audience something to watch, not simply listen to. Ruhl lays the foundation for a visually satisfying production by way of stage directions, calling for occasional projections, and giving the actors a template for connecting scenes through actions; they also “live” certain quirky moments as they speak the words of their letters instead of pretending to write them.

But director David Wolber gets much credit, too, for adding his own creative touches, effectively using props, different areas of the set, and a movement pattern for the actors – partly inspired by Lowell’s frustrated observation that the two poets seem connected by a wire, so that when one moves, the other does as well – that keeps the audience engaged.

Another tricky prospect, however, involves how to present the poets in their moments of weakness, such as when Bishop pulls two filled wine glasses from her desk to drink. It’s initially funny, but when she then pulls out a bottle of rubbing alcohol and downs that, too, we know we’ve suddenly gone down the rabbit hole of addiction. Wolber and actress Carrie Jay Sayer handle the shift with sensitivity, not playing it too heavily or too lightly, but rather suggesting a haunting, all-too-natural progression into darkness. (Wolber specializes in plays about artists and the process of creation, so play and director are ideally matched here.)

Joel Mitchell is marvelous and heartbreaking as Lowell, a man who struggles mightily in his own life, and uses that as material for his confessional poetry. Sayer, meanwhile, is well-cast as Bishop, conveying the emotionally guarded poet’s simultaneous desire to connect to Lowell while also always maintaining an arm’s length distance; and the actress nails a running gag wherein, after showering Lowell with praise over a poem or collection, she pauses and says something like, “There are just three words I take objection to,” or “I have two minor questions.”

Similarly, Lowell critiques his letter-writing in a postscript – “The last part is too heatedly written, with too many ‘ands’ and so forth” – thus providing a glimpse of the writer’s particular brand of neurosis. But this telling moment also suggests why he and Bishop never find happiness for long: they each can’t stop trying to edit their own lives.

Carla Milarch designed the show’s sound (including key exterior noises), as well as its costumes (Mitchell pulls different jackets and sweaters from a coat stand on stage). And Daniel C. Walker designed the show’s lighting and set, with adjacent workspaces for each poet, a ladder upstage center, and a large, short rock downstage right.

Indeed, in Dear Elizabeth, the rock marks the spot where Lowell and Bishop spent time together on a beach one day in Maine, early in their friendship. In a rush of feeling, Lowell nearly proposed to Bishop there, and he later confessed this to Bishop, writing, “asking you is the might have been for me, the one towering change, the other life that might have been had.”

Though this is a beautiful, emotionally powerful admission to make, Dear Elizabeth makes you realize that in Bishop and Lowell’s case, Lowell’s failure to propose likely resulted in the pair having the most satisfying and durable kind of marriage they could ever hope to share with each other.

Jenn McKee is a former staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News, where she primarily covered theater and film events, and also wrote general features and occasional articles on books and music.

Dear Elizabeth runs through Sunday, September 25, at the Yellow Barn, 410 West Huron, Ann Arbor, MI, 48103. Call 734-635-8450 or visit Theatre Nova for tickets.