Review: Live from London: Les Liaisons Dangereuses

On Wednesday, February 17th, the Michigan Theater broadcast a stage performance of Les Liaisons Dangereuses through Britain's National Theatre Live. Directed by Josie Rourke, the production marks the 30th anniversary of Christopher Hampton’s adaptation of the original novel by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos.

Set in pre-revolutionary France, Les Liaisons Dangereuses tells the story of the beautiful Marquise de Merteuil, played by Janet McTeer, and the dashing Vicomte de Valmont, played by Dominic West, former lovers who now amuse themselves in a friendly competition of seduction and manipulation. The two are having a grand old time toying with their peers when the Vicomte unexpectedly falls in love with his newest mark, the virtuous and beautiful Madame de Tourvel (Elaine Cassidy).

The Marquise was the real standout in this performance. We so rarely get to see female characters like her: intelligent and witty, but also deeply flawed, scarred by her fight for independence. The Marquise is a woman who ruins the lives of others for petty revenge or jealousy, but who also fights ferociously to secure and defend her own freedom. Her ability to carry out her schemes in a world where the cards are so deeply stacked against women is a testament to her more admirable qualities. McTeer’s performance as the Marquise was incredible, bringing true range of emotion to a character that could easily have been played as a pure villain. West and McTeer had a definite rapport that underlined an unspoken jealousy between the characters that motivates many of the actions later in the play, as the personal stakes for the pair are quietly pushed higher and higher.

The sumptuous costumes and candle-lit scenes created a feeling of unsustainable decadence completely taken for granted by the French nobility. Within this splendor, the manipulative games played by the Marquise and Vicomte can almost seem frivolous. Their machinations ultimately boil down to trivialities, except that the emotions and lives of those involved, including the supposed masterminds, are so deeply affected. This production did an excellent job of laying out the emotional field of the characters, ensuring that each betrayal and revelation was felt like a twist of the knife, drawing the audience into a world where reputation and appearances are everything.

I entered this viewing with zero background for Les Liaisons Dangereuses, but I now understand why the play has been so successful. The story is well balanced, the events spooling out in a way that keeps you entirely engaged with the action. I think the secret of Les Liaisons Dangereuses is the attraction of watching a scandal develop before you, with no threat to your own reputation, almost like a guilty pleasure. Part of the reason the play is so effective is that you want to see what happens next, and so the audience is in some ways implicated in the games of the Marquise and Vicomte.

Audrey Huggett is a Public Library Associate at AADL and agrees with Dominic West that people look much more attractive by candlelight.

Review: Alvin Lucier: I am sitting in a room

Some might say Alvin Lucier: I am sitting in a room is not art by any means. But it is certainly right to say that it’s art by other means.

The Connecticut-based Lucier’s uncanny project—in the cutting-edge UMMA Irving Stenn, Jr., Family Project Gallery at the University of Michigan Museum of Art—is likely to be as underwhelming in its appearance as it is overwhelming in its accumulative cacophony.

The Stenn Project Gallery space has been stripped of everything except a few panels of soundproof insulation against its walls and armless couches for listeners to sit upon. Standing aside in the dimly lit gallery—and standing alone on a strategically placed black pedestal—is a single audio speaker. The only other thing left—as is sometimes said—is art.

Well, that’s to say, what’s left is a particular application of 20th century modernism because I am sitting in a room is as much creativity for the mind as it is an increasingly out-of-tune artful melody for the ear.

Lucier’s artistry—as minimalist in its execution as it is complex in its single-minded commitment—is analogous in spirit (though differing in execution) from the ambient replication of Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and La Monte Young. It’s an enigmatic industrial drone that has as much of an equal footing in proto-electronica as it does abstract conceptualism.

Originally crafted in 1969 at Brandeis University’s Electronic Music Studio as an experimental echo installation, Lucier’s intent was— and still is through its systematized multiplication—to scramble the physical property of soundwaves through the interrelationship of automated media and our human ear.

Composed in such a way as to make stumbling upon it a matter of chance, Lucier’s words unfold repeatedly upon themselves until their recurrence becomes indistinct. Increasingly incomprehensible as a verbal congruence steadily replicating itself, the result is a sonic environment whose totality is the aggregate of its texture.

Lucier narrates the following text:

“I am sitting in a room different from the one you are in now. I am recording the sound of my speaking voice and I am going to play it back into the room again and again until the resonant frequencies of the room reinforce themselves so that any semblance of my speech, with perhaps the exception of rhythm, is destroyed. What you will hear, then, are the natural resonant frequencies of the room articulated by speech. I regard this activity not so much as a demonstration of a physical fact, but more as a way to smooth out any irregularities my speech might have.”

That’s it, folks. Could anything be any simpler than this?

Well … the difference is in the details. After all, the Brandeis’ Music Studio in 1969 is not the same place as the UMMA Stenn Project Gallery today. And this means the work’s resonance will differ from the recording’s original acoustic setting.

Just as likewise, the sound of the recording will differ ever so slightly from the center and corners of the gallery depending on where you listen. There will therefore always be a subtle differentiation between each recipient of the source, the source of the transmission, and the transmission of the text itself.

An existential soundscape conditioned by its increasingly blurred repetition, the milieu plays a major part in the art itself. Lucier’s fragile reading—he has a discernible stutter—becomes progressively indistinct as his utterances are gradually blurred beyond recognition. But the cadence of his discourse also creates a peculiarly boisterous harmony through its replicated duplication.

It’ll admittedly take a bit of patience to sit through this masterwork, yet the experience is also going to be singular. Hovering uneasily somewhere between real-time and canned reiteration, I am sitting in a room is phenomenology as art gone nearly amok.

John Carlos Cantú has written extensively on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

University of Michigan Museum of Art: “Alvin Lucier: I am sitting in a room” will run through May 22, 2016. The UMMA is located at 525 S. State Street. The Museum is open Tuesday-Saturday 11 am–5 pm; and Sunday 12–5 pm. For information, call 734-764-0395.

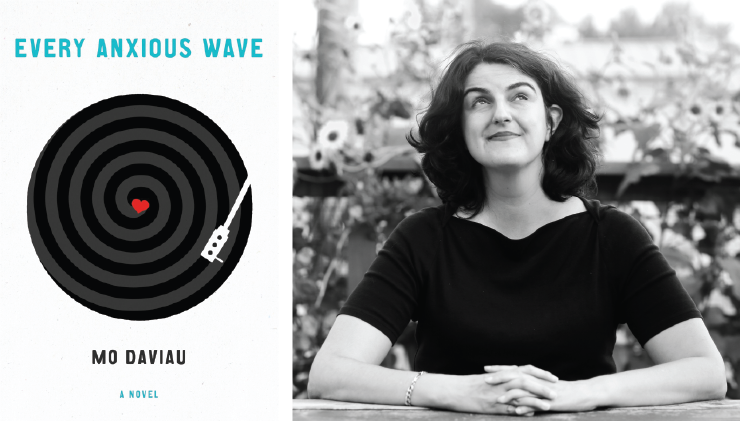

Time Travel Meets Indie Rock in Mo Daviau's Fiction Debut

When author Mo Daviau approached the podium at Literati Bookstore to read from her debut novel, Every Anxious Wave on Monday, February 15, she was friendly, enthusiastic, and eager to bring the audience in on the joke.

Her demeanor seemed well-matched to her subject matter - NPR describes her book as "a bittersweet, century-hopping odyssey of love, laced with weird science, music geekery, and heart-wrenching laughs." In it, 40-ish indie music fanatic Karl discovers a wormhole in his closet that enables time travel, and he uses it to send mega-fans back to experience concerts they missed - until a friend gets misplaced in time and Karl must connect with a prickly astrophysicist to untangle the problem.

Daviau started her talk with the confession that she'd recently heard from a reader who took issue with a character's trip to see the Traveling Wilburys perform live in 1990. The reader indignantly pointed out that the Traveling Wilburys never performed live, not in 1990, or ever. Daviau laughingly told the audience she'd come up with an explanation about the character technically crashing a recording session, but she good-naturedly thanked her concerned reader for pointing out her failure to properly research the performance history of the band.

Daviau's fiction debut was released February 9, but before that, it was a work in progress during Daviau's time in the University of Michigan's Helen Zell Writers' Program, where it won a Hopwood Award. The book carries a very sweet dedication to Daviau's father, who was 65 when the author was born, and who passed away when she was a young teenager. This is part of her inspiration for this story: because she had so little time with her father, Daviau says she thinks about time travel every day.

In her Q&A, Daviau said the discovery of a college radio station at age 11 started her on her love affair with indie rock. She came full circle with her early love of college radio by becoming a college radio DJ herself while attending Smith in the 1990s. She explained that main character Karl is some version of herself - but that she "found it easier to project feelings of regret on a schlubby bar owner" than on a woman like herself. But did she nail the male voice? "I just went for it," she admitted. "I'm interested to hear from real men how I fared with this." Reversing the question and answer portion, an obliging dude in the audience shouted, "Sounds authentic to me!" to the amusement of all.

Sara Wedell is a Production Librarian at AADL and might time travel back to see the Monkees Reunion Tour at Pine Knob in 1995, if only to get a t-shirt that's the right size this time.

Review: The Triplets of Belleville LIVE: A Real Treat!

The University Musical Society presented an amazing live performance of The Triplets of Belleville to a sold out crowd at the Michigan Theater on Friday night. The theater screened the movie while a live band played the soundtrack onstage. UMS announced this program on social media in February 2015, so I had a full year to look forward to it. Even with that anticipation, all my expectations were exceeded.

I was accompanied by my wife, my best friend, and my 88-year-old Grandma, who particularly loves The Triplets of Belleville. When the movie first came out, I walked into her house only to have my hearing almost destroyed by the soundtrack blaring from the speakers. She came downstairs with a triumphant grin and asked “Guess what CD I bought at Borders?!” It was not a hard guessing game.

For the uninitiated, Triplets is a 2003 animated film written and directed by Sylvain Chomet about the Tour de France, an aging jazz trio, the wine mafia, and the feud between an overweight dog and a train. In addition to its wonderfully strange story and delightful animation style, the film set itself apart by almost entirely eschewing dialog in its storytelling. The soundtrack, heavily influenced by jazz of the 1920s (but also prominently featuring Bach's Prelude No. 2 in C Minor), featured the Academy Award nominated song "Belleville Rendez-vous".

The first surprise of the live performance (to me; not to folks to read the event description more clearly) was that the conductor was Benoît Charest, who actually composed the soundtrack. It was amazing to see the person who had written the music that I love so much, and watching him conduct was a joy. In addition to conducting, he sang, played the guitar (and vacuum!), and danced along to the music. Charest also provided the French commentary for the Tour de France scenes.

The eight piece band, Le Terrible Orchestre de Belleville, was excellent and played in sync to the movie, occasionally looking up to the screen to make sure their timing was precise. At a few points during the show, the musicians got up and moved around to the center of the stage in order to play some of the more unusual instruments highlighted in the movie, including a newspaper, a cooking pot, and a vacuum cleaner. My favorite part was when the conductor, along with a few of the other band members, danced on a wooden board while clapping and snapping to create a rhythm section. After they pulled this off, they high-fived each other while the audience cheered.

The live performance of The Triplets of Belleville was an incredibly joyous event. The entire band seemed to enjoy themselves as much as the audience. Perhaps the only thing that could have made the evening better would have been a hound dog trained to act (bark?) out the role of Bruno, the movie’s lovable pooch. Of course, it’s highly likely that I’m the only person in the audience who would have liked this. Everyone I attended the performance with loved it, and the crowd was practically giddy as the theater emptied out. The music amplified the story and made each emotion shown on screen both stronger and sharper. My grandma called the night “a real treat.” I couldn’t have put it better myself.

Evelyn Hollenshead is a Youth Librarian at AADL and is interested in finding a local instructor for vacuum playing lessons.

Review: The Witch

Like most great horror movies, The Witch is smart enough to largely dispense with the “rules” of its genre. We see the film’s titular boogeywoman early on and with some clarity; we’re then led to believe that she may even be somewhat incidental to the plot, and that the true evil may be inside one of our seeming protagonists. There’s little gore and very little in the way of traditional “jump scares”–at least until it’s too late for The Witch to present itself as the kind of movie which traffics in such gimmicks. Instead of trying to engineer a shock-delivery system, The Witch opts for a slow-burning sense of dread echoing other great, unconventional horror flicks like Repulsion or The Shining.

The film is set in 1630 New England, as a family of seven is exiled from their Puritan colony for vaguely defined reasons related to the father’s (Ralph Ineson) “prideful” approach to spreading the word of God. The father, William, leads his brood to a spot just at the edge of a dark and expansive woodland and they begin to establish a homestead. Again neglecting typical genre practice, The Witch doesn’t allow us that typical dull period of calm when you’re waiting for the first scare to happen; we’re barely five minutes into the film before the newborn of the family vanishes during a game of peekaboo with capable teenaged daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy). Cut to the unsettlingly premature appearance of the decaying witch (Bathsheba Garnett) in her hut, performing some unholy ritual over the infant.

But is she the witch? Our highly superstitious protagonists immediately begin to suspect and accuse each other of being responsible for the baby’s disappearance, as well as the string of other misfortunes that begin to befall their settlement. And it’s hard for us to blame them. There seems to be some kind of evil in just about every member of this family–from the young twins (Ellie Grainger and Lucas Dawson), who openly converse with a goat they call “Black Phillip,” to William himself, whose determination to make the new homestead succeed verges on the deranged.

The small cast is uniformly excellent, convincingly wrapping their tongues around the knotty period dialogue. Ineson exerts a terrific gravitational pull as the all-powerful father slowly losing his grip, and Taylor-Joy gives a fierce, sympathetic performance as she becomes the film’s ostensible lead. The performers expertly craft a growing sense of hysteria that piles up into a final half-hour of protractedly spine-tingling scenes.

Production designer Craig Lathrop and costume designer Linda Muir work hard to create an authentic period atmosphere that makes the family’s dogmatic mania all the more believable. Although the vast majority of the film takes place in isolation on the family’s homestead, brief glimpses of their old colony at the beginning of the film have the fascinating feel of real life. First-time feature director Robert Eggers and cinematographer Jarin Blaschke collaborate to create a striking visual sense for the proceedings. Cloudy skies are omnipresent in the film’s many exterior scenes, and the color palette emphasizes grays and browns that feel earthy even as they seem to forebode decay and death.

And that’s appropriate, because The Witch is a film about people deeply connected to the earth, dependent upon it, but also fighting against their true nature. At one point the mother, Kate (Kate Dickie), emphatically expresses her wish that the family had never left their native England. For all William’s professed desire to serve God, he’s consistently ignorant of the universe’s signs that he’s doing the wrong thing. The presence, and possible wrath, of Native Americans hovers around the story as well. Local natives are seen for a fleeting but significant moment in an early scene, and a trade William made with them becomes a point of some contention among the family later in the story.

It’s easy to try to read The Witch as a theological text on the relative merits of the Christian God and Satan; the New York-based Satanic Temple, which has wholeheartedly endorsed the film, certainly seems to think so. But no. The film is about invaders trying to impose their will upon a land that was never theirs, and the land taking its own back. The Witch suggests a fundamental sin at the root of American history. Even more so than the standard genre tropes of a cabin at the edge of a creepy woods, or the old standby of God versus the devil, there’s true horror in that idea for any American.

Patrick Dunn is an Ann Arbor-based freelance writer whose work appears regularly in the Detroit News, the Ann Arbor Observer, and other local publications. He can be heard most Friday mornings at 8:40 am on the Martin Bandyke morning program on Ann Arbor's 107one.

The Witch opens in wide release this weekend.

Review: U-M's Clybourne Park Finds Deep Humor in Our Sad Racial Dance

It's still an awkward dance. When it comes to the subject of race, we seem to invent new language just to avoid the blunt words and ingrained feelings that are simmering just below the surface.

There are few places where that is more true than southeastern Michigan with a long, bloody history of racial animus. Flint and the Detroit school situation are just the most recent examples of the unresolved prejudices that politically correct speech can never hide.

The University of Michigan's School of Music, Theater and Dance couldn't have picked a more relevant and powerful play than Bruce Norris' Clybourne Park. But be warned, anyone expecting a sermon on race relations will find instead a hilariously serious comic drama. This is a play that exposes that awkward dance with sharp wit and a rare ability to understand the real complexity of the issue. The play has won the triple crown of theater awards, the British Olivier, Broadway's Tony, and the Pulitzer Prize and this U-M production is brilliant at making us laugh while unpeeling the many layers of code words that separate us.

406 Clybourne Street is the house in a white Chicago neighborhood that a black family moved into in Lorraine Hansbury's 1959 play A Raisin in the Sun. The first act of Norris' play set in 1959 centers on the white couple who have sold this home and are anxious to move out to escape the pain of the death by suicide of their Korean veteran son. The second act takes place in 2009 as an upscale white couple are meeting to discuss plans to modernize the now ravaged home in what has become a low-income black neighborhood.

This is serious stuff. But even in this first act director John Neville-Andrews uses Norris' stylized speech moving at a brisk pace, perfectly capturing the various anxieties at 406 Clybourne. The second act moves at an even faster pace, with more laughs but also more direct confrontation. His cast handles this very precise language skillfully, capturing every nuance of meaning and wringing every bit of the humor that dulls the deeper pain. In addition, each actor in the play has two distinctly different characters. That transformation is awesome.

In Act One, Jack Alberts is Karl, a leader of the community association, who comes to warn Russ and Bev that selling their house to a black family will lead to the end of their tight, white community. Alberts' Karl is a tightly wound, nerdy accountant type. He can't let a bad argument go, he can't let anyone else get a word in to dispute his notion that mixing races is a bad idea. His tight suit and undersized fedora perfectly highlight Alberts' performance. In Act Two, Alberts is Steve, a modern, hip guy, a real urbanite who wants to come back to the city and make it new again. This is where Alberts really nails the character, a slick guy who thinks he's post-racial, until he finds out he's not.

Lila Hood plays Karl's sweet, deaf wife Betsy, a victim of another kind of mindless patronization, and Steve's very modern wife Lindsey, an urban woman who claims at one point "half my friends are black." Again, Hood plays two characters who couldn't be more different and captures the sadness and isolation of Betsy and the whip-smart intelligence and total cluelessness of Lindsey.

David Newman goes from depressed father Russ in Act One, to broad comic punctuation as a construction worker in Act Two. His performance as Russ explodes as he makes a case that not all decisions hinge on the issue of race, even in Chicago. It is a plea for the personal over the social and political. His comic turn is a complete turn around.

Madeline Rouverol is the center point of Act One as Bev, a woman with high anxiety over the death of her son and the increasing depression of her husband. She talks a blue streak, she fidgets, she gushes. And when it comes to relating to her black maid, she displays the easy bigotry that passed/s for liberalism. She thinks she and the maid are friends, how quaint and how sad. In Act Two, Rourverol is a real estate lawyer, Albert and Betsy's daughter, who also thinks she's free of prejudice. Rouverol gets some very funny lines here that she places with pinpoint timing.

And about that maid, Francine. Blair Prince is devastating in this pivotal role. She presents herself as a dutiful employee, even as she is about to lose her job. But she's not one to be pushed around and she disdains Bev's phony liberal overtures (bribes), with looks that would wither a forest. When confronted by Karl to stand in for her race and answer his absurd challenges she dances to avoid and not offend while clearly showing that she is deeply offended. In Act Two, the tables have turned. She is the educated, tart tongued Lena, defending her community against its impending gentrification. It was her family who moved into 406 Clybourne. But here again, she dances around the issue until push comes to shove. Prince shows all of this in her expressive face.

Aaron Huey is Francine's kindhearted husband Albert, who shows that slowly dying deference to whites that makes old movies so uncomfortable. But Huey's Albert also shows his real feelings in his face and when things get a little too insulting he reacts with quick wit. As Lena's husband Kevin, he is a young professional at ease with whites, sharing similar interests, knowing the same people, sharing the same good life in Chicago. But as Act Two goes on, the bonhomie gets thin and then explodes and Huey masters that slow burn.

Jordan Rich plays Jim, a minister in Act One, who tries to straddle two contradictory ideas at once and do it with Christian charity. The temptation to overplay this sanctimony is avoided and Rich makes the character real. In Act Two, he's a building inspector who acts as a referee as the conversation moves from funny to dangerous. He gets one of the night's funniest lines.

The set design by Gary Decker is superb. In Act One, the house is a solid, old Chicago house, real wood trim, plaster walls. It's untidy only because the moving boxes are scattered about. In Act Two, fifty years of increasing poverty and the neglect poverty causes are evident in the home that is also in the early stages of demolition. The change is eye-popping.

Hugh Gallagher has written theater and film reviews over a 40-year newspaper career and was most recently managing editor of the Observer & Eccentric Newspapers in suburban Detroit.

Clybourne Park continues 8 pm Friday and Saturday, Feb. 19-20, and at 2 pm Sunday, Feb. 21, at the Lydia Mendelssohn Theater on the central campus of the University of Michigan. Tickets at the League Ticket Office, (734) 764-2538.

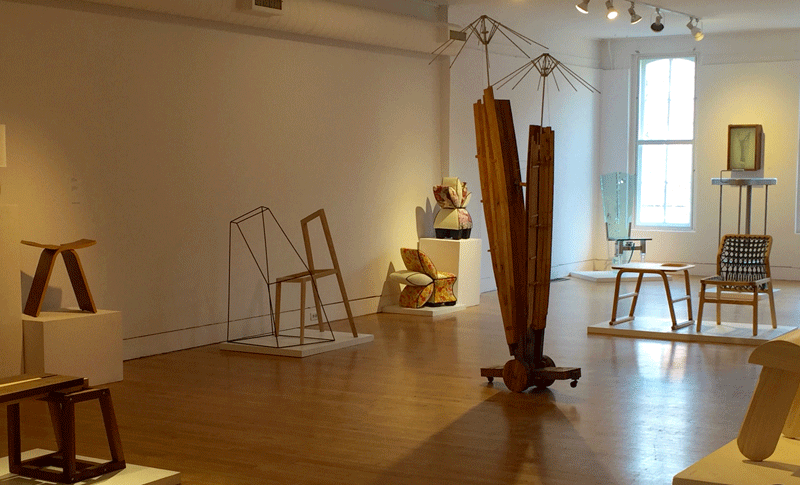

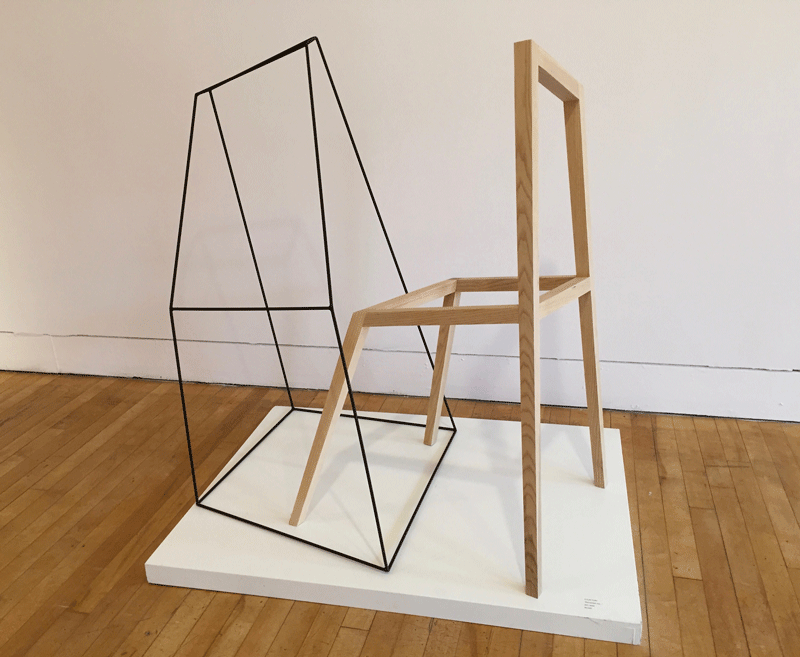

Review: Mid-West Furniture Zoku

If you enjoy challenging your notions of what is functional, what is craft, and what is art then you’ll find the Ann Arbor Art Center’s latest exhibition, Mid-West Furniture Zoku, especially engaging. While it is rare to view the collective works of local art furniture designers, do not doubt that this type of talent exists all around us. A deeply rooted and growing community, these are artists that earn their living either by making or teaching furniture design – or both. Once you learn about local modern masters such as these, you can further support them with your interest and by visiting their sites, both virtual and physical (really, call them up, plan a field trip, or just stop on by).

Exhibit co-curators and art professors John DeHoog, of Eastern Michigan University, and Ray Wetzel, of the College for Creative Studies, did an exceptional job selecting this concentrated, yet highly diverse grouping of artists and arts educators to represent “our regional clan of furniture makers, designers, and educators”, or our “Furniture Zoku”, to challenge preconceived notions. According to DeHoog:

“As educators we always look at exhibitions as having an educational role for students and for the public, so Ray and I wanted to collect work that was thoughtful, challenging, and in some cases provocative. The result is a group of objects that in my mind fall into the following categories: 1 – practical/functional, 2 – art furniture, 3 – sculpture that happens to use furniture, and 4 – conceptual.

While the viewers may not consciously pick up on the distinctions, I think they understand that there are makers working in certain common veins. Ray and I also made deliberate efforts to show ranges in scale (from miniatures to the very tall sculpture), ranges in material (wood, metals, fabric…) and ranges of mood (playful to serious). In all cases though, the level of craft is very high, and the love/respect for materials evident.”

In some cases, an artist’s work may be easily placed neatly in a single category. Others’ work may fall into two, three, or even all four of the categories mentioned by DeHoog.

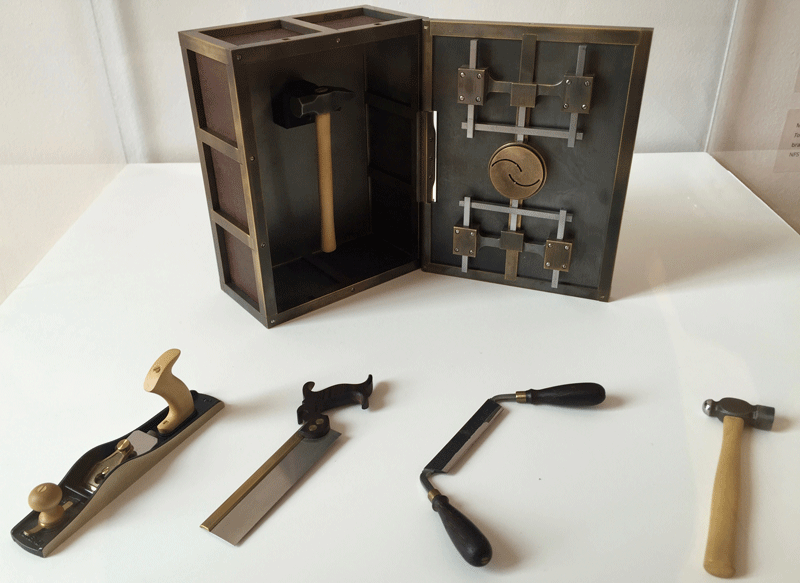

Detroit artist Marco Terenzi, a graduate of the Art Furniture program at the College for Creative Studies, creates work that defies categorization. His fully functional replicas of woodworking hand tools are impeccably articulated in quarter-scale miniature. Functional, though not practical, these pieces are becoming highly sought-after collectibles. The precision necessary to successfully accomplish this type of construction and functionality is mind-boggling, but Terenzi is intensely disciplined. He’s even replicated his workshop in fully functional quarter scale. And, at 25 years old, he’s only just getting started.

Detroit-based functional furniture and object designer, Andy Kem's Rand Table, made from American ash and molded cork, holds center stage in the main room of the exhibit. Kem has this to say about his approach to creating functional objects:

“Using wood, man-made wood products, and rapid prototyping, my work delves into two directions: on one hand more traditional craft techniques—but interpreted in nontraditional ways—and on the other, the use of digital tools to enable and realize new interactions amongst the parts that constitute the objects I create. In the merging of my different investigations, my work transcends function to arrive at a unique aesthetic language.”

Curator Ray Wetzel said about inviting Andy Kem:

“I wanted to bring the product design approach to furniture design and manufacture into the conversation. Andy has done quite a bit of work with c-n-c cut parts and manufactured raw materials. I've always liked Andy's work and his approach to design and maintaining craftsmanship. His work is formal, subtle and detailed.”

Also falling into the category of practical/functional, is the work of Ann Arbor-based furniture designer, John Baird. You may have interacted with his work if you’ve frequented local establishments like the AUT Bar or Salon 344. Reminiscent of old wooden classroom desks that conjure feelings of familiarity and durability, but with a modern and elegant edginess, Baird has on exhibit a prototype and finished version of the short-run, custom-fabricated stools he designed and produced for Comet Coffee.

On the subject of art furniture, it would be impossible for me not to mention the work of Maxwell Davis, Professor and Head of the Art Furniture Area at the College for Creative Studies, I mention it not only because (full disclosure) he’s my partner, but because he has also served as instructor and mentor to several of the other artists in this exhibit. More than his artwork, this to me is his most poignant contribution here.

One of the two works on exhibit by Davis is Chair #13, a glass and stainless steel chair that defies all intellectual, tactile, and functional logic. I love to see viewers reach out and run their fingers along this chair’s jagged-cut spine. The thick, raw edges of cut glass with their reflective waves and promise of danger, visually sewn together with rounded hot glass stitches, are near impossible to resist! The chair’s seat, back, and legs are all made from various forms of hot and cold glass, inviting the assumption that it doesn’t actually function as a chair. It does.

Presenting a temptation greater than touching the edges of broken glass, the most irresistible pieces in this exhibit to me, are those made by Aaron Blendowski. Blendowski is a Detroit-based furniture and object designer, who also works as Fabrications Coordinator at Cranbrook Academy of Art, and Co-Founder of OmniCorpDetroit. His Moderondack Chairs, made from natural and stained cypress, are joyfully oversized, simple and shapely; but not quite flawless. Their voluptuous seats are swimming with the natural detail of the textured wood grain that has been intentionally alternated during the process of gluing together the thick strips from which the chairs are constructed. The occasional knothole or indentation in the wood are left in plain sight. Finely-shaped and sanded to a smooth and shiny finish, I will neither confirm nor deny having broken a 117 Gallery rule while viewing these pieces.

Nicholas Stawinski may be the most unexpected furniture maker to fall into the category of art furniture, based on what we usually think of when thinking about upholstered furniture. A native of Detroit, Stawinski is an artist, furniture designer, and fourth-generation upholsterer who uses the post-industrial landscape of Detroit as his inspiration. Stawinski says:

“My work pays homage to the ottoman and footstool forms that I helped my father create in the back of our upholstery shop. Through recognizable shapes and the motifs of furniture, my ottomans contort and connect in ways that make the forms new and unfamiliar. Some of the fabrics I use reference specific interiors—such as my grandmother's living room in Michigan, where I would spend time while my father and grandfather worked in the shop downstairs— while others recall the endless parade of floral armchairs that marched through our door. Other shapes and patterns draw from memories of riding across Detroit in our delivery van, going to help little old ladies in retirement homes select fabric for their favorite chair, the one—they say—that will be passed on to their children and grandchildren. In this way, my ottomans are a celebration of the work ethic and skilled trade of upholstery, taught to me by my father and grandfather, as well as the way interior spaces shape our memories.”

I must also acknowledge my appreciation for the multi-faceted perspective on functional and conceptual furniture design of Detroit-based artist Colin Tury. While the highly graphic conceptual piece "Remember me…" made from ash and steel, is representative of Tury’s general aesthetic, it is but an ever so small glimpse of his overall talent as a furniture designer. Tury’s work easily traverses all categories from practical and functional to conceptual. It manages to be lanky yet graceful, and cautiously modest, while also conveying balance and confidence. Tury states:

“To me, craft is an important factor to our culture because it provides us a reminder that we are all still human and that we make things for a reason, not just to look at. Furniture specifically shares importance in that we are all unconsciously intimate with it throughout our day. Modern furniture has become a game of geometry in which designers compositionally arrange basic shapes and colors, and eliminate any feature beyond its basic function. We have lost all sense of material in a sea of powder-coated aluminum and veneered particleboard. I want to present material in furniture for its true nature, and highlight human error because it is a reminder that someone consciously created it. I strive to create conceptual meaning to all my pieces so that it can tell a story beyond its own physical existence. Materials play a big role in this because they have unique, yet specific, physical attributes that we can obey or abstract. A story can exist just in bringing two materials together in an interesting way.”

In my mind, the only truly disappointing aspect of this exhibit are the posted signs constantly reminding visitors not to touch the artwork, when the very nature of the work evokes the desire to touch and interact with it.

Because, after all, it is furniture.

Terry Soave is Manager of Outreach & Neighborhood Services and also coordinates exhibits at the Ann Arbor District Library.

"Mid-West Furniture Zoku" will run through March 5, 2016, at 117 Gallery at the Ann Arbor Art Center, 117 W. Liberty St., Ann Arbor, MI 48104. Gallery hours are Monday through Friday, 10 am-7 pm, Saturday 10 am-6 pm, and Sunday 12-5 pm. Artist and Curator Talk: Thursday, February 18, 6-8 pm. Co-curators John DeHoog and Ray Wetzel, along with some of the artists of Zoku, will talk about their processes and artworks from the exhibition.

Review: Ruta Sepetys on Salt to the Sea

Local young adult author and history fanatic Ruta Sepetys came to Literati on February 10th to discuss her newest work of YA historical fiction, Salt to the Sea.

The book tells the tragic story of teens Joana, Emilia, and Florian, refugees fleeing from Poland and the advance of the Red Army at the end of World War II. Each from a different background and a different country, their paths cross aboard the Wilhelm Gustloff, a real, historic ship that almost no one, including myself, seems to have heard of—despite it being the scene of the worst maritime disaster in world history.

Literati staff opened the evening with a quick introduction of the local author, making sure to mention that her novel Between Shades of Gray was the Ann Arbor/Ypsilanti reads book of 2014. Then Sepetys stepped over to the microphone to introduce herself, her background, and her newest story. Her enthusiasm for writing and storytelling was obvious, but it was clear by the way she lit up as she launched into the Wilhelm Gustloff's tragic tale that she was really in it for the history.

According to her avid research, the Wilhelm Gustloff was a German cruise ship that set sail into the Baltic Sea at the end of World War II packed with thousands of refugees searching for safety. The ship, designed to carry a maximum of 1,400 passengers, was filled with so many fleeing survivors that when it finally set sail, it carried 10,000 passengers, pressed into dining rooms, dance halls, and even the emptied swimming pool. Rooms meant to fit two contained 15 or 20 people. The ship was so heavy, it was forced to sail in deep water—and that's where a Soviet submarine found it and where three well-aimed missiles led to the world’s most fatal maritime tragedy, sinking the ship and sending 9,400 people to the bottom of the Baltic Sea.

Using only a handful of black and white photographs and her undeniable enthusiasm, Sepetys managed to paint a vivid picture of the tragedy and of her research process and keep the crowd completely rapt. With the flair of a master storyteller she managed to pull the audience into the story, hold us in suspense, impress on us the horror of the Gustloff's sinking—and then lighten the heavy atmosphere with a few anecdotes about her search for facts on the ship and its history.

Salt to the Sea was a mammoth effort in research for Sepetys, as she traveled to Poland and several neighboring countries to meet survivors of the disaster, hear stories from men who had dived the wreckage of the Gustloff, and wade through mountains of artifacts and heirlooms from those who lived the tragedy.

Sepetys explained that she chose to tell the story through characters from several different nationalities—Polish, Estonian, Lithuanian, and others—because she had found that the narrative of history could drastically change based on whose cultural experience was being told. You might write a book and think you know what it’s about, she said, but the story is really decided by the reader—and different countries can take one story in some vastly different directions.

She offered up her 2013 novel, Out of the Easy, as an example. Translated into dozens of languages, no two countries seemed to agree on what the book was about. Sepetys, when she wrote it, meant it to be about a girl living amongst the bordellos and brothels of 1950s New Orleans and struggling to shape her own destiny and make a life for herself outside of “The Big Easy.” But in France it’s marketed as a story of feminism in historical context. In Germany it’s a noir thriller. In Poland it’s about decisions and the dynamics that affect choice. And in Thailand, I kid you not, it is called The Hooker Book.

This diversity of interpretations fascinated Sepetys, and gave her a goal for this newest book: to show how the significance of a story could change from person to person, country to country. The author's genuine excitement was infectious and even the Q & A portion of the evening was entertaining as Sepetys enthusiastically answered questions from the audience and listened intently when audience members told their own family refugee stories. It was evident that the stories left the greatest impression on her and she made it clear that telling those stories was Salt to the Sea's main purpose. What exactly affects how history is shaped? Who decides how the stories get told and which stories get told?

Ambitious though it seems, Salt to the Sea works to tell a multitude of those stories within one, tragic story—history, as it is written by the victors and as it is written by the victims.

Salt to the Sea was released on February 2nd.

Nicole Williams is a Production Librarian at the Ann Arbor District Library and if she ever writes a book she is totally calling it The Hooker Book.

Feeling Cross: David Cross at the Michigan Theater

Downtown Ann Arbor shivered with excitement and near-frostbite as over 1,000 comedy-lovers flocked to Michigan Theater on Saturday, February 13 for David Cross's Making America Great Again tour. The return of this stand-up legend was an event not to be missed.

Even if you don't recognize Cross by name, it's likely you've encountered his work before. Maybe you've seen him in the cult tv show Arrested Development, heard his voice in the Kung Fu Panda series, or stumbled upon his sketch show W/ Bob & David on Netflix. He's kept busy over the last twenty years recording comedy specials, starring in The Increasingly Poor Decisions of Todd Margaret, and popping up in shows like Modern Family and Archer. One of my favorite little facts about Cross (there's no stopping this train now) is that he appears in both Men in Black and Men in Black II as completely different characters. (Not that you need an excuse to watch MIB.)

As a first-time visitor to the Michigan Theater, I was admiring my surroundings when someone extremely exciting took the stage to make an announcement. It was an American Sign Language interpreter. I couldn't help but wonder if this man would be interpreting the entire performance, because as a fan of David Cross's previous work, I knew what levels of vulgarity were possible. Where would the line be drawn for ASL interpretation?

Suddenly, the music got louder. Actually, it was deafening, but then I started picking up lyrics about a show...did I hear "David Cross?" I knew for certain this was the Making America Great Again theme song when I heard the phrase "turn off your cell phones or you'll be punched in the dick." This was going to be a good show.

Cross emerged with a beard even lumberjacks would envy. He wore a baseball cap, jeans, and a blue zip-up sweatshirt reminiscent of his Arrested Development Blue Man Group costume. Even Cross was completely entranced by the ASL interpreter. He tried a couple of test words, including "Ethiopia" and "Sputnik." Other, more...mature words definitely happened. This interpreter was legit.

Then came the traditional introductions, a time when performers compliment the town they're visiting to the delight of their audience. Cross mentioned that he'd been walking around town, and I later heard he'd been to HopCat. So what did David Cross have to say about Ann Arbor? "It's ok." He followed up with the question, "Is Ann Arbor still the most literate city in America?" and in response to audience applause, "Good for you."

Throughout the show, Cross paced along the stage, spouting what sounded like stream-of-consciousness commentary, jumping from one topic to the next effortlessly. His jokes reflected real life, from dysfunctional family gatherings to religion to politics. Surprisingly, despite the name of his tour, certain Republican presidential candidates were only mentioned in passing. More time was devoted to advocating for gun regulation; he sarcastically vented that "there's nothing more American than reading about a senseless...gun death."

Cross paused his ranting periodically to interact with an intoxicated audience member. Their banter seemed so natural that I started to wonder if she was an intended part of the show. Eventually, he gave in to her interruptions and handed her the microphone, and she sent her "peace and love to everyone." Cross, with total professional ease, chuckled and proceeded with his show saying, "So that was a little bit fun."

The night seemed to end before it started, and when it was over, Cross reemerged from backstage to take a group photo of the audience for his facebook page. If you missed the show this time, dry those tears! Rumor has it that Cross will record his performance on Friday, April 22 as a comedy special.

Kayla Coughlin is a Library Technician at the Ann Arbor District Library and is intrigued by American Sign Language possibilities.

David Cross returns to Michigan on Thursday, March 18, 2016, appearing at the Fountain Street Church in Grand Rapids.

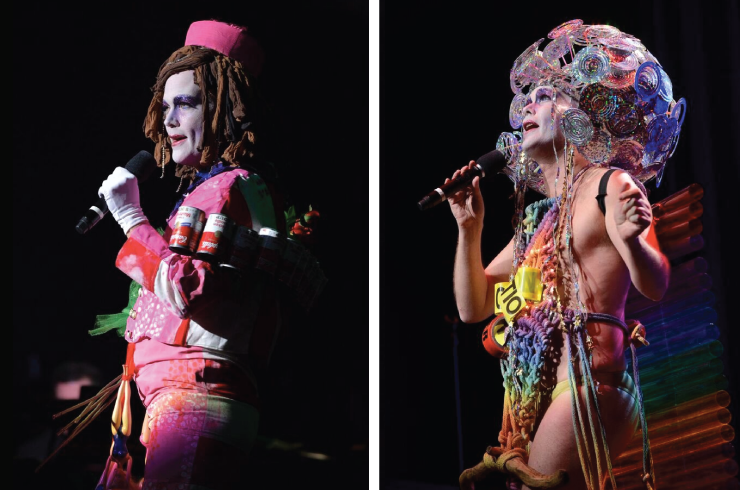

Review: You’ll Laugh, You’ll Cry, You’ll Learn Absolutely Nothing: Taylor Mac and His History of Popular Music

Taylor Mac is not a teacher. If you’re interested in learning history—take a class. Read a book. Get sucked deep into a Wikipedia black hole and hang out for a while.

On Saturday, February 6th, actor, performance artist, and drag queen, Taylor Mac gave a performance of his A 24-Decade History of Popular Music that made me laugh, made me cry, and made me extremely uncomfortable. The only thing it didn’t do was teach me any history. Which, considering just how much it attempted to do—and successfully managed—was not such a big surprise.

Hosted by the University Musical Society, the show was part stand-up routine, part concert, part drag-show, and part performance art. I have no words for this sort of performance amalgamation, and so I was perfectly willing to accept Taylor Mac’s own description of the event as a “radical fairy realness ritual.”

From the start, it was clear that the event would be unusual. Our host, Taylor Mac, came on stage in a hot pink skirt suit spray painted with an American flag on the back, a sash made of soup cans, and a jaunty little hat. Behind him on stage sat a band of seven musicians—a pianist, a bassist, a drummer, a guitarist, a guy who seemed to be playing a different instrument every time I looked at him (saxophone, trumpet, flute, possibly the flugelhorn), and finally, two exceptionally powerful back-up singers.

Mac began the show by explaining the bare bones of his musical project—each hour of the three-hour performance would be dedicated to a different ten-year period: 1956-1966, 1966-1976, and 1976-1986. Each decade came complete with its own costume, eight or nine songs from the time, and a central historic theme. This performance was just a fraction of a much larger endeavor Mac has planned for a later date, a 24-hour performance with an hour for every decade from America’s inception in 1776 all the way up to the glorious pop-fest that is the year 2016. Mac explained the idea that he would be on stage for a full 24 hours, singing and entertaining non-stop without food, bathroom, or sleep breaks, with the casual air of someone who is either very confident or incredibly irresponsible. Possibly both.

Probably both.

The first decade of our less-ambitious 3-hour show, ’56-’66, focused on aspects of the Civil Rights movement, or, as Mac puts it, “Songs Popular in the Bayard Rustin Planning Room.”

It kicked off with a slow and sultry rendition of Jay Hawkins’s “I Put A Spell On You.” By itself this would have been excellent entertainment—Mac’s stellar flair for theatrics is matched by his smooth, powerful voice. But just in case the audience had started to settle into the comfortable idea that they were at some tedious concert-meets-comedy-meets-drag-show, Mac introduced a new and terrifying element: audience participation.

After a very brief introduction of the racially tense atmosphere pervading the late ‘50s, Mac asked all of the straight, white people in the audience to stand up and slow-motion run to the sides of the room, simulating white flight.

“I understand that there won’t be a lot of room for you over there,” Mac said to the amazingly willing audience as they wiggled and stepped over each other to get to the sides of the room, “But I really want you to get the feel of the suburbs. I want you to be so close together that there’s a straight, white person on top of you even when you really don’t want a straight, white person on top of you.”

By the end of the song, I wasn’t sure if I was laughing, crying, or hyperventilating. If you’ve never seen a hundred people of all ages, including senior citizens, slow-motion run to the sides of a room and pack in like sardines, I highly recommend it.

With all of the elements fully introduced, the show really got under way. The ‘56-‘66 hour contained a bit of background on race issues and centered its attention on the March on Washington, though unfortunately most of the story that Mac told focused on the imagery of getting on a bus to go to the March. It involved an awful lot of audience playacting of getting to the bus/being on a bus/singing on a bus, without much actual information on the March itself.

Despite the fact that Mac didn’t tell much of a story, the music certainly did. The songs were well-chosen, a combination of Civil Rights anthems like The Staple Singers’ “Freedom Highway” and Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” and chart-toppers like The Supremes’ “You Keep Me Hangin' On” and Bob Dylan’s “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.” The songs that came with their own clear message, such as the impossible-to-misinterpret “Mississippi Goddam” were as powerful as you might expect. But even the popular hits, thrown in front of the backdrop of the 1950s and forced into context gave songs like Simone’s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” deeper meaning and even greater muscle.

I’ll admit it—the ‘56-‘66 decade was definitely my jam. But the following decades carried the same sort of structure and a lot of the same impressive weight.

Curtis Mayfield’s "Move On Up" transitioned us into the 1966-1976 decade, as Mac stripped down to a tiny yellow Speedo on stage, then disappeared behind the curtain and remerged in an outfit made up of so many different things that I honestly couldn’t tell if it was a dress, a jumpsuit, or if he’d tripped and fallen into a scrap box on his way back to center stage. The whole ensemble was tied together by a rainbow cape made of clear plastic tubes and a glittery silver headdress. This era had its eye trained on the beginnings of the gay liberation movement and the Stonewall riots of 1969. Songs included Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run,” Patti Smith's "Birdland," and The Rolling Stones' "Gimme Shelter."

The 1976-1986 decade focused on the idea of the '70s and '80s club scene and their infamous "back rooms." This aspect of history seemed like an odd choice until I realized that these "back rooms " were a prevalent part of Mac's own experience as he came up in the club scene. Dressed in a bright silver jumpsuit with a ruffled purple shawl and a shiny purple mohawk, Mac told his most personal (and most graphic) stories during this era in between Laura Branigan's "Gloria," David Bowie's "Heroes," and Prince's "Purple Rain."

The gaps between each song were filled with comic stories, musings, and, of course, the obligatory ridiculous activities that come with performance art. During the 1956-1966 portion of the show, audience members were asked to dance, march, engage in some pretty exaggerated crying, and, finally, to email Rick Snyder.

Sometime around the 1970s, we were handed ping-pong balls to throw at Mac as he ran through the aisles in his rainbow-tube cape and yellow Speedo. As we moved into the late '70s part of the show, Mac pulled an older gentleman up on stage and sang him a love ballad, while the pianist groped the man’s leg.

In the '80s, he had an entire row of the upper balcony come downstairs, go behind the curtain onstage, and emerge in ridiculous wigs, boas, and glasses and dance through the aisles. Each activity was a bit more unbelievable than the last, finally culminating in a college-aged boy standing patiently still while Taylor Mac kissed him and rubbed glitter lipstick all over his face. Permission was not asked, just a perfunctory, “You’re over 18, right?”

It was wonderfully weird, and, while the entire thing carried the feel of a glittery game of Russian roulette as we waited to see who would be Mac’s next participation victim, it also succeeded in doing exactly what Mac had told us it would—creating a shared experience for the audience. The audience was incredibly good-natured, dancing when asked, moving when asked, and making sure to applaud loudly and sincerely for anyone who was a good enough sport to obey instructions like, “go stand on stage, but don’t smile and don’t dance” or “lay down on the floor and let these five strangers carry you out of the room.”

From all this highly entertaining madness, I only came away with one critique. As a person who would have loved all the elements of this show even if they were completely separate and not one giant, Katamari Damacy-style ball-of-everything, I was absolutely enchanted by this performance, so much so that I didn’t even resent Mac for keeping me up past my 8 pm bedtime. Give me comedy, music, or drag any time of day and I’m game. But I was also interested in the promise of some really good history-nerd satisfaction, and so I was a bit let down by the minimal emphasis on the actual history.

While Mac did occasionally address the lack of historical fact—“If you want to know more about the March [on Washington…Google it. What about this outfit says anything more than Wikipedia?”—I felt like it was such a shame to dismiss the history so casually because of how much it could have brought to the show. Even the barest skeleton of historical facts would have ramped up the storytelling element and could have made this fun and flighty show a little bit stronger and a lot more engrossing, particularly in the gaps between musical numbers.

But considering how much it did do right, I really can’t fault it for the one thing it didn’t completely ace. The show managed to be a masterful musical performance, an entertaining drag show, and a surprisingly fun communal audience experience, so really, who cares if he didn't include a history lesson? It was still a performance I’m not likely to forget. At least, not in this decade.

Nicole Williams is a Production Librarian at the Ann Arbor District Library and, despite this positive experience, still thinks audience participation is the worst.