Penny Seats Theatre Company's "The Actors" is a comedic and emotional look at processing parental loss

Early in Ronnie Larsen’s play The Actors—staged by the Penny Seats Theatre Company at the Stone Chalet Event Center in Ann Arbor—a character says, “Theater’s weird. Families are weird.”

Ronnie, the comedic drama’s main character (who notably shares the playwright’s name, and is affectingly played by Brandy Joe Plambeck), voices this idea while explaining why he’s looking to hire a man and a woman to spend a few hours a week in his apartment, playing the roles of his deceased parents. He's lonely and has decided to use his inheritance money to hire actors that might make him feel cared for and connected again. Ronnie provides a family history and specific, remembered scenes for the actors to play out, inviting them to improvise.

Inevitably, though, things go hilariously off-the-rails, as the boundaries between reality and pretend get increasingly fuzzy. Ronnie’s stand-in father Clarence (Robert Schorr) and mother Jean (Diane Hill) develop an attraction for each other; Clarence moves in, after being kicked out of his real home; and Jean’s real grown son (David Collins) inserts himself as Ronnie’s pretend older brother Jay, which makes the real Jay’s (Jeffrey Miller) unannounced visit all the more painfully awkward. But Jay’s arrival also brings new information to light that throws Ronnie’s family memories, and motives, into question.

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: Two lost souls swimming in a fishbowl—another look at "Looking for Horses"

Stefan Pavlović's Looking for Horses is a glimpse into the real-life story of an unlikely friendship.

A fisherman named Zdravko was in the Bosnian War in the first half of the '90s and sacrificed his youth as a soldier. A grenade left him severely hearing impaired and another accident took his right eye. Director Pavlović grew up in Bosnia and was exposed to four languages, but he suffers from stuttering in his mother tongue Serbocroatian, which he understands imperfectly. The two friends are of different generations and temperaments and communicate in sometimes halting speech. Pavlović’s patient listening often allows Zdravko the opportunity to talk at length, reflecting on life and fishing strategies.

Zdravko spends his days on a lake in a small motorboat while Pavlović films him. We see the island church, now abandoned, where Zdravko lived for several years, surviving through the cold in a small sheltered room. Pavlović has joined him for his fishing adventures motivated by something else that remains hidden from us.

So many unanswered questions arise. How did Stefan and Zdravko meet? How does Zdravko live? (For all the time spent on the boat fishing, we never see him catch anything.) What do they each get out of their friendship?

But that’s not really the point.

If we knew the answers, would it change anything?

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: "Elephant" is a highly personal meditation on racism, violence, and trauma

The opening scene of Elephant shows a young Black woman at the inner entrance of her apartment, wiping away tears. Remnants of blood are visible on her body and the door. The movie is shot almost entirely inside this small apartment, where the protagonist, played by director Maria Judice, confines herself after experiencing something intense and distressing.

The scenes that follow unfold very slowly, without narration and with minimal sound. The pace and volume allow us viewers to linger on the details of the sparse surroundings. A second young woman—who we later learn is the protagonist’s sister—enters the apartment by the side door and begins to clean the apartment and quietly support her sibling.

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: "Rock Bottom Riser" digs into the cultural and physical roots of modern Hawaii

How fascinating to watch two movies back-to-back for the AAFF, both of them focused on different island chains. While Archipelago is about the myriad islands of the St. Lawrence River and often reflects a playful, calm mood, Rock Bottom Riser by Fern Silva is much more fractured and fraught with danger.

Through a collection of film segments, Silva explores some of the clashing cultural beliefs of modern Hawaii: spiritual, traditional, scientific. With little context or introduction, we see the people and places of Hawaii and are left with our own impressions.

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: The animated "Archipelago" traces the communities along the St. Lawrence River

What would you create if you wanted to convey the entire history of a place—the people with their personal struggles and giant conflicts, their loves and everyday lives, the music they listen to, and the story of the land itself?

Make a painting, write a novel, take pictures?

Archipelago, with its impressionistic mixture of animation and historic film footage, comes remarkably close to achieving the impossible task of capturing and reflecting the memories of a place on Earth.

Director Félix Dufour-Laperrière turns his attention to the islands and cities of the 800-mile-long St. Lawrence River to tell their stories and bring them to life. Admittedly, the St. Lawrence River, which originates in Lake Ontario in northeastern Canada, sounds like a dull topic for a feature-length film. But the vivid and wonderful expression of each stop in this fantastical travelogue is uplifting and hopeful.

Touching From a Distance: “A Thousand Ways (Part 2): An Encounter” explores emotional connections between strangers

After months of isolation and “Zoom socializing,” many of us are probably feeling pretty rusty when it comes to face-to-face conversations with strangers—which seems a raison d’etre of 600 Highwaymen’s A Thousand Ways (Part 2): An Encounter, presented by the Ann Arbor Summer Festival and the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

This intimate, interactive theater experience positions you and a stranger across from each other at a table, with a glass partition between you, in an empty room at UMMA. You take turns reading from a stack of cards—a black arrow indicates which of you the card is for—and you read aloud from it, or follow instructions like, “Imagine what keeps this person up at night,” or “wink with each eye,” or “with your partner, make a box with your hands against the glass.”

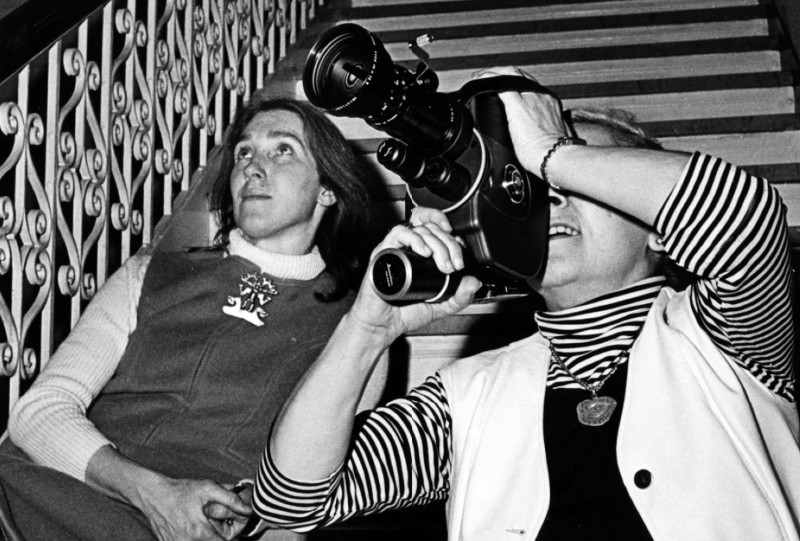

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: Documentary gives due to avant-garde film pioneer Sally Dixon

Filmmaker, enthusiast, advocate, meticulous curator, promoter, free spirit and nurturing mother of avant garde film.

Those are the words used to describe Sally Dixon in Brigid Maher’s documentary Experimental Curator: The Sally Dixon Story.

Dixon’s role as filmmaker, advocate, and curator of films at the Carnegie Museum made her a key if less-known figure in the emerging experimental avant-garde film movement. Her work was crucial to gaining recognition and financial backing for such key figures as Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, Bruce Baillie, James Broughton, and Kenneth Anger. She was also an advocate for women filmmakers such as Carolee Schneemann. Women filmmakers often found it difficult to gain acceptance in the male-dominated field. Dixon opened doors for them.

The Ann Arbor Film Festival will screen Maher’s feature documentary at 1 p.m. Sunday, March 27, in the main auditorium of the Michigan Theater. The documentary will be followed by four short experimental films: Fist Fight by Robert Breer, Valentin de las Sierras by Bruce Baillie, Invocation of My Demon Brother by Kenneth Anger and Take Off by Guvnor Nelson.

The Ann Arbor Film Festival has long been a major home for experimental film. This documentary should be just the ticket for those seeking a little history on a movement that had a whole different view of what movies could be about than Hollywood.

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: "Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over" is a revealing look at a confrontational avant-garde icon

The title of director Beth B's film Lydia Lunch: The War Is Never Over derives from an archival performance clip in which Lunch, a confrontational New York City no-wave musician, performance artist, and icon, dissects the endless masculine predilection toward war. "You want to go on a suicide mission? Go on a suicide mission," Lunch says. "One man, one bomb, and leave the innocent women, the innocent children, and the innocent male civilians out of it. It's not my war."

But the title takes on greater significance as B and Lunch delve deeper into a very different kind of never-ending battle: Lunch's efforts to grapple with her childhood sexual abuse and resulting trauma. They take their time getting there, ping-ponging in a free-associative format between topics including Lunch's various musical projects, activism, and use of sex as a weapon and instrument of subversion.

Now 62, Lunch is as much a force of nature as ever, rattling off poetic, angry, profane, and blackly funny rants with unfettered savagery directed toward the patriarchy and other institutions of oppression. "Lydia is a fuckin' doctor," musician Carla Bozulich says in one of the film's many interviews with Lunch's kindred artistic spirits. "Her kind of medicine is just a punch in the fuckin' face."

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: Two lost souls meet on a small Bosnian island in "Looking for Horses"

Stefan Pavlovic’s Looking for Horses begins in a deep mist and heavy clouds. The image, shot with a hand-held camera, shifts wildly, moving from choppy lake waters to a menacing sky of black clouds.

This sets the tone for a film about a rich, emotional friendship between the young filmmaker Pavlovic and a reclusive Bosnian fisherman.

Pavlovic is a filmmaker based in Amsterdam. He returned to his family’s native home of Bosnia where he met the fisherman, Zdravko, who has been living alone on a small island for 18 years. He rarely goes into the nearby town of Orah. He has set up living space in an abandoned chapel over the last five years, having lived in small shacks around the island.

Zdravko was a soldier in the Bosnian war. He lost his hearing. Later he lost sight in one eye in an accident. His face is deeply wrinkled. He smokes cigarette after cigarette. He’s gruff but welcomes the attention of the young filmmaker, touched by the idea that he would be a worthy topic for a documentary.

60th Ann Arbor Film Festival: Japanese documentary "Shari" is an empathetic, dreamlike look at a changing planet

The subject of Japanese director Nao Yoshigai's Shari creeps up on you as unexpectedly as the hulking, crimson, woolly creature that shambles through the film in a series of dreamlike interludes. The film focuses on the Japanese town of Shari in 2020, and at first seems to be a series of well-observed vignettes chronicling the lives of its residents. But as we meet the townspeople—a baker, a fisherman, an eccentric art collector—they all return to a common topic: the tension between human life and the natural world. Shari's residents discuss feeling drawn in by their town's natural beauty, but they also describe a delicate push-pull between conservation, tourism, and industry. One resident offers the metaphor that Shari's natural resources are a principal upon which people should collect interest, rather than squandering the initial investment.

Shari's residents are also all preoccupied in different ways by the same anxiety: the town has experienced its lightest snowfall in 40 years. There are fewer fish in the ocean, plant growth is stunted, bears are skipping hibernation because they can still find food, and the townspeople have an overall sense of unease.

Things are not as they should be.