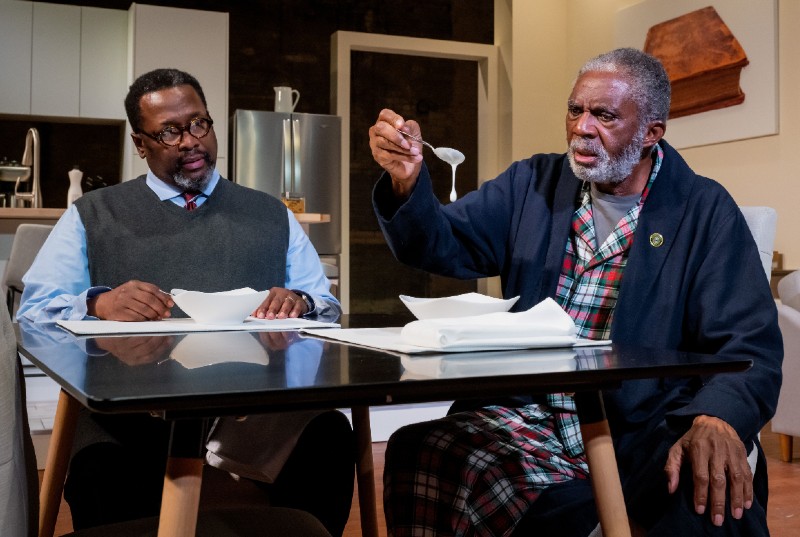

UMS's stage-film hybrid production of "Some Old Black Man" explores race and generational conflict

This review originally ran on January 19, 2021. We're featuring it again because UMS is streaming "Some Old Black Man" for free March 1-12, 2021, but you have to register for the screening here.

The closer we are to someone, the more likely we are to engage in picayune arguments that quietly scratch at, and chafe against, far deeper issues.

Which is to say, a family clash about what to eat for breakfast—a conflict that kicks off early in the recently streamed University Musical Society theater production of James Anthony Tyler’s two-hander Some Old Black Man—is often about something else entirely.

In the case of NYU literature professor Calvin Jones (Wendell Pierce) and his ailing, 82-year-old father, Donald (Charlie Robinson)—who’s just been relocated from his home in small-town Mississippi to Calvin’s posh Harlem penthouse—a conflict about a yogurt parfait strikes notes of really being about control, and conflicting generational perspectives, and blackness, and ego, and masculinity.

That is an awful lot for a soupy bowl of granola and fruit to carry.

But Tyler understands that to mine down to the heavy, hard-to-face stuff, humans inevitably have to start the process by hacking away at nonsense for a while—with absurdly tiny pickaxes.

No Slowing Down: Ann Arbor cartoonist Dave Coverly celebrates the 25th anniversary of "Speed Bump"

The easy part of compiling a book that celebrates a comic strip’s silver anniversary is, well, you’ve got lots of options.

“I’ll get reviews and comments that say, ‘Not a clunker in the bunch!’—but, you know, I had 10,000 to choose from,” said Ann Arbor-based cartoon artist Dave Coverly, whose book Speed Bump: A 25th Anniversary Collection debuted in September. “If anyone wants to visit my house, you could see a big plastic tub of cartoons that are terrible.”

Perhaps that’s inevitable when your job’s required you to hatch and execute seven new ideas every week throughout two and a half decades. “You can’t wait for the muse to strike when you’re on deadline,” Coverly noted.

But having the National Cartoonists Society award your work with Best in Newspaper Panels (’95, ’03, ’14) in addition to its highest honor, the Reuben Award (’09), might suggest that you’re getting it right far more often than not.

And for Coverly, one of the most appealing things about a single-panel cartoon is its unfettered flexibility.

“I do a lot of cartoons that use aliens and animals, but they’re always really about people and the things we all have in common,” said Coverly. “My daughter, who’s a painter, had a professor who told her, ‘Don’t ask yourself what you’re going to paint. Ask yourself why you’re going to paint it.’ And I love that quote because I’m someone who—I don’t like jokes for the sake of jokes. … I’d rather try for something that’s driven by an idea. Something that’s more subtle.”

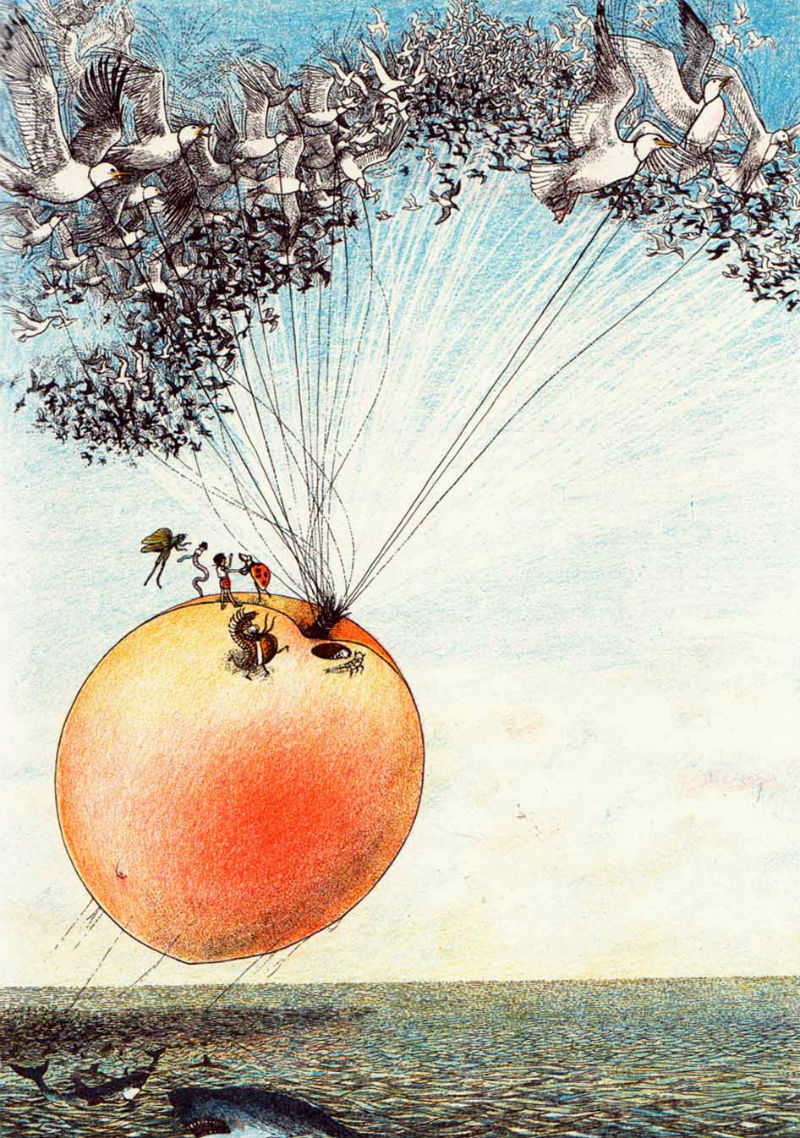

Encore Theatre's junior production of "James and the Giant Peach" finds a way to make everything better

Perhaps it’s a sign of how trippy a moment we find ourselves in that the work of Roald Dahl seems suddenly, particularly ubiquitous.

For just as a touring production of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory continues its run at Detroit’s Fisher Theater, regional productions of the James and the Giant Peach stage musical -- with a book by Timothy Allen McDonald, and music and lyrics by U-M grads and Oscar, Tony, and Grammy Award winners Benj Pasek and Justin Paul -- have been sprouting up everywhere, including at Dexter’s Encore Theatre.

Encore’s junior production, which begins February 28 and runs for eight performances through March 8, features 22 young performers, ranging in age from eight to 18.

“One of the things I love about [the show] is, not just the chosen family aspect of it, but also, James has this ability to be dealt a terrible hand constantly, and yet he always finds a way to make it better, and always finds the good in things that other are quick to overlook and discard,” said Matthew Brennan, the director of Encore’s production. “The insects, for example, these pests people just want out of their house. … [H]e finds potential in them, and that speaks to something really cool about this story.”

Invisible Touch: "As Far As My Fingertips Take Me" explores the universal refugee crisis through a one-on-one encounter

Whenever I see news footage of refugees, I always think, “How bad would things have to get before I packed a bag and fled from my home?”

The answer, of course, is really, really bad, especially when doing so would likely put me in mortal danger and leave me vulnerable, indefinitely, in countless ways.

So I knew that As Far As My Fingertips Take Me -- a one-on-one installation performance that’s part of University Musical Society’s No Safety Net 2.0 theater series -- would likely challenge me and make the pain of diaspora more tangible. But what I couldn’t have guessed is how strangely attached I’d become to the visible marks it left upon my skin.

Created by Tania Khoury and performed by Basel Zaraa (a Palestinian refugee born in Syria), the experience begins when you bare your left arm to the elbow, sit next to a white wall, pull on a pair of headphones, trustingly extend your arm through a hole in the wall, and listen to a recording of Zaraa telling his own refugee story, accompanied by an atmospheric rap inspired by his sisters’ journey from Damascus to Sweden.

Take Comfort: Jeff Daniels and Purple Rose Theatre's "Roadsigns" is like a '70s folk song come to life

For more than a quarter-century, Chelsea’s Purple Rose Theatre has specialized in new plays that don’t normally require a music director.

That's why I was initially surprised to hear that a musical (or “play with music”?) called Roadsigns would have its world premiere there.

But then I quickly remembered the theater’s movie/Broadway/TV star founder, Jeff Daniels, has been performing his ever-growing catalog of original folk songs as an annual fundraiser for the Rose, and his son, Ben Daniels, is a professional musician in his own right.

Then the whole notion of a Purple Rose musical felt not just sensible but downright inevitable.

We're All Crumpet Now: Kickshaw Theatre's production of David Sedaris' "The Santaland Diaries"

Despite the clichéd, eye-roll-inducing notion of creative work that makes you laugh and makes you cry, David Sedaris’ essays are nearly universally adored because they regularly, miraculously achieve just that.

This has become particularly true in recent years as Sedaris has explored, with bracing candor, the painful aftermath of a sister’s suicide and grappled with his complicated relationship with his aging, politically conservative father.

Yes, Sedaris and his craft have both come a long way since his hilarious, breakout 1992 radio essay “The Santaland Diaries” -- chronicling Sedaris’ work experience as a Macy’s elf in New York City during the holidays -- premiered on NPR’s Morning Edition. It’s since become a kind of subversive holiday classic, up to and including a one-man stage adaptation by Joe Mantello that’s now being produced (in Ypsilanti) by Kickshaw Theatre.

Judy, Judy, Judy: Taylor Mac’s "Holiday Sauce" is a mischievous feast for the eyes, ears, and soul

Usually when I see a show for review, I don’t end up on stage, singing a Pogues song.

But then, most shows are nothing like Taylor’s Mac’s Holiday Sauce, which UMS brought to the Power Center on December 14 and 15.

Mac has so many talents that I’d wear out my hyphen key if I tried to list them all. A MacArthur “Genius” and finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, Mac created Holiday Sauce as a tribute to the playwright-singer-artist's drag mother, Flawless Sabrina. “She used to always say, ‘You’re the boss, apple sauce,” Mac said, referring to the show's title, and Sabrina regularly hosted "judy" and others during the holidays. (As Mac told the Los Angeles Times, "[M]y gender pronoun is 'judy’ because I wanted a gender pronoun that is an art piece.”)

And indeed, Mac’s final elaborate ensemble for the evening, which made judy resemble a majestic, snow-covered peak, featured what looked like a formation of tiny pine trees that spelled “BOSS” down the gown’s back.

Mac wore this while performing the show’s quietest and most personal number, “Christmas at Grandma’s,” wherein judy sat alone on stage and played ukulele. The darkly comic, ironically jaunty song chronicled what the holidays were like when judy was annually dragged to visit homophobic relatives who were themselves struggling with past sexual abuse, a serious head injury, and alcoholism.

So … a Norman Rockwell painting come to life, right?

But that’s the point, of course: While we’re all confronted each year by cultural depictions of perfect families joyously celebrating the holidays together, the reality is that a good number of us identify far more with the inhabitants of the Island of Misfit Toys.

The Cost of Joy: "A New Brain" is odd, lovable, and filled with ear candy

“Sometimes joy has a terrible cost" is a quintessential lyric in William Finn’s autobiographical musical, A New Brain.

And in the production staged this past weekend at the Arthur Miller Theater by the University of Michigan Department of Musical Theatre, creatively blocked composer Gordon Michael Schwinn (Jack Mastrianni) gets an existential jolt of electricity by way of an unexpected, scary brush with death.

For just as Gordon struggles mightily to write a song for a children’s television show frog named Mr. Bungee (Matthew Sanguine), he meets up with his agent and best friend Rhoda (Brianna Stoute) for lunch and suddenly loses consciousness. After various tests, a hilariously blowhard doctor (Hugh Entrekin) tells Gordon he needs a craniotomy, and this scary news sends Gordon, his mother Mimi (Madeline Eaton), and his lover Roger (Luke Bove) into an emotional tailspin.

While this may not sound upbeat and lighthearted, A New Brain -- which premiered Off-Broadway in 1998, with music and lyrics by Finn, and a book by Finn and James Lapine -- is a kind of odd, lovable, small, shaggy dog of a musical. Because the primary narrative’s series of events is markedly compact (Gordon’s collapse, diagnosis, surgery, and outcome), the 90-minute show opens its doors with some quirky turns, providing space for fanciful character tangents (like “nice nurse” Richard’s lament, “Poor, Unsuccessful and Fat”), minor characters (a homeless woman), and frog-haunted flights of hallucination and memory (“And They’re Off,” which fills in the blanks on why Gordon’s father isn’t part of the picture).

Inspired by Finn’s own arteriovenous malformation diagnosis, in the months following his Tony Award-winning success with Falsettos, A New Brain is a flawed but endearing confection. For every seeming misstep -- to name one, the homeless character never wholly justifies her sizable footprint within the show (even though Daelynn Jorif’s vocals wowed me) -- there are several brilliant little strokes of wit, surprise, and warmth.

Encore Theatre ably explores "The Secret Garden" despite the play's storytelling woes

Generally, when we’re suffering and in pain, we know the cause.

But when it comes to identifying what will heal us -- let alone knowing whether healing is even possible -- that’s another matter entirely.

This all-too-human struggle makes up the core of the 1991 stage musical adaptation of The Secret Garden -- book and lyrics by Marsha Norman, music by Lucy Simon -- on stage at Dexter’s Encore Theatre.

Inspired by Frances Hodgson Burnett’s classic 1911 children’s novel, the story begins -- rather confusingly, to be honest -- with a young British girl, Mary Lennox (Jojo Engelbert), surviving a cholera epidemic that leaves her an orphan in India. She’s dispatched to the country home of her Uncle Archibald (Jay Montgomery), but he doesn’t bother to greet her, so steeped is he in his own grief for his deceased wife, Lily (Sarah B. Stevens).

Mary’s only company at first is a maid named Martha (Dawn Purcell), but then Mary befriends Martha’s nature-loving brother, Dickon (Tyler J. Messinger), who feeds Mary’s curiosity about the walled-off, locked-up secret garden that was once loved and tended by Lily. Plus, Mary soon stumbles upon another young resident of the house: sickly, bedridden Colin (Caden Martel), who fears that his father, Archibald, hates him because his birth caused Lily’s death.

If this all sounds pretty dark and gloomy, well, it is.

Regrets, He's Had a Few: Former Wolverine and NFL wide receiver Braylon Edwards is forever "Doing It My Way"

Former University of Michigan All American wide receiver and NFL Pro Bowler Braylon Edwards has a reputation for being outspoken, to say the least. But even so, he had to warm up to the idea of writing Doing It My Way: My Outspoken Life as a Michigan Wolverine, NFL Receiver, and Beyond.

“Triumph Books, my publishing company, originally approached me in 2017,” Edwards said. “I had no idea what my book would be about, and to be honest, at the time, the money was laughable. … So we said, ‘We’ll pass.’ And by we, I mean me and my mother. She’s my business manager, so I run everything by her. But as we started telling people that I was presented with this opportunity -- my aunties, my uncles, my cousins, my coaches, my friends, everybody -- I started to think there enough things I’ve gone through in my life that make my story unique.”

This included constantly traveling between two sets of parents as a child; being a “legacy” athlete since Edward’s father, Stan Edwards, played football for Michigan under Bo Schembechler; the ups and downs of Edwards’ football career, both at Michigan and in the NFL; and his struggles off the field, including his battles with drug use, anxiety, and depression.

“It became evident that the book should happen -- that this was something we should definitely sign up for,” Edwards said. “So when [Triumph] came back to us in 2018, I didn’t care so much about the money. It was more about my story out there. … People forget that there’s more to athletes than a helmet, or a golf club, or lacrosse sticks -- especially now, with social media and fantasy sports. It’s like no one cares about athletes anymore. It’s all about, ‘What can you do for me?’”

Edwards wrote Doing It My Way with ESPN’s Tom VanHaaren. And while you might assume that Edwards felt a bit nervous and vulnerable when his highly personal book debuted in September, that’s not the case.