U-M Lecturer Philip D’Anieri's Book Maps the Appalachian Trail Through the Stories of Its Developers

The 2,000+-mile Appalachian Trail spans the eastern United States from Georgia to Maine, traversing 14 states in total. The trail looms large in the consciousness of many people, from sightseers to thru-hikers. But how did such a major trail get created?

U-M lecturer Philip D’Anieri shows how the Appalachian Trail could not exist without the significant effort and devotion of instrumental individuals over time in his new book, The Appalachian Trail: A Biography. He provides not only facts about the contributors’ lives but also insights into who they were and what motivated them to contribute to the AT. D’Anieri also examines how the AT forms and fits into our views of nature.

Each chapter outlines how a different person (or people) helped shape the trail’s establishment. The trail’s development occurred alongside the growth of the United States, causing conflict when the trail was at odds with roads, politics, or interests of private landowners. The story begins with Arnold Guyot’s mapping of the Appalachian Mountains, as published in an article in 1861. In subsequent years, various individuals explore and build miles of trail, from the librarian Horace Kephart to Benton McKaye’s coining of the name “Appalachian Trail” in the early 1900s.

The first thru-hikers, Earl Shaffer and Emma Gatewood in 1949 and 1955, respectively, influenced the use of the AT. Another chapter depicts Senator Gaylord Nelson, who introduced legislation to federally protect the trail in the 1960s and also founded Earth Day in 1970. The book goes on to describe the challenges and successes of the National Park Service, which sought to obtain land along the AT’s corridor. Bill Bryson’s bestseller, A Walk in the Woods published in 1998, drew many to the trail, as D’Anieri writes in the penultimate chapter.

At the start and end of the book, D’Anieri reflects on the Appalachian Trail’s meaning in the public consciousness and his own engagement with the trail. In the introduction, he writes:

The places we choose, and the way we then develop and manage them, tell us a lot about what we are asking from nature, what exactly we think we are traveling toward and escaping from, where we want to strike the balance between maddening civilization on the one hand, and heartless nature on the other.

This question sets the stage for studying various individuals’ involvement in the AT’s construction.

D’Anieri finishes the book by discussing his adventures in driving the length of the trail and hiking short sections. His points that the Appalachian Trail is for everyone, and that there is much value to walking rather than driving, offer a current take on the trail. There is a great opportunity to interact with nature via the AT, to step away from our existing lives for a different outlook.

I interviewed D’Anieri to learn more about his book and the process of writing it.

Zilka Joseph’s new chapbook, "Sparrows and Dust," finds parallels between humans and birds

What would it be like to be a bird?

Ann Arbor poet Zilka Joseph’s new chapbook, Sparrows and Dust, imagines the parallels between human lives and the patterns of birds.

Birds become a constant in the poet’s life, from India to Michigan. Like the migrations of birds from place to place, the last poem begins with a description of the vastness of our collective lives and the places where we spend them:

Between Worlds,

and in worlds within worlds,

we live.

Throughout Joseph’s poems, all creatures are trying to make their way in the different places that form the settings for their lives. There are the geese and the poet observing them, and they are all distressed after five eggs disappear one spring. Yet being able to watch that drama play out is the result of a happy milestone of moving into a new condo for the poet.

Another poem, “Negative Capability,” wonders at flight:

open sky sun so night comes stars wheel

we spiral higher become air is this

the bird way

Arrivals and departures, and worlds appearing or disappearing, happen through flying. A hummingbird visits in another poem, “So Much,” to get “one more hit of her liquid / sugar high ill- / usion on which / her flight / depends.” Slowly we piece together what flight might be like, what sustains it, and what possibilities it offers.

Joseph’s poems sometimes alight on the birds themselves and other times show birds as metaphors, such as in the poem “Mama, Who’d Have Thought,” which speaks to the poet’s mother on how birds of prey are not a threat to safety but how police shootings and detaining children at the border are. In fact, many of the poems offer reflections on the poet’s parents.

These poems hold many moments for the admiration of nature. “Fall Now” describes that “we count kestrels overhead / one monarch sits in my palm.” Joseph asks us to notice and appreciate.

Joseph is a creative writing teacher, editor, and manuscript coach in Ann Arbor. I interviewed her about Sparrows and Dust, her teaching, and what she’s working on next.

Detroit native and U-M grad Shannon McLeod’s new novella, "Whimsy," tells a different kind of teaching story

Shannon McLeod’s new novella, Whimsy, depicts the perils of those post-college, early career years through the main character for which the book is titled, Whimsy Quinn, who narrates in first person. McLeod is a Detroit native, University of Michigan graduate, and now high school teacher in Virginia.

Whimsy, who got her name because her parents wanted to name her something “that exuded light-heartedness,” works as a middle school teacher in Metro Detroit, copes with the aftermaths of a car accident that she was in, and navigates dating. She tells her story of how she weathers her setbacks, and it becomes clear how they strengthen her. When asked to describe teaching, for instance, Whimsy notes, “I told him I didn’t have much to compare it to, but that it seemed I had less free time and less money than people with other careers.” It is not a glowing description, but she also does not hate it.

Much of the novella situates Whimsy in the classroom. Her profession brings both humor and growth for her. Of running a classroom, she reflects, “I don’t know if you ever recover from the feeling of thirty pairs of eyes staring at you in concert.” That description may sound nightmarish to those of us who do not want to be the center of attention. Yet, Whimsy gets through the first few days of the school year and finds that the students’ levels of observation fade because by "Halloween you’re at the bottom of the students’ lists of interests.” A welcome change.

Teaching is fraught with challenges, though, from getting scolded by an administrator who questions Whimsy’s dedication to catching students passing notes in class, serving as a cafeteria monitor during lunchtime, and socializing with other teachers. Whimsy takes all these situations in stride. When she needs to be away from the classroom, she reveals, “I’d learned quickly not to expect my students to get anything done with a substitute teacher in the room.” A matter-of-fact and responsive character, Whimsy is well-suited to teaching even if she finds herself chagrined at times.

While Whimsy is a self-aware and descriptive narrator, the prose remains sharp and tight. Scenes unfold and shift. The reader sees along with Whimsy what’s really happening, such as at a wedding where Whimsy drinks too much. She attends it with a journalist, Rikesh, who she’s seeing. When she finds herself crying in the bathroom, Rikesh finds her, and Whimsy notes, “He said he would take me home.” Yet, the next sentence shows a different outcome because, she thinks, “I thought he meant he was coming home with me.” The chapter ends there. Disappointment is palpable but not explicitly stated. The endings of all the chapters are poignant, each like a short story coming to a conclusion.

I interviewed McLeod about her novella, participation with the Emerging Writers Workshops at the Ann Arbor District Library, the Wild Onion Novella Contest that Whimsy won, and what’s next.

Kirstin Valdez Quade’s novel "The Five Wounds" expands on her New Yorker-published short story

All of the characters in Kirstin Valdez Quade’s new book, The Five Wounds, are going through something major. While the challenges—teen pregnancy, addiction, cancer—are not uncommon, the ways that each generation of the family handles their circumstances drive the novel.

One character, Angel, has a son at age 15 and quickly becomes aware of how the adults around her do not actually have their lives together. Not only does she have that insight but she also must persevere when she doesn’t get the support that she needs and when she has to instead support the people who are supposed to be helping her.

Yet, Angel proves herself resilient, even from a young age. Her mother, Marissa, informs Angel:

“When you were three you said, ‘Mama, can you tell me all the things I don’t know?’ You were so impatient to learn and make your own way.

Angel smiles. “I don’t remember that.”

Knowing things does not comprise all of Angel’s learning, though. Along the way, she gains wisdom on what people are like and how to interact with them.

Her father, Amadeo, tries and tries to get his life together but keeps succumbing to alcoholism. He acts before he thinks. An accident caused by his carelessness and drinking miraculously results in only minor injuries, but it is the only thing that can convince him to get his life on track, not just for himself but for his family, especially as the whole family dynamic shifts when people enter and exit their lives.

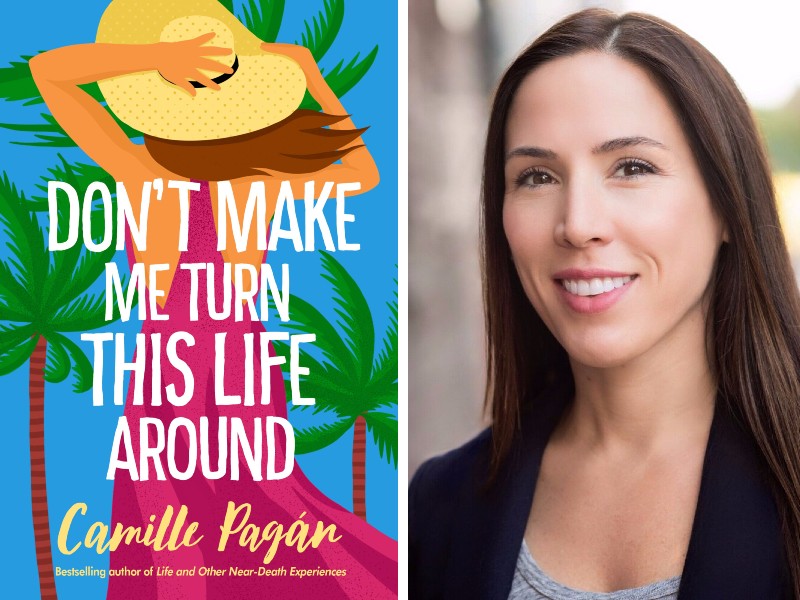

Camille Pagán's "Don’t Make Me Turn This Life Around" was partly inspired by the Ann Arbor author's disastrous vacation

During this cloistered pandemic year, lots of us have daydreamed about escaping to sunny, tropical destinations.

So readers drawn to the beach-y cover of Ann Arbor-based novelist Camille Pagán's latest release, Don’t Make Me Turn This Life Around, may be initially surprised to find that the book tells the story of a family getaway to Puerto Rico that goes very, very wrong.

But let’s keep in mind the time in which it was born.

“It’s my pandemic book,” says Pagán, and it follows up on the characters from her Amazon bestseller Life and Other Near Death Experiences but can also stand on its own. “It took me a while to get excited about it. … But I knew I wasn’t done with Libby. She’s my favorite of any of the characters I’ve created.”

U-M Librarian and AADL Board Member Jamie Vander Broek discusses libraries and "Radical Humility"

How do libraries and the quality of humility go together?

Really well, it turns out.

Jamie Vander Broek unveils this connection in her essay, “A Library Is for You” in Radical Humility, a recent book she co-edited with Rebekah Modrak, a professor in the Stamps School of Art and Design at the University of Michigan.

The Librarian for Art and Design at the University of Michigan Library, Vander Broek outlines how the permission to read whatever you’d like contributes to the humble nature of libraries. In contrast to museums, the people are primary:

Libraries, instead, devote relatively little real estate and resources toward interpreting their collections, instead foregrounding the individual’s experience with the materials. Another person’s ego doesn’t stand in the way of your access to, at our library, a letter handwritten by Galileo and the first cookbook published by an African American. That’s how important you are to us.

Libraries, Vander Broek observes, don’t impose themselves on one’s intellectual adventure or entertainment but rather offer their collections up to people who want to interact with them. There are many ways Vander Broek illustrates this humility, such as noting, “We think of libraries as being about books or even literacy. But they’re really about sharing. They’re about recognizing the value of saving, sharing, and access to society.”

Sharing is caring, many of us have learned from a young age.

Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle Marks National Poetry Month with a Reading and Open Mic

April marks the 25th year of National Poetry Month and Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle will mark the tradition during their monthly reading on April 28 at 7 pm via Zoom (email cwpoetrycircle@gmail.com for the Zoom link).

Poets Shutta Crum, Dana Dever, David Jibson, Joseph Kelty, Loraine Lamey, Gregory Mahr, Edward Morin, and Lissa Perrin will read. An open mic will follow and participants may read their own poem or a favorite poem by another poet.

The Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle has become a home for writers in the greater Ann Arbor area and has been meeting at the Crazy Wisdom Bookstore and Tea Room for about 10 years. The Poetry Circle offers workshops on the second Wednesday of the month and readings on the fourth Wednesday of most months. Currently, several poets, including Jibson, Morin, and Perrin, co-host the group.

Morin is the author of a recent poetry collection, The Bold News of Birdcalls, and gains inspiration from the monthly readings.

Beyond the Birds: Ann Arbor Poet Ed Morin’s "The Bold News of Birdcalls" explores nature, relationships, and work

The Bold News of Birdcalls by Ed Morin is not just about birds. Stories about people, relationships, work, and news occupy his poems. In “Moments Musicaux,” with a dedication to “my sister Audrey,” we read about her birth, marriages, and children. We learn that “Her last words to me were, ‘You’ll look younger if you get your hair cut more often.’ ” Morin sees both the gravity and the humor in his subjects.

Morin’s poems that do focus on nature or birds are not without the poet’s opinion. The poem “Icicles” says, “February is a sallow miser who hoards / what little daylight is left in the world.” Yet the collection is also not without appreciation for the natural world. We see how industrious birds can be, as “Housing for Wrens” offers the lines “along comes the plain-brown-wrappered wren, focused as a meter reader, from yard / to yard appraising birdhouses for nesting.” This poet not only observes the wren but also admits in another poem that:

Julie Babcock's poetry book "Rules for Rearrangement" considers how to carry on after a sudden loss

University of Michigan lecturer Julie Babcock’s recent poetry collection, Rules for Rearrangement, offers a journey to discover what those rules are. The book charts a thorough and far-reaching path through memories and ways to persist when someone has disappeared from one’s life.

The Ann Arbor poet writes, “Everyone is filled with a heavy combination / of blockage and sun.” The obstruction and brightness feel relatable. People have their burdens and their joys.

How might someone go about rearranging both what weighs them down and what buoys them? A stanza in a section called “Arson” asks for the following:

Introduce your new self and explain your need. For instance: I need rules for

rearrangement. For instance: I need to box memories. I need to let my

objects know it’s not them.

For Babcock, it can be a matter of space and objects. That same poem goes on to discuss how “Empty space you uncover will be awkward and shy.” Yet, “Former free space you cover will be angry.” This negotiation illuminates the effort it takes to design spaces, things, and even life differently than what they were before. The poet both rails against and is curious about the things around them and what happens to them.

At the end of the collection when “He returns from the dead so they can discuss Bob Dylan who won the Nobel / prize for literature,” it becomes clear that the rules may be malleable and dependent on how someone approaches them because "'My love,' he says, 'nothing is every one thing.'" Allowing for this multiplicity offers permission for whatever way a person moves forward in the wake of a traumatic event.

I interviewed Babcock about her new book, writing, and novel in the works.

Ann Arbor poet David Jibson on Crazy Wisdom's Poetry Circle, "3rd Wednesday Magazine," and his new book, "Protective Coloration"

It’s well-known that the life of a poet often means being attentive to the world around oneself, seeing parallels between things or living beings and their thoughts, actions, ideas, and values. David Jibson, co-host of the Crazy Wisdom Poetry Circle, uncovers these connections throughout the poems in his latest book, Protective Coloration.

The collection’s title is made clear by the poem of the same name, in which a restaurant scene unfolds "with the poet of a certain age, hidden in a corner booth / at the back of the cafe, as quiet as any snowshoe hare, / as still as a heron among the reeds.” There, we see the poet blending in while also taking in the view. Jibson welcomes the reader to join him in seeing striking insights through straightforward language, like the person in “Amy’s Diner” who, while studying the group of men in baseball caps eating the senior special, gets the invitation to “Pull up a chair.”

As people in another poem speculate while preparing and waiting for the arrival of guests, they are “as ready as we’ll ever be, / realizing, now, how much time has passed / since we last dusted in the corners of our lives.” The poems encourage readers to wonder at such things in their own lives.