UMMA's "Beyond Borders: Global Africa" asks what it means to be an artist from the continent

UMMA’s exhibition Beyond Borders: Global Africa extends a conversation recently addressed in Unrecorded: Reimagining Artist Identities in Africa. The newer exhibit asks the audience to consider the roles of contemporary artists, as the subtitle Global Africa suggests, along with a reconceptualization of previously narrow definitions of “African art” or “African artists.” UMMA director Christina Olsen states that the pieces on display, many of which belong to UMMA, “ask questions about what it means to be an ‘African’ artist and make ‘African’ art.” Included in the show are photographs, paintings, installations, and sculptures. This exhibition includes “approximately 40 works of art drawn from UMMA's African art collection and from private and public holdings around the world, including the eminent Contemporary African Art Collection assembled by Jean Pigozzi of Geneva, Switzerland.”

Along with the primary concern addressed in the exhibition, the conceptualization of borders, particularly in relation to the continent of Africa and its history, the exhibition also explores “issues such as slavery, colonization, migration, racism and identity through works by Kudzanai Chiurai, Omar Victor Diop, Seydou Keïta, Houston Maludi, Nandipha Mntambo, Fabrice Monteiro, Wangechi Mutu, Sam Nhlengethwa, Serge Alain Nitegeka, Alison Saar, Chéri Samba, Kehinde Wiley, and a host of unrecorded artists.”

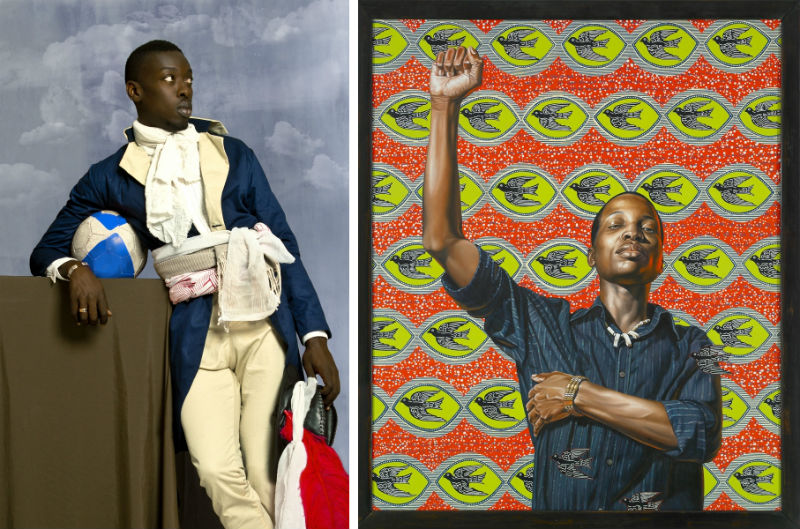

Photography plays a prominent role in the exhibition. Immediately upon walking into the gallery, the work of Omar Victor Diop is visible and eye-catching. His play on 19th-century portraiture is evident in his stylistic choices, in addition to the styling of the subjects. His photographs resemble traditional paintings, drenched in highly saturated colors. The first piece, Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) from Project Diaspora: Self Portraits, is based on the iconic daguerreotype of Douglass taken in the middle of the 19th century. Diop “alludes to his reputation as a skilled orator by holding a whistle, drawing a parallel between sound and voice. The whistle is also a reference to the world of soccer, a wildly popular sport in Africa and Europe.” In another work by Diop, Jean-Baptiste Belley (1746-1805), also from Project Diaspora: Self Portraits, the referents to soccer become more obvious, with a ball replacing the classical bust that can be seen in the original 1797 painting of Jean-Baptiste Belley, a key figure working toward the abolition of slavery in the French colonies.

Fabrice Monteiro’s photographic work is a great example of the integration of complex histories mediated by an influx of people across permeable and shifting borders. Monteiro lives and works in Senegal, and addresses “Afro-European encounters in Senegal” in his photography. His Signares series is a reflection on late-18th- and 19th-century commerce in Senegal. Local women would enter into temporary marriages with European sailors, merchants, and sailors. These colorful photographs show women in period dress worn by historical signares and show a blend of European and African fashions “suggesting that they successfully navigated both realms.” Like Diop, Monteiro works with highly saturated colors and references traditional portrait-studio settings. This tension between history and contemporaneity is another central theme of the works in this show.

Many other artists engage with specific historical moments or art movements of the past, such as Tribute to Romare Bearden from Tribute Series by Sam Nhlengethwa. This tribute offers homage to the work of mid-19th-century artist Romare Bearden, an African-American artist most known for his collage work. The color lithograph shows an interior domestic scene in which, presumably, Bearden’s collages decorate the walls. By taking a well-known and influential African-American artist’s work and including it in this tribute leave the viewer to consider the impact of collecting on the trajectory of art history. This is particularly relevant when considering the broader scope of the exhibition. The gallery also features a tribute to David Goldblatt, the wall text accompanying it suggesting that Nhlengethwa “honors the colleagues, past and present, who have influenced his artistic practice and paved the way for him and other artists.”

The exhibition also includes two paintings by world-renowned artist Kehinde Wiley. Known for his photo-realistic style and vibrantly patterned backdrops, Wiley uses conventions of “European Old Master portraits.” Wiley then chooses a subject, often a random passerby from the street, to stand in front of the backdrop and pose. Wiley’s subjects often take on the pose of a traditional portrait, with contemporary objects and clothing. Thus, he “inserts historically underrepresented people into dominant cultural narratives.”

The curators note throughout the space that they work within is a set of constructs that do not always reflect the reality of lives lived. Curator Laura De Becker writes on the subject: “Many of the countries we know on the continent today were created in the late 19th century when Africa was carved up by European colonizers. … Colonial borders also failed to acknowledge that people, ideas, and goods in Africa have always been mobile. Indeed, the continent’s history is defined by encounter and exchange, with its arts at the very heart of these interactions.”

With the utilization both contemporary and historical works by artists not only from Africa but from Europe and the United States, De Becker hopes to question what it means to make "African" art in the era of globalization.

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

"Beyond Borders: Global Africa" is on view at the University Michigan Museum of Art to November 25. Laura De Becker, UMMA’s Helmut and Candis Stern Associate Curator of African Art, curated the exhibition.