Jimi Hendrix's Experience: Jas Obrecht's "Stone Free" goes deep into the guitar great's transformative 10 months in London

This story originally ran February 11, 2019.

The life of guitar legend Jimi Hendrix has been explored in numerous biographies and documentaries, so you could be forgiven for being skeptical as to why the world needs another book about the man widely considered to be the greatest guitarist of all time and a major influence on the sound of rock music. Jas Obrecht's new offering on the subject, however, takes a much closer look at a specific period in the life of Hendrix.

Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London, September 1966-June 1967 is a detailed, day by day look into the guitar great's arrival in England and his rapid rise from obscurity to fame. Obrecht's book puts into perspective just how quickly and completely Hendrix revolutionized pop music. The supporting cast is a who's who of British rock icons including The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, The Who, The Animals, and many others. I had the pleasure of sitting down for an interview with the author, who has written nearly 200 cover stories for Guitar Player and other music magazines as well as a number of books on blues and rock.

Obrecht will be reading from his new book on Thursday, February 14, 7 pm, at Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor. Below is the conversation we had, slightly edited for flow.

Q: What was the impetus for writing this book?

A: In 1995, on the 25th anniversary of Jimi's death, I was in my office at Guitar Player Magazine and the phone rang and this voice says, “Hi, this is Jimi Hendrix's sister Janie, and my Dad wants to know if you'll write a book with him because he wants to get the story of Jimi's life straightened out before he dies.” So I flew out to Seattle and I met with [James Albert Hendrix aka Al] and we hit it off and I decided I would co-author this book [My Son Jimi] with him. But I always felt like that was Al's version of the story, and for me, the most interesting part of the Hendrix story is what happens when he's away from Seattle and goes to London. But what made writing about that so difficult was that there wasn't much material around. In the days before the internet, you couldn't find the interviews Jimi did in London or the coverage he got when he toured France or played in Scandinavia. But I started exploring and finding all this material getting posted online, and I thought, “The time is right. Someone's going to do this and do it right, so I'm going to take this on.”

Q: So before this book, there was not a detailed history of Hendrix's time in England?

A: No. There were these big biographies that covered his whole life, but having the insight into his life that I did through hearing all of his father's stories and family history, I thought, “Why not write a Hendrix book with a happy ending?” So, I'll start with him leaving to go to London as this unknown guy who's perpetually broke and freezing in the cold with threadbare clothing and holes in his shoes, and then he steps off the stage at Monterey nine months later, the biggest thing in American rock-n-roll. I thought, “That's a remarkable story. A book like that would really resonate with people and it would allow me to draw all of these disparate sources together.” So, to construct the book, first I found all of the Hendrix quotes I could from that period and flew them in. Then I looked at Noel Redding's, Mitch Mitchell's and Kathy Etchingham's memoirs [Etchingham was Hendrix's girlfriend during this time]. And I had interviewed a lot of people who knew Hendrix during my 20 years at Guitar Player Magazine. That gave me the skeleton of the whole book. Then I started finding all the different studio takes and club gig recordings online, and videos and things like that. So I was able to assemble more than 150 different recordings of Jimi during that nine-month period. I put it all together, and then for me, the best part was at the end, after I put in all the biographical material and the discographical information, then comes the fun part, which is me watching him on video or listening to him on the stereo. I was able to watch him play and suss out techniques. I've always been good at hearing parts on a recording and figuring out how it was done, or how they set up in the studio.

There are a lot of quotes in this book, and most of them are from the late '60s. Much of the book is in the words of people who were there with Jimi at the time.

I was well aware that every Hendrixophile on the globe would be looking at each sentence in this book with an electron microscope. I knew that before I started. Having written about blues all my life, I know that some members of the blues audience can be difficult and critical. If you misspell a name in a caption, you'll hear more about that than the rest of the book. And I knew that with Hendrix it would be just as bad, so wherever I could I quoted people exactly the way they said it and left it intact. With My Son Jimi, it was all Al's words and I figured, anyone who wants to argue with it is going to argue with the man who was actually in the room. That takes the pressure off of a writer in a certain way. So if you want to argue with Kathy Etchingham or what she says in the book, that's fine, but you're going to get what she said because she was there.

Q: Did you do any new interviews?

A: I didn't, for a very specific reason. Very early on I started watching YouTube videos of people like Clapton and other people who knew Jimi, talking about him in the modern era, but then when I found the sources from 1966 and 1967 they were saying and describing things differently. People change the story to make it more entertaining. If you tell the same anecdote 50 times you've got it all polished up, but the first time you tell that story it's probably closer to the truth. So that's what I went for.

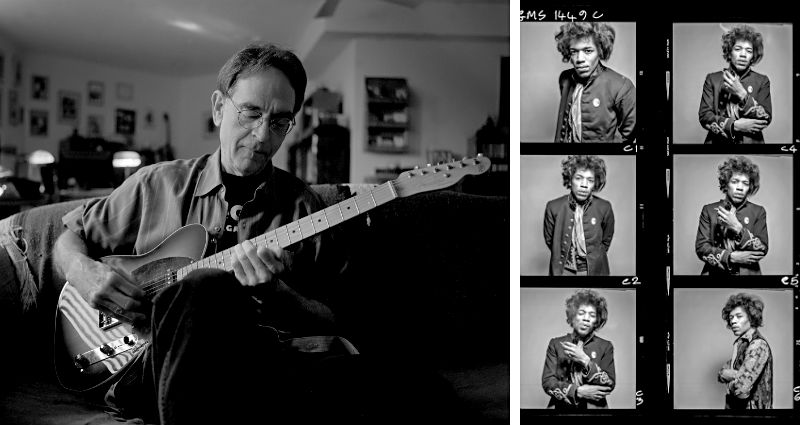

Q: But you did interview local guitar legend Brian Delaney.

A: That was interesting. I met Brian through my friend Mike Gentry. I needed more information about the way Jimi played. So I went over to Delaney's house one snowy day, and it was amazing. I brought over the Hendrix recordings that I had questions about and he put them on the stereo and then he went over and duplicated every single sound, on the spot. It was quite remarkable. So I thought, I'm going to let him explain this and give him some ink. He's sharp. I'm a big fan of his mind. Superlative player, too.

Q: I noticed that you didn't shy away from including some of the racist language that was used to describe Jimi. Not just by the press, but even in a passage from Clapton where he uses the word “spade.”

A: Isn't that shocking? The racism was way more pervasive than I imagined it would have been in England. What I found most interesting about all that is Hendrix's reaction. He took the high road. He didn't condemn anyone. He didn't play it up in interviews. He didn't show a reaction of being upset by it. He said, “If it comes out of ignorance, that's one thing, but if it's malicious, then I have a problem with it.” I found it fascinating that Jimi just didn't take the bait. He had a mission. His mission was, “I'm going to create this music, I finally have a chance for the first time in my life to do this, and I'm not going to let anything get in the way.” You have to say no to everything that gets in the way of being creative. I tell that to writing students all the time. You have to block out time and turn off all distractions. It would have been easy for Hendrix, I think, to get distracted or depressed by the racism that he encountered, but he just powered on. He had a great strength of character. When I went into the project I was kind of nervous because sometimes you get a book on someone you admire, and you read it and you go, “Oh, man, I wish I didn't know that about him. I didn't want to know this.” But with Jimi, except for the one incident where he punches a girl, I liked everything I learned. He turned out to be more creative and charming and brilliant than I had ever thought. What blew my mind the most was his ability to write so many songs in a six or eight week period. Unbelievable. There's never been a run like that that I can think of, ever. It was a stunning achievement. And it happened before the drugs and the hangers-on kick in, which was immediately after Monterey. He was never that productive again. Although Electric Ladyland is a superior album, that period between December and February where suddenly they're copyrighting everything on the first album and a lot from the second, is just stunning. What discipline. I mean, he shows up in England and seven days later he's head-cutting Clapton on stage with Cream. What else can you say? And here we are 50 years later, still blown away by it.

Q: Right. Which brings me to the question: Why is Hendrix still relevant? It's been over 50 years since the events in this book transpired.

A: Hendrix is a great example of the embodiment of creativity, sensitivity, and open-mindedness. And then there's just the playing. The playing is astonishing, to this day. Hendrix still sounds fresh and original. He's doing things that people still don't do, or when they imitate it, it doesn't come off nearly as interesting. He's like a Bob Marley, a Louis Armstrong, a Miles Davis, Blind Willie Johnson, these people who are unique and unsurpassed in what they do and continue to influence decades and decades after they're gone. He's like a Coltrane of the guitar. But he wasn't just a guitar player. He was an interesting character as a singer, as a fashion icon, as someone who is an African-American man going into rock music and getting huge, I mean, that was unheard of.

Q: Who is the audience for Stone Free? Who should read this book?

A: I didn't want it to be just for gearheads and guitar players. I wanted it to appeal to people who like fiction, like a good novel. Every night when I was working on this book, I would read Mark Twain. I would read a chapter or two of Tom Sawyer or Huck Finn, because those are fantastic novels that have a beautiful arc to them, and they are actually a series of anecdotes that are strung together in a way that makes them really interesting and show the growth of the characters. And I thought, I'm going to do the same thing with Jimi, telling one great story after another. You know, he gets off a plane and goes to a house, and these people see him play, and Kathy Etchingham is upstairs, and then he goes to a club and he plays, and people see this, and then a fight breaks out, and so on. So I really owe a nod of appreciation to Twain's works because that was my biggest influence with writing this book.

Q: Is that something that you typically do?

A: Well, I've been teaching creative writing at [Washtenaw Community College] for almost 20 years, and I've always thought that the best novels are the ones that have these beautiful anecdotes that just go one into another and another, and you can take any of them separately and they each stand alone. So I was hoping that with every two-page spread I would be able to get into something really interesting that even the most devoted Hendrixophiles may not have heard about.

Q: I was really amazed by the pace of the Experience's work life. Once the band was put together, every day was a gig, recording session, or interview. They seemed not to have any time off.

A: This gets into the stressful area. This is what kills Jimi, ultimately. Mike Jeffery does not give him a break. People around Hendrix near the end said, “This guy's really super-depressed. He needs to get away, he needs six months off,” and Jeffery wanted nothing to do with it. He kept pushing him to do one gig after another and it burned him out and killed him. In my opinion, that's what caused Jimi's death. As an artist, you need downtime. You need to decompress, you need a chance to be creative. You need a chance to think, away from your instrument, from the crowds, to replenish what's inside of you. It's remarkable how much they worked him, and how little they shared the money with him.

Q: This book references so many videos and recordings. A person could spend many hours listening to and watching live recordings from this time period. What is one that you recommend most highly?

A: There's one I talk about in the book where he's on the German show Beat Beat Beat. It's easy to find this black and white footage of him, and it's beautifully photographed. The cinematography is great. You can actually see his hands, his teeth, and that just opens up a whole world of information on how he played and his technique.

Q: You took some time at the beginning of the book to connect Hendrix to his musical roots.

A: Oh, you have to, because they were on full display when he got to England. In England, they'd been hearing this on the record or maybe they had seen the watered down show band version of it, but Hendrix, to the Brits, was the real thing. He was a guy with the credentials of having played the blues on the Chitlin' Circuit. It was like the real thing had arrived. It was very similar to when Big Bill Broonzy and Muddy Waters came over in the 1950s and blew them away. Hendrix did the same thing, only he had more on the table than those guys. He was young, he was good looking, he was a total magnet sexually speaking. It was just the complete package. Take a player like Stevie Ray Vaughan, who I greatly admire. When I listen to Stevie, I can say, “Now he's going into Chuck Berry, now he's going into Jimi Hendrix, now he's doing Albert King. Now he's doing Larry Davis, Texas Flood.” With Hendrix, you don't do that. You listen to Hendrix doing something simple, like "Johnny B. Goode," and he takes it off into outer space. He does things that Chuck Berry couldn't possibly have imagined. And if you think about the journey of the guitar, there's only 12 years separating "Johnny B. Goode" and Hendrix at Woodstock. Look at how the guitar changed in 12 years, from 'Johnny B. Goode' with a piano and a standup bass in the background to the Star Spangled Banner at Woodstock. It's an incredible acceleration of an instrument, and Hendrix was right there in the middle of it, right there doing it. I still think that the "Star Spangled Banner" is the most transcendent piece of music from the 1960s. It says it all. As an anti-war protester, that really resonated with me. You could hear the bombs. Jimi was fearless!

Alex Anest is an Ann Arbor-based guitarist. He spends his time playing music with friends and teaching other people to do the same. You can find more of his writing at anestmusic.com.

Jas Obrecht will read from "Stone Free" on Thursday, February 14, 7 pm at Literati Bookstore in Ann Arbor. You can read an excerpt of the book here: "London Bridge: A remarkable inside look at Jimi Hendrix's rise from obscurity to international fame." [Guitar Player, Nov. 28, 2018]. Read our previous interview with Obrecht: "String Theory: Jas Obercht is "Talking Guitar" at Nicola's Books" [May 11, 2017].