Lyrical Lines: “Matisse Drawings: Curated by Ellsworth Kelly" at UMMA

Matisse Drawings: Curated by Ellsworth Kelly at the University of Michigan Museum of Art’s spacious second-story A. Alfred Taubman Gallery is proof that less is more when it comes to art.

Principally managed by the UMMA’s Assistant Curator for Western Art, Lehti Mairike Keelmann -- herself working from the late-Ellsworth Kelly’s instructions -- this exhibit of 45 Matisse drawings (with an additional nine Kelly lithographs) from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation Collection cuts an artful swath across this French master’s career.

“This exhibit reflects the imaginative artistic rapport of two celebrated artists through lyrical line and efficiency of gesture," Keelmann said in a recent interview. "But how they get to the place where they intersect is the subtle underpinning of this deceptively complex exhibition.”

Both artists are noted for colorful approaches to painting, Keelmann said, "Yet Matisse favors a refined reduction of line in these drawings; while Kelly favors a further economy of line in his prints. These facts alone make this exhibit a unique study of comparison and contrast. Kelly obviously admired Matisse’s ability to make every mark of his drawings uniquely his own. And he was inspired by Matisse’s handling of his line; as Matisse’s drawing is largely simple and always thoughtful. Yet there’s also a close engagement between Matisse and Kelly’s gesture. What Kelly finds in this concise artistry, through both curatorship and art form, is what he chooses to emulate in his own manner.”

It’s these clues that unlock the delicate symmetry in Kelly’s arrangement of Matisse Drawings.

Matisse (1869-1954) defined many of the last century’s visual arts developments through his explorations in painting, drawing, papier collé, and sculpture. He was, paradoxically, both a modernist innovator and champion of the classical French tradition through his mastery of expressive color, with precise yet abstracted articulation in multiple mediums, creating a spectacular body of work that spanned over a half-century. His drawings in this exhibit illustrate Matisse’s varied artful interests.

Kelly said Matisse’s drawings exemplify the unique ability of genius to bend and subordinate draftsmanship to the point of an unmistakable signature. The single most remarkable effect of Matisse Drawings is to witness a line that is singularly expressive and singularly inimitable. In fact, it’s difficult to fully appreciate Matisse’s accomplishment without actually seeing the tactile application of his pen or pencil to paper.

Granted, it would be impossible to know to what extent Matisse may have failed in his application of line throughout his career because we cannot gauge what we cannot see. We can only see what Ellsworth has chosen to display in this exhibit. Yet given the richness of this art, there’s plenty of indication that Matisse succeeded in his self-appointed task far more often than he failed. One hint is that there’s little false marking in Matisse’s drawing. The line -- whether vertical, perpendicular, or curvilinear; thick, thin, near-translucent, or otherwise -- is almost always markedly assured.

For example, the gentle nape of his model’s neck in contrast to her folded arms in an undated ink on paper titled Nude With a Bracelet is but one example of Matisse’s ability to give character to near-abstracted form. Just as 1935’s pencil on paper Woman Leaning finds him masterfully controlling his line through another such classic nude study.

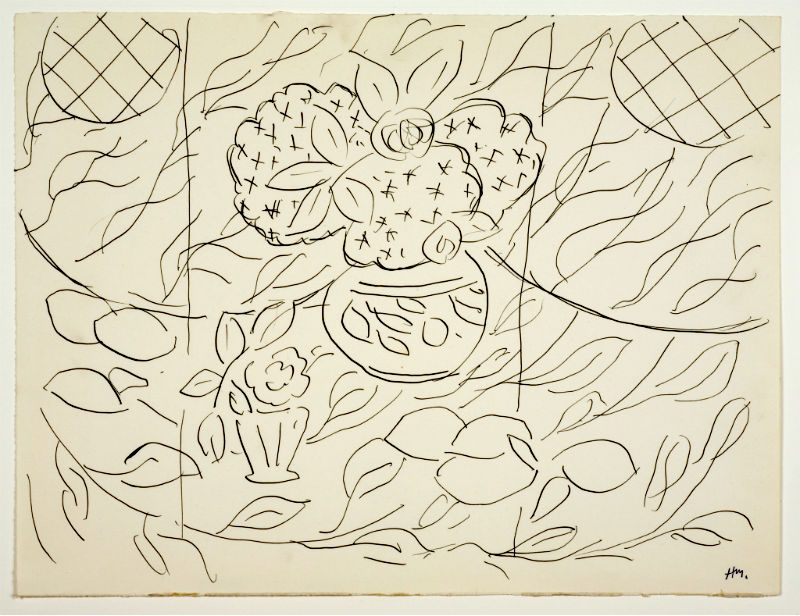

Of the many other works in the exhibit, Matisse’s 1944 ink on paper Sketch for the Painting "Lemons and Mimosas on Black Background" is remarkably powerful. The absence of his always vibrant color essentially creates the context of color as intricate waves of cross-hatched mimosa leaves and decorative lemons loosely inspired by 19th-century French Chinoiserie painting are abetted by two flattened vases, which both feature the suggestion of equally accomplished outgrowth of flowers. Matisse’s crafting of this intricately complicated still-life remains buoyantly balanced through his seemingly effortless articulation of intangible space.

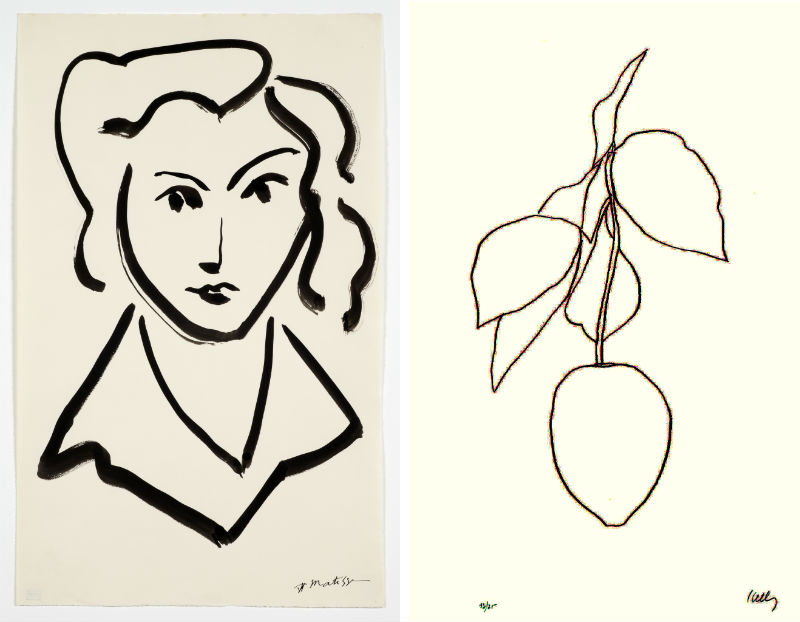

Likewise, the undated ink on paper Head of a Woman is accomplished through an inspired sleight of hand. Really no more than a series of thickened curvilinear lines, each expression is infused with extraordinary character, the whole being far more than its bountiful parts. There’s plenty of brilliant Matisse available to champion in this display, but Head of a Woman isn’t a bad place to start.

So what does Kelly (1923-2015) bring to the proceedings other than his curatorial skill in his part of the exhibit entitled Plant Lithographs by Ellsworth Kelly, 1964-66?

For starters, he’s keenly enthralled by Matisse’s aesthetic. But all modesty aside, his career is quite accomplished as well. As he’s quoted by Keelman from her gallery statement on the Taubman Gallery wall, “You must not copy nature. You must let nature instruct you and then let the eye and the hand collaborate.” Matisse couldn’t have said it better.

Kelly -- a mid-20th-century American second-generation Abstract Expressionist -- crafted a distinctive minimalist hard-edge Color Field-style of painting whose intense pigment and absolute line is as unmistakable in its way as Matisse’s art. Indeed, an examination of Kelly's nine lithographs in this exhibit shows us what it was about Matisse that gained his attention and liberated his own approach to drawing.

In a 2014 interview conducted by John R. Stomberg, the director of Dartmouth College’s Hood Museum of Art, Kelly said, “A lot of people have said, ‘I always thought your drawings look like Matisse.’ But they don’t. My drawings are very American. Matisse evoked space. For instance, when he would do leaves or fruit or still-life, he would leave openings. Like this would be a leaf [gestures a vaguely C shape in the air]. But my drawings are about shapes; the forms are closed.”

And right they are.

As a single example, Kelly’s Lemon (Citron), a 1965-66 lithograph on Rives BFK paper, exhibits a precise design that hovers majestically on his working surface. And he’s certainly correct in his aside to Stomberg: There’s next to little of the Matisse work in this show that comes close to the measured articulation of Kelly’s line.

The fruit he crafts in Lemon (Citron) is most definitely closed. Yet it also yields a superb volume of space in what is a flattened outline. One can imagine Matisse nodding in approval, but Kelly’s exact touch also creates a magnitude that suggests the minimal color of his painting. In fact, it would have been interesting to see what palette he might have applied to the drawing.

But this consideration is, admittedly, well beyond the scope of this exhibit -- better to leave well enough alone. And as such, there’s no other succinct way of expressing Kelly’s effort of mirroring Matisse other than that supplied by Keelman in her concluding remark about both parts of the exhibit:

“Whether Kelly or Matisse, deliberation is the order of this display.”

John Carlos Cantú has written on our community's visual arts in a number of different periodicals.

Matisse Drawings: Curated by Ellsworth Kelly from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation Collection runs through Feb. 18 at the University of Michigan Museum of Art, 525 S. State St. The museum is open Tuesday-Saturday, 11 am–5 pm, and Sunday, 12–5 pm. For information, call 734-764.0395 or visit umma.umich.edu.