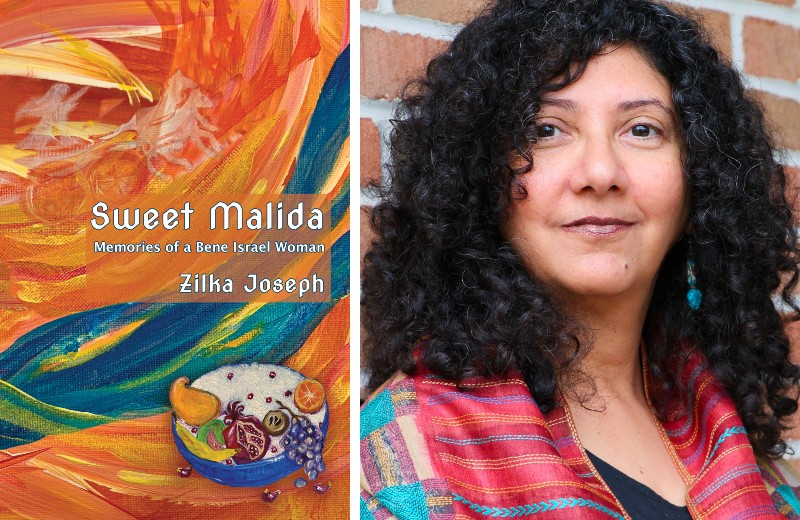

Poet Zilka Joseph imparts memories, history, and culture of the Bene Israel people by way of food in “Sweet Malida”

“From tumbled sands and shattered bark / blurred shadows dragged us,” writes Zilka Joseph in her new poetry collection, Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman.

These poems are immersed in the history, customs, and food of the Bene Israel people. The Ann Arbor poet shares about their shipwreck on the shores of India, worship of the prophet Elijah, and subsequent dispersing across the world. While Joseph imparts facts about the culture and community, she also makes the poems personal with her memories.

This cultural and familial history informs Joseph’s poems, such as “Leaf Boat,” which is a longer poem that receives its own section of the book. Joseph describes “my body a leaf boat / lamp floated on water” in the context of the heritage of her ancestors, grandmother, parents, and herself who moved from place to place. Even her birth was during unsettled weather: “I was born Thursday in monsoon rain / night time East coast time / in Bombay a baby opens her eyes.” Water, especially oceans, flows through the lines, and “in my dream / the whales are singing.”

Joseph focuses less on what is lost, though she does pay tribute to her parents, and focuses more on the richness that the traditions and foods of the Bene Israel pass along. One such food is “draksha-cha sharbath. Sherbet of raisins” for Shabbath, which Joseph writes about replicating on her own after moving to the United States. Earlier, she had prepared it with her grandmother and mother. As she writes in one of the short essays or prose poems that are interspersed throughout the book, making this recipe is like time traveling for Joseph:

Soon enough, it is time to strain the almost purple liquid, smash the pulp and squeeze the last drops of juice out. And make sure no seeds escaped. Now, again, I think of the figure of Autumn in Keats’ poem, slow and almost intoxicated with the fumes emanating from the apples being pressed. The juice oozing, her eyes drooping. Her mind lost in dreams. I become this sleepy, dreamy girl. When I open my eyes I can’t see the people I know. The scenes around me have changed too.

One whiff brings to mind all of these individual moments in time.

In fact, Joseph knows her religion and culture through food. Praises of Elijah are paired with “the nutmeg, the cardamom, the freshly / sliced mangoes, guava, chikoo, apples and / bananas arranged like garlands.” The book itself is named after a dish for Shabbath: “Sweet malida, / a mix of water-softened / flattened rice, sugar, / dried fruits and nuts….” This interest in food for Joseph stems from girlhood when she gorged on green curry, which she writes about in the poem “Green Kaanji and Destiny:”

(who could know what or who I would turn into

when I grew up and who knew

what “foodie” meant

did the word even exist then)

Whether or not there is a term, Joseph nevertheless found her path to food and sees how food invokes memories even in a “new land new life new history / food and ways you made your own.”

In our interview, Joseph and I talked about Sweet Malida, autobiographical poetry, and prose poems, and food.

Q: When we talked last, your chapbook called Sparrows and Dust had just been published. What has your life been like since then?

A: That same year (2021), my full-length collection called In Our Beautiful Bones was published. It was a finalist for the Forward INDIES Book Award. Unfortunately, due to COVID restrictions, I was unable to do events or travel to promote my book. I did some readings in Michigan and New York City much later. Mostly, I continue with coaching and helping writers perfect their work and manuscripts.

Q: Sweet Malida: Memories of a Bene Israel Woman is autobiographical. How did the poems merge into this collection?

A: This collection developed in a very organic way. I had several poems about food, food and childhood memories, some of which were published in RASA, an imprint of Whetstone Magazine. The title poem, “Sweet Malida” was published in an anthology called 101 Jewish Poems for the Third Millennium.

My collection is not just autobiographical, it focuses on the complex history of a micro-minority whose existence is hardly known or acknowledged, particularly in the West. There are poems that are about the arrival of my Jewish ancestors in India in approximately 175 B.C.E. They were shipwrecked close to the village of Alibaug. I imagine how they survived, and the ways they adapted to life on the West Coast, while still following the basic tenets of Judaism. I explored the myths around the Prophet Elijah, who is an important and dramatic figure in the Old Testament, and a significant figure for the Bene Israel, as he is said to have visited a village in the Western Ghats. What remains is a rock that is said to bear the marks of his chariot wheels. These are all fascinating stories, and many blended well with childhood memories of my mother and grandmother making special Bene Israel dishes, the journeys of my ancestors, my grandfather in Palestine and Egypt during World War I, my father and mother, as well as my own journey to the U.S.

Q: Relatedly, since the poems are called memories, the author appears to also be the speaker. What is different about writing poetry in which you are the poet, rather than the poet as its own voice?

A: The poet is the speaker in both cases, in the lyric poems and in the prose pieces. There is always a persona involved. In the short essays, I had to focus more on how I might behave or speak as a child. I can’t at the moment think of any other difference.

Q: For readers who are unfamiliar with what malida is, would you share about this food and ritual and why you wrote about it?

A: The poem “Sweet Malida” describes this very simple dish of flattened or parched rice which is rehydrated, mixed with sugar and ground coconut. Dry and fresh fruits are often added as well. For the more formal Malida ceremony, which is a thanksgiving celebration for Prophet Elijah, the malida is decorated with an abundance of local, seasonal fruits, and roses or rose petals are added for their fragrance. There is a prayer (barakha) that is said over the fruit of the vine, the fruits of a tree whose wood can be used to make a house, and the fruits of a tree that cannot be used to build things, as well as a prayer for flowers and fragrance. The decorated malida platter and these rituals are described in the first poem “Eliyahoo Hanabi” It is an invocation to Prophet Elijah, and the chant which is repeated in the song of praise.

Q: “The Laadu Makers” reads “So much is fading already, but the tastes never do.” Food is the integral thread that connects history, culture, and memories together in these poems. Tell us how you see food showing up in these poems and the various roles that it plays.

A: Food is very important to me. Not only because I love food and live to eat, but I am interested in food history and anthropology, food ways, culture, and cultural influences. Memories of my mother and grandmother become integral to this collection as they cook dishes that are special to my culture, and food connects us through these memories. The sensual imagery brings not just the food, but my lost loved ones back to life. In my previous book, In Our Beautiful Bones, I have several poems about food, hunger, and memory, and some have political subtexts.

Q: These poems tie together many references, from the Bene Israel in India to the biblical story of Elijah, who was fed by ravens. How did you balance these communities and customs with your personal and familial experiences as you wrote?

A: These are all part of me/who I am, my experiences, and my education, so they flow quite naturally into my writing. The short essay that opens the collection refers to my background and influences. I experiment with associations, images, myths, mysticism. The raven of Noah, the ravens of Elijah, manna from heaven, the crows that steal tidbits, the shipwreck, maritime images and metaphors, my marine engineer father’s stories of sailing, and my own story of migrating to the U.S. Forms in the book, too, vary, as they do in my previous books as well. Fragmented narratives, short essays, lyric poems, a sonnet, a pantoum—all play a role in this book.

Q: Prose poems are interspersed among the poems. Do you consider these as prose poems or short essays interspersed with your poems? When do you decide to write a prose poem or in verse? Why?

A: I don’t decide until I have spent some time working on what I have written (raw material) quite spontaneously, and I begin to give them shape. A lot of thought and craft goes into this shaping. Some pieces I write naturally become poems, and some just work well prose—short essays, short creative nonfiction—whatever you’d like to call them. Sometimes I have a poem that seems to need more story or description, and I may try it out as a prose piece. Sometimes it’s the other way around. A prose piece that is lyrical, has strong imagery, or is more elevated in tone may be honed down and become a poem. Sometimes it’s a hybrid form. All of these forms (and those that may not have names) express creativity and offer variety and elements of surprise.

Q: What are you reading and recommending this year?

A: An eye-opening and absolutely stunning memoir published a couple of years ago that I highly recommend to everyone is The Art of Leaving by Ayelet Tsabari, a Yemeni Jewish woman. Some great novels on my shelf waiting to be read are The East Indian by Brinda Charry, The Dream Builders by Oindrila Mukherjee, and The Covenant of Water by Abraham Verghese. For poetry, Ranjit Hoskote’s new book of poems, Icelight, and What to Count by Alise Alousi are exciting new collections.

Q: With six books of poetry published, what is next in your writing life?

A: I’m thrilled to say that Sweet Malida is my sixth collection. I can’t believe it sometimes. An international edition of my book will be published by Pippa Rann Books U.K. and Penguin Random House India in the fall. I am very dedicated to my art. This is my life. I want to keep writing and publishing high-quality as well as interesting/thought-provoking work. I hope my work will move a reader on a personal level, be memorable, informative, and perhaps in the long run, have some impact in the world of literature.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.

Related:

➥ "Ann Arbor writer Zilka Joseph shares two poems and an excerpt from her new book, 'In Our Beautiful Bones'" {Pulp, December 10, 2021]

➥ "Zilka Joseph’s new chapbook, 'Sparrows and Dust,' finds parallels between humans and birds" [Pulp, July 12, 2021]

➥ "Zilka Joseph on Michigan poets and her favorite Ann Arbor literary haunts" [Pulp, September 7, 2019]

➥ "Review: Zilka Joseph Poetry at Ann Arbor Book Festival" [Pulp, June 30, 2016]

Comments

Zilka, What a wonderful…

Zilka,

What a wonderful piece of insight into what you do and who you are. I'm very interested in your Bene Israel connection. My husband's father comes from a cultural Jewish tradition which makes me interested in those intersections. Also my daughter just married Donald Harrison whose father is culturally Jewish, another connection. And Jeanne and Donald will be having a baby due on June 20!

I'm still writing poetry and reconnecting all these interconnected family stories.

All my best wishes,

Margaret Parker