“No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography at U-M's Clements Library

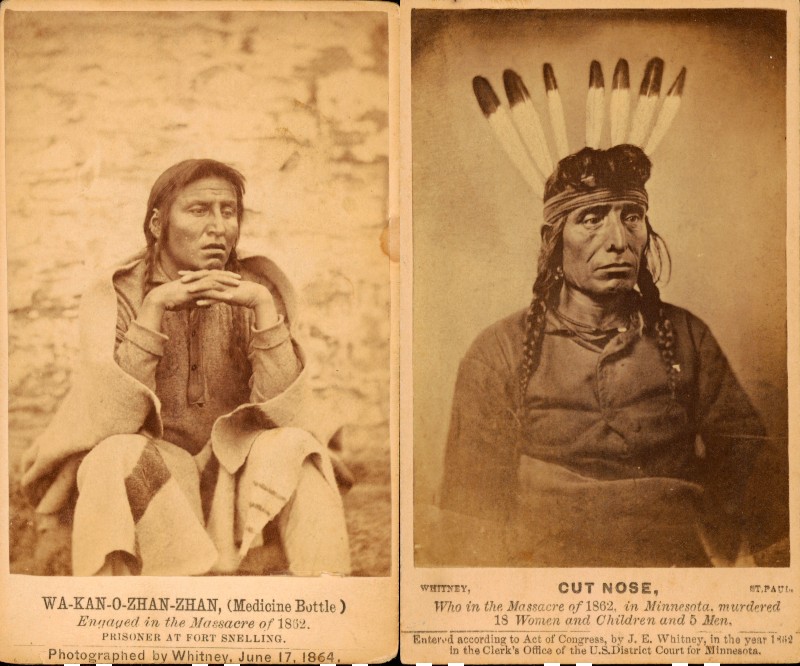

Joel E. Whitney

Carte de visite, 1864

Wa-Kan-O-Zhan-Zhan, or Medicine Bottle, was a Sioux wicasa wakan, or holy man, who stepped away from that role to defend the Dakota way of life in the rebellions. After the uprising, Congress called for the removal of all Sioux from Minnesota, leading Medicine Bottle to flee to Canada. Two years later, he was found, drugged, and brought as a prisoner to Fort Snelling, Minnesota, where he was tried for his participation in the 1862 uprisings. He was executed three years after the initial trial. This photo was taken shortly before his death.

Joel E. Whitney

Carte de visite, 1862

Marpoya Okinajin (pronounced: Mar-piy-a O-kin-a-jin) was also known as Cut Nose or He Who Stands in the Clouds. His vibrant life was filled with stories of hunting, fighting, and womanizing. Cut Nose’s distinctive name is credited to John Other Day, who allegedly bit off a chunk of his nose during a fight. During the Dakota War, Cut Nose fought to restore Santee Dakota sovereignty in Minnesota and is remembered for his leadership and brutality in the uprisings at Fort Ridgely, Minnesota. He was ultimately executed for his violence against settlers on December 26, 1862. After his death, William Mayo, a founder of the Mayo Clinic, exhumed Cut Nose’s remains to use for science experiments, keeping his bones for over a century and a half. The eagle feathers appearing in this photo were likely retouched into the photo after it was taken.

This review was originally published December 3, 2020; after the jump, we've included a video interview with the curators published on AADL.tv on November 15, 2021 as part of 30 Days of National Native American Heritage Month.

As I look out over a pond that's rippling gently from snowfall, the pine trees and fields covered in white, I'm writing this post in my Christmas-light-bright house, which rests on Bodéwadmiké (Potawatomi) land ceded in a coercive treaty.

A version of the above sentence is also what begins “No, not even for a picture”: Re-examining the Native Midwest and Tribes’ Relations to the History of Photography, an online exhibition produced by two University of Michigan students with Native American ancestry for the William L. Clements Library. Lindsey Willow Smith (undergraduate, History and Museum Studies; member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians) and Veronica Cook Williamson (Ph.D. candidate, Germanic Languages and Literatures and Museum Studies; Choctaw ancestry, citizen of the Chickasaw Nation) used materials in the Richard Pohrt Jr. Collection of Native American Photography to explore ideas of consent, agency, and representation.

“No, not even for a picture” feels succinct in its presentation—there are around 50 photos and documents—but its impact was enormous on me. I think it's because I've felt a combination of increased empathy and anger during a year that's been an unmitigated disaster for nearly all but the wealthiest Americans, with minorities, including Native Americans, being hit with a disproportionate amount of suffering during the pandemic—as they did pre-Covid, too. And as the world struggles to recover from the pandemic, it's a certainty that the urgent issues minorities face, such as the ones highlighted for Native Americans in this exhibit, will be pushed to the back burner.

What struck me most while looking at these photos of the Anishinaabe people—from the Great Lakes region and stretching through the upper and far West of North America—was how they were routinely offered incentives from the government but always in the form of unequal treaties that were then torn up almost as quickly as they were written. Grift is written into the core of America's creation, and exploiting indigenous peoples, slaves, and immigrants helped build this nation. Yes, great ideas about equality were written down in America's Constitution, but they were rarely acted upon for those who weren't white men in the ruling class. As Europeans entrenched themselves in North America, Native Americans increasingly lived under feudalism and saw their lands divided into fiefdoms as the various tribes were physically crushed together into smaller and smaller areas—and sometimes moved to different regions entirely—only to be exploited again and again as the federal and local governments broke promises as easily as twigs and with just as much remorse.

This precarious state of existence left some Great Lakes Native Americans from the “Three Fires” of the Anishinaabe—Ojibwe, Odawa, and Potawatomi—open to exploitation, whether it be their lands being "bought" for almost nothing, or having their photos taken against their will to show a slack-jawed nation that wanted to gorge on "otherness," which is a form of dehumanization when those people aren't thought of as equals but rather as sideshows or savages who needed to be civilized. Some Natives went along with that program, too, taking up Christianity, or willingly posing for photos in European wear—or half-Euro, half-Native outfits—while many others were forced into this situation, such as groups of Indian children being rounded up and sent to boarding schools.

“No, not even for a picture” is broken up into seven primary sections: Land & Sovereignty, Struck in a Pose, Myth Making, Complex Nationalism, Views of Assimilation, Displaced Portraiture, Daily Life. Some of the photos are in the form of postcards that have descriptive text on the back, and other images are accompanied by writings that originally appeared with the pictures. In virtually every case, there's some kind of moralizing, some kind of othering, some kind of deception in the text—or in the case of the photo that gives the exhibit its name, outright deceit. Photographer John Wentworth Sanborn convinced a reluctant Native man to stand at a corn-pounding machine—women's work then—by promising not to publish the picture. Of course, the photo was published in 1891's The International Annual of The Photographic Bulletin under the article title "Photography Among the Seneca Indians." Sanborn's prose about the circumstances of photographing this adult man uses the same tone modern parents might use when talking about coaxing their reluctant children to pose for social-media bullshit. It's the textual equivalent of a pat on the head to the kid while throwing a knowing wink at other parents—and it's totally insulting to a fellow human being.

One of the most affecting parts of “No, not even for a picture” doesn't feature images of Native Americans. The Displaced Portrature section begins with photos of the Prairie Band Potawatomi, who were forced to relocate from Indiana to Kansas on a two-month march that came to be known as the Potawatomi Trail of Death due to a de rigueur treaty fracture—are there any examples of the U.S. government holding up its end of the bargain with Native Americans? But the next photos in Displaced Portrature are of vacation cottages in Burt Lake, Michigan—home of the popular Camp Al-Gon-Quian summer camp. Prior to the Trail of Death march, and because forced removals were becoming more common, the Anishinaabe started buying up their own lands in the 1800s in an effort to keep the U.S. government at bay. The Ottawa and Chippewa in the Burt Lake area bought more than 300 acres and placed the ownership titles with the Michigan governor, but in 1900 a land speculator bought the grounds out from under the Anishinaabe because of unpaid taxes. On October 15 of that year, the new owner, enthusiastically assisted by the local sheriff, drove away the Anishinaabe, seized the land, and burned their homes. The land was then parcelled out for non-Natives to buy and build on, which is one reason why the area is filled with idyllic cottages. The 1920s postcards in this exhibit show lovely little homes in a popular vacation area, all built on the charred remains of a civilization that had been driven away by European-American greed and ruthlessness.

George H. Bonnell

Cabinet photographs, ca. 1890

These two full length portraits of Chief Shopp-en-a-gon from Grayling, Michigan demonstrate how expectations of Indigenous authenticity and identity were, and still often are, based on non-Indigenous definitions. Photography helped highlight and sometimes dissolve this divide.

If you look at “No, not even for a picture” and come away with the idea that "Wow, what horrors we inflicted on people—so glad we've evolved since then," you should probably look through it again and—as you contemplate the racism and colonialist violence perpetrated against Native Americans—consider how many equivalents still exist today against minorities, poor people, and immigrants as well as the indigenous people who have lived in North American for thousands of years before European settlers arrived.

The old saying goes, "If you're not angry, you're not paying attention." And even if you are engaged politically, it's easy to get numb to all the outrageous things governments, organizations, and people are willing to inflict on our fellow citizens out of fear, loathing, and unbridled hatred. People have had four years of emotional and physical assaults by the outgoing presidential administration, but Native Americans and other minorities have suffered attacks on their race, cultures, creeds, and religions by governments of all eras of the U.S. all for the sake of money and power.

This exhibit triggered me about how what happened 100, 200, 300, 400 years ago still happens today, just in different forms, with the past four years in hyperdrive. Not that I didn't know all that already, but the exhibit shook me out of that occasional numbness our brains use as a survival mechanism, especially in 2020, because it's a fine line between being politically active in a positive manner and absolutely drowning in the atrocities so many fellow Americans face and figuring out what issues to prioritize.

“No, not even for a picture” left me seething and I need to channel that anger into action, but how? It's unreasonable to think all the land can be given back to the people who were here first, but donating to organizations doing activist work on behalf of indigenous peoples' rights is once place to start.

Another small step toward progress is acknowledging an issue exists, which is why I and the curators of “No, not even for a picture” began our online postings with acknowledgments that where we live isn't our land to claim.

Christopher Porter is a library technician and the editor of Pulp.