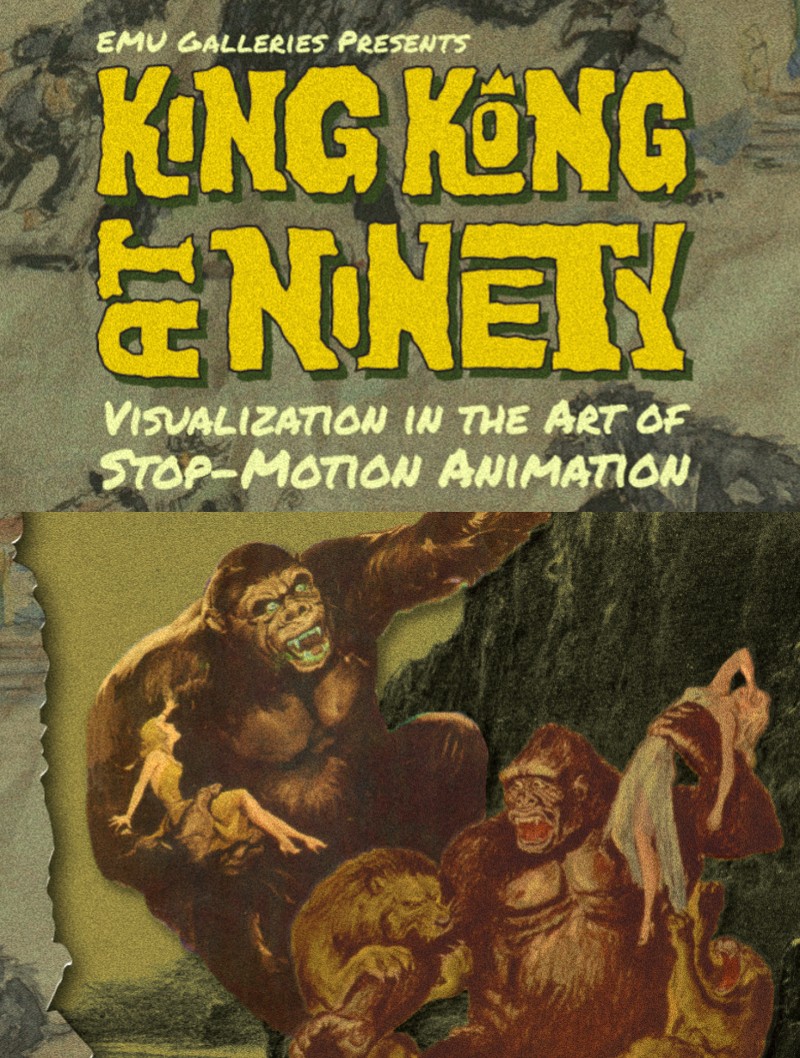

EMU's "King Kong at Ninety: Visualization in the Art of Stop-Motion Animation" celebrates the creativity behind the film that helped launch the Creature Feature

While spending an hour-plus perusing Eastern Michigan University’s exhibit King Kong at Ninety: Visualization in the Art of Stop-Motion Animation, I was struck by how, in some ways, it’s probably harder for young film buffs to stumble upon the old classics.

Admittedly, nearly all movies that survived are available to us at any moment now, but that tsunami of choices also means viewers must specifically seek out a film like King Kong (1933) instead of merely tumbling out of bed before your parents get up on a Sunday morning, turning on the TV, and sampling that week’s “Creature Feature”—a genre largely spawned by the runaway blockbuster success of King Kong.

Even so, as demonstrated by King Kong at Ninety—on display at EMU's University Gallery through February 23—theatrical rereleases of the film served this same purpose for years, offering moviegoers multiple opportunities to experience what were, at the time, cutting edge, eye-popping visual effects. (It’s interesting to note how the poster art changed with each release, as well as how it was visually marketed in other countries.)

Plus, EMU’s exhibit offers up Depression-era magazine features dedicated to revealing how these cinematic images were achieved—though more of these articles trafficked in shoddy guesswork (i.e., an actor in a gorilla suit) than in accurate, researched reporting.

But even these misinformed attempts hint at the widespread sense of wonder and curiosity inspired by King Kong. So how did this seminal movie come to be made?

Thankfully, King Kong at Ninety provides cultural context by way of media artifacts. The era’s “natural dramas”—movies pulled together by a film crew traveling to an exotic location and filming a collection of scenes—played a role, as did the popularity of films like The Lost World (1925), based on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1912 novel of the same name, and the ethnographic documentary Grass, produced by the same team that spearheaded King Kong, Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack.

But King Kong ultimately beat its chest at the box office because of its visual, stop-motion effects, and the man responsible for those was Willis O’Brien.

O’Brien’s first mainstream foray into stop-motion was The Lost World, in which a group of explorers confront a variety of prehistoric creatures; and O’Brien’s fanciful, detailed artwork looms large in EMU’s exhibit, since the success of King Kong was followed by another movie ape, Mighty Joe Young, in 1945.

The exhibit doesn’t so much emphasize the “how” of stop-motion filmmaking (other than the aforementioned magazine stories) as it does the “who”; plus, it lacks connective tissue that would more effectively pull together the whole.

For instance, concept storyboards, and art from film artists who followed in O’Brien’s wake (Ray Harryhausen, Tim Burton) are also part of the exhibit; and while I got the general sense that the work of these creatives (The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, The Clash of the Titans, The Corpse Bride) is considered part of O’Brien’s artistic legacy, I still felt as though I had to fill in a lot of informational gaps as I progressed through the exhibit.

That said, the gallery's text- and graphic-dense booklet, should you have the time to peruse it, does a more thorough job of telling the exhibit’s story.

Yet what struck me most, in the end, was a replica of the flexible stop-motion figure used in the film, poised atop the Empire State Building’s tower.

To see something the size of a toy, and know that it was made to look like a giant, terrifying monster on the big screen, is nothing less than a thrilling peek behind the curtain of classic movie magic.

Jenn McKee is a former staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News, where she primarily covered theater and film events, and also wrote general features and occasional articles on books and music.

"King Kong at Ninety: Visualization in the Art of Stop-Motion Animation" is at EMU's University Gallery, 900 Oakwood St., Ypsilanti, through February 23. There are also two special events connected to the exhibit: "An Introduction to the Archive of The Ray and Diana Harryhausen Foundation" (Feb. 7, 7 pm) and "Key speaker event for the 'King Kong At 90: Visualization in the Art of Stop Motion Animation' art exhibit with a panel of guest speakers" (Feb. 8, 7 pm).