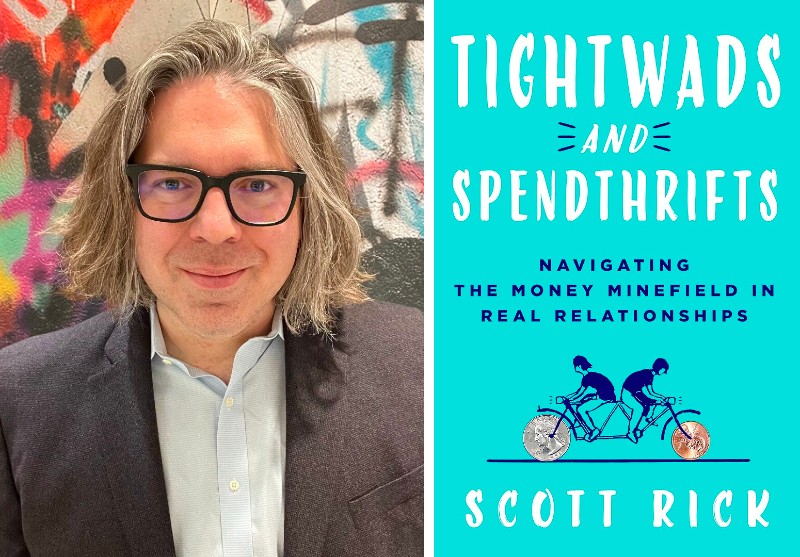

For Love and Money: U-M professor Scott Rick explores how couples navigate finances in "Tightwads and Spendthrifts"

In my family, I’m the person who insists on setting apart the cans that can be returned for deposit, while my husband says, “What do you get, three dollars? Not worth it.”

Perhaps not. But different philosophies about money, at the macro and micro level, are all-too-common in marriage. I mean, there’s a reason that finances always make the list of “things couples fight most about,” right?

To address these differences, Scott Rick, a U-M Ross School of Business marketing professor, has a new book called Tightwads and Spendthrifts: Navigating the Money Minefield in Real Relationships. Billed as distinct from conventional self-help or personal finance books, the book instead uses behavioral science as scaffolding for a broader discussion of how spending plays into our sense of personal identity; why we’re sometimes attracted to people who are quite unlike ourselves (in terms of spending); and practical ways to work through money-related conflicts.

While these arguments are sometimes about petty things (see: cans), they may nonetheless point to a much larger dissonance regarding fiscal beliefs within a relationship. As Rick notes, “Our relationship with money is complicated, no matter how much of it we have. … But even if partners would love to sidestep delicate conversations about money, the topic is unavoidable. Most of life’s major decisions—which jobs to pursue or take, where to live, how many children to try for, when to retire—are inextricably linked to money and are often made within intimate partnerships.”

As a starting point, in the book’s introduction, readers can answer a few questions to determine where they fall on the tightwad/spendthrift scale.

I scored in the “unconflicted consumer” bell curve middle, as did my partner, suggesting we’re generally on the same page financially (cans notwithstanding). Even so, given the occasional disagreements that we do have about money, I found much value and interest in Rick’s highly readable book. With its friendly, conversational tone and short length (clocking in at less than 200 pages), Tightwads and Spendthrifts makes learning about this topic breezy fun.

Structurally, Rick begins by unpacking the psychology of tightwads, many of whom experience a kind of pain when spending, and spendthrifts, who find the same act pleasurable. Rick is a self-proclaimed spendthrift, and the book, in part, is an outgrowth of his personal experience, since he’s married to a tightwad.

Though not wildly common, this “opposites attract” principle sometimes applies because both spendthrifts and tightwads often recognize that their relationship to money isn’t ideal, and are thus fascinated by those utterly unlike themselves. However, when this attraction leads to marriage, and financial choices suddenly impact a couple’s combined income— well, things get tricky, of course.

While Rick doesn’t suggest drastic adjustments, he does argue that small changes—like a spendthrift relying more on physical money, so that it’s a less abstract transaction, and a tightwad taking the opposite tack—can help, as can a joint bank account. These accounts help to erase tension surrounding income disparities between partners (Rick notes, “[I]n dual-income couples, partners belong to the same or neighboring income brackets only about 40 percent of the time”), but they also help to underscore the idea that for the couple, all money earned is “our money,” not mine and yours.

Even so, Rick acknowledges that couples ultimately have to determine what works best for them. Around 10 to 15 percent of couples maintain completely independent accounts, and Rick and his wife landed on having not just a joint account but also individual accounts they feed money into as needed so that while they know how much each person is spending, they don’t get so caught up in the details—which may be the secret sauce to fiscal harmony.

By far my favorite chapter in Tightwads concerns the less-obvious topic of gift-giving in relationships. As Rick points out, every year presents us with up to five occasions to get our partner a gift: Valentine’s Day, birthdays, Mother’s/Father’s Day, an anniversary, and the December holidays.

“Even if direct, verbal expressions of love are limited,” Rick writes, “intimate relationships still present many indirect, nonverbal opportunities for partners to reveal how they feel and what they know about each other. … Each gift we give we give our partners lets them know how ‘seen’ or understood they are.”

For this reason, Rick argues against asking a partner what they want, but if your partner verbalizes a desire without prompting, you should listen. Using himself as an example, Rick relays how he’d once observed enough about his wife to know she’d like a Kate Spade bag, but when the moment came to select one, he picked the blinged-out, pricey, impractical clutch that caught his eye, forgetting, in the moment, that his wife preferred more understated, practical pieces. “I was so excited for Julie to open this gift,” Rick writes, “but the unanimous silence it was met with still haunts me. It was just so instantly obvious that I’d laid an egg.”

This willingness on Rick’s part to share his blind spots and experiences is a significant part of what makes Tightwads and Spendthrifts such an accessible and informative read. We may all resist talking about money in relationships because, on some level, we hate meshing hard pragmatics with feelings of love; but as Rick demonstrates, if you’re building a life with someone and want the relationship to last, you’ll have no choice to face the issue again and again. Might as well have some tools for the journey.

Jenn McKee is a former staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News, where she primarily covered theater and film events, and also wrote general features and occasional articles on books and music.

Scott Rick will discuss "Tightwads and Spendthrifts" with April Baer on Thursday, January 11, at 6:30 pm at Literati Bookstore, 124 East Washington Street, Ann Arbor.