Electro-Valve Vibes: Justin Walter's "Unseen Worlds"

The warm, billowing, ambient music Justin Walter makes with the Electronic Valve Instrument (EVI) evokes Brian Eno's work the instant it caresses your ears.

But rather amazingly, Walter heard Eno's pioneering music only recently.

"That is true. So, I listened to a couple of his albums, one of which I liked a lot, Discreet Music," Walter said. "For me, it pointed to the beginnings of Boards of Canada, especially that opening number on Music Has the Right to Children. It also sounded like something I might come up with and I realized that my exploration into the world of ambient electronic music probably would have been very different had I heard this record at an earlier date. Seems like he makes amazing music."

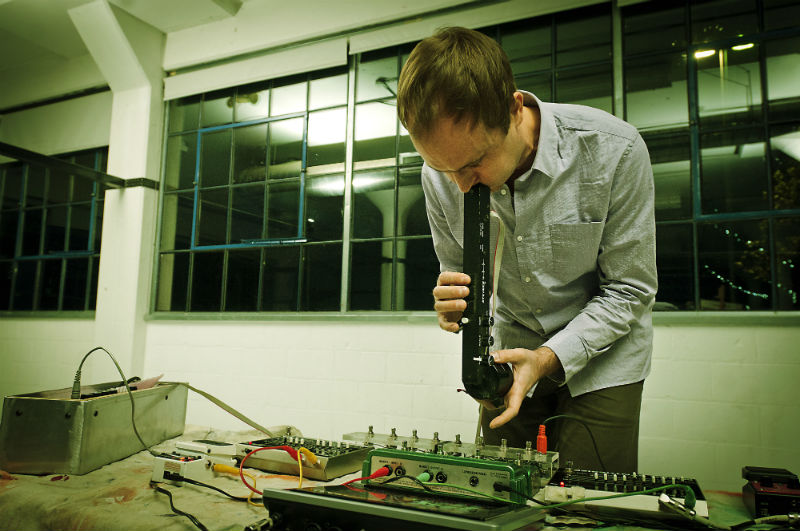

So does Walter, whether he's playing trumpet with the avant-Afro-funk collective Nomo, sitting in with Ann Arbor jazz bands, or wielding the EVI, a wind-controlled synthesizer. His first recording featuring the instrument was 2009's Music for Science Film Strips EP; 2017's Unseen Forces is his sixth. They're all gorgeous, too, featuring languid melody lines hovering over clouds of harmony.

Walter's EVI music is improvised and the songs are selections from those free recordings, which are edited and treated in the studio. "I like to use the unique structure of the instrument to explore how a melody can be created using intuition," Walter said, "which is to say that most of the time I really have no idea what I'm doing."

Well, it sure sounds like he knows what he's doing and we wanted to find out more, so we talked to Walter about improvisation, the influence of trumpeter Louis Smith, and all things EVI.

Q: I've seen you listed as being Ann Arbor-based, Chicago-based, and Brooklyn-based. Where are you living now?

A: I do live in Ann Arbor. I was living in Brooklyn for a number of years, but it's just way too expensive to be out there to have the time to work on music the way I'd like. I lived in Chicago for two weeks once. A few years ago I was going there all the time to perform and I do have a lot of friends that are musicians that live in Chicago. Also, the record label I'm on, kranky, is based out of Chicago, so it's probably a combination of those things.

Q: If the new album is like the last one, you improvised the song titles -- using the first word that popped into your head -- as well as the songs. Is the emphasis on improv related to your jazz training, or is pure improv just the nature of how you like to work with the EVI?

A: It's a bit of both. The things I find most interesting about the EVI usually occur through improvisation. And although it is true that it's almost always the first take that works out best, that's just the first take of whatever worked out. Most of what I experiment with ends up just being part of the process and is left alone [and isn't used].

Q: Have you ever written a piece for the EVI? And do you ever compose anymore a la the Stars or A Call to Arms LPs, or you do primarily work in improv settings now?

A: I don't write out music for the EVI, but when a melody comes to mind I will follow that through, so it's more of a combination of musical intent being mashed up with the unique playing nature of the instrument. What I do, though, is take the recordings and mix, edit, and sequence them. That process resembles composition.

Q: When you perform live, is it entirely improvised, or do you go back to themes from the albums and build the performances around those riffs and melodies?

A: Oh, man. When I first started out I did one show at Zebulon in Brooklyn where I attempted to do a totally live set. It was one of the most painful experiences of my life. So, yes, I do my best to re-create the works I put out. In a way, once I finish a piece it becomes a song to me and I try to do that song justice on stage. There is, of course, plenty of room for ebb and flow.

Q: With the previous album, you said, "In recent years I’ve come to see the trumpet as an instrument that speaks in slow and long sounds ...." The first thing that brought to mind was Pauline Oliveros' "Deep Listening" philosophy as well as the circular breathing of saxophonists John Coltrane or Rahsaan Roland Kirk, which is a less common technique on trumpet. Did any of these folks, or these techniques, influence you to start seeing the trumpet as one that speaks "slow and long"?

A: Not at all. This music is about expansive textures, simple harmonies, and a melody that can either speak with or add contrast to those textures. The trumpet has been explored by many virtuosos and in no way am I thinking I can add to that legacy. Instead, I use what I have, which is a nice tone and treat it as more of a layer of sound. When I do end up playing more melodically I try to play intuitively and by ear, leaving the standard jazz language behind as a base for simple commentary. The EVI, however, allows me to play strong and angular melodies that for me are new and colorful, so in addition to using it as a simple melodic instrument and tool for creating layered soundscapes, I use it as a means to convey a voice that sits above the ambiance. And hopefully, a voice that adds to the conversation.

Q: I know you studied with Ann Arbor trumpeter Louis Smith, who died last year. How did studying with a straight-ahead bebopper help you as a trumpeter even though you've said you tried and "failed" to play like Miles Davis and Freddie Hubbard?

A: Well, I think my point in saying that I had tried and failed was really to say that I now just play with my own voice, which has parts of all those guys in it. It's silly to try and play like somebody else for too long. My relationship with Louis Smith was fairly special. He gave me my first cornet in fifth grade, was my middle school band instructor, and periodically popped into my life throughout high school. At that point, I wouldn't say he had had a large influence on me, as most of my live influence was coming from trumpeter Paul Finkbeiner. Paul led the weekly jam session in town and it was the regular late nights listening to his playing that had been shaping me throughout high school.

But when I got to school in Toronto, I sat down with one of Louis Smith's records and just totally fell in love. At the time I didn't really have a working vocabulary that moved from song to song and so I spent the entire year with his music and in particular his album Ballads for Lulu. When I came home that summer I met up with him at his house and we had a blast hanging out and playing and I got to pick his head about all of the (musical) language I had been stealing from him. I think he liked that. So basically, Louis was the first guy I really grabbed a solid chunk of language from. Once you have that it's much easier to do the next guy and so on. Miles has always been the guy that speaks to me the most, and in learning the musical vocabulary of Louis Smith, I had a foundation on which I could gain perspective into what Miles and everybody else was doing.

Q: Would you go into what makes the EVI unique and why you like working with it so much? I read your explanation about being able to play around in 4ths, 5ths, and octaves and not lose the tune's original theme and was wondering if you could explain that a bit more.

A: The EVI is an analog synthesizer. It has a controller that you hold and perform with, and that controller behaves in many ways like a trumpet. It has three buttons and the synth can be set up to react to the amount of pressure you apply with your breath, sort of like a wah-wah pedal. I'm not into that wah-wah stuff. There is a canister that you operate with your left hand that controls which octave you are playing in and a button on the canister that divides the octave in half, so no button gets you a C and a pushed button gets you a G. Same thing for B/F#, Bb/F, A/E and so on. The controller has a 7-octave range. Those 7 octaves are moved up or down on the actual synth, so if set low you can play subsonic and if set high you can get into dog-whistle range. Probably best to keep it in the middle.

It takes no effort at all to produce a sound; it's just a sensor detecting air pressure. So, once you get the fingerings down with your right hand, which happen to be the same in every octave, and you get accustomed to moving the canister around and pushing the button with your left hand, the two hands can operate independently. So like if a trumpet player could somehow play a melody and move it around 7 octaves with no effort at all and always be perfectly in tune. And you can do that really, really, really fast. So you can imagine the first experiments of this. Fairly ridiculous and not really worth sharing with people. But once developed and honed, the subtle gestures and unique intervallic movement suddenly become very, very interesting and often beautiful. If I record something I find interesting and want to add it to my vocabulary, I'll work backward and teach myself how to play it from the recording.

Q: Any Ann Arbor or Michigan shows coming up?

A: No solo shows set up for Ann Arbor at this date. I'll be heading out east next month to start a run of shows with Colin Stetson. And in the distant future, I'll be with Colin Stetson's Sorrow Ensemble. We are a 12-piece band that performs an interpretation of "Symphony No. 3" by Gorecki. Everyone must come; it's an amazing piece of music. That will take place April 14, 2018, at the Michigan Theater as part of the UMS series.

Nomo has been on a fairly long break here, but we are still performing and working on a new record. We'll be doing a Sonic Lunch in July, so look out for that. There's a ton of amazing live jazz here in Ann Arbor and I'm often performing in town as a jazz trumpeter. Most notably at Rush Street from 8-10 pm on Friday nights with Dan Bennett's group (Legendary Wings), and on Sundays from 5-8 pm at the Zal Gaz Grotto with P.O.R.K (Phil Ogilve's Rhythm Kings).

Christopher Porter is a library technician and editor of Pulp.

Visit Justin Walter's Bandcamp page to buy the "Unseen Forces" LP, CD, or MP3s and his webpage to keep up on concerts.