The Evil That Men Do: Alice Bolin’s "Dead Girls: Essays on Surviving an American Obsession"

Without a doubt, Laura Palmer’s corpse remains one of the most enduring images to come out of ‘90s television.

Anyone who has watched the Twin Peaks premiere (either at the time of its airing or as part of the younger, revivalist crowd) is certain to recall the eerie impression that Laura is simply sleeping, bound to wake up any minute -- this despite, of course, the fact that she is quite clearly “dead, wrapped in plastic.”

The shot is memorable, perhaps, not so much because of any particular aspect of the composition, but because of the horrible incongruity of its visual and dramatic elements. The viewer is presented with a face apparently at peace, the only hints of death’s presence being the pallor of Laura’s flesh and the slight blue tint of her lips. Faraway from the brutality of Laura’s murder, the image is at such a great remove from the horrific violence behind it that it sits with us in a way that is particularly uncomfortable. But more than that, the image is important for its symbolic significance, for what its very presence on our TV screens says about the way we think and the stories we tell ourselves as a society.

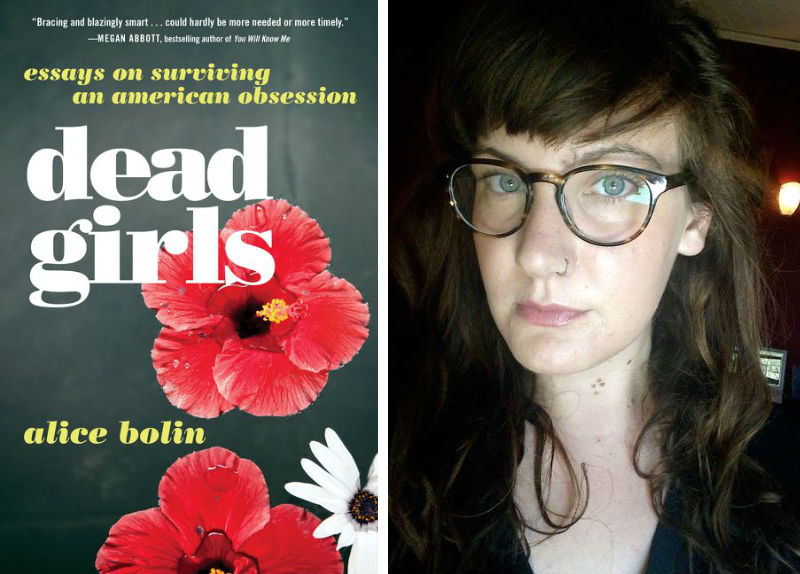

Alice Bolin takes the idea of this symbolic significance as her jumping-off point in a remarkable new collection of essays -- aptly titled Dead Girls -- which she read from on August 17 at Literati Bookstore. A sprawling mosaic of analysis, cultural criticism, and memoir, Bolin’s collection touches on much more than the phenomenon of the “Dead Girl” in the American popular imagination, despite its title.

Divided into four parts, the book's 14 essays are grouped together thematically around the ideas of “The Dead Girl Show,” being “Lost in Los Angeles,” “Weird Sisters,” and “A Sentimental Education.” As each successive section passes, the central theme becomes more and more diffuse, but the idea of this “American obsession” (as the subtitle puts it) remains lurking beneath the surface, an undercurrent running through the individual essays.

Bolin begins with the most pronounced statement of her thesis in the first essay, “Toward a Theory of a Dead Girl Show.” In it, she holds up Twin Peaks as the ne plus ultra of the “Dead Girl Show,” a wellspring that has led to a number of popular descendants, among which Bolin counts “Veronica Mars, The Killing, Pretty Little Liars, Top of the Lake, True Detective, How to Get Away With Murder, and The Night Of.”

Using David Lynch’s off-kilter murder mystery as a springboard before diving into True Detective, Bolin interrogates the ways that, for an entire genre of highly successful television, women are treated as essentially narrative props, tools by which men advance the story. As she notes, “for the detectives in True Detective and Twin Peaks, the victim’s body is a neutral arena on which to work out male problems.” And certainly, it’s FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper who is the protagonist of Twin Peaks, aided in his quest as a classic detective sage by Sheriff Harry S. Truman -- Laura herself is present only as an idea, a “sacrifice… to the most unholy idol of narrative.” To put it another way, “the Dead Girl is not a ‘character’ in the show, but the memory of her is.” Bolin’s concept is compelling, and one that transfers between shows with an adaptability and resilience that speaks volumes.

But Bolin’s engagement with the Dead Girl trope goes beyond that, and questions how the psychology of our society, how the stories we tell ourselves, shape the way that men and women interact. Particularly in an era where we have seen what seems like an interminable increase in instances of irrational (male perpetrated) mass violence and the greater visibility of niche online communities of sexually frustrated and angry men (think “incels”), Bolin’s insight into the violence men do against women is valuable. It’s not a coincidence that so many examples of the Dead Girl genre feature sexual violence against the female victims. And it’s also no secret that a lot of those who practice sexual violence, or violence born of a sexually frustrated and misogynistic place, view themselves as being essentially victims. As Bolin writes in her introduction:

One commonality of domestic abusers and mass killers is a sense of grievance, ‘a belief that someone, somewhere, had wronged them in a way that merited a violent response,’ as Amanda Taub wrote in The New York Times after the Pulse nightclub shooting. Violent men’s grievances are born out of a conviction of their personal righteousness and innocence: they are never the instigators; they are only righting what has been done to them.

In the essay she read at Literati, “The Husband Did It,” Bolin extends this critique to include even non-violent men swept up in this culture of perceived victimhood at the hands of women. Describing the character of Nick in Gone Girl, who is framed for his wife’s disappearance by (you guessed it) his wife, Amy, Bolin argues that the misogynistic Nick is ultimately less sympathetic than the devious Amy because “Amy bears no resemblance to any person who has ever walked the planet, but she bears a resemblance to women as conceived of in the nightmares of men like Nick, and there are many of those men walking the planet.” More than that, Nick is emblematic of the culture of perceived victimhood among men because “he blames [his misogyny] on being raised by his [misogynistic] father and thinks his self-awareness will absolve him. He is the classic male victim” because, in his view, “even his misogyny is something that was done to him.”

In the second season of Twin Peaks, after the demonic spirit Bob is revealed as Laura Palmer’s rapist and murderer, FBI agent Albert Rosenfield questions Bob’s existence, suggesting that “maybe that’s all Bob is: The evil that men do.” Throughout the course of Dead Girls, Bolin intermittently suggests potential alternative titles for the book as a whole. One could do worse than to suggest the candidacy of “The Evil That Men Do” for that slot, and at its heart, much of this book is really about that.

But it’s about far more than that, as the collection also demonstrates a distinctive feel for place. In a later essay, “Black Hole,” Bolin looks at length at the Inland Northwest, at the myths surrounding it, at the odd number of serial killers that historically seemed to dwell in its woods. She makes one wonder if it’s not a coincidence that a show like Twin Peaks plays out in a setting which she elsewhere describes as being portrayed, in popular media, as a place that “makes people go nuts, or, less superstitiously, [a place] where white men with chips on their shoulders feel they belong.”

But the principal place in these essays is, by far, Los Angeles. As the collection moves forward, more and more autobiographical elements start to be included. Bolin moved to L.A. in her mid-20s, and like so many writers before her, she (self-awarely) wrote about the experience of transitioning from her old life to that of the hustling-bustling city, falling into what she terms the “Hello to All That” trope. Because it’s about movement and change, and because it’s about California, it’s inevitable that the work of Joan Didion comes to mind, a fact of which Bolin is quite aware.

Particularly in her essays about L.A., Bolin self-consciously steers away from Didion pastiche while remaining open about her influences. In the post-reading talk at Literati, she described how part of the process of writing this book was learning how to give Didion up as a guiding star and become her own writer. In this respect, while it must have been challenging (seeing as, in the past, “Didion was all [Bolin] wanted to be as a writer”), and though Didion is still quite present, the author seems to have succeeded. As the reader gets further into the collection, it seems to grow more and more compelling, particularly in the places where the author engages in more explicit memoir.

Bolin’s greatest strength in these essays, ultimately, lies in her self-questioning exploration of the way she interacts with the genre, at one point even going so far as to ask, in the final, longest, essay, “how can I use the personal essay, instead of letting it use me?” By the end, she has taken on a quality that she herself ascribes to James Baldwin’s inclusion of biographical elements in his writing, which she sees as being in the spirit of “Augustinian confessions: for you to understand where [she] is coming from, [she] will tell you where [she] came from.”

Regardless, Bolin is erudite and articulate, and she covers such a broad swath of material and touches on so many big ideas in Dead Girls that it’s impossible to adequately address them all here. Her interests in the collection range from the titular topic, to noir fiction, to Britney Spears, to hypochondria, to ex-boyfriends, to witchcraft, to the plane hijacking epidemic of the ‘60s and ‘70s, and much more. (Relatedly, isn’t it a peculiar coincidence that the protagonist of Twin Peaks, Dale Cooper, owes his name to Inland Northwest plane hijacker D.B. Cooper?)

But often the same ideas recur in vastly different contexts, and not always in the same way. The acts of writing and thinking often run parallel, and throughout the collection, Bolin isn’t shy about revising earlier ideas as she reconsiders them. And that’s perhaps the thing that ultimately makes the collection so compelling -- its insights are a mix of the novel and the retrospectively obvious, but always they remain flexible.

Dayton Hare is the managing editor at The Michigan Daily and is working on his BM in music composition and BA in honors English.