Systemic Pigeonholing: "Never Free to Rest" by Rashaun Rucker at U-M's LSA Gallery

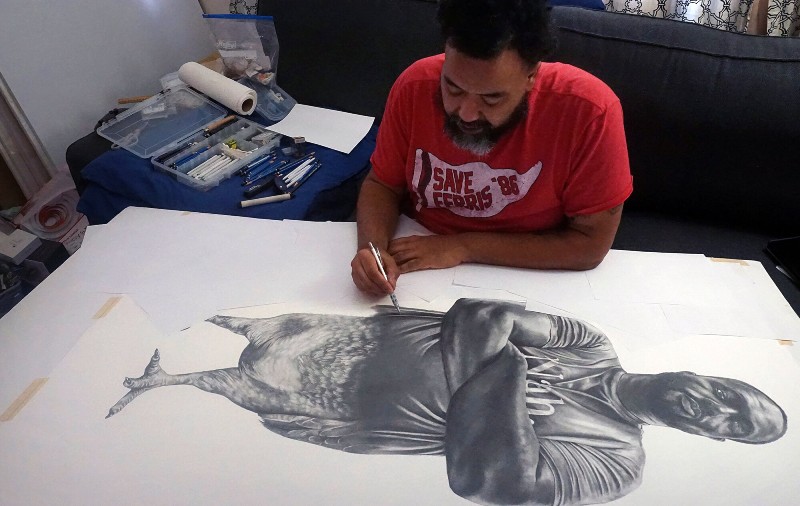

Right: The Ascent by Rashaun Rucker is part of Never Free to Rest, a new exhibition on view until Oct. 15 at the University of Michigan Institute for the Humanities Gallery.

Rashaun Rucker begins his artist statement for Never Free to Rest at U-M's Institute for the Humanities Gallery with a simple definition:

Pi.geon.hole (verb)

1. To assign to a particular category or class, especially in a manner that is too rigid or exclusive.

Synonyms: categorize, classify, label, typecast, ghettoize

In this exhibit, the Detroit-based artist examines the impact of pigeonholing Black men’s identities through a series of drawings and installations. Rucker's artist statement says he “compares the life and origins of the rock pigeon to the stereotypes and myths of the constructed identities of Black men in the United States of America.”

In the gallery space, Rucker’s installations draw out these comparisons: a small pigeon coop sits in the corner, with chicken wire, pigeon spikes, and a twisted American flag, which together evoke a prison. The constructed coop/prison, like his portraits of half-men/half-birds, is a combination of two seemingly disparate spaces used to control populations. He notes that “Black men are only permitted in certain designed or designated spaces based upon these same racial stereotypes, to occupy prisons like pigeons in coops.”

Even the pigeon spikes he purchased for the construction of the structure are marketed as “a ‘visual physical barrier’ so the birds can no longer gain access to the ledge to perch on it, moving them on to ‘more accessible areas.’” The question is: what will these new and “more accessible” areas be?

Another installation sprawls across the gallery floor: a pile of newly and intentionally broken clay shooting pigeons, each stamped with one of Rucker's portraits. The shattered clay connotes systemic violence, a system from which the only result is a pile of broken pieces. Curator Amanda Krugliak suggests that this is “a performative element of the installation process, the artist willfully breaks three times as many discs as he displays. The pieces soon accumulate on the floor like rubble. There is the sound like a shot each time a disc hits the ground with the undeniable force of gravity.” The sound echoes through the small space, reminding the visitor of the unending reality of our broken systems.

Rucker says his “practice serves as an archive of Black culture as it intersects with myths and realities.” Four of his latest composite drawings, part of his series American Ornithology, are on display in the gallery. For these chimeric portraits, he uses images of men he knows personally, or of men incarcerated by the prison industrial complex. On this topic, Rucker notes “the exhibition is influenced by the inescapable thoughts and words of friends lost: those who were incarcerated, those who believed there was no way out—that they had been permanently assigned to the bottom of America’s caste system even though their talents were immense and so often appropriated.” Those lost are represented in Rucker’s drawings as chimeric half-men, half-rock-pigeon, creating an eerie and apt visual representation of the lasting impacts of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade in American culture.

Pigeons are used in Rucker’s work as a multidimensional symbol. They are “similar to how many people see Black men in society: individuals who populate urban landscapes and live off assistance (i.e., the system) and viewed as vermin by some.” Pigeons also arrived in North America in the 1600s, coinciding with the “inception of the transatlantic slave trade in the United States.” The arrival, for pigeons, changed the concept of “home” because “within months, their location is permanently imprinted in their minds as being home.”

But human memory is not like that of the pigeon.

“Much like the pigeons," Rucker says, "Black people were taken from their place of foundation and assigned a station in society within the colonized Western Hemisphere.” In the United States, the transplanted populations expanded while continuing to face systemic oppression. The environment plays an important role in his work, as he “intends to communicate how the environment we have been placed in as Black people, created by generational systemic oppressions, becomes a reluctant contentment rather than a fleeting station.”

These threads come together to ask: How does a systemically oppressed group become free when there is an active campaign to pigeonhole them into poverty, persecution, and prison?

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

"Never Free to Rest" at U-M's Institute for the Humanities Gallery, 202 S. Thayer, through October 15. Rucker will speak on Thursday, September 30, in a virtual event as part of the ongoing Penny Stamps Speaker Series.

Related:

➥ "Detroit artist explores connections between Black men, rock pigeons in U-M exhibition" [Michigan News, September 22, 2021]