Andrea Carlson's "Future Cache" exhibit at UMMA imagines decolonized landscapes for the native peoples violently removed from their land

“Gidayaa Anishinaabewakiing / You are on Anishinaabe land”

The title of Andrea Carlson’s multidimensional installation Future Cache at the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) references the Anishinaabe storage practice of using underground caches to store supplies through the seasons.

The centerpiece of Future Cache, however, doesn't train your gaze toward the ground but up to the sky.

UMMA's Vertical Gallery has a towering 40-foot-high wall of memorial text. Written by the Burt Lake Tribal Council and presented in Anishinaabemowin (translated by Margaret Noodin and Michael Zimmerman Jr.) and English, the words commemorate the historical and ongoing effects of colonial violence on the Cheboiganing (Burt Lake) Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians.

On the lower level, a cache of Carlson's paintings complements the tower of text with imagined decolonized landscapes, as well as two carefully selected artifacts. Curator Jennifer M. Friess writes in the gallery text that Carlson aims "to draw attention to the theft of Indigenous land and to express solidarity with Indigenous communities on the long journey toward restitution.”

"Conversations on Mortality" at 22 North looks to transcend the silence about the dying side of living

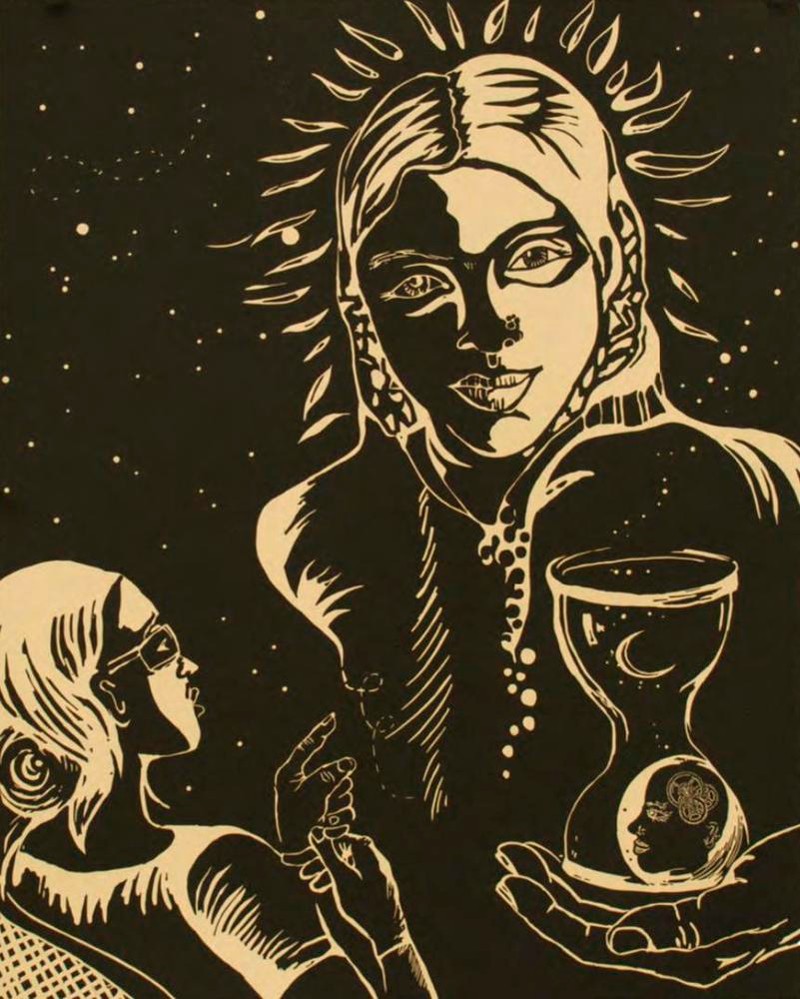

Conversations on mortality are difficult, often avoided, and in America, they are traditionally taboo. The 22 North gallery in Ypsilanti welcomes the thought-provoking exhibit Conversations on Mortality, which confronts our impermanence, the inevitability of death.

The exhibition's multimedia works engage with loss, mourning, and what is left behind once someone is gone. Described by the curators as “a chance to transcend the silence,” Conversations on Mortality offers works driven by the lives of the artists. Not only do they address the complexity of their mortality and loss of loved ones, but also their experiences of living with disability, illness, and the impact of COVID-19.

Entering the space, hanging lanterns in an autumnal palette cheerily frame serendipitously matching works by curators Sharlene Welton and Tim Tonachella. I had a chance to speak with Welton who is both the show’s curator and an artist when I visited 22 North. Welton said she created the lanterns as part of an interactive element to the opening night, where visitors were able to decorate and write their names on the lanterns before hanging them. The pieces by Welton (a large painting) and Tonachella (two photographs of cemetery views) were brought in last minute when an artist was unable to make the show, but adding the works ended up being a great aesthetic success.

Welton and Tonachella’s gallery statement notes the overlapping threads among the works, as artists grapple with the questions, “How do we embrace the changes that come from death and dying, and more importantly, how we assimilate the loss into our daily living?” Though these may, ultimately, be unanswerable questions, they are worth asking—especially when operating within a mainstream American culture that predominantly ignores them.

University of Michigan Museum of Art’s expansive "Watershed" exhibit flows through the political and social history of the Great Lakes region

University of Michigan Museum of Art’s (UMMA) Watershed exhibition comments on the complicated relationship the Great Lakes region has with water. Despite the area's broad access to fresh water, cities like Flint have endured ongoing water crises, rivers like the Huron are impacted by contaminating spills, and the Great Lakes watersheds continue to degrade.

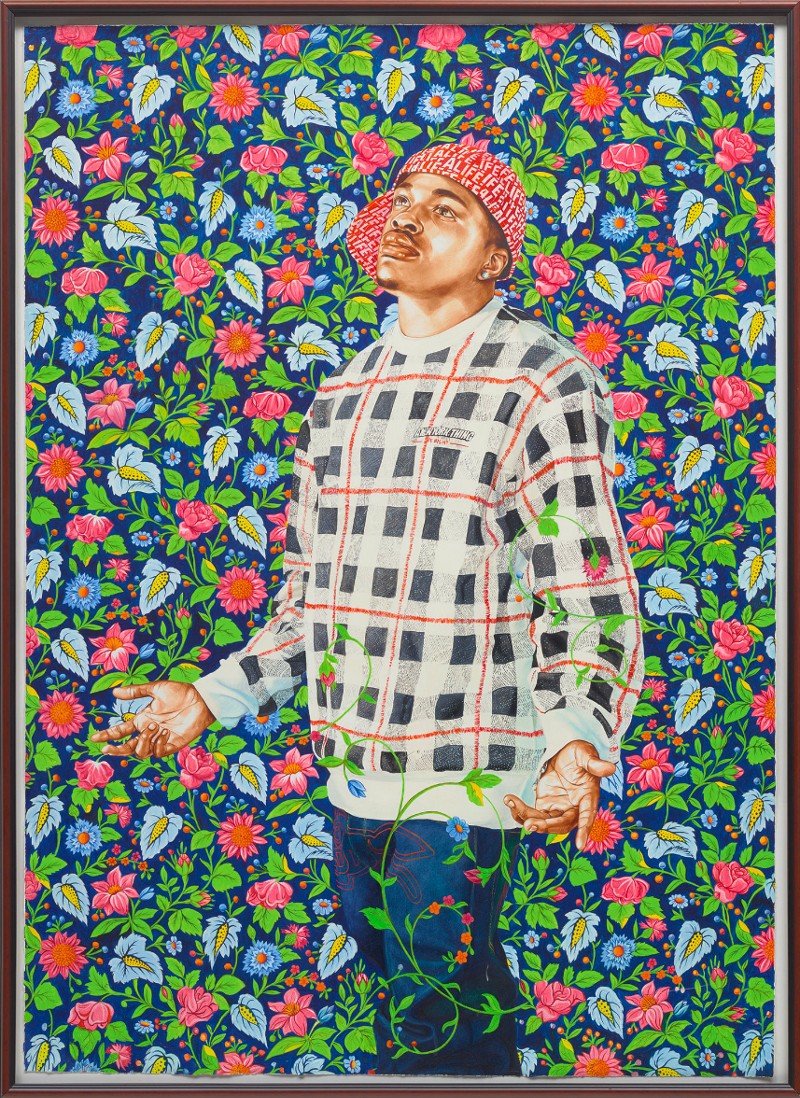

The exhibit brings together a diverse group of 15 contemporary artists whose works focus broadly on the Great Lakes area. Watershed offers wall text in both English and Anishinaabemowin (translated by Margaret Noodin and Michael Zimmerman, Jr.) in recognition of the Anishinaabeg (commonly referred to as Ojibwe) being indigenous to the Great Lakes region.

Watershed is complex and expansive. As curator Jennifer Friess states, it “immerses visitors in the interconnected histories, present lives, and imagined futures of the Great Lakes region.” The exhibition title refers to “the geographical network of the Great Lakes basin—the five lakes (Huron, Ontario, Michigan, Erie, and Superior) and rivers, streams, and reservoirs that feed into them.”

The artists’ engagement with the concept of the Great Lakes regions’ rich and often exploited resources vary in scope and content, offering a wide array of responses to past, present, and future iterations of activism and justice related to these waterways. Friess notes, “Many sound an alarm about the pervasive and lasting effects of corporate self-interest and extractive pollution. … All demonstrate how art can contribute to and shape current dialogues on the critical problems confronting our region.”

As noted, this exhibition features six new commissions from artists selected by the museum:

Systems & Shtetls: Mother Cyborg's "Crafting Our Digital Legacy" & Ruth Weisberg's "Of Memory, Time & Place" at Stamps Gallery

Stamps Gallery’s two simultaneous exhibitions have little in common visually, but they do share some overarching themes.

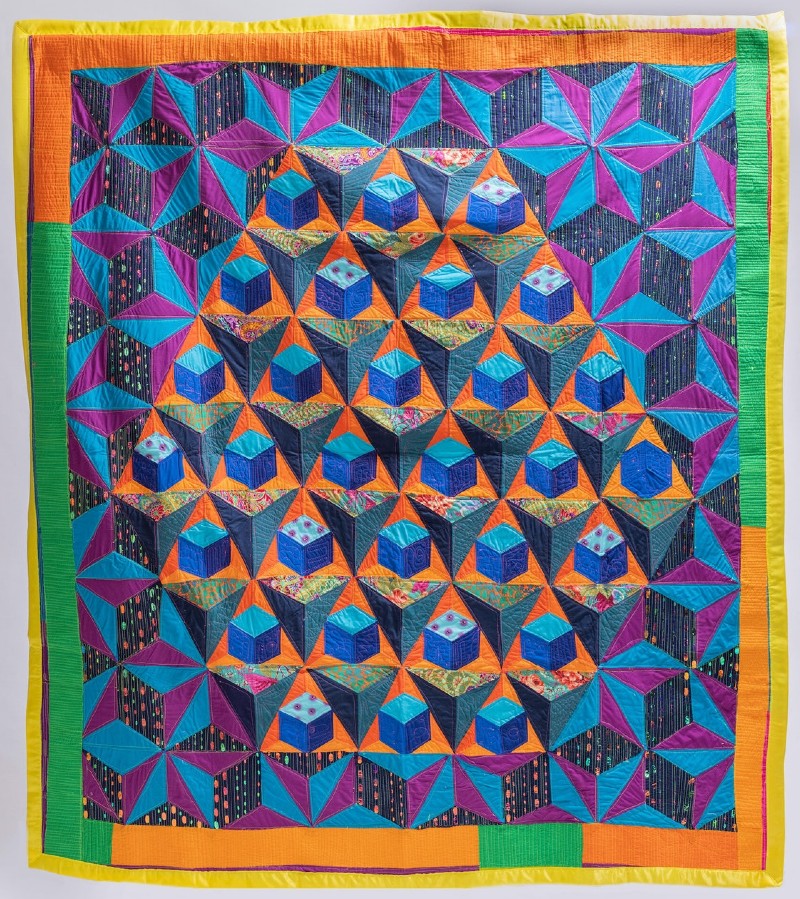

Mother Cyborg's Crafting Our Digital Legacy exhibit offers bright and captivating quilts that focus “upon our collective relationship with internet technologies, identity, legacy, and the future,” according to the text placed in the front of the gallery.

Ruth Weisberg's Of Memory, Time & Place showcases her ethereal designs and controlled color palettes in her mixed-media works.

While Weisberg’s often-muted tones and figural works contrast visually with Mother Cyborg’s dynamic abstract textiles, both artists ask us to consider where we came from and where we might be going.

You Are Invited: UMMA's "You Are Here" exhibit welcomes visitors back to the museum with works that help viewers experience the space

In March 2020, the University of Michigan Museum of Art (UMMA) was closed to the public along with countless other businesses and organizations after the announcement of a global pandemic caused by COVID-19. During that time, we were offered virtual exhibits at UMMA; then, in June 2021, in-person exhibits resumed followed by the October 2021 reopening of the museum’s classic Jonathan and Lizzie Tisch Apse, revitalized with bright, vibrant walls and artworks that interact with visitors’ senses.

UMMA’s first exhibit in the remodeled Tisch Apse is You Are Here. Curator Jennifer M. Friess writes about the joys of our renewed ability to come together in person, but she also notes that we still carry the past two and a half years with us: “While it is exciting to be together again and to see the world slowly reopen, we are also deeply impacted by what we’ve been through. This exhibition holds both of those feelings.”

Even works that have been in the space for decades seem imbued with new life.

Tracey Snelling's "How to Build a Disaster Proof House" constructions contemplate displacement and disenfranchisement

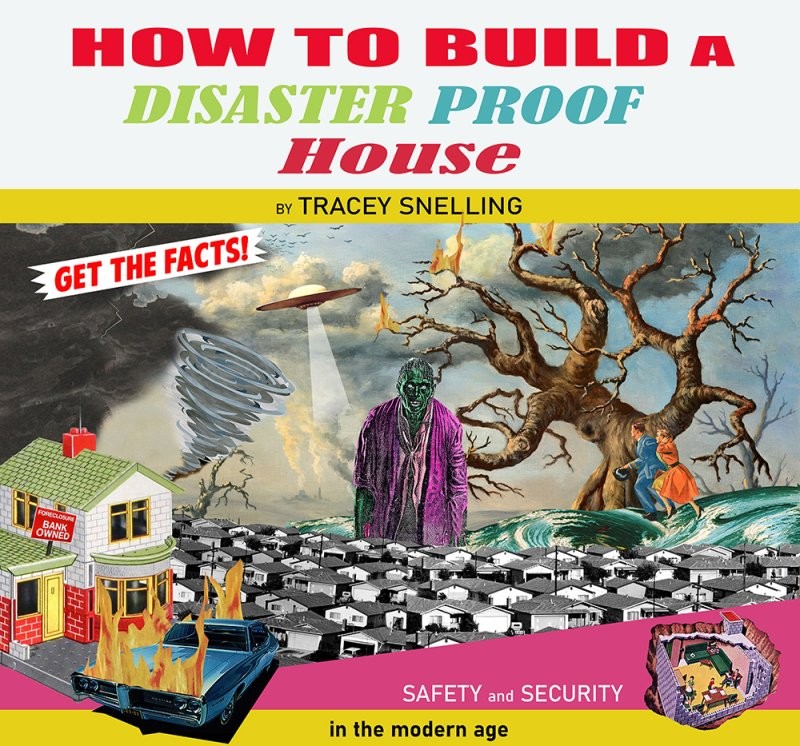

A vibrant installation at LSA’s Institute for the Humanities Gallery asks viewers to contemplate the utility (or lack thereof) of building a “disaster proof house.”

Tracey Snelling, the current Roman Witt Artist in Residence at the gallery, returns to LSA after previously exhibiting Here and There in 2017, which addressed “challenges of economic inequities, racial biases, and imposed class divisions that often limit the options available to so many people.” Her new exhibit, How to Build a Disaster Proof House, curated by LSA's Amanda Krugliak, “contemplates the uncertainty, displacement, and disenfranchisement that frames the present day” and asks, “How do we find a safe place, protected from bad weather and circumstance, in an era of floods, fires, violence, abuse and pandemics?”

Mary Sibande's "Sophie/Elsie" sculpture anchors UMMA's African art gallery

Sophie/Elsie is a striking sculptural figure, vibrant and visible from a distance, a colorful, bright beacon in the newly expanded and reopened African galleries at the University of Michigan Museum of Art.

Johannesburg-based artist Mary Sibande’s fiberglass sculpture, created in 2009, and initially on display during UMMA’s closure, is now permanently installed. In the early days of the museum’s closure, Sophie/Elsie was visible from outside the galleries—then, construction came, and she was no longer visible from outside.

But Sophie/Elsie is once again on display in the reimagined space of UMMA’s African galleries. Along with works by Jon Onye Lockard, Shani Peters, Jacob Lawrence, and many more, Sibande’s sculpture brings new life to the gallery space as part of the ongoing initiative We Write to You About Africa, in which “contemporary African artists, scholars, and curators will be asked to write about their work on postcards, in their first language, and mail them to UMMA where they will be displayed alongside their works.”

The reinstallation—including a gallery extension—is now open to visitors in the Robert and Lillian Montalto Bohlen Gallery of African art and Alfred A Taubman Gallery II.

Stamps Gallery's "Envision: The Michigan Artist Initiative" celebrates creators who are inspiring the next generation

Based on my direction of approach to the University of Michigan's Stamps Gallery, I didn’t see Michael Dixon’s large-scale sculptural alligator head with one sharp, gold tooth before entering—though it's visible in the gallery’s large front windows.

Inside the sculpture’s large open jaw, children’s toys rest as if inside a toy box. Among them, a selection of brightly colored balls, dolls, and books we might recognize from a modern store, but also amidst the display are racist toys such as a mammy doll, which remind viewers that these harmful toys are still collected and sold, holding a space in contemporary American culture that often escapes criticism.

This idea is further enforced by the inclusion of problematic Dr. Suess books, which became a topic of national conversation this past March.

Dixon is among five artists represented in Envision: The Michigan Artist Initiative, a new program focused on promoting the careers of Michigan-based artists.

This awards initiative “recognizes the creativity, rigor, and innovation of Michigan-based artists and collaboratives—and honors their role in inspiring the next generations of artists in our state.”

At Odds: "Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection" imagines a place where LGBTQ+ art can thrive

Art is often intentionally ambiguous, asking viewers to create meaning and metaphorically fill in the blanks with their interpretations.

So, then, what is queer art anyway?

(Spoiler! This exhibit will not define it for you.)

In Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection, compiled by doctoral candidate and 2019-2020 Irving Stenn Jr. curatorial fellow Sean Kramer, there is no essential “queerness” harnessed and presented in a neat package. Instead, the exhibit is framed by the words of activist, author, and professor bell hooks: “Queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

The University of Michigan Museum of Art is now fully open to the public, but Oh, Honey—UMMA's first self-described queer exhibit—went live virtually in fall 2020. Even so, the online exhibit doesn't have the same impact due to Kramer’s curatorial approach: the physicality and placement of the works affect their readings.

In this vein, it is important to note that each artwork was created by a different artist with a unique relationship to the external world; not everybody defines queerness or “queer art” in the same way.

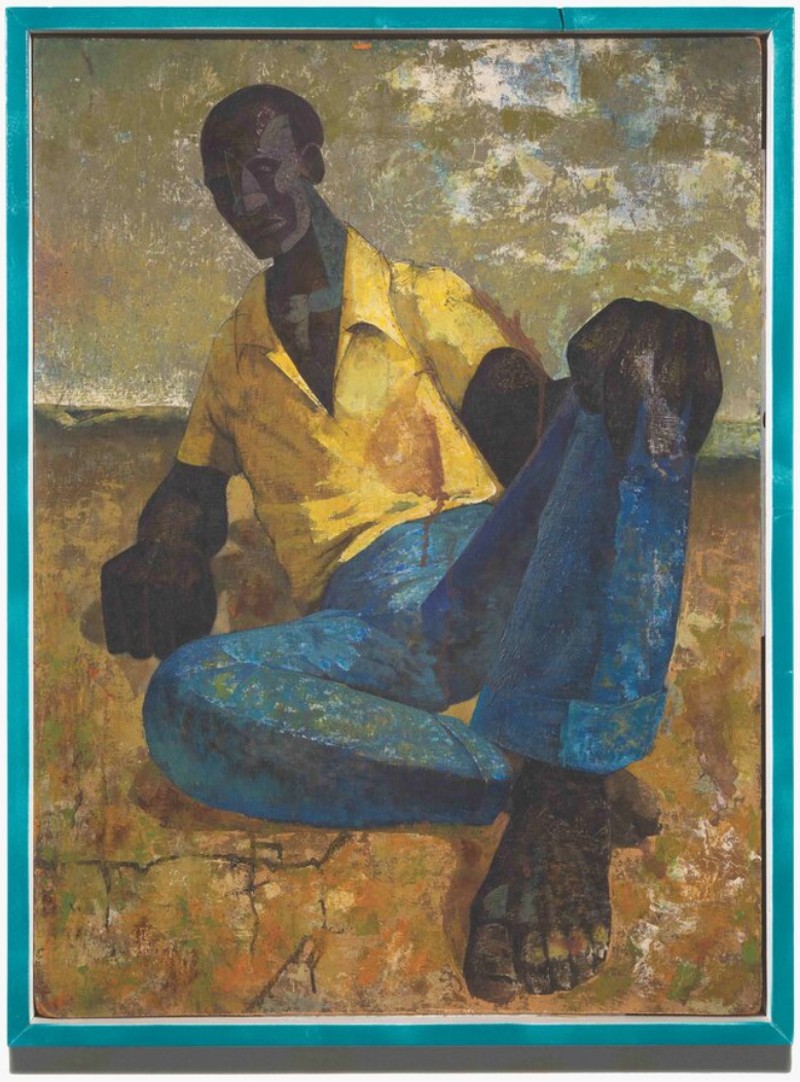

Highlighting History: "Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement"

Though Detroit is synonymous with musical innovation, the Michigan cultural center is not frequently framed as an epicenter of fine art. In a new exhibit, curators suggest that this is not because Detroit lacks—now or in the past—a vibrant art scene but because of historical oversight on the parts of art historians.

Eastern Michigan University’s University Gallery is the first place to host what will be a traveling exhibit with an in-depth look at an era, movement, and place in Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement. (You can also view the virtual exhibition here.)

The exhibit and presents a view of post-World War II African-American art history "essentially unknown to other scholars,” as the catalog states, and took 10 years to research. Julia R. Myers conducted interviews with artists, scholars, friends, and families of the featured artists, and located many works in private collections. Additionally, research was conducted by reading through numerous news sources, including the Detroit-based African-American newspaper Michigan Chronicle.