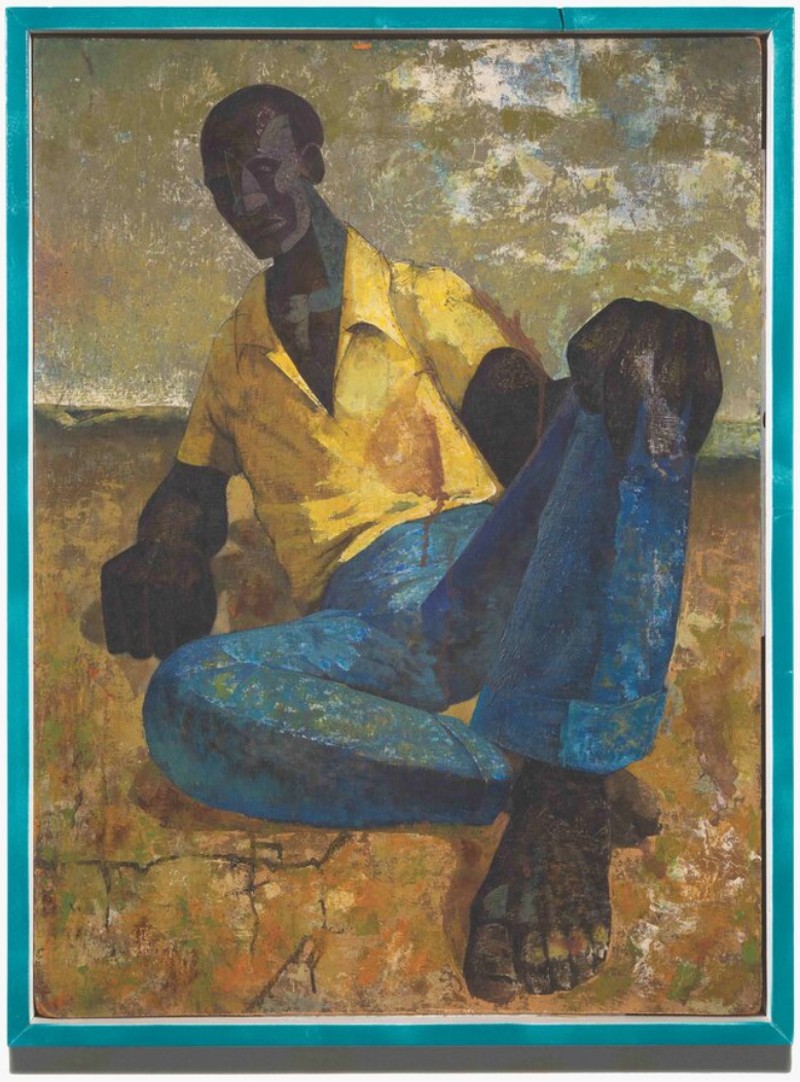

Highlighting History: "Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement"

Though Detroit is synonymous with musical innovation, the Michigan cultural center is not frequently framed as an epicenter of fine art. In a new exhibit, curators suggest that this is not because Detroit lacks—now or in the past—a vibrant art scene but because of historical oversight on the parts of art historians.

Eastern Michigan University’s University Gallery is the first place to host what will be a traveling exhibit with an in-depth look at an era, movement, and place in Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement. (You can also view the virtual exhibition here.)

The exhibit and presents a view of post-World War II African-American art history "essentially unknown to other scholars,” as the catalog states, and took 10 years to research. Julia R. Myers conducted interviews with artists, scholars, friends, and families of the featured artists, and located many works in private collections. Additionally, research was conducted by reading through numerous news sources, including the Detroit-based African-American newspaper Michigan Chronicle.

The exhibit and catalog survey the history of artists living and working in Detroit in the 1950s-1970s, but it also locates these works in relation to the larger art scene. Works by Jon Onye Lockard, born in Detroit, provide an additional link to Washtenaw County: He worked as a professor at Washtenaw Community College for 40 years while practicing art and installing murals across the country. The exhibit also compares the Detroit-based works during this timeframe to those produced in major cities and centers of art such as New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, and San Francisco, showing how Detroit artists were important contributors to African-American art. Not only are these works significant within the art scene in Detroit and across the country, but they have also left a lasting impact on working artists today.

Another goal noted by the curators of the exhibit is to address differing approaches among artists within the Black Arts Movement, described as a “rift”:

In the Detroit African American art community in the wake of the Black Power/Black Arts Movements. Neal, like other artists of the Black Arts Movement, felt that art should speak directly to the experience of African Americans using African American figurative subjects, while others artists, like Charles McGee, sought to compete in the white art world, working in the abstract, non-objective styles then dominant in New York galleries.

The curators also suggest that while many scholars have both written about and researched African-American art and the Black Arts Movement in the past 20 years, there has not yet been an in-depth discussion about the movement specifically within Detroit. The exhibit features prominent works from the Black Arts Movement, with a particular focus on the 1950s-1970s in Detroit when it was the fifth-largest city in the country and, as the curators point out, “a vibrant Black arts scene.”

Harold Neal’s works, as suggested by the title of the exhibit, are prominent throughout the space. He was a Memphis-born artist who dominated the Detroit art scene, and as the curators state, was responsible for creating “some of the most forceful artistic statements of the Civil Rights, Black Power and Black Arts Movements.”

Neal along with Hughie Lee-Smith, Glanton Dowdell, LeRoy Foster, Henri King, and Charles McGee) were educated at Detroit’s Society of Arts and Crafts (SAC), now College for Creative Studies (CCS). Unlike another Detroit institute at the time, Meinzinger Art School, SAC welcomed African-American students.

Two Detroit-based artists who influenced Neal, Hughie Lee Smith and Oliver LaGrone, also have works in this exhibit. Additionally, it features pieces influenced by Neal’s work: Glanton Dowdell, Charles McGee, Jon Onye Lockard, Henri Umbaji King, LeRoy Foster, Shirley Woodson, Aaron Ibn Pori Pitts, and Allie McGhee.

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

"Harold Neal and Detroit African American Artists: 1945 through the Black Arts Movement" will be on display at EMU's University Gallery, 900 Oakwood St., Ypsilanti, through October 20. Then it travels to the Elaine Jacobs Gallery at Wayne State University, November 4 through January 20, 2022. It continues at Saginaw Valley State University’s Marshall Fredericks Museum, February 1 to April 14, 2022. You can also view the virtual exhibition here.

Upcoming programming includes an October 12 lecture from 6-7 pm in EMU’s Halle Library Auditorium: "Detroit's Black Power Murals as Public Art" by Rebecca Zurier, who is Associate Professor in the History of Art at the University of Michigan. A closing reception and panel discussion will be held on Sunday, October 17. The reception will be from 1:30-4:30 pm, and the discussion from 4:30 to 5:30. The discussion will feature artists Allie McGhee and Shirley Woodson, both of whom exhibit work in the gallery. Dr. Samantha Noel, an Associate Professor of Art History at Wayne State University, Detroit-based artist and EMU alumni Tylonn Sawyer will also contribute to the panel.