At Odds: "Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection" imagines a place where LGBTQ+ art can thrive

Art is often intentionally ambiguous, asking viewers to create meaning and metaphorically fill in the blanks with their interpretations.

So, then, what is queer art anyway?

(Spoiler! This exhibit will not define it for you.)

In Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection, compiled by doctoral candidate and 2019-2020 Irving Stenn Jr. curatorial fellow Sean Kramer, there is no essential “queerness” harnessed and presented in a neat package. Instead, the exhibit is framed by the words of activist, author, and professor bell hooks: “Queer as being about the self that is at odds with everything around it and has to invent and create and find a place to speak and to thrive and to live.”

The University of Michigan Museum of Art is now fully open to the public, but Oh, Honey—UMMA's first self-described queer exhibit—went live virtually in fall 2020. Even so, the online exhibit doesn't have the same impact due to Kramer’s curatorial approach: the physicality and placement of the works affect their readings.

In this vein, it is important to note that each artwork was created by a different artist with a unique relationship to the external world; not everybody defines queerness or “queer art” in the same way.

In Oh, Honey, Kramer engages with a series of important questions about what is or isn't queer art while admitting there are no easy answers. His wall text states:

The truth is, I had some trouble figuring out what "queer art" is myself. ... What makes a work of art queer? Is it the sexual identity and/or gender expression of its maker? The subject matter? Who decides? To me, defining "queerness" and then assigning that definition to works of art felt like an exercise in the kind of categorizing I was trying to resist.

The exhibit is pulled entirely from UMMA’s collection, which, Kramer notes, “like many other museums, holds only a few works by LGBTQ-identifying Black, indigenous, and artists of color and none by trans artists (that I was able to find). How then could I make a show about queer artists from the collection when critical voices were omitted from it?”

The first step is to note that these exclusions have been made and strive for more acquisitions of works by a wider range of queer artists in the future.

After the first and second batch of questions posed in the gallery wall text, Kramer continues with more queries: “How does my own situated point of view, as a white, cisgender, gay/queer man/graduate student at U-M, frame my reading of UMMA’s collection? And how can I translate my encounters with the collection to you, the curious if now slightly confused visitor?”

He answers these inquiries by inviting viewers to ask their own questions and to interpret the works outside of the pieces' standard, accepted meanings:

The answers are three. First, I sought out works of art that would allow us to question categories of gender and sexuality and the power dynamics that operate within them. Second, I arranged the objects so that they could respond to, and even challenge one another. Third, I tailored the gallery texts to promote questions and thoughts rather than dictate fixed meanings, inviting you to arrive at your own interpretations.

In addition to the questioning method, the second approach in Kramer’s reading of the collection uses the juxtaposition of works to create opportunities for connections between these objects and also to notice the pieces' diversities of approach, content, and impact.

One example of the importance of context that stood out to me was the inclusion of Jeremy Penn’s MASTER, a piece I encountered for the first time in 2017—and interpreted somewhat differently at the time. I noted that the piece is part of a series and that each of the works' reflective surfaces contains an all-caps word connoting the varying power dynamics in sexual relationships. To top it all off, the collaged images that form the words are made from vintage erotica. I commented that MASTER actually seemed to be one of the "least unsettling" options among the series, which included the words “Gaze,” “Hunt,” “Lust,” “Prey,” “Power,” “Evolve,” “Beast,” and “Tease." As a small-statured, feminine-appearing person, I wondered: "Would I want to stand in front of a mirrored surface with the word “Prey” emblazoned on it and imagine myself in that space?" I approach the surface of MASTER in a "queer" exhibit and read it as a bold act of consensual defiance. Before, I interpreted this work within the context of settler-colonial and white supremacist, patriarchal histories, imagining myself and others as unwilling participants in a broad heteronormative culture.

In a recent Michigan Daily article, Cecilia Duran wrote of her experience in the gallery as “a sensorial and exciting journey.” Since she had already seen Tracey Emin’s playful, brightly lit neon sign titled Love is what you want in its permanent space at UMMA, she called it a “familiar face in a crowd full of strangers,” referring to nearby pieces that were new to her in Oh, Honey. But she also “found an underlying sequence between artworks and their meanings with regards to how they had been placed," united by Emin’s heart, which she sees as the core of the exhibit.

For me, though, the exhibit's core is Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s deeply mournful and political “Untitled” (March 5th) #2, a sculptural set of two lightbulbs designed to represent the inevitable future loss of one’s partner (created during the height of the AIDS crisis), with one life force burning out before the other.

As someone impacted by Gonzalez-Torres’s works in other museum settings, I also felt that familiar calling of an old friend—art that speaks to the issues I most deeply care about.

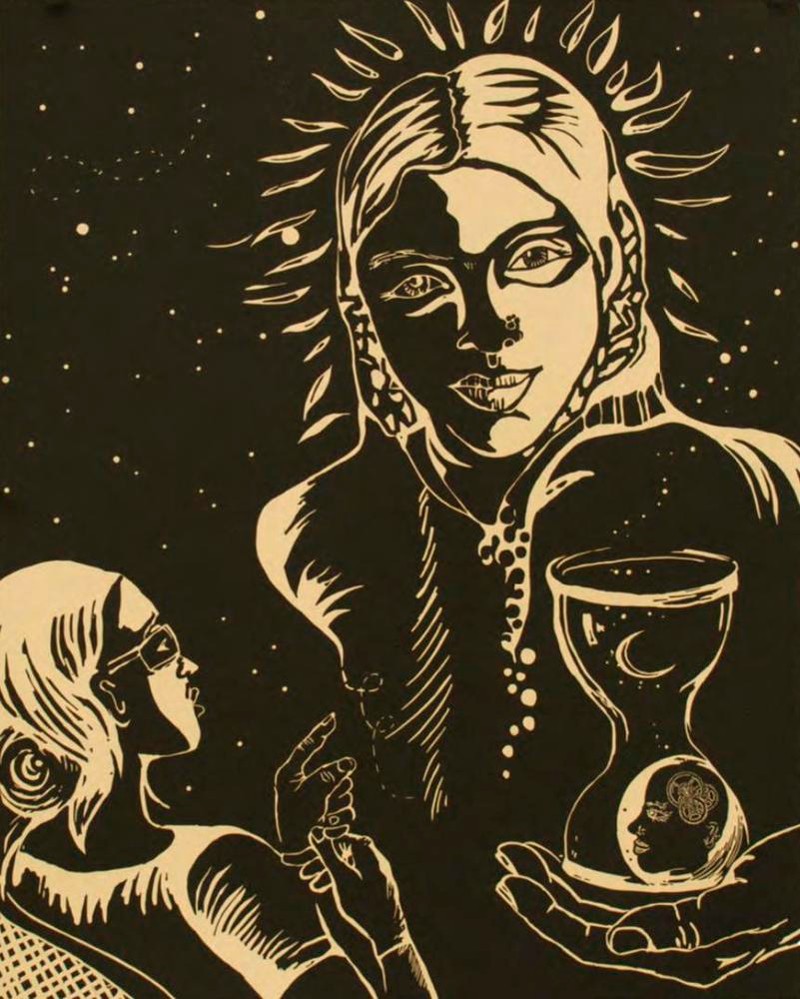

Chitra Ganesh’s 27-piece linocut print series Sultana’s Dream is a large part of Oh, Honey, filling the entirety of the left wall when entering the gallery. Her works engage with expanding concepts of gender roles historically prescribed to women. Ganesh is a Brooklyn-based artist and 2021 Doris Sloan Memorial Program virtual artist resident at UMMA. For the past 20 years, she has practiced drawings to “shed light on narrative representations of femininity, sexuality, and power typically absent from canons of literature and art.”

In Sultana’s Dream, Ganesh adapted the 1905 “feminist utopian story” of the same name by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain. UMMA’s website notes that Ganesh's work ”explores contemporary issues of societal unrest, environmental catastrophe, geopolitical conflicts, and modern hurdles to realizing utopian dreams.”

Ganesh describes the project as “a moving blueprint for an urban utopia that centers concepts such as collective knowledge production and sharing, fair governance, radical farming, scientific inquiry, safe space for refugees, and a work-life balance that includes downtime and dreaming, with women—as thinkers, leaders, rebels, and visionaries—at the helm.”

Ganesh’s project aims to create a new reality with Sultana’s Dream, and it resonates with bell hooks’ definition of queerness as a space that is made to escape the Othering world.

Kramer signs off on the gallery wall by saying, “I guess Oh, Honey… isn’t even really a queer art show. It’s more so an experiment in queering museum practice and the gallery space. It’s probably not perfect. The collection is far from perfect. But, it’s a start.”

Though the collection may not offer an inclusive or even impressive range of queer art, Oh, Honey is a good start at assessing the material UMMA has at the moment. Kramer's exhibit has succeeded in "queering" the traditional gallery space, and my hope is to see this queerification continue in an even more inclusive and radical fashion.

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

Oh, Honey ... A Queer Reading of UMMA's Collection" is at the University of Michigan Museum of Art through February 2022.

Related:

➥ In March 2020, AADL’s Jacob Gorski of The Gayest Generation podcast spoke with Sean Kramer in a recorded discussion, "What Makes a Work of Art Queer?"