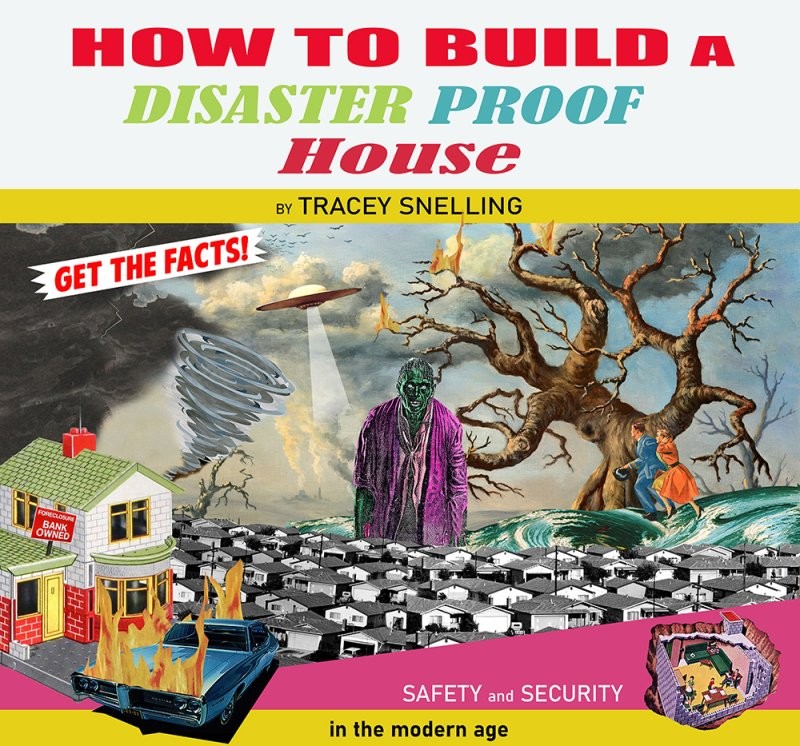

Tracey Snelling's "How to Build a Disaster Proof House" constructions contemplate displacement and disenfranchisement

A vibrant installation at LSA’s Institute for the Humanities Gallery asks viewers to contemplate the utility (or lack thereof) of building a “disaster proof house.”

Tracey Snelling, the current Roman Witt Artist in Residence at the gallery, returns to LSA after previously exhibiting Here and There in 2017, which addressed “challenges of economic inequities, racial biases, and imposed class divisions that often limit the options available to so many people.” Her new exhibit, How to Build a Disaster Proof House, curated by LSA's Amanda Krugliak, “contemplates the uncertainty, displacement, and disenfranchisement that frames the present day” and asks, “How do we find a safe place, protected from bad weather and circumstance, in an era of floods, fires, violence, abuse and pandemics?”

Inside, the shifting landscape of the kitschy interiors leaves the impression of being both a simultaneously nostalgic look at the glamorized consumerism of the past and a bleak commentary on late-stage-capitalism feelings of doom.

The installation operates as a "'laboratory,’ or open studio, where visitors can see the artist’s creative process as the installation evolves, and the rooms change, debunking any presumptive myth of permanence.” The heavily adorned and vibrant interior constructions are dizzying in their array of ephemera.

In one constructed room, a tapestry depicting a lush rainforest hangs on one of the walls. A gaudy dolphin sculpture that screams “Florida family vacation souvenir” sits on a stylized shelving system in front of it. Below the tapestry, to the right of the shelving, stands a small Keanu Reeves cut-out. A ceramic conch shell reproduction sits next to a copy of JAWS on the adjacent table.

The gallery describes the exhibit as “disarming in its exuberance, reassuring us there is no such thing as a zombie under the bed, while at the same time, making room to process the very real and unsettling world in which we live.” I experienced this “unsettling” as associations were firing off in my Millennial brain, a vast web of cultural references colliding. The sheer volume of connections I can make in this space renders them almost meaningless, reproductions removed further and further from their source material. The work seems to suggest that by seeking shelter in reproductions of beautiful, endangered landscapes and threatened species, we are living in a simulacrum—one that naively suggests humans have mastered their environments and interior worlds.

To think that the interiors I encountered may differ from those encountered by past or future visitors unsettles the idea of permanence, even in a gallery space that we know, ultimately will soon be changed again entirely to usher in a new exhibition. At the same time, the abundance of kitschy blankets, wall hangings, and trinkets in Snelling’s installations suggest that maybe the shifting tide of cultural objects would not make much of a difference to the experience—a bombardment of pop culture references and past decorating trends so saccharine they arouse suspicion.

In addition to full-scale interiors, Snelling has created small reproductions of dwellings. Visitors can approach these miniatures and peer in the windows, which prompt us to enact voyeurism with video loops running in the windows. In one window, I recognized Marlee Matlin and William Hurt converse in American Sign Language in a clip from Children of a Lesser God. In the bottom left corner window, however, a dark room with blinds pulled up playfully suggests we, the viewers, are also being watched. In a miniature mobile home, painted on top with a big “WE BUY HOUSES FOR CASH” sign, a slide show rolls on a miniature screen.

These small reconstructions were among my favorite works in the exhibit.

In her artist biography by LSA’s Humanities Gallery, curators note that Snelling’s “core skill” is that her work ”capture[s] the essence of time and place, engaging with her surroundings and merging its residents, localities, and atmospheric peculiarities.”

These rich atmospheric scenes are perfectly illustrated by her contained miniature environments, which combine sound, movement, time, and place.

Elizabeth Smith is an AADL staff member and is interested in art history and visual culture.

"How to Build a Disaster Proof House" is on view at the LSA’s Institute for the Humanities Gallery until April 29, 2022. Additionally, Snelling has a small-scale installation at Ann Arbor's Creal Microgallery titled "Portable Disaster Proof House: Take It With You!!!"; it's on display through May 15. She also has a "One Day in Michigan," a window installation at the Ann Arbor Art Center, on display through May. All the exhibits are free.