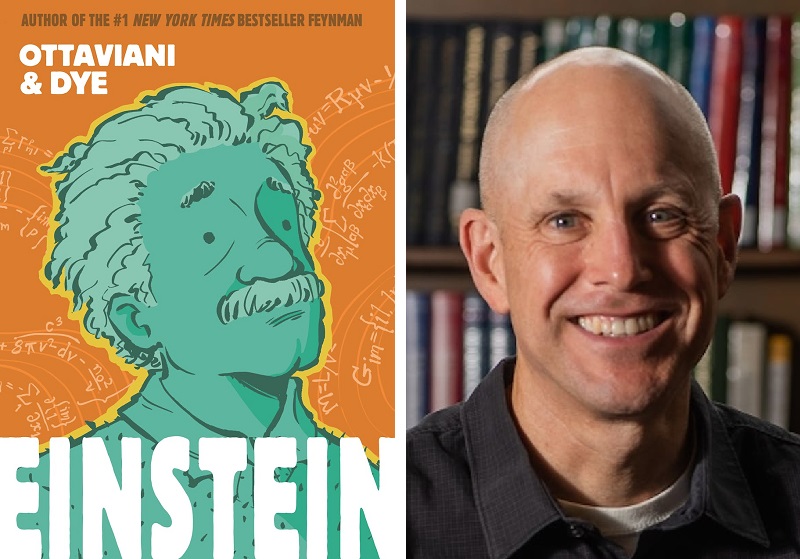

It’s All Relative: Ann Arbor Author Jim Ottaviani Examines Albert Einstein’s Complexity in “Einstein” Graphic Biography

When longtime Ann Arborite Jim Ottaviani decided to write a graphic novel about Albert Einstein with artist Jerel Dye, his first concern was doing the research and trying not to drown in it.

“Deadlines are your pal in this regard, in that, there comes a time when I just have to start writing,” said Ottaviani, author of Einstein and a former nuclear engineer and librarian who previously worked at the University of Michigan.

“I cannot put it off one more day, one more minute. Now, this doesn’t stop me from sometimes thinking, ‘I should just read this one other thing.’ But then you quickly realize there’s a hundred more things you could read, too.”

Ottaviani speaks from experience, having already published similar graphic novels focused on science giants like Stephen Hawking and Richard Feynman. The amount of content available on those icons initially gave him some pause, too, but the resulting books’ success made a convincing case for a project focused on Einstein.

“Everybody knows the name Einstein, and they know that he’s associated with relativity, but few people know why it’s important or what it is,” said Ottaviani. “The hope is that after reading this book, people will at least know what it is and why it’s important to physics. Yes, there are equations in the book, and they’re accurate, but they’re mostly there as set dressing.”

Though Ottaviani’s book primarily tells the story of Einstein’s life, he quickly determined that the physicist could not be separated from the achievements and obsessions that defined him.

“It’s OK to skim that part, but it’s got to be there,” said Ottaviani. “If not, it’s cheating both the reader who might be interested and Einstein, or Bohr, or Curie, or whomever I’m writing about. That was their life’s work.”

What do we gain by learning about the lives of the world’s greatest scientists?

“It sounds so cheesy, but what I hope comes of it is inspiration, in that these scientists all loved the process of discovery,” said Ottaviani. “… And they were all willing and able to fail, and to recognize their failures and say, ‘OK, this is not the way the world works,’ and try again.”

Ottaviani’s own “life’s work,” meanwhile, has been different things at different times. After spending his earliest years in California, and his later youth outside Chicago, he became an engineer (having first arrived in Ann Arbor as a graduate student), only to later switch gears and work in the field of library and information sciences.

Throughout these career shifts, however, Ottaviani had always been an avid reader; yet he hadn’t necessarily yearned to be a writer.

Then, in the 1990s, while sharing a meal with comics artist Steve Lieber, Ottaviani talked about the inherent drama of Danish physicist Niels Bohr meeting up with German physicist Werner Heisenberg in Copenhagen, Denmark to discuss the Nazis’ plan to build a nuclear bomb. The conversation inspired the men to tell the story in the form of a comic, which grew into Ottaviani’s first book, Two-Fisted Science.

“I’d never done anything like that before,” said Ottaviani. “I’d just written reviews of comics online. That’s about it. But then, a year and a half later, I was sitting on the floor of this guy’s living room, filling in [the black coloring] on pages for him, and we were getting ready to take it to print.”

Ottaviani’s written more than a dozen science/scientist-oriented graphic novels since, including The Imitation Game about wartime codebreaker Alan Turing and Astronauts: Women on the Final Frontier.

Yet Ottaviani initially approached Einstein with some ambivalence.

“I had never been a superfan,” said Ottaviani. “… I knew enough about [Einstein’s] personal life – his poor parenting, and his very distant relationship to most people, except for maybe Niels Bohr – to make it daunting.”

Yes, Einstein is inevitably brought down to earth in Ottaviani’s account as a neglectful, inconstant partner and parent who can’t be shaken from his intellectual fixations. But he was also an outspoken humanist, when it was dangerous to voice such views; and there’s simply no arguing his place in the pantheon of science.

“I appreciate how you can do things with comics you just can’t do with prose,” said Ottaviani.

“In the book, Einstein visually moves from being this real person, as seen through the eyes of a few, to being a cartoon character as seen through the eyes of the world. … His eyes stop having irises. His hair gets crazier and more abstract. It’s just a visual way to show the cartoony way the world came to perceive him. And once you find those kind of [storytelling] things to latch on to, all sorts of ideas come to mind.”

Plus, those of us intimidated by a 600-page prose biography of Einstein are likely to find a graphic novel more far appealing and accessible – just as the American public exuberantly embraced the genius far more than his hard-to-comprehend ideas.

In fact, as Ottaviani’s book shows, Einstein got rock-star treatment when he fled wartime Europe for America. What fueled this national frenzy?

“I don’t have an answer for that one, except to say, we really like celebrities here,” said Ottaviani. “… The country used to have a much greater appreciation for intellectual achievement than it does now. And [Einstein] was good visually. He just looked the part of a genius.”

Jenn McKee is a former staff arts reporter for The Ann Arbor News, where she primarily covered theater and film events, and also wrote general features and occasional articles on books and music.

Jim Ottaviani will discuss “Einstein” at Schuler Books, 2513 Jackson Ave. in Ann Arbor, on February 16 at 7 pm.