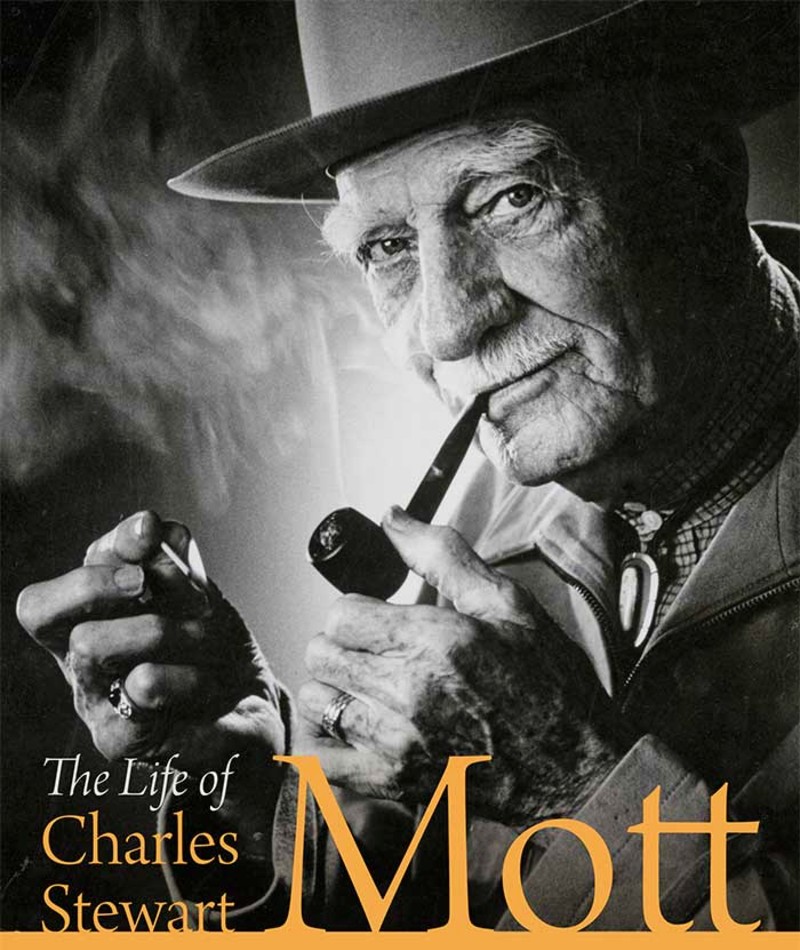

Edward Renehan's "The Life of Charles Stewart Mott" traces the life of the philanthropist and General Motors icon

Despite what Shakespeare wrote, sometimes the good that men do lives on after them -- especially when that good includes a multibillionaire family fund that continues to do charitable works decades after the founder has passed away, which is the case with Charles Stewart Mott, the subject of a new book by Edward Renehan.

A former publishing executive, Renehan has written over 20 books including historical nonfiction for children and biographies of Pete Seeger and John Burroughs. Published by University of Michigan Press, The Life of Charles Stewart Mott came about because of a query Renehan received from the Ruth Mott Foundation, the foundation started by C. S. Mott’s late wife. “[They] asked if I would be interested in doing a book on C.S., as he was known. I did some research and realized what an incredibly fascinating individual he was. This is a man who was born 10 years after Abraham Lincoln was assassinated and died two years before the founding of Microsoft.”

Mott earned a degree in mechanical engineering and “participated in the market economy and industrial expansion in a big way,” Renehan says. “He was one of the truly great innovators of the auto industry, along with his peers like Alfred Sloan, Charles Kettering, and Pierre DuPont.”

For more than six decades, Mott involved himself with General Motors. He brought his business, Weston-Mott, to Flint in 1907; when he merged it with Buick Motor Company, Mott became the first U.S. partner in the General Motors Corporation. Mott then became chief of the GM advisory staff and later served on the GM board of directors until his death. “At one point,” Renehan says. “C.S. was the largest single shareholder in GM, worth more than $300,000,000.”

Mott believed in philanthropy, forming the Charles S. Mott Foundation in 1926; ultimately, he gifted about 75% of his fortune to the foundation. But “instead of just giving the money and walking away,” Renehan says, “C.S. served as the chairman of the board and after he retired from GM, spent five days a week at his foundation offices in downtown Flint.”

The Mott family remained heavily involved after the death of its founder, with sons, grandsons, and sons-in-law stepping up to run it. Renehan says, “The foundation has grown incredibly since its founding. As of its 90th anniversary, it had given away around $3,000,000,000 in grants and still have about that amount left thanks to investments.”

Mott’s widow, Ruth Mott, started her own foundation that is focused on Flint and arranges events for kids and educational programs. The dedication to the children of Flint runs deep with the Mott Family.

“C.S. founded a camp that was just outside of Flint so that inner-city kids could get into nature,” Reneha says. “During my research, I talked to a man had gone there as a kid. After a few days though, he got homesick, so he and some friends started back for home along the road back to Flint. By chance, C.S. and Ruth had been out at the camp that day to have lunch with the kids and when they saw these boys walking, they pulled over and asked if they needed a ride. The man said that C.S. very nicely asked why they had been unhappy at camp. He took them to a drugstore for ice cream sodas, got one of his secretaries from his office, and then really listened to what the kids had to say about why they were homesick, what [Mott] could have done better with the camp. The secretary took notes, and Mott studied them later so he could make the camp better.”

Renehan posits that the things Mott and his contemporaries experienced very much mirror the technology revolution.

“From the inception of the automobile industry through the next 20 years or so, they saw the car go from a rare and expensive luxury item to something that was in every suburban middle-class driveway," he says. "A number of inventors tinkered around in their garages, trying to make their version of the car dominate so you had all of this innovation going in a relatively short period of time. Same with the dawn of the personal computer which went from the founders’ garages to something that only a handful of people owned to something that is now in every home and office.”

The long trajectory of Mott’s life is itself a story. He served in the Spanish-American War, participated on the home front of both world wars, and died during the Vietnam War. Along the way “he served as mayor of Flint twice and touched the lives of countless Flint residents, who adored him," Renehan says. "He didn’t necessarily always hang out with DuPont and Kettering -- he had friends across all social strata. There are still a number of people around the city who knew and loved him.”

Mott’s influence and generosity are still on display in the form of the Applewood Estate, his working farm that he owed until the 1940s. Visitors can tour the mansion that is run by the Ruth Mott Foundation. Thousands of students attend Mott Community College, which is built on some of the land that used to belong to the farm. Many more are served by the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital, which was built thanks to a large donation from C.S. Social and environmental issues also benefitted from the great man.

“His thinking about politics and social issues naturally evolved much in the same way that the country did," Renehan says. "C.S. was a leader in integrating the races in Flint -- his boys’ camp was the first in the area to become integrated and later it became coed. Likewise, he respected environmental impacts long before it was fashionable to do so.”

But it wasn't just Mott's philanthropy that interested Renehan. “He loved to sail and was fascinated by the American Southwest," he says. "Once a year he would take a month or so off work and go to Arizona to work on a ranch as a cowboy. He called himself ‘Desert Dick’ and worked, ate, and slept right alongside the other ranchers.”

Ultimately, both the generosity and complexity of C.S. Mott attracted Renehan to the project.

“The juggernaut of his goodwill and good works is still rolling," he says. "All that funding comes from him, from his money invested by the two foundations to keep growing and making good things happen.”

Patti F. Smith is a special education teacher and writer who lives in Ann Arbor with her husband and cat.

Edward Renehan will read from T"he Life of Charles Stewart Mott" at Literati on Tuesday, August 13 at 7 pm.