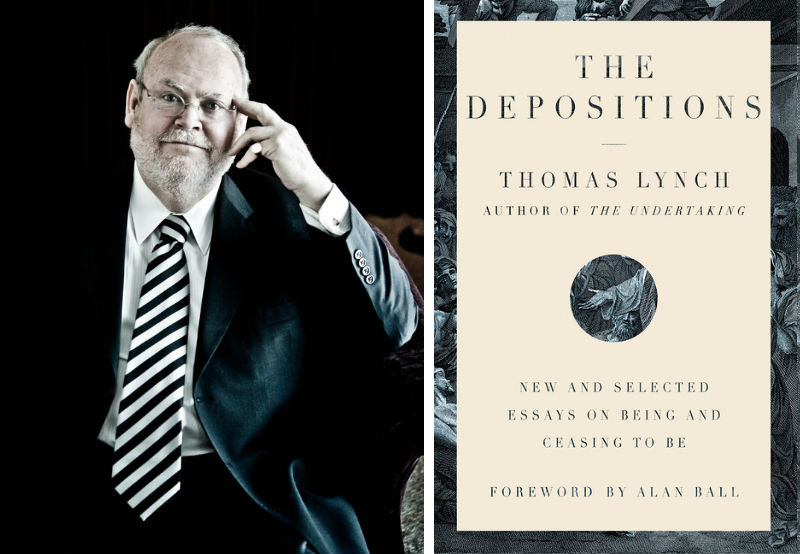

Writer, poet, and funeral director Thomas Lynch examines life and death in "The Depositions," a collection of new and selected essays

Essayist and funeral director Thomas Lynch writes, “By getting the dead where they need to go, the living get where they need to be.”

That quote forms the first sentence of “The Done Thing,” the last essay in his recent collection, The Depositions: New and Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be.

For years, Lynch has been in the business of the former and has reflected on the latter, as well as the former, through writing. He stands clear on many things about death, including that funerals serve the living and that the dead don’t care.

The Depositions: New and Selected Essays on Being and Ceasing to Be sifts through these subjects with pieces from his earlier four books of essays, plus new ones that consider the author’s state of affairs.

Lynch’s philosophical insights and candid facts about death all orbit around a universal truth appearing in the last sentence of the same paragraph containing the earlier quote:

And this is coded in our humanity: when one of our kind dies, something has to be done about it, and what that something becomes, with practice and repetition, with modifications and revisions, is the done thing by which we make our stand against this stubborn fact of life -- we die.

It is one thing to know about this reality and another thing to live with death, to sit with its certainty and consider it in relation to your own life. Lynch’s prose draws on quotes from other writers and the Bible, history and politics such as genocides, observations about places including Ireland and Michigan where he now divides his time, and personal stories about close friends, family members, fellow poets, and neighbors in the town where his funeral home is. Through these connections, Lynch’s essays treat death as matter-of-fact as you might expect from an undertaker who sees it regularly, while acknowledging the profound impact that death has on us, both our and our loved ones’ impending deaths.

Alan Ball, creator and producer of the television show Six Feet Under, found inspiration from Lynch’s essays and gave the foreword for The Depositions. He writes, “Reading Thomas’s work is to suddenly be able to see what it’s like to be comfortable with mortality. To respect it but not fear it. To see both the absurdity and the beauty of death, sometimes simultaneously.”

While talking about death often involves those big ideas -- sorrow, joy, absurdity, beauty -- Lynch examines them deeply and, in doing so, puts this inevitability into words that are not rote but rather hard-earned, lived perspectives on death.

When I first encountered Lynch’s writing, it was through a recommendation from my mother, who grew up in the same town where Lynch directs funerals: Milford, Michigan. I read his essays and poetry with the curiosity of a young person both troubled and fascinated by death. Now as I see everyone inevitably age, Lynch’s essays offer me and readers, as Ball suggests, "the necessity of being able to shrug [life and death] off while still staring it straight in the face.”

Lynch conversed with Keith Taylor and read to a standing-room-only crowd at Literati Bookstore on Monday, January 6. I interviewed him by email afterward.

Q: Tell us how you came to be both a funeral director in Milford, Michigan, and a writer.

A: I cannot remember a time when I wasn’t reading or writing, and I think the two are elements of the same enterprise. During my otherwise lackluster college years, I fell under the sway of an English professor who was committing poetry on a regular basis, and he directed me to Yeats and other Irish writers as well as the Americans -- Williams, Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Millay, and a host of others. Eventually I started committing poetry on my own. It also became clear to me that in our country poets are not paid for their efforts so most must have a day job or side hustle to keep body and soul together. Thus were the universities and writing programs invented, but I had more interest in the work I’d watched my father do as I was growing up and working at the funeral home. The care of the dead and the bereaved seemed more meaningful to me, and I admired my father’s work and how it impacted ordinary lives in extraordinary circumstances, so I decided to go into the family occupation. I just never thought it was an either/or situation, rather a both/and. I could do each with full engagement. It has worked out that way.

Q: Your new collection, The Depositions, spans many years of writing. How did you select essays for this book?

A: In fact the oldest essay in that book, the first one and title piece in The Undertaking, was written at the direction of Gordon Lish who edited my first book of poems in 1987 and asked for that essay in January of that year. So 33 years ago now. I selected, from each earlier collection of nonfiction, essays that still seemed fresh to me and rang true and added bits and pieces I’d written in the last five years in response to commissions from editors, the deaths of friends, and my own curiosities.

Q: When speaking with Keith Taylor at Literati, you discussed The Depositions title and cover image. Could you tell Pulp readers how this title and artwork were selected?

A: I wanted a title that focused some on the essay form and used “Tests and Measures” as the working title for the project. For reasons I understand, the publisher wanted something more easily marketable as something dealing with mortality and mortuary culture. We settled on The Depositions because it carries a couple of meanings: first as testimony given and written down under oath, secondly as a term of religious art having to do with the removal of Jesus from the cross and placing him in the grave which will be emptied for Easter. The removal of the body from the place of death and getting it eventually to the place of disposition -- grave, crematory, crypt, etc. -- is an essential routine of undertaking. In both cases, the meanings suited me.

The cover art, largely hidden by the cover information, is from an 18th-century engraving of an episode from the New Testament in which the paralytic is healed at Capernaum, called “The Sick With the Palsy Is Healed and His Sins Forgiven,” by James Newton in the Wellcome Collection in London. It forms the basis of the Seamus Heaney poem, “Miracle,” and involves lowering the paralyzed man through the roof to place him in a crowded room at the feet of the preacher and healer, Jesus. The three gospel accounts make clear the comparison of manifest and invisible healings of the body and the soul. I find that the questions my essays deal with more and more are these sorts of questions -- which is the greatest miracle? To forgive sins or heal paralysis?

Q: The description of The Depositions discusses how, “The press of the author’s own mortality animates the new essays, sharpening a curiosity about where we come from, where we go, and what it means.” Could you expand on the ways that your writing has changed over time, particularly in light of your new essays in this book?

A: Speaking for myself, time has focused my thoughts on finitude, time running down and out, the beckoning embrace of last things, and mortality, my own and others. Anyway, there seems an immediacy about writing now that wasn’t there when the press of time was gentler.

Q: In one of your new essays, “Introit,” you mention sharing your poems at “Joe’s Star Lounge on North Main Street in Ann Arbor.” Tell us about reading there. How did you get involved in the Ann Arbor-area literary community? When was this?

A: Sunday afternoons in the early 1980s is when I remember driving down to Ann Arbor to drink and read poems with other local poets at Joe’s Star Lounge on Main Street. The light inside was beautiful and blurry, and the sense one had was of sharing their party-pieces with fellow pilgrims who’d brought their own “dish” to pass. It was the closest thing to a community of poets I’d ever experienced. I’d published a few poems in Poetry magazine and had shared some of those pages with Alice Fulton who was on a fellowship then after the publication of her first poem, “Traveling Light.” We met for lunch, and she invited me to a workshop with herself, Richard Tillinghast, Keith Taylor, Stephen Dunning, and a couple others. It was a real gift to have such readers commenting on that early work.

Q: Also during your conversation with poet Keith Taylor, you spoke about Michigan as a great place for writers. How has the state been a good place for your writing?

A: Not only has Michigan a grand cohort of writers in all genres, it enjoys the presence of very fine universities and independent presses and a network of venues for public readings and conferences. There is a sense of fellowship among writers from different areas of the state. Also the state is benefited by a great diversity of religious and ethnic cultures which inform much of the literary and artistic projects. Of course, the natural wonders of our peninsulas contribute to a keen sense of place which undergirds our imaginative endeavors.

Q: Speaking of places, you also have a family history and home in Moveen West in Ireland, where you first went in 1970 after drawing a high draft number. This place comes up frequently in these essays, both the new and older ones. I’m always curious about how living in other places causes perspectives to shift. How have your international connections and residences influenced you, your writing, and your view of home?

A: The differences between suburban middleclass America and rural Ireland were, in 1970, considerable, so that my experience in West Clare and working in Killarney did give me insights that ring true still today, half a century later. The changes in both American and Irish cultures have narrowed the differences, but Ireland still has for me a deeper sense of place and family than the Michigan suburban experience. Part of that is that the house I occupy in Moveen is the house my great-great grandparents occupied in their marriage in the middle of the 1850s and the house my great grandfather came out of to go to Jackson, Michigan, whence he never returned. So, in a sense I am the returning Yank bearing three generations of my family, which, though connected to this parish, either never returned or never saw this place. The press of family history is real here whereas it is not so much in America.

My association with London, Scotland, and the U.K. owes to a happy history with producers from the BBC Radio, Kate McAll and later Kate Bland, both of whom have commissioned and recorded essays from me, also my editor at Jonathan Cape, the poet, Robin Robertson, as well as a long friendship with the late poets, Matthew Sweeney, Michael Donaghy, and others.

Q: You write in the introduction to Bodies in Motion and at Rest, as it is included in The Depositions:

I sleep well, rise early, and since I don’t do Tae Bo or day trading, I read or write a few hours each morning. Then I take a walk. Out there on Shank’s mare [an Irish term for walking], I think about what I’m reading or writing, which is one of the things I really like -- it’s portable. You don’t need a caddy or a designated driver or a bag full of cameras. All you need’s a little peace and quiet and the words will come to you -- your own or the other’s. Your own voice or the voice of God. Perspiration, inspiration. It feels like a gift.

This begs the question, what are you reading these days?

A: I’m in Ireland at the moment so confined to my serviceable but smallish library here. Am rereading Stepping Stones, the extensive interviews between Dennis O’Driscoll and Seamus Heaney, the bed of heaven to the two of them. They died within months of one another, and I attended both their funerals and continue to find much for reflection in their colloquies. Am also reading an anthology of poets published by Salmon Poetry and Jessie Lendennie, the founding editor of Salmon who has, for nearly 40 years, added the voices of poets, mostly women, from the west of Ireland and the U.K., Europe, and North America to the chorus of poetry in Ireland. We don’t feel the time going, but the perspective of 50 years since I first came here focuses my imprecise institutional memories. Also some Contemporary Essays published by Scribner’s in 1929 and edited by Odell Shepard. I brought it on the plane because it is a pocket-sized hardcover. Finally, I found a volume of short stories, Cathedral, by Raymond Carver in Charlie Byrnes Bookshop in Galway for six euros. I think this may be a reread for me, but they feel fresh, though written decades ago.

Q: With The Depositions, an impressive collection of years of essays, now published, what’s next for you?

A: I have four projects I’d like to devote my remaining time to: a new and selected volume of poems; a long fiction I’ve worked on for 10 years or more; a children’s book; and a book-length essay on the failure of traditional marriage as a paradigm for intimate conduct, healthy companionship, and the knowledge of another human.

Martha Stuit is a former reporter and current librarian.